- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Denny

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps John Denny

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

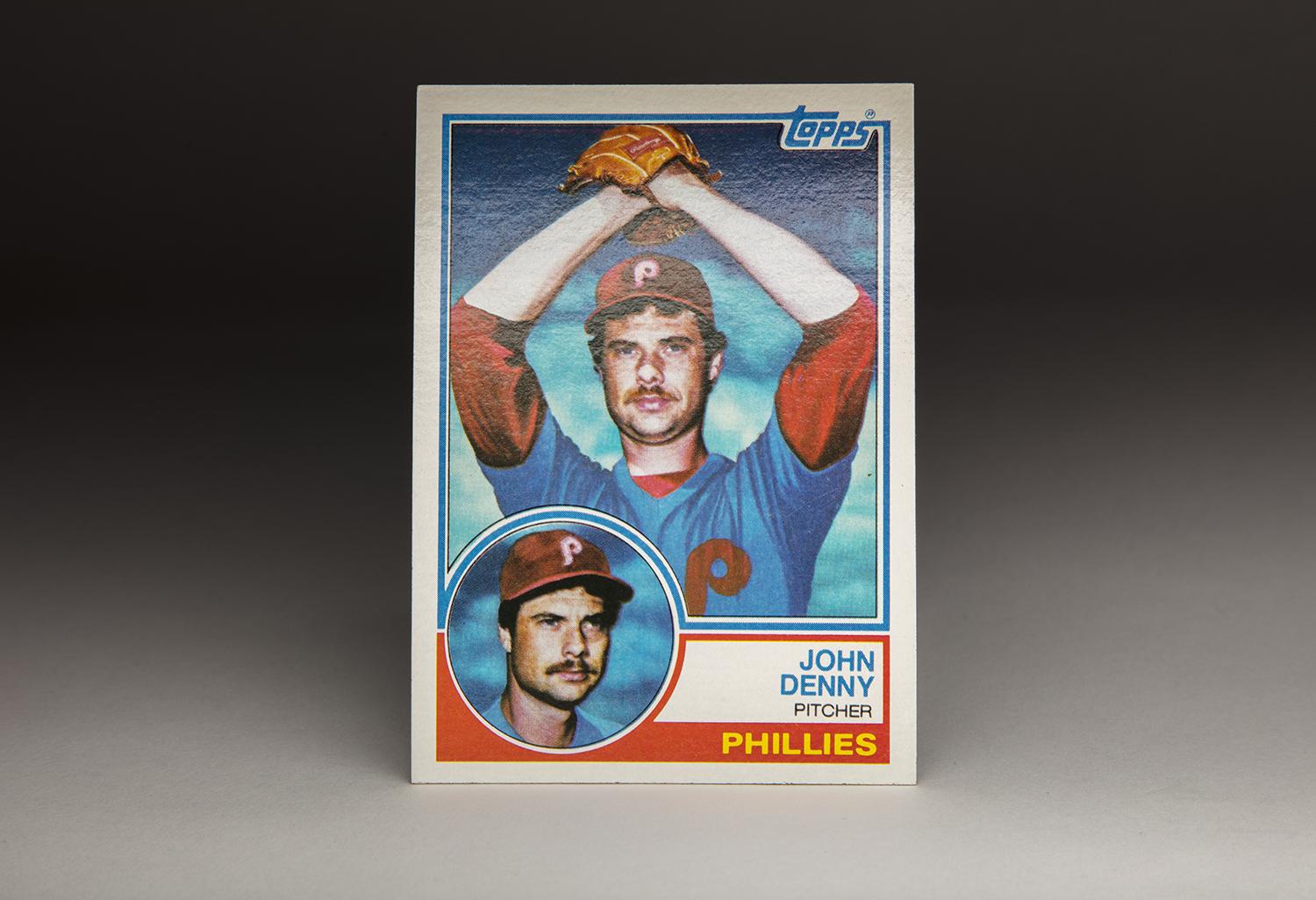

It’s bizarre. It’s surreal. And just plain weird. Not quite photographic. If it’s not a picture, might it be a painting, perhaps? Or maybe it’s all just an illusion.

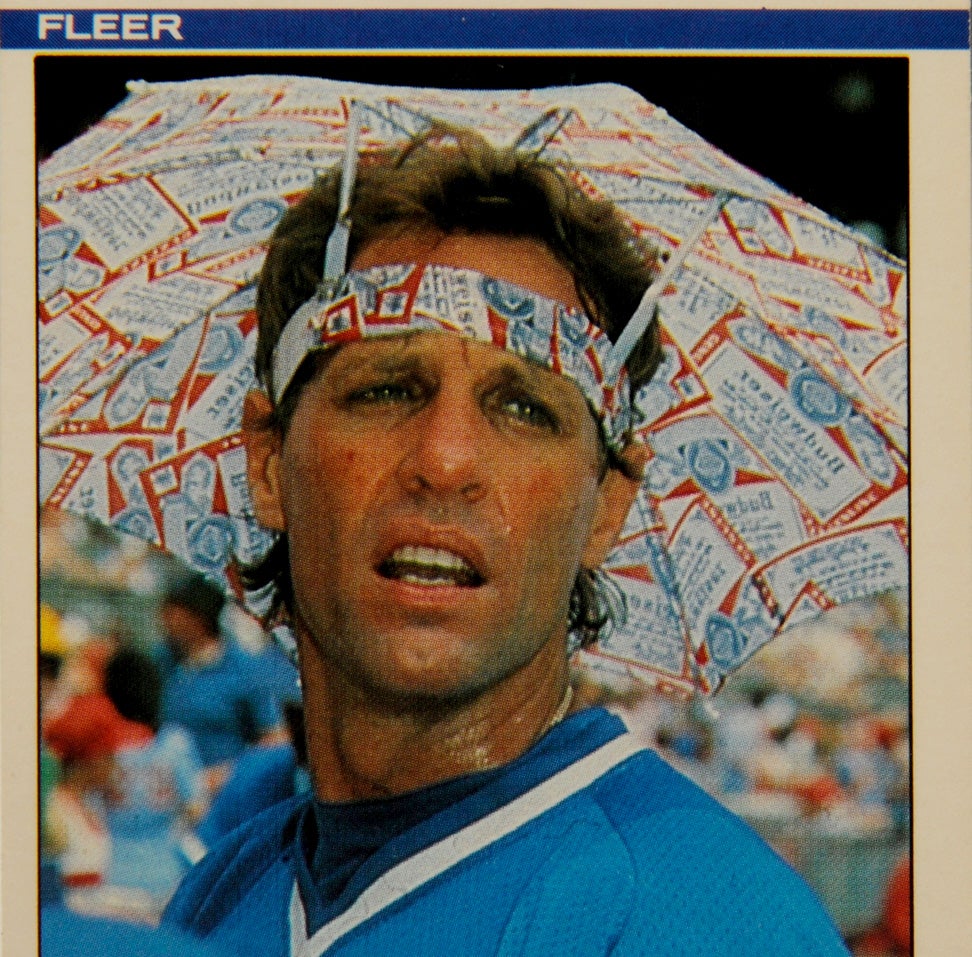

These are all thoughts that come to mind whenever I take a gander at John Denny’s 1983 Topps card. It’s one of the strangest cards that Topps has ever produced. Obviously, this card involves some heavy airbrushing, but it doesn’t seem to involve only Denny’s Philadelphia Phillies colors, which have been drawn on top of a previous team’s uniform. It also appears that the dark blue sky background has been airbrushed, for reasons that remain unknown to me. Because of the airbrushing, those clouds look like storm clouds. And then, if you take a closer look at Denny himself, you might begin to think that even his face has been airbrushed.

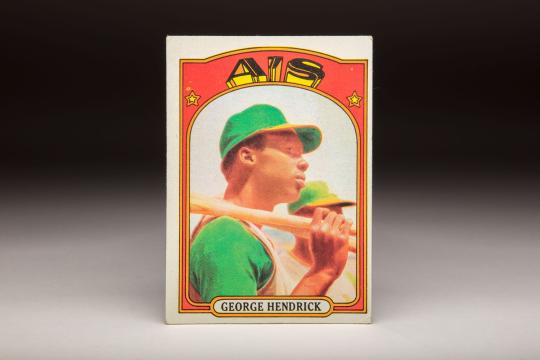

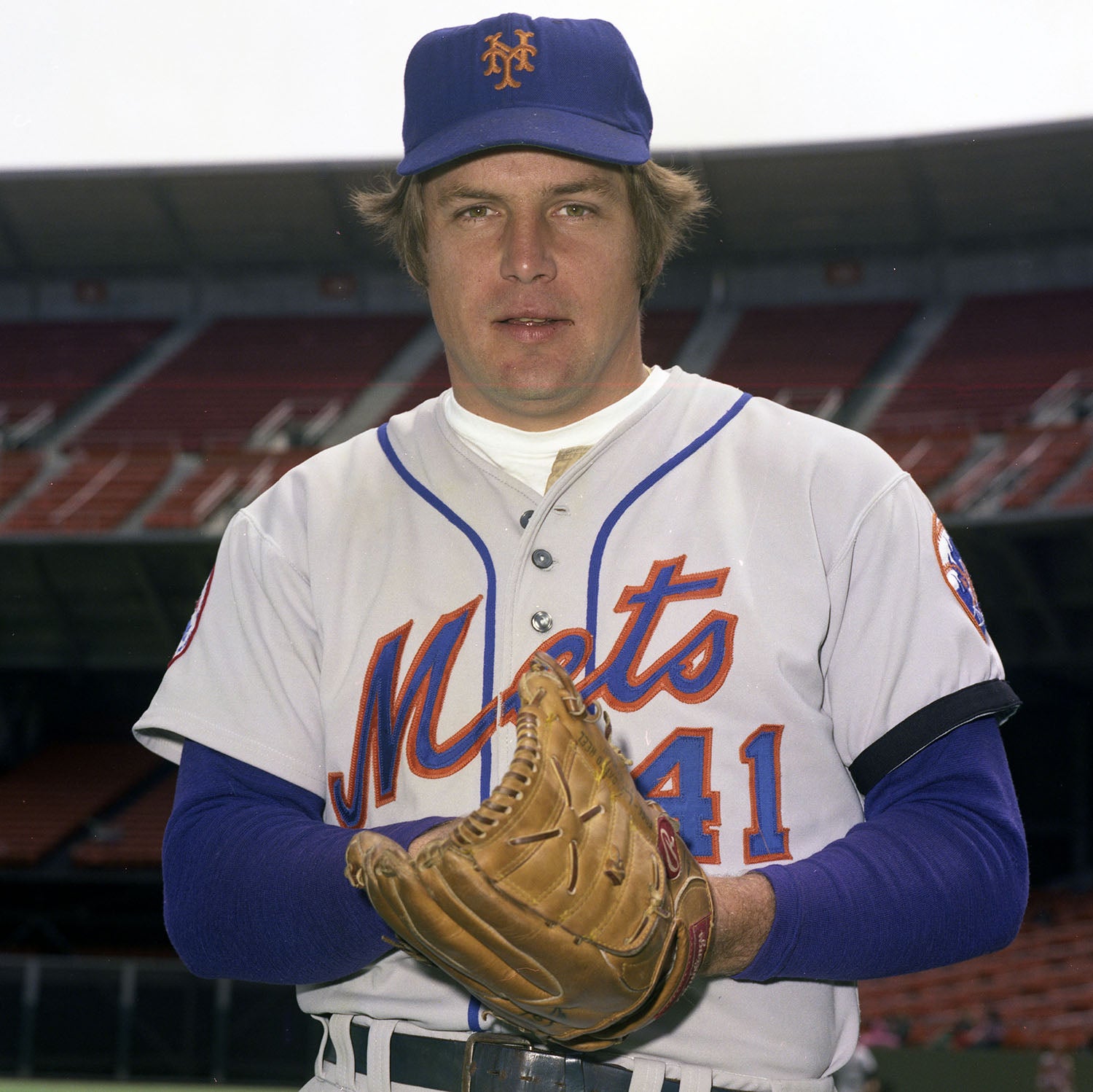

If that’s the case, if the player has been airbrushed, well it’s actually something that Topps did with previous cards. In 1972, Topps issued a card of George Hendrick that was airbrushed in such a way. (That card was the subject of an earlier Card Corner.) In 1977, Topps put out a similar card of Seattle Mariners pitcher Rick Jones. The entire card is airbrushed. So is Mike Paxton’s 1978 Topps card. As is Greg Minton’s 1978 Topps card.

In most of these cases (except for Hendrick), Topps had only black-and-white photographs of the players in question. Rather than issue a black-and-white card in a set that otherwise featured color, Topps decided to colorize the entire photo, in a way that is eerily reminiscent of Ted Turner’s efforts to colorize old black-and-white films back in the 1980s. As a result, each of these cards looks more like a painting, or a drawing, than an actual photograph.

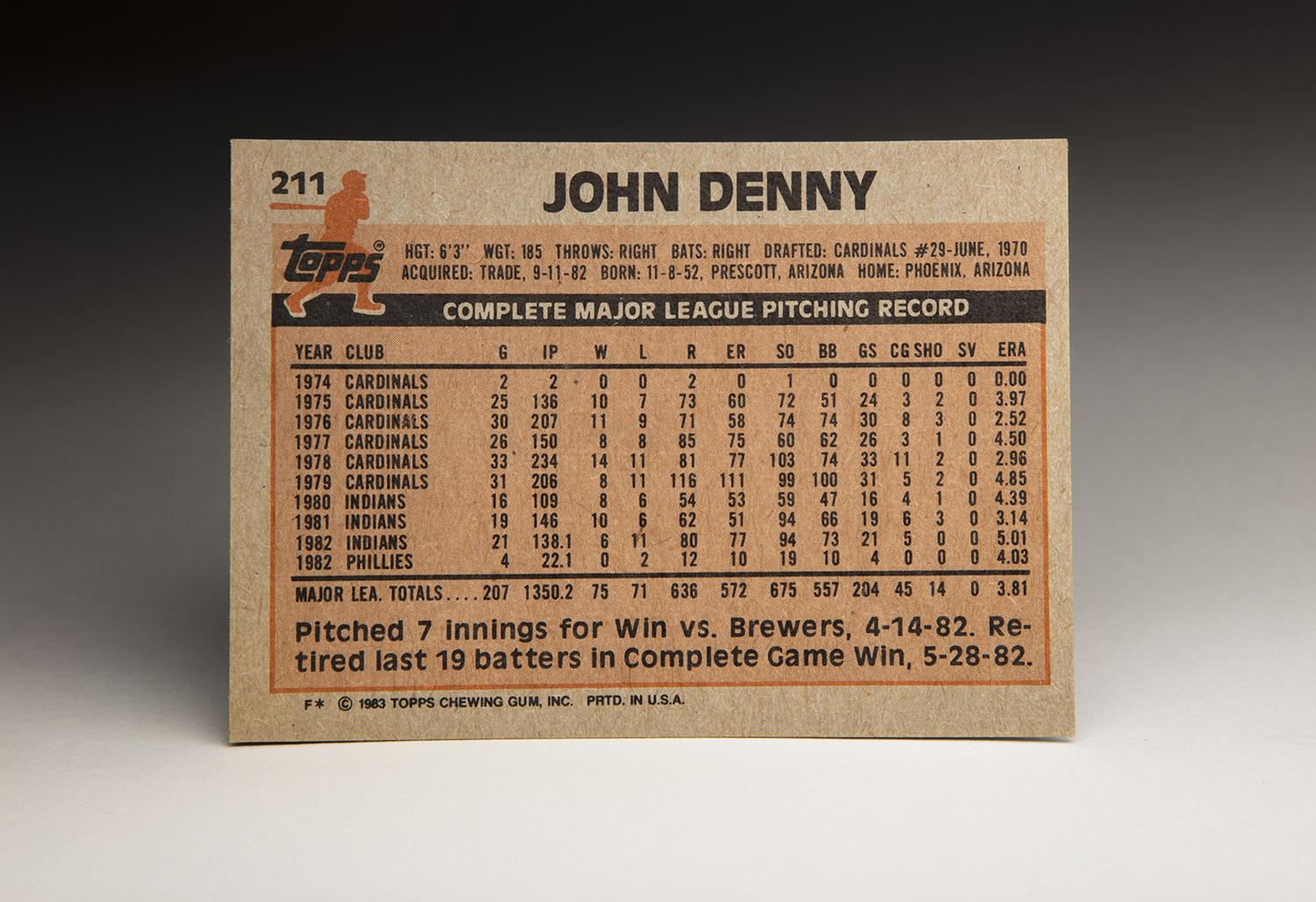

Traded from the Cleveland Indians to the Philadelphia Indians on Sept. 12, 1982, Topps didn't have an image of John Denny in a Phillies uniform. So with the help of airbrushing, their artists created one of the most unusual cards in the 1983 Topps set. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Here’s what I don’t understand. In the case of Hendrick, Jones, Minton, and Paxton, they were all appearing on Topps cards for the first time. So Topps probably had a very limited library of photographs to choose from. In the case of Denny, he had been pitching in the big leagues since 1975, when he joined the St. Louis Cardinals. He had appeared on cards annually since 1976. Topps had plenty of photographs of Denny in color. So why did they resort to using a black-and-white photograph and then coloring over it?

My guess is that this is not a black-and-white photograph that has been colorized. I think it’s a color photo, but the Topps artist became a little overzealous in his efforts to airbrush it. Of course, that’s just a guess. Whatever the case, the card is weird, without a doubt, but it’s weird in a way that I like. This card, as strange as it is, is just cool.

By the time his 1983 card came out, Denny was still somewhat of a pedestrian name in baseball circles. That would change later in ’83, when he won the National League’s Cy Young Award and vaulted himself to household status.

Denny’s career began more than a decade earlier. Before that, he had grown up in a broken home, the result of his parents divorcing. His mother raised him by herself; he would go long stretches without hearing from his father.

Despite the difficulties of his family life, Denny pitched well enough as an amateur to draw the attention of the St. Louis Cardinals. The Redbirds drafted him in 1970, but not until the 29th round. As a later draft choice, Denny was no sure-fire, “can’t-miss” phenom. He faced an uphill struggle, the odds heavily against him eventually making the major leaguers. Those odds became greater as he struggled with pain in his right elbow.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Still, four years after signing his first contract, Denny made it; the Cardinals brought him to St. Louis as part of their September call-ups in 1974. He pitched in two games in relief, giving up a couple of unearned runs. But all of that seemed trivial to what happened one day that September, when he received a call that his older brother, Gary, had been shot and killed by his own wife. A painful trial ensued, with his brother’s wife allowed to go free on a technicality.

In the spring of 1975, the Cardinals included Denny on their Opening Day roster, but watched him struggle. So they sent him back to Triple-A Tulsa, where he made seven starts, pitching well. Believing that he was deserving of another chance, the Cardinals brought Denny back in June and once again made him part of their rotation. This time, Denny was ready. He pitched a shutout in his first game back, and then strung together a number of serviceable starts. Occasionally, he found himself being hit hard, but all in all, he compiled an impressive set of statistics for a rookie: 136 innings, a 3.97 ERA, and a record of 10-7.

Some young players struggle as sophomores, but the so-called “sophomore jinx” had no effect on Denny. He won 11 games, but with better run support, he might have made a run at 20. He compiled a 2.52 ERA in 207 innings, earning the National League’s ERA championship. In winning the ERA title, Denny beat out a number of brand-name pitchers, including Tom Seaver, Jerry Koosman and Jon Matlack of the Mets, Houston’s hard-throwing J.R. Richard and John “The Count” Montefusco of the San Francisco Giants. He did all of this despite an odd strikeout-to-walk ratio of 74 to 74.

Denny hoped to cut down on his walks and continue his emergence as one of the National League’s best pitchers in 1977. He started the season well, winning his first five decisions. Sports Illustrated ran a piece about the young right-hander, in which they emphasized Denny’s hot temper. Denny hated the article, which he claimed made him seem “like a psycho.” Affected by the negative article, Denny fell into a deep slump. By season’s end, his ERA had risen to 4.51. His walks actually exceeded his strikeouts.

The pattern of one good year followed by a bad one continued over the next two seasons. After a solid 1978, he plummeted in ’79; his ERA rose to 4.85, while his walks total increased to an even 100. Denny had always been wild, uncomfortably wild for most hitters, but now he had reached the stage of simply being erratically wild. He also found it difficult to pitch because of pain in his ankle, a problem that would require surgery after the season.

Denny’s problems involved more than his ankle and his wildness. Throughout his Cardinals career, he had struggled with his temper, which put him into battles with his coaches and teammates. He also argued with members of the media, before boycotting them completely. As Denny admitted in later years, “I was a lost soul.”

By 1979, the Cardinals felt it was time to trade Denny. They included Denny and switch-hitting outfielder Jerry Mumphrey in a package, sending them to the Cleveland Indians for the well-traveled Bobby Bonds.

The Indians liked Denny’s moving fastball and terrific change-up, along with his toughness and his willingness to pitch inside. But he was not healthy, bothered by an injured ankle that badly affected his pitching motion. Limited to only 16 starts because of injury, Denny won only eight games and posted an ERA of 4.39.

Then came a breakthrough during the strike-shortened season of 1981. Healthy again, Denny won 10 games, crafted an ERA of 3.15, and struck out 94 batters against 66 walks.

The timing proved to be good for Denny, who was now a free agent. As a live-armed right-hander who was still only 28 years old, Denny drew interest from several other teams. As a fan of the New York Yankees at the time, I hoped that Denny would sign with them. The Yankees had plenty of left-handed pitching, but lacked a proven right-handed starter. Denny seemed like a perfect fit.

The Yankees did not sign Denny, even though they offered him substantially more money than any other bidder. Denny rejected the offer, saying that he did not want to “subject myself at this time to the environment of the New York Yankees.” He cited Yankees owner George Steinbrenner for being “demanding and irrational.” Rather than join the Yankees, Denny returned to the Indians, who signed him to a contract paying him just over $1 million per season.

Strangely, Denny continued his pattern of putting up bad seasons after good ones. He flopped in his return to Cleveland, hampered by a sore shoulder that left him with a record of six wins and 11 losses. With his ERA over 5.00, Denny became trade bait. In September, the Indians traded him to the Phillies for three unproven players, outfielder Wil Culmer and pitchers Jerry Reed and Roy Smith.

Thanks to the late-season trade, Topps did not have an updated photograph of Denny wearing the colors of the Phillies. That’s why Topps went airbrush crazy, producing the most unusual card of the 1983 set. Just as strangely, no one could have anticipated the card would depict the winner of the next Cy Young Award.

Denny reached career highs in just about every major category, including innings pitched (242), strikeouts (139), wins (19) and ERA (2.37). Led by Denny, who not only won the Cy Young but received support in the MVP voting, the Phillies finished first in the National League East and advanced to the World Series against the Baltimore Orioles. Denny started and won Game 1, but the Phillies lost the next four as they came up short of their second world championship in four years.

While the veteran right-hander had transformed his pitching, he had also succeeded in changing his life. He became reborn spiritually, committed to eliminating the temper tantrums that had plagued him. He apologized to those he had wronged along the way. He also received some help. Phillies strength coach Gus Hoefling worked with him on his physical conditioning. Phillies pitching Claude Osteen provided counsel, as did his teammate, Steve Carlton. The future Hall of Famer worked with him on his concentration and focus, particularly while he was on the mound.

Denny continued to pitch well in 1984, but arm woes limited him to 22 starts. He bounced back with a full season in 1985, but the Phillies decided to trade him that winter, sending him to the Cincinnati Reds for outfielder Gary Redus and reliever Tom Hume.

George Hendrick's 1972 Topps card was airbrushed in a similar way to John Denny's 1983 card. Read more about it here. (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame)

In 1986, Denny pitched decently for the Reds, winning 11 games, but he left the team before the end of the season because of a strained wrist. It had been a difficult year for Denny, who in May had become involved in an altercation with Cincinnati Post sportswriter Bruce Schoenfeld. According to witnesses, Denny accused the writer of trespassing in the Reds’ clubhouse, then threw him up against a wall and made threats against him. Sadly, it was a return to the kind of erratic, volcanic behavior that had plagued Denny during his days in St. Louis.

With his wrist and his reputation hurting, no teams showed interest in him. Only three years after winning the Cy Young Award, Denny found no suitors. He decided to retire, even though he was only 33 years old.

Since his retirement, little has been written about Denny, who worked briefly as a rehabilitation coach for the Arizona Diamondbacks organization but is now out of baseball. He always preferred an at-arms-length relationship with the media, perhaps because of the difficulties of his early family life and the loss of his brother, allowing little insight into his personality or his post-baseball life.

In a way, Denny remains as mysterious as his 1983 Topps card remains surreal. So many questions remain, about both Denny and his card. I guess that makes him and the card even more interesting.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

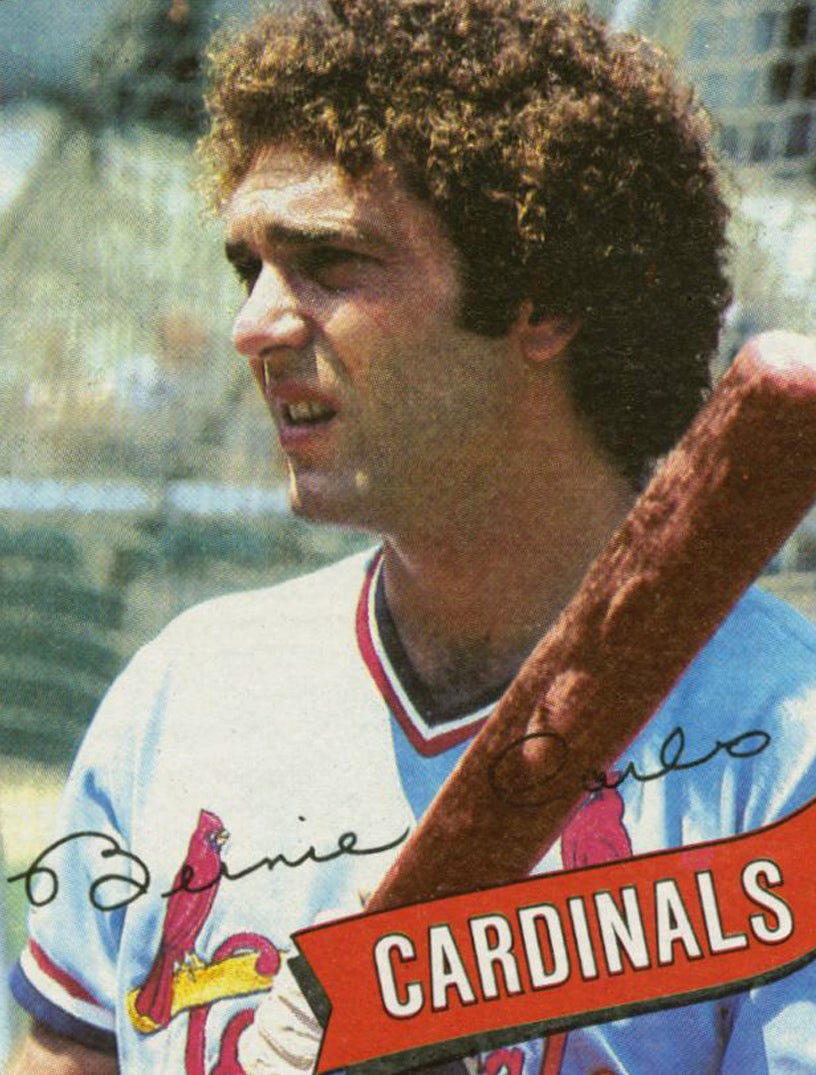

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

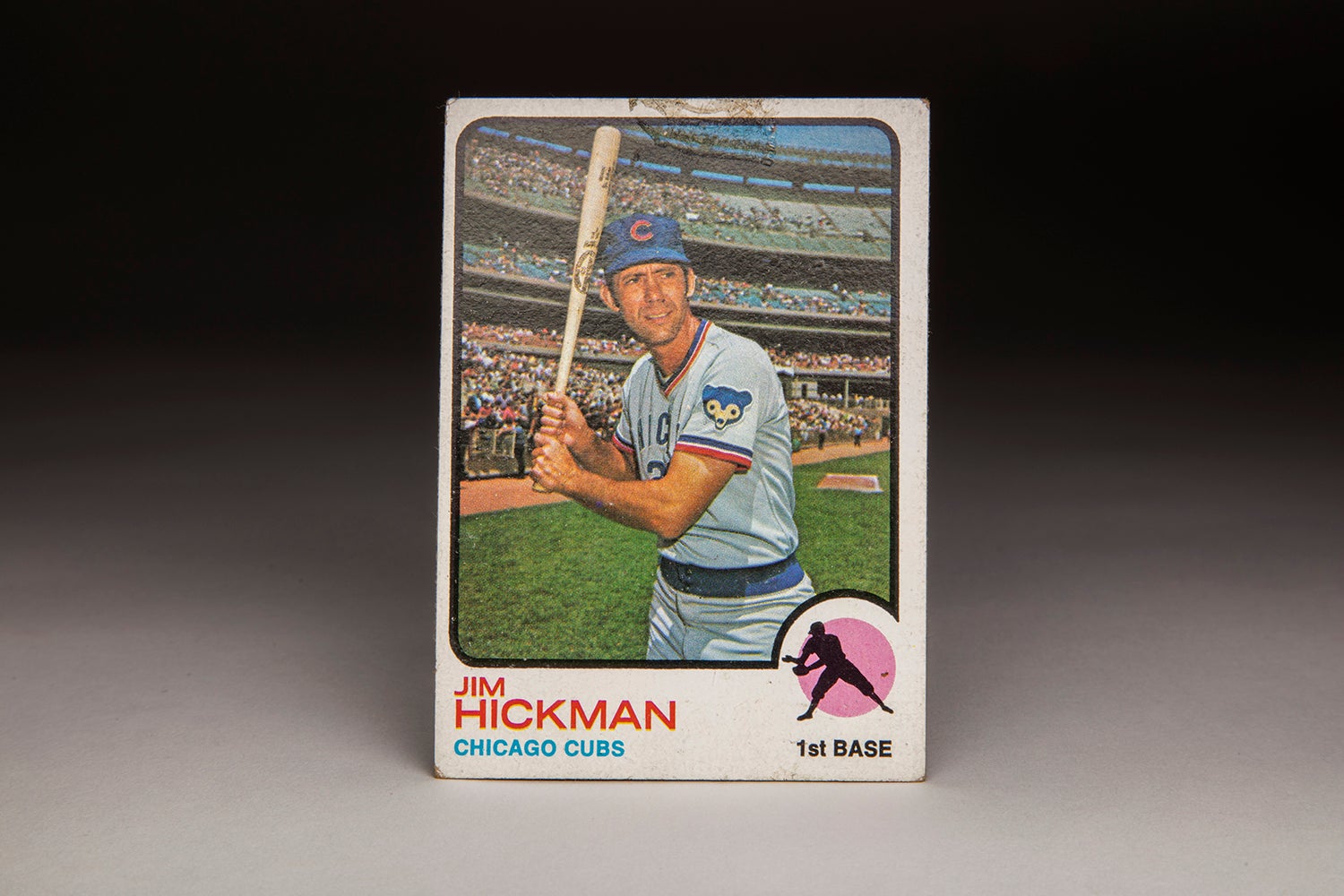

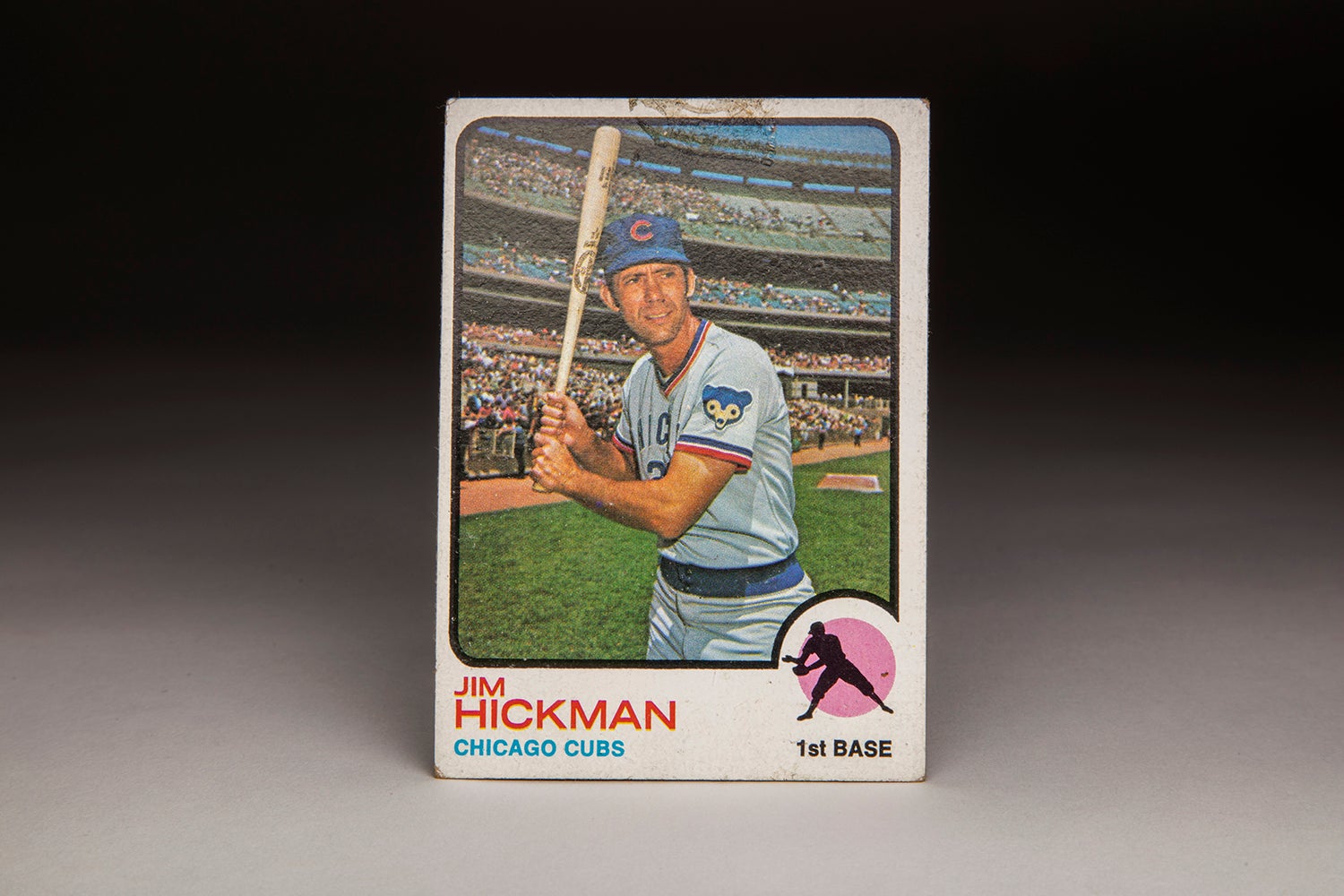

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Jim Hickman

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo