- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps Jim Bibby

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Jim Bibby

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

By the end of the 1970s, the baseball card industry/hobby had become somewhat stale. The hobby needed a transfusion, which it received in the form of a major court ruling that eliminated the Topps monopoly and opened the door for two other companies (Donruss and Fleer) to enter the fray. That court decision created new streams of competition, while simultaneously prompting Topps to improve and refine its product.

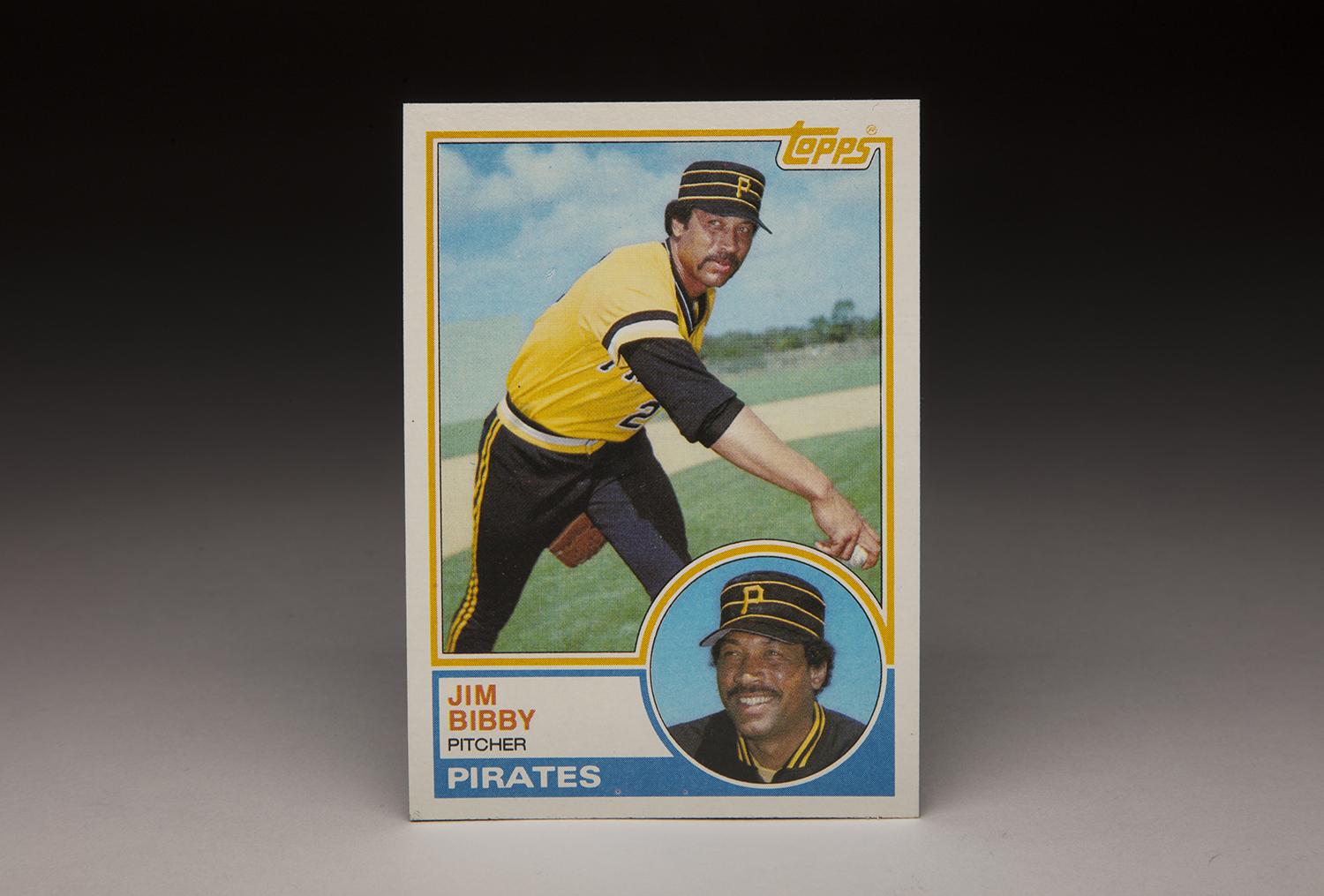

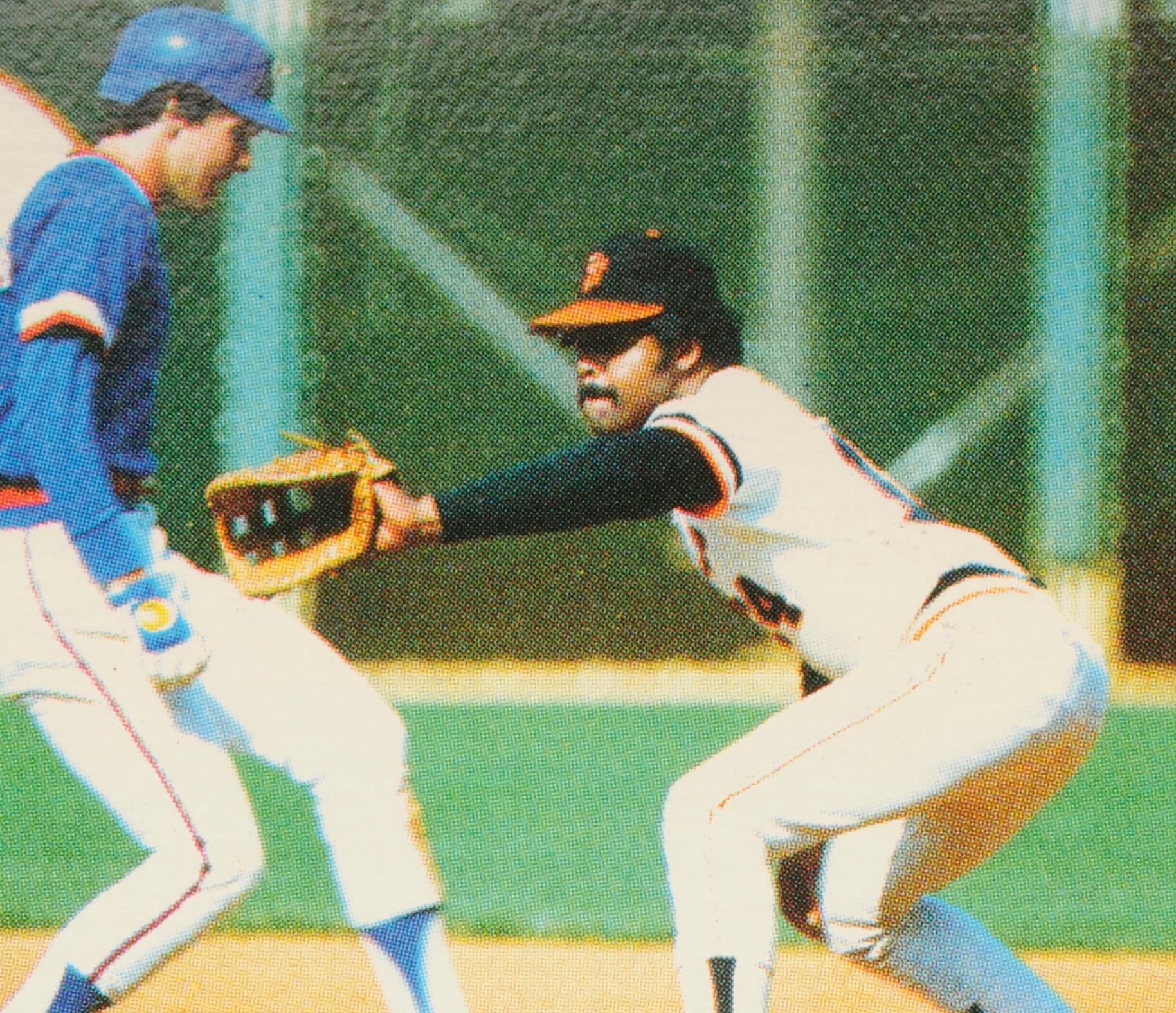

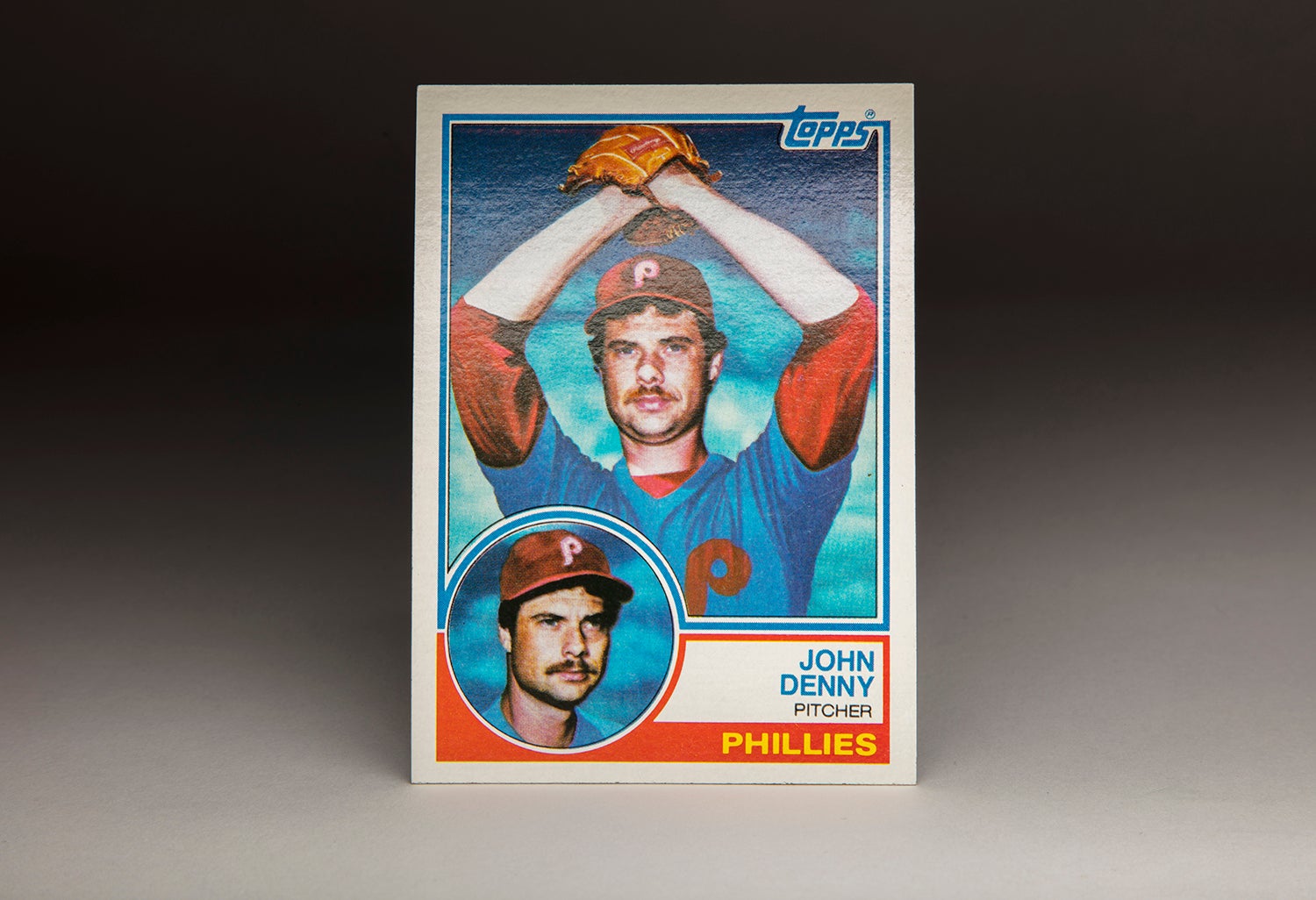

In 1983, Topps started to turn the corner with the release of a card set that would become a huge hit with collectors. For the first time since the early 1960s, the Topps cards featured two photographs: A larger, base photograph, complemented by a smaller inset photo contained in the lower corners of the card. To make matters more appealing, Topps made a majority of the base photographs action shots, satisfying the desires of many young collectors.

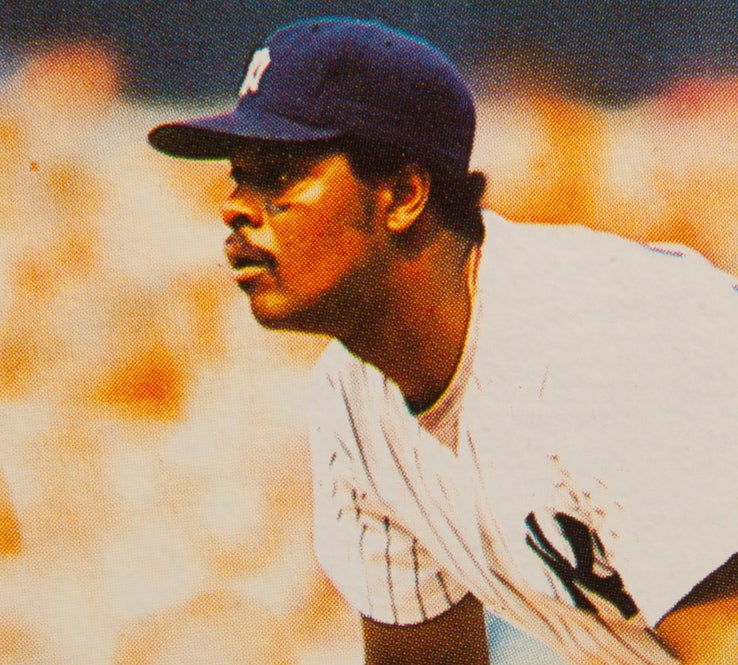

The photography on the cards also appeared much sharper than what had been produced in 1981 and ’82. The Jim Bibby card is a good example. Given the clear, crisp presentation of the main photograph, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ black and gold colors of that era, so gaudy in their brightness, practically jump off the cardboard. The sunny background, in what appears to be a picture perfect Spring Training day in Bradenton, Fla., only reinforces the boldness of the color. This is a card that cannot help but to grab your attention.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The Bibby card also presents us with a bit of artistic license. In feigning a practice pitch (notice how Bibby continues to hold onto the ball even at the finish of his follow-through), he appears upright while the Spring Training landscape behind him looks to be tilted. In reality, it is Bibby who should appear to be bending over more appreciably as he completes his practice pitch, and it is the field that should be flat and even. Whether intended or not, it’s a nice piece of photo trickery that gives the card an offbeat twist.

As a player, Bibby was best known for a few matters of note: Being the brother of NBA shooting guard Henry Bibby, authoring the first no-hitter in the history of the Texas Rangers in 1973, and pitching for a world championship team in 1979. Those are all notable facts, but they only begin to scratch the surface of a memorable player who was also a war veteran, a positive character in the clubhouse and an underrated pitcher for many years.

I’ll also remember Bibby for relatively trivial reasons. He was one of the biggest pitchers of the era, a hulking 6-foot-5, who pushed the scales to the 250-pound mark. In today’s game, such dimensions are more common, but in the 1970s, few pitchers had that kind of a massive frame. Bibby also perspired more than any other player I’ve ever seen. On hot and humid days, he would look like comic actor Albert Brooks in the wonderful 1980s film, Broadcast News. Remember the scene where Brooks auditioned to read the news? Overcome with nervousness, Brooks’ character perspired so much that the producers had to change his shirt in the middle of the newscast. Bibby was similar. He sweated so much on the mound that it was hard to watch him work; the more you watched him, the more that you started to sweat.

Perhaps my most profound memories of Bibby come from the riotous book, Seasons in Hell, an account of the Texas Rangers of the 1970s written by Mike Shropshire. According to Shropshire, Bibby used to go by the “stage name” of “Fontay O’Rooney.” (I’m not exactly sure what “stage” Bibby was appearing on, but that’s a question for another day.) And no one understood why he picked the odd moniker of Fontay O’Rooney. The alter ego just made him more colorful, a man whose friendly, amicable personality belied his intimidating physical appearance. Teammates enjoyed being around Bibby in St. Louis, Texas, Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

As good-natured as Bibby was, his road to the major leagues was not easy. He was signed by the New York Mets in 1965, but his career was interrupted by both a back injury and military service in the Vietnam War. After his first year of professional ball, in which he pitched poorly, he was drafted by the U.S. Army and put into service in Vietnam, where he drove supply trucks. That was particularly dangerous duty during wartime, but Bibby escaped the assignment without injury or incident.

Later in his career, Bibby downplayed the level of danger. “We handled everything from dead bodies to plastic trucks,” Bibby told Murray Chass of The New York Times in recalling his work as a truck driver. “My unit never got hit, and I didn’t see anybody get killed so things weren’t bad for me. But the war messed up a lot of minds.”

Compared to many other veterans, Bibby emerged from the war relatively unscathed. But his service in the Army did cost him two full years of minor league time, thereby delaying his major league arrival.

Finally discharged in January of 1968, Bibby returned to the Mets’ organization and reported to their affiliate in the Carolina League. There he greatly improved his control, which had been horrendous during his rookie season. With better control of his overpowering fastball, Bibby lowered his ERA to 2.82 and struck out 118 batters in 131 innings.

Based on the strength of that performance, the Mets invited him to Spring Training in 1969, before assigning him to Double-A Memphis. He pitched so well there that he earned a promotion to Triple-A Tidewater in July. From there, the Mets promoted him to New York in September. Bibby never actually appeared in a game for the “Miracle Mets,” but did participate in the team’s celebration that followed the clinching of the newly formed National League East.

With any luck, Bibby would have made the Mets’ Opening Day roster in 1970. But health would not permit that. One day, while trying to cover first base in a Grapefruit League game, Bibby injured his back, which was already bothered by a congenital bone spur. Doctors determined that Bibby needed spinal fusion surgery, a major procedure that gave him only a 50 percent chance of ever pitching again. The surgery, which involved a piece of bone from his hip being removed and then reattached to his spine, left him with two mammoth scars.

After the surgery, Bibby missed all of the 1970 season. Successfully able to rehabilitate his back, Bibby made a remarkable comeback in 1971. He pitched most of the season at Tidewater, before earning a late-season promotion to New York, but once again did not appear in an actual game for the pitching-rich Mets.

The lack of an opportunity to pitch frustrated Bibby. That’s why he welcomed the news that came that winter: An eight-man trade that landed him and veteran outfielder Art Shamsky in St. Louis. The Mets would come to regret the deal. Although they were flush with pitching at the time, left-handed ace Jerry Koosman was facing injury problems. Furthermore, the organization would soon part with a young Nolan Ryan, lessening the depth of the staff even further.

Somewhat surprisingly, the Cardinals did not include Bibby on their Opening Day roster. Instead they optioned him to Triple-A Tulsa, where he dominated minor league hitters. In September, Bibby received a call to the major leagues, and finally made his debut – at the age of 27. Making six starts, Bibby pitched creditably, to the tune of a 3.35 ERA.

The Cardinals hoped that Bibby could become a fulltime starter in 1973, but he pitched so poorly in six early-season appearances that the organization lost patience. In early June, the Cardinals traded him to Texas for young catcher John Wockenfuss and pitcher Mike Nagy. The deal was heartily endorsed by new Rangers manager Whitey Herzog, who knew Bibby well from his days overseeing the farm system of the Mets.

Fully believing in Bibby, Herzog made the big right-hander part of his five-man rotation. Finally given a long-term opportunity, Bibby emerged as a highly capable starter. In July, he made headlines when he fired a no-hitter against the defending world champion Oakland A’s. Bibby threw 148 pitches that day, the last pitch resulting in a short fly ball to right field, caught by Dave Nelson. Bibby relied mostly on his 95 mile-an-hour fastball, which he used to pile up 13 strikeouts. He was also wild that day, issuing six walks, but the wildness only made him more intimidating to Oakland hitters.

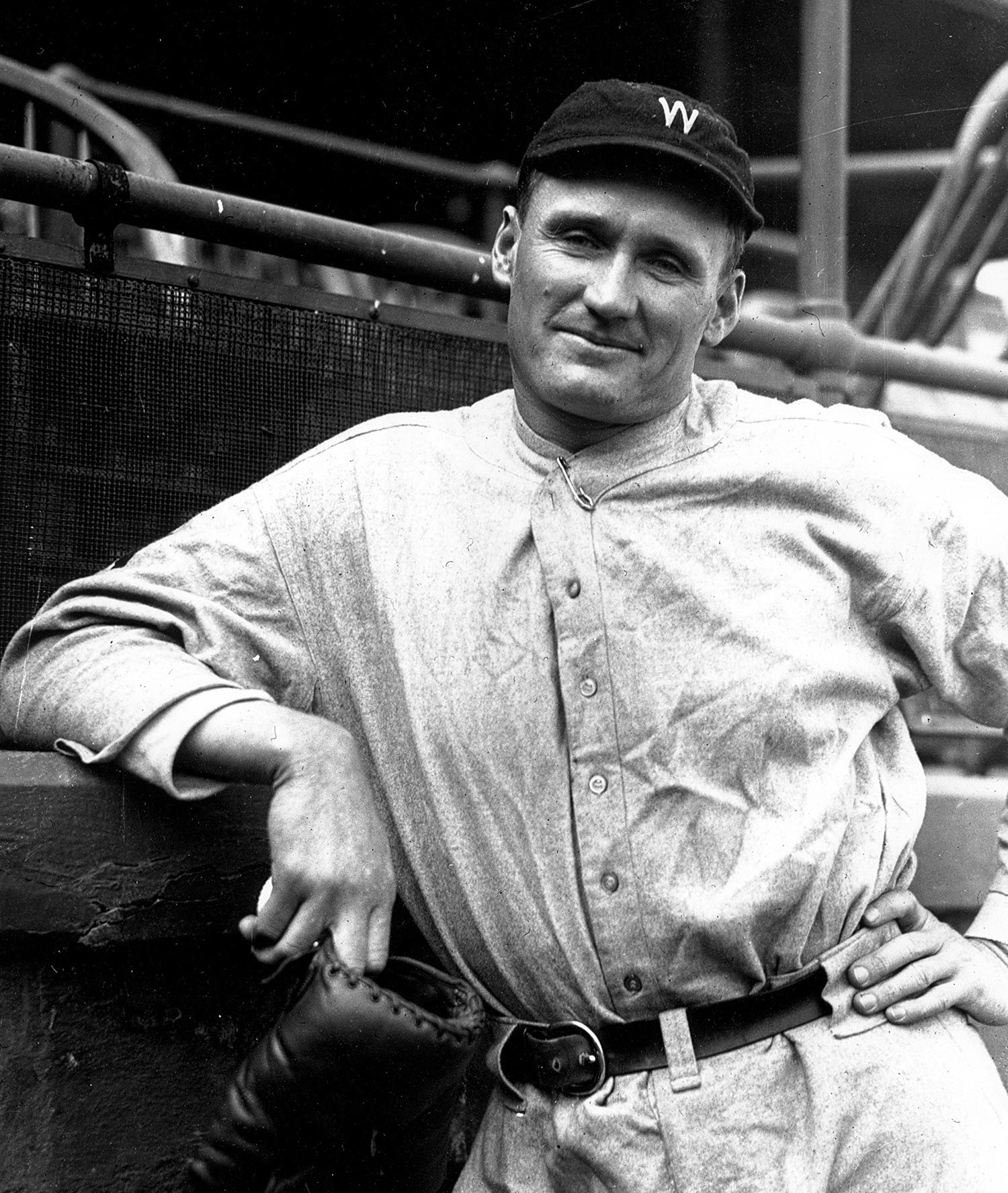

The no-hitter represented the first for the Rangers since the franchise move to Texas in 1972. Including the years with both Senators’ franchises, Bibby’s gem was the third in modern Washington history. The first had taken place in 1920, authored by a fellow named Walter Johnson. “Man, that’s just fast company,” Bibby told sportswriter Merle Heryford when informed of the Johnson connection. “Now they want my cap and the ball that Dave [Nelson] caught for Cooperstown. Can you imagine that? I never thought this would happen.”

Although the game was played in Oakland, and not Texas, Bibby perspired heavily that afternoon – as was usually his custom. By his own estimate, he lost 10 pounds. As a reward for his effort, Rangers owner Bob Short gave Bibby an immediate $5,000 raise, significant money for a ballplayer in those days.

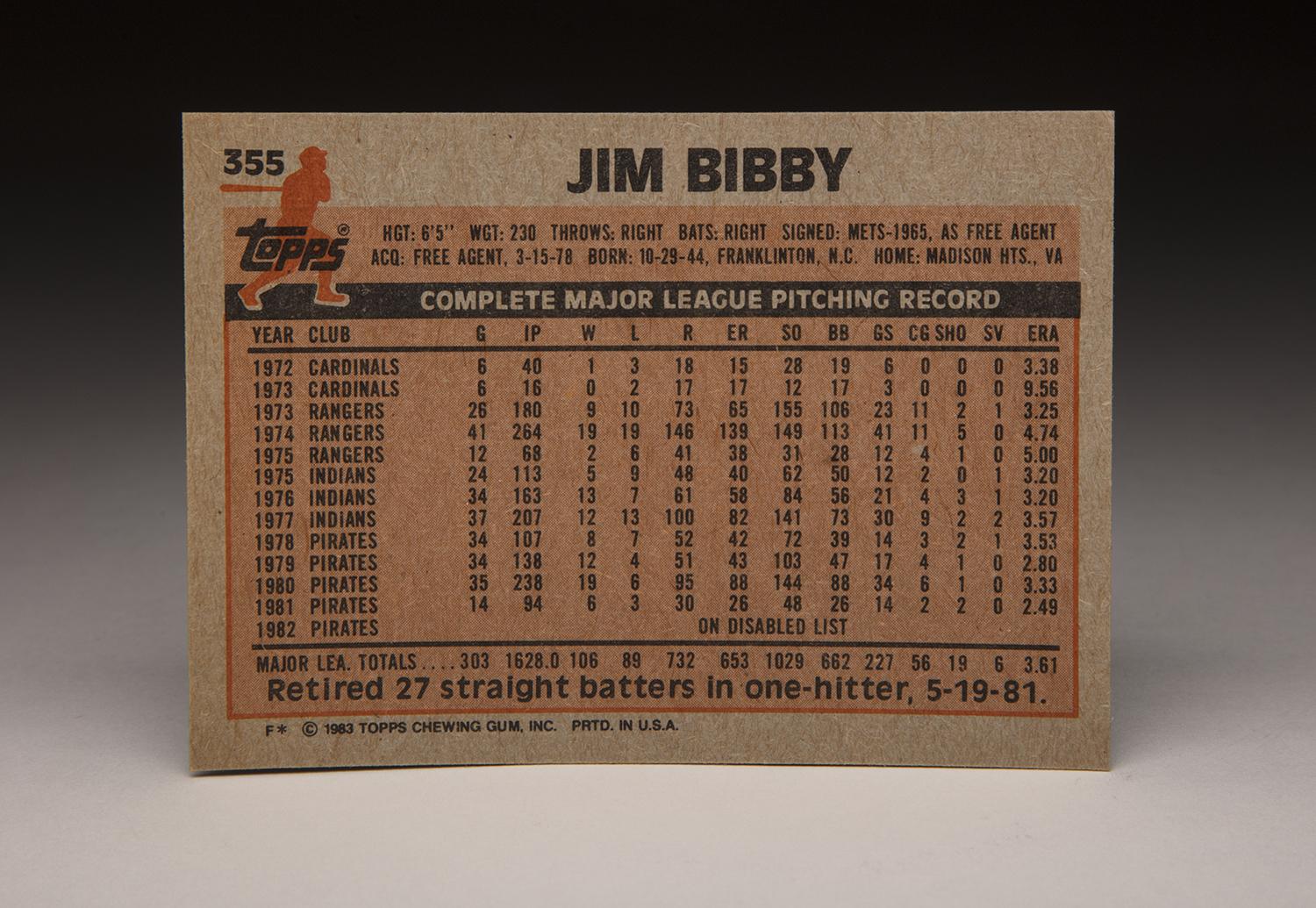

In 1974, Bibby became a workhorse for the Rangers, even though the quality of his pitching fell back. He made a remarkable 41 starts, logging 264 innings and winning 19 decisions. He struck out 149 batters, but also walked 113. On days he pitched well, he could be dominant. But in games that he lost, 19 in total, his ERA soared above 9.00.

The 1975 season would become a crossroads campaign for Bibby. The Rangers hoped that he would turn the corner, but he instead struggled over his first 12 starts. Running out of patience with the enigmatic right-hander, the Rangers made a trade in midseason. In acquiring ace Gaylord Perry from the Cleveland Indians, the Rangers surrendered Bibby and two young pitchers, Rick Waits and Jackie Brown.

The trade turned out to be the perfect remedy for Bibby. Indians pitching coach Harvey Haddix went to work on the tall right-hander, smoothing out his delivery and improving his control. Over a stretch of two and a half seasons, Bibby pitched capably for the Indians, mostly as a starter but occasionally as a reliever. He also became quite a sight wearing the Indians’ all-red uniforms of 1975. With Bibby and another oversized teammate, Boog Powell, wearing the “blood-clot” specials, the Indians became one of the most unique looking teams of the 1970s.

In the spring of 1978, Bibby was allowed to become a free agent, but not under the usual circumstances. The Indians delivered a bonus payment of $10,000 past a stated deadline, with the violation representing a breach of contract. Nine days after the ruling, Bibby signed a six-year contract with Pittsburgh, giving him a chance to pitch closer to his home in West Virginia. Bibby also liked the talent level of the Pirates, a team that seemed on the verge of making a run at the National League pennant.

Bibby fit in beautifully with the Pirates, whose cast of clubhouse characters included pranksters and jokesters. With his outgoing personality and sense of humor, Bibby felt right at home. Over the next two seasons, manager Chuck Tanner used Bibby as a swingman, capable of long relief and starting. Over that span, Bibby won 20 games, lost only 11, and became Tanner’s jack-of-all-trades. In 1979, Bibby led the National League with a .750 winning percentage, most appropriate for a team headed to the postseason.

For the first time in his career, Bibby made appearances in the playoffs and World Series. Although he did not register a decision in one start against Cincinnati and two against Baltimore, he pitched well in his three appearances, as the Bucs took home the 1979 world championship – with Bibby starting the deciding Game 7 against the Orioles.

In 1980, Tanner rewarded Bibby with a fulltime berth in the rotation. Adjusting his approach by not throwing his fastball at maximum effort with each pitch, Bibby again led the league in winning percentage, taking home 19 victories while logging 238 innings. Thanks in part to his “less is more” approach, Bibby also made the All-Star team for the first time in his career.

And he started the 1981 season just as strong. On May 19, Bibby began a game against the Braves by allowing a single to right field by Terry Harper. He then retired the next 27 men in a row for a one-hitter, becoming one of the few pitchers in big league history to record 27 straight outs in a single game. The outing is noted on the back of his 1983 Topps card.

But following the 1981 strike, shoulder pain limited Bibby to just four starts in the second half – finishing the season with a 6-3 record and 2.50 ERA in 14 appearances. The following April, Bibby underwent rotator cuff surgery.

At the time, rotator cuff surgery usually represented the death knell of a pitcher’s career. Bibby missed all of 1982, and then tried to come back in 1983, but his ERA rose to 6.69. Although he had returned to action with good velocity, his poor location resulted in numerous early game knockouts.

After the season, Bibby became a free agent. He decided to return to Texas, but his second tenure with the Rangers lasted only eight games. By July of 1984, the Rangers released him. From there, he signed on with the Cardinals’ organization, pitching at Triple-A briefly but soon drawing his release. Now 39 years old, Bibby realized that it was time to retire.

With his playing career behind him, Bibby turned to life as a minor league pitching coach, a natural fit for his outgoing personality. After a brief stint with the Durham Bulls, he began a long-term association with the Lynchburg Hillcats, located near his Virginia home, in 1985.

Bibby became something of a cult figure in Lynchburg, signing autographs before and after games and taking time to chat with fans who had questions about his playing days.

Bibby became so popular that the team held a bobblehead night in his honor.

Bibby remained at Lynchburg through 2000, when he agreed to move on to Nashville, at the time the top affiliate of the Pirates. After the season, he had to undergo double knee replacements; the surgery convinced him that it was time to retire. He retired to a life of playing golf, attending church and doing charity work for a number of organizations.

Sadly, Bibby was diagnosed with bone cancer in his later years. In 2010, he succumbed to the disease at the age of 65. For many of his friends and former teammates, it was hard to believe that this massive man, so large and strong, had been taken at such a young man.

Shortly after his passing, one of his former teammates paid tribute to Bibby by referencing his deceptive physical appearance. To a stranger, the 250-pound Bibby might have been an intimidating sight, but those who became friends with him knew otherwise.

“You saw Bibby, that size, and you’d think of this giant of a man,” former Pirates closer Kent Tekulve told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “Yet his personality didn’t fit his size at all. Just a very gentle, caring person who just happened to be a great pitcher.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

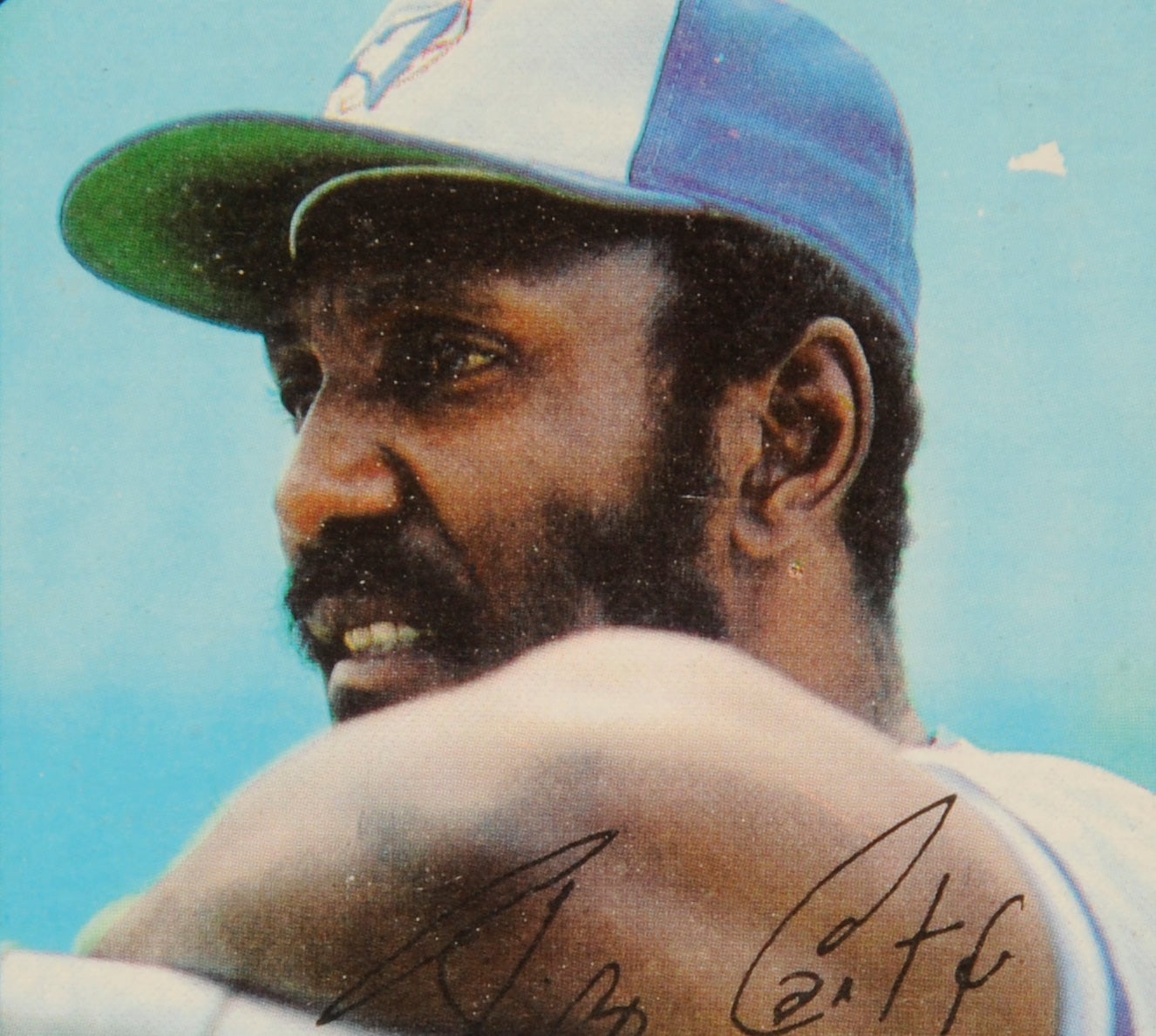

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty

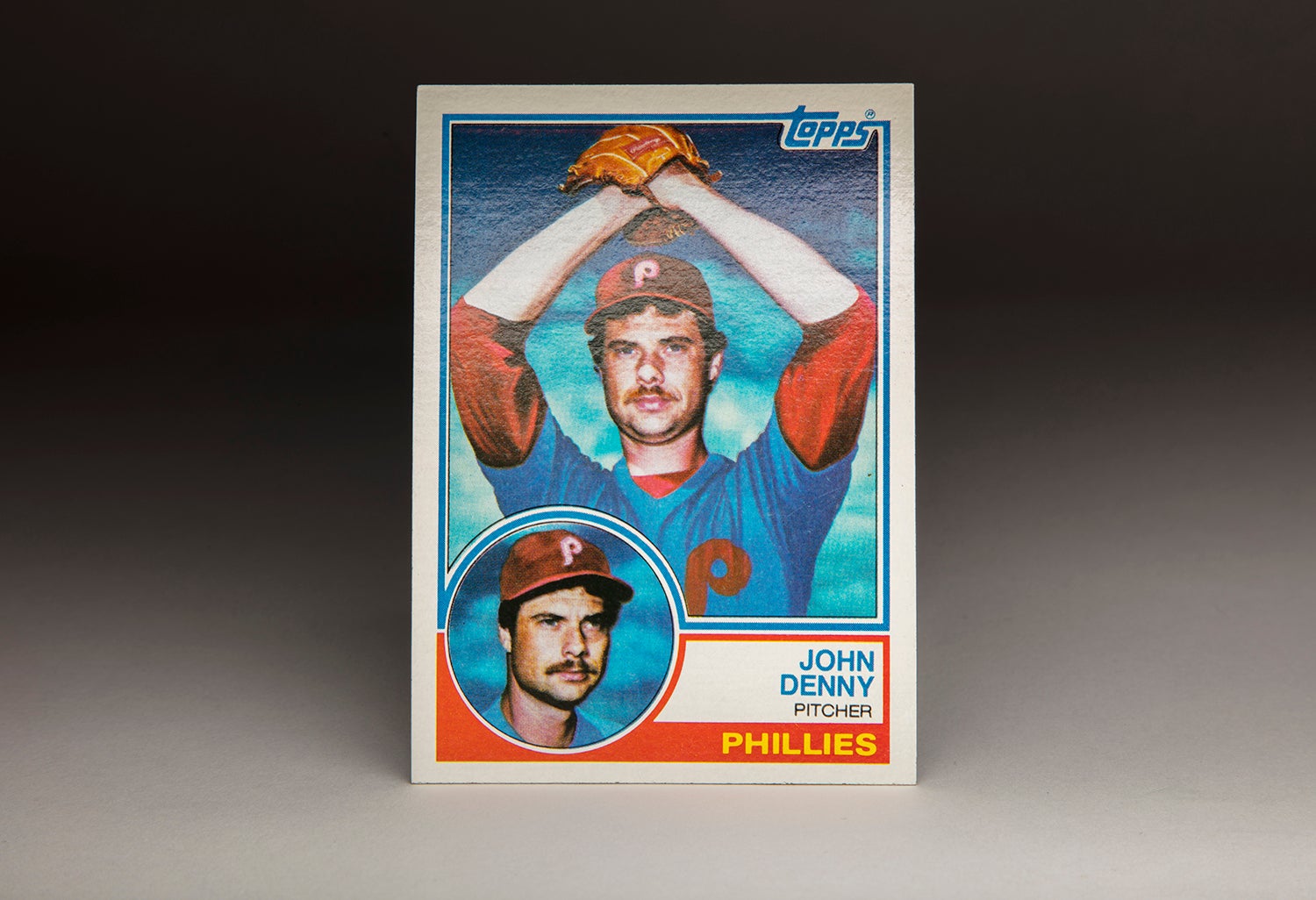

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Denny

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Mayberry

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Reggie Smith

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Rico Carty

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Denny