- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Fleer Johnny Grubb

#CardCorner: 1983 Fleer Johnny Grubb

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Young baseball fans can be cruel toward major league ballplayers. Growing up in Westchester County, where I attended Iona Grammar School, I was not exempt from such behavior, at least in terms of how it applied to the National Pastime.

My friends and I liked to make fun of player names, some of which rhymed, some of which sounded weird, and some of which lent themselves to poking the proverbial needle. One of the latter players was Johnny Grubb. Naturally, some of us baseball novices started referring to him as “Grubb The Scrub.” I suppose we could have been less obvious and come up with “Grubb The Flub,” but that would have required too much creativity on our part.

Grubb was not a star nor a household name, so we simply assumed that he was a “scrub.” It’s a term that has fallen by the wayside in recent years but was once common in the sports vernacular. A scrub is a backup player, or a utility infielder, maybe the last man on the 25-man roster. Scrubs are usually below average players, at least in comparison to their major league counterparts. It turns out that we didn’t know much about Grubb; he was a much better player than any of us knew. He even made an All-Star team. For me, the appreciation for his true value would come later in my life, and would only grow when I had a chance to meet the personable Grubb for the first time.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

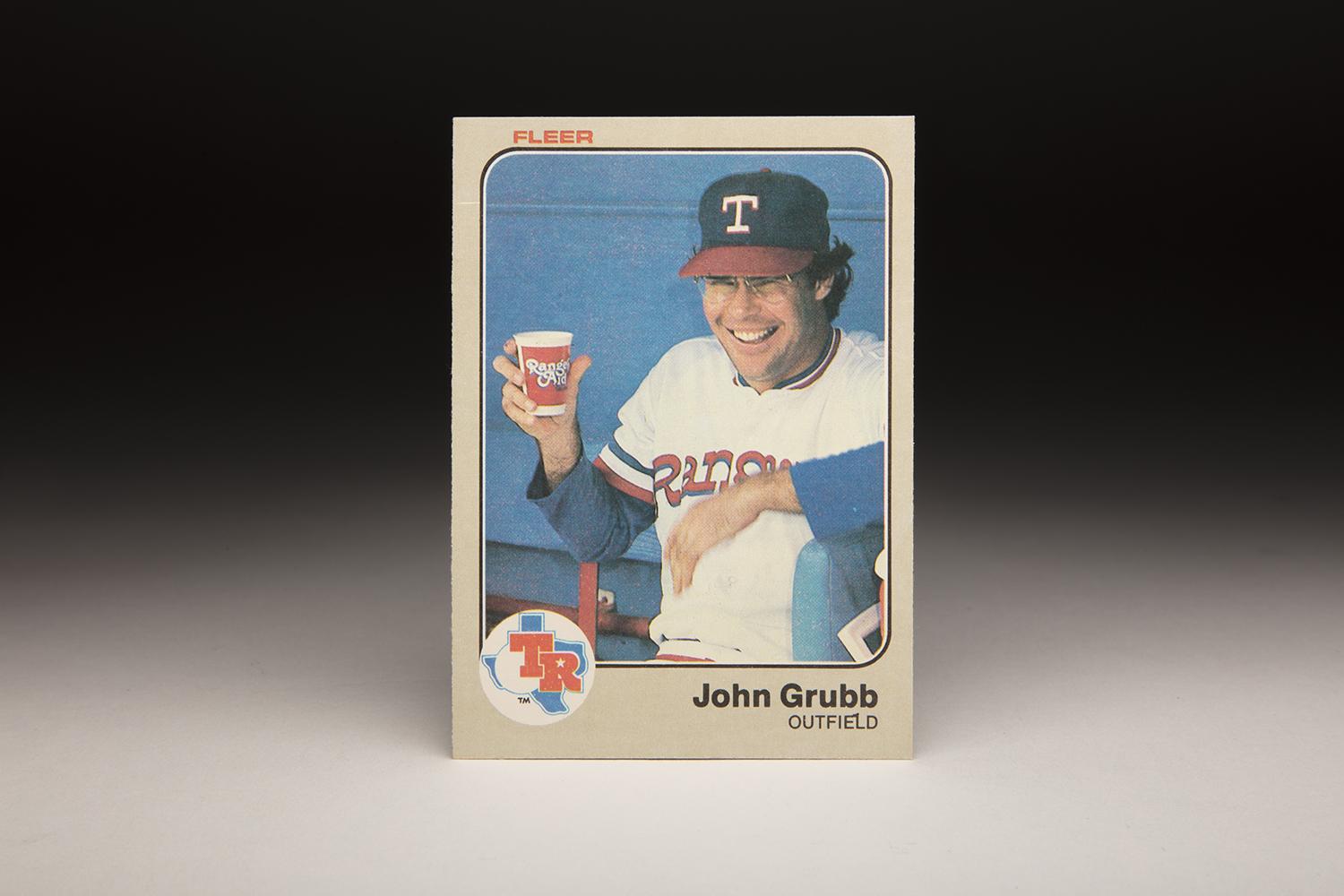

Of all the Johnny Grubb cards, the most memorable is the one that was featured in the 1983 Fleer set. It’s a quality set, featuring the distinctive gray borders that set it apart from most other card sets of the 1970s and eighties. The Fleer set is hallmarked by some intriguing action shots, a few of which were taken from unusual angles. It’s also a set in which Fleer decided to have some fun, by capturing a few players in less than standard poses.

Certainly, the Grubb card falls into the latter category. Either by his own choice, or at the behest of the Fleer photographer, Grubb can be seen proudly holding up a cup of “Ranger Ade,” almost as if he were showcasing it as part of a local television commercial. With a jovial smile and a full-handed grip on the paper cup, Grubb appears to be a genuine fan of Ranger Ade, which I can only guess was some sort of sports drink. Perhaps it was the Texas Rangers’ version of Gatorade, the drink that first came into popularity in the 1960s. Given the heat and humidity of Texas, not to mention Spring Training in Florida, something like Ranger Ade could have come in quite handy for anyone on the Texas roster.

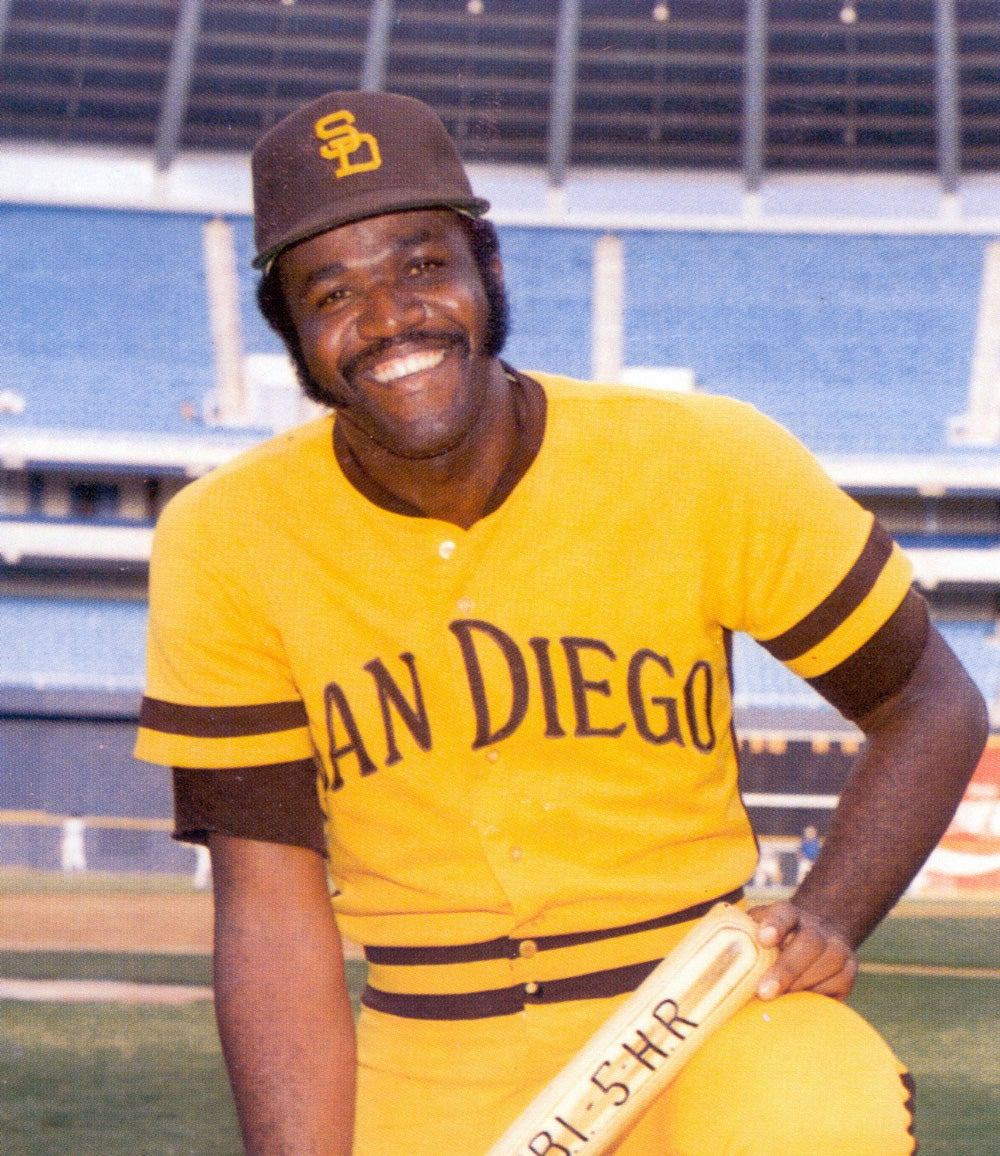

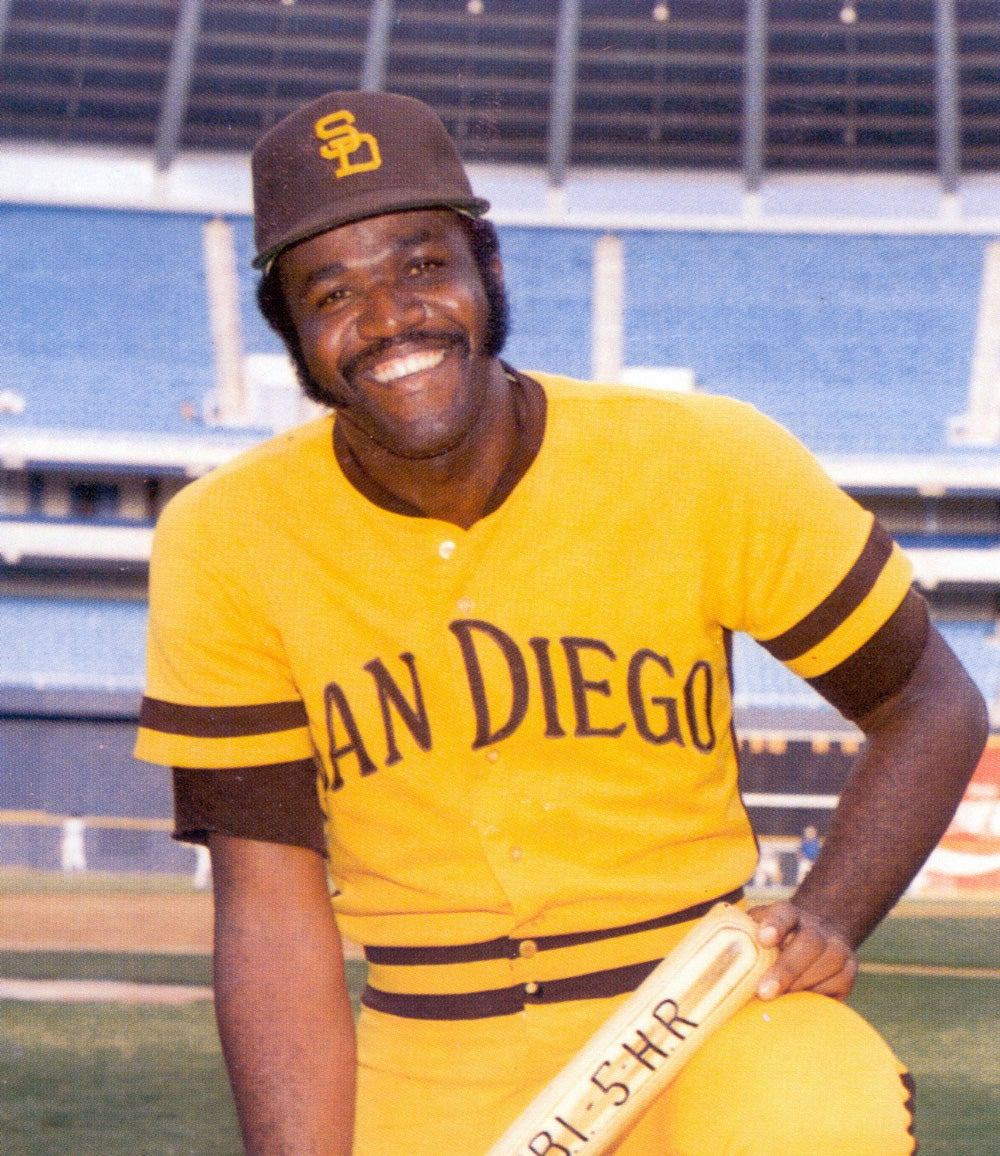

Long before he started sipping Ranger Ade, Grubb broke in with another team, one that was not known for its sports drinks, but rather for its gaudy color combination of yellow and brown. In 1971, Grubb became a member of the San Diego Padres’ organization, which drafted him in the secondary phase of the amateur draft and brought him to the big leagues the following season. Grubb’s debut came against the Atlanta Braves and basketball-sized right-hander Ron Reed. In three plate appearances, Grubb drew a walk and reached on an infield single, making for a better-than-average debut.

That was one of seven games that Grubb played for the Padres in 1972. The seven-game cup of coffee produced a .333 batting average, impressive for a player with less than two full years of minor league experience. Earlier in 1972, Grubb had irritated his minor league manager, future Hall of Famer Duke Snider, by punting his helmet into the stands! Snider was not thrilled, and scolded Grubb so forcefully that the young outfielder quickly learned the importance of curbing his temper.

With his temper in check, the likeable Grubb moved into a more significant role for the Padres in 1973. The Padres made him their platoon center fielder, where he alternated with Jerry Morales, and allotted him regular playing time against right-handed pitching. Although Grubb was not an ideal defender in center field, he did put up good offensive numbers: a .311 batting average, an on-base percentage of over .370, and an OPS of .818. With good bat speed, low strikeout totals, and a willingness to take pitches, Grubb looked like would become a lynchpin for the Padres over the next decade.

The Padres’ brass liked Grubb’s character, too. He had the kind of attitude and work ethic that made him welcome in any big league clubhouse. His mild-mannered nature made him well-liked among teammates. Tall, lean, and good looking, he often wore glasses (as he did on his 1983 Fleer card). Generally speaking, Grubb’s physical characteristics and manner reminded some of Clark Kent, the alter ego of Superman.

After his fine full-season debut of 1973, Grubb remained an effective role player for the Padres. In 1974, he became witness to one of the strangest events in the game’s history. As the Padres played their Opening Night game at San Diego Stadium, the team’s new owner, Ray Kroc, took to the public address microphone. Kroc berated the performance of his new Padres. “I’ve never seen such stupid ballplaying in my life,” Kroc said, his words greeted by cheers from the San Diego fans.

As the declaration sounded from above, Grubb listened from his place on the field. “Actually, I believe that I was on deck and suddenly I heard this voice come over, it sounded like God,” Grubb told me several years ago during a visit to Cooperstown. “He was getting on us and apologizing to the fans. He was not going to put up with this type of baseball.”

Grubb claims the Kroc announcement did not upset the players all that much. “I think the players [actually] appreciated it because we were playing pretty bad at the time. … It showed that there was an owner there who cared a lot and was not going to put up with poor baseball.”

In contrast to the Padres, Grubb played well, making the All-Star team that summer. After another good season in 1975, he made the transition to left field in ’76, but played in only 109 games due to an injury that knocked him out of the lineup for all of May and part of June.

While Grubb had shown himself to be a competent player, he had little power and had played mostly against right-handed pitching. Could hit he left-handers? That remained unknown. At the 1976 Winter Meetings, the Padres showed a willingness to discuss trades for Grubb. At one point, they talked to the Cleveland Indians about the availability of their young outfielder George Hendrick. Seeing a chance to upgrade their outfield, the Padres packaged Grubb with defensive-minded catcher Fred Kendall and utility infielder Hector Torres, sending the trio to the Indians for Hendrick.

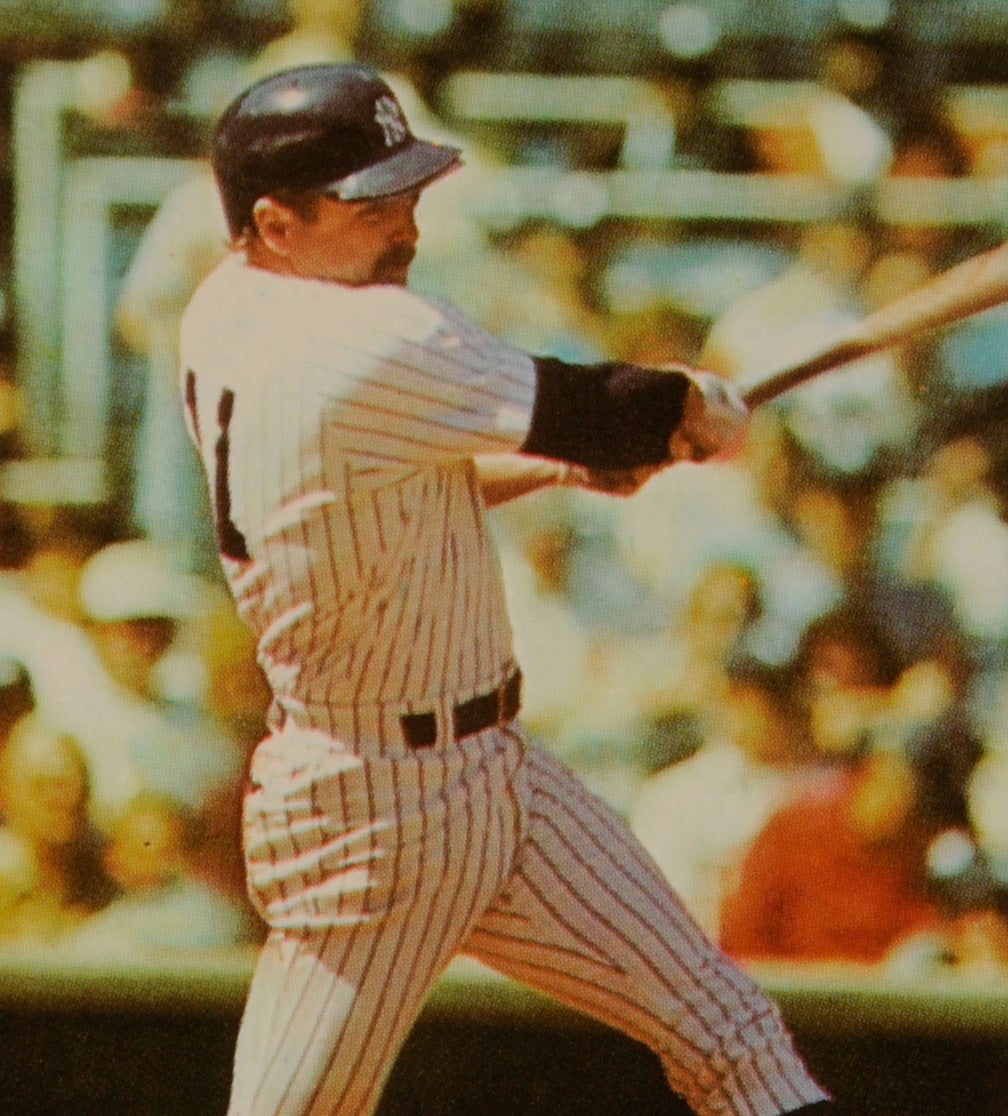

In 2009, Johnny Grubb participated in the first Hall of Fame Classic in Cooperstown. PASTIME (Milo Stewart Jr. / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Though he had never before seen American League pitching (in an era before interleague play), Grubb had no trouble at all in making the transition. In fact, he hit better than ever, putting up a .301 batting average and a .425 on-bae percentage in his first 34 games. With Grubb perhaps headed toward his best season, he checked his swing awkwardly while facing Gaylord Perry, resulting in what the Indians believed to be a pinched nerve. The injury healed so slowly that the Indians decided to take a second look. An X-ray showed something completely different: a fracture of the hand. Thanks to the freak injury, Grubb’s productive season came to an end, with his last game played coming on July 7.

Missing the balance of the 1977 season, Grubb returned to health in 1978 and showcased a different kind of game. His batting average dropped into the .260s, but he showed major league power for the first time. Having never hit more than eight home runs in a season, Grubb powered 14 home runs through his first 113 games in 1978. Strangely, the newfound power did not keep Grubb in Cleveland long-term. On Aug. 31, the Indians shipped Grubb to the Rangers for two players to be named later, neither of whom would have much of an impact.

Why did the Indians trade Grubb? Eligible for free agency at seasons end, Grubb had already asked for a five-year contract, something the Indians simply would not do. Unwilling to negotiate, the Indians believed they could not re-sign Grubb. A trade became the next best option. The trade angered Cleveland fans, who had come to like the 29-year-old outfielder and felt the Indians had failed to acquire true value for a quality player.

Grubb joined a Rangers team that was in the hunt for the American League West title. The Rangers hoped that the addition of Grubb would help them overtake the Kansas City Royals in the American League West. That didn’t happen, but through no fault of Grubb. Playing in 21 games down the stretch, Grubb went on a tear, batting .394 with an OPS of 1.121.

As well as he played, Grubb’s strong finish did not guarantee him a starting job with the Rangers in 1979. With a deep outfield, Grubb played only a semiregular role, filling in at all three outfield spots. Grubb once again proved productive, hitting 10 home runs in under 300 at-bats and stringing together a 21-game hitting streak at one juncture. If only he had more playing time.

The following season, Grubb expressed frustration over his role with the Rangers, whose crowded outfield featured Al Oliver, Mickey Rivers, Billy Sample, Rusty Staub, and Richie Zisk. Normally quiet and easy going, Grubb butted heads with manager Pat Corrales, his onetime teammate with the Padres back in the early 1970s. The situation became so troublesome that Grubb demanded a trade. Given Grubb’s generally agreeable demeanor, the demand for a trade caught the Rangers by surprise.

After the season, the Rangers fired Corrales, replacing him with Don Zimmer. Grubb and Zimmer had a good history, with Grubb having played for “Popeye” with the Padres.

Unfortunately, Grubb continued to play virtually the same role for the Rangers. He struggled at the plate during the strike-shortened season of 1981, and then hit better in 1982, but appeared in only 103 games.

Injuries and illness did not help matters. In 1981, a circulatory problem resulted in the surgical removal of one of his ribs. Grubb spent significant time on the disabled list, one of nine times that he was placed on the DL during his career.

Grubb was no longer a young player on the rise. Now 33 and with his skills in obvious decline, the trade market beckoned. During the spring of 1983, the Rangers sent Grubb to the Detroit Tigers for righty reliever Dave Tobik.

Like the Rangers, the Tigers had an overload of good outfielders, but Grubb accepted the role. Playing as a fifth outfielder, he received occasional starts against right-handed pitching. In 134 at-bats, Grubb put up an on-base percentage of .388, a terrific number that actually ranked higher than every member of the Tigers’ starting lineup.

Now that he had gained the confidence of manager Sparky Anderson, Grubb took on an expanded role in 1984. Playing the outfield corners and doing some DHing, Grubb raised his on-base percentage to .395 and clubbed eight home runs.

Playing for a good team seemed to energize Grubb. For the first time in his career, he received a shot at Postseason play. In Game 2 of the American League Championship Series, Anderson gave him a start and watched him deliver a crucial two-run double against Kansas City’s Dan Quisenberry in the 11th inning. Grubb’s dramatic double gave the Tigers a 5-3 win over the Royals.

Grubb didn’t enjoy similar heroics in the World Series, as Anderson restricted him to pinch-hitting duties. Ever the professional hitter, he did reach base twice in four plate appearances, as the Tigers rolled over the Padres, Grubb’s original team, to win the title. After 13 years in the major leagues, Grubb had earned himself a World Series ring.

Grubb was not as productive in 1985, and his falloff coincided with the Tigers’ decline from a world championship team to a third-place finish in the American League East. At 36, it appeared that Grubb was near the end of his career. Then, without warning, came the bust-out campaign of 1986. Coming to bat 210 times, Grubb batted .333 and clubbed 13 home runs.

After the high point of 1986, Grubb suffered a major falloff in 1987. Appearing in only 59 games, he batted a career-low .202 with only two home runs. If there was a consolation, it came through the Tigers’ performance as a team; they won the American League East and moved on to the ALCS. Once again, Grubb’s play in the Postseason overcame expectations. He played in four games, collected four hits, and batted .571.

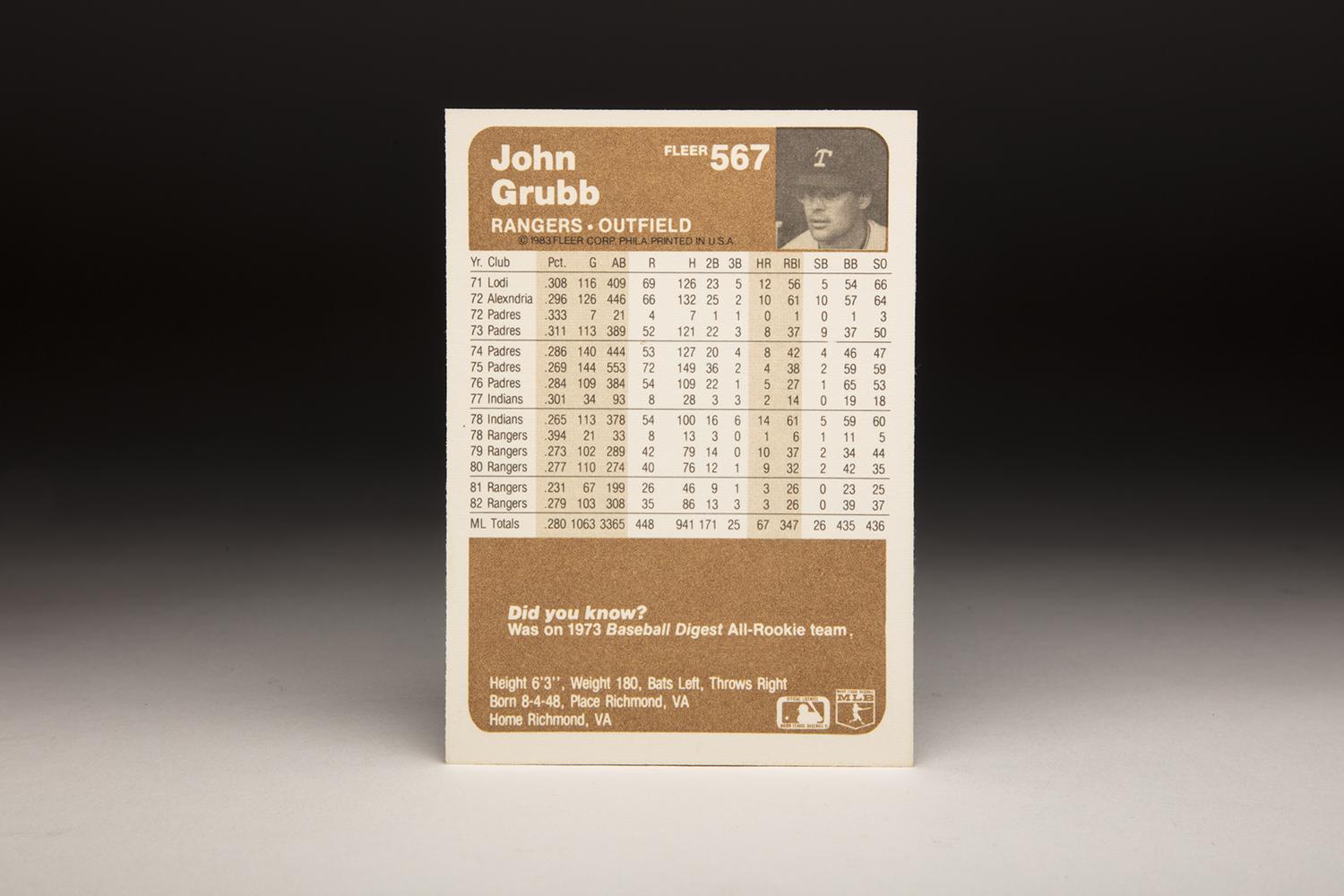

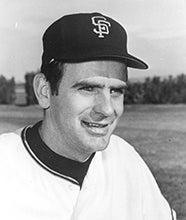

Johnny Grubb began his career with the San Diego Padres, a team he impressed with his work ethic and mild-mannered nature. PASTIME (Doug McWilliams / National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

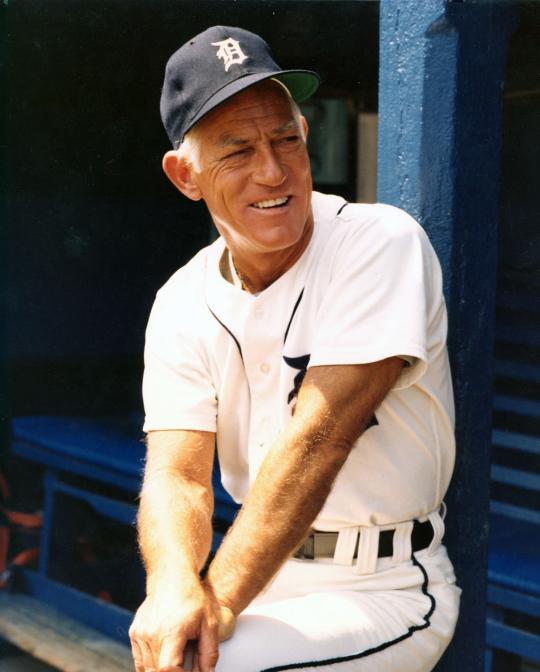

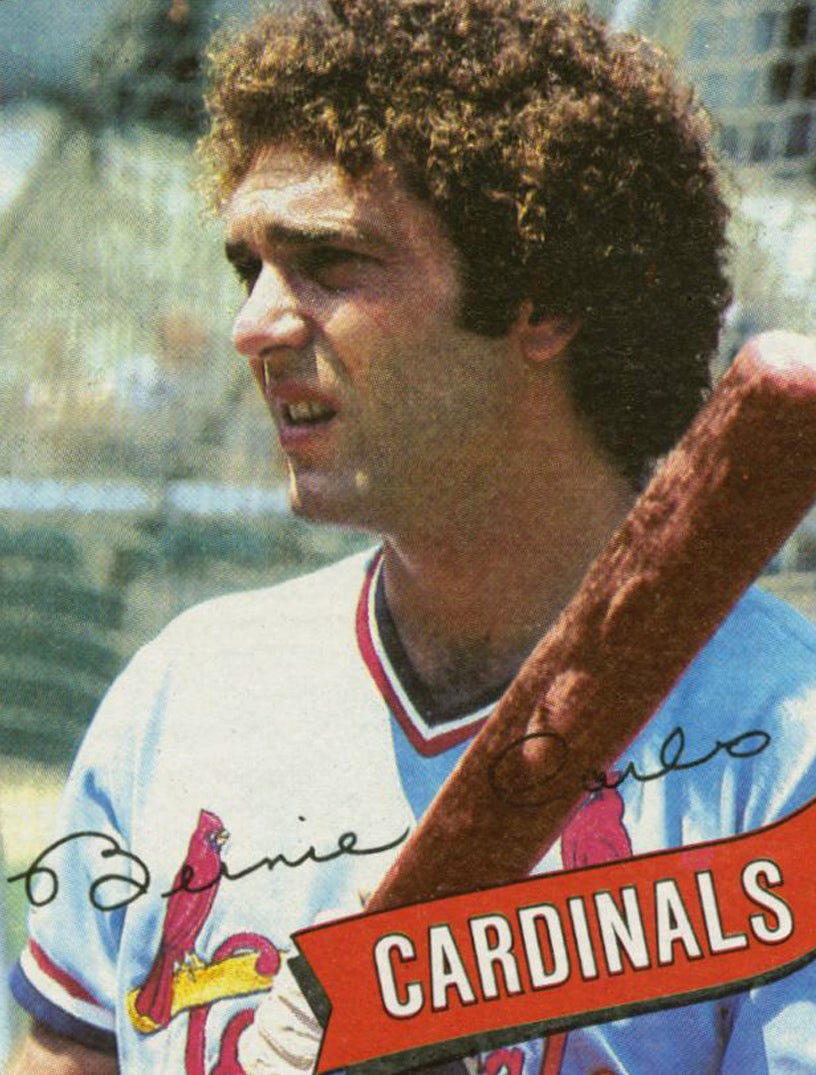

During the 1983 season, Johnny Grubb gained the confidence of future Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson, who gave Grubb an expanded outfield role in 1984. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

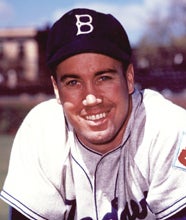

Johnny Grubb played under Don Zimmer when he played for the Padres at the beginning of his career. He would be reunited with Zimmer in 1981 when Zimmer took the helm of the Texas Rangers. PASTIME (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

His playoff performance notwithstanding, Grubb was now 38 and coming off his worst offensive season. After the World Series, the Tigers released the 16-year veteran, bringing his career to a close.

Since his retirement, Grubb has stayed active in the game. He became a minor league hitting instructor, spent a decade as a high school coach, and then worked as a coach for the pioneering Colorado Silver Bullets, the women’s baseball team that came into prominence in the 1990s. Grubb served as the Silver Bullets’ hitting and outfield coach, filling that role for four seasons before the team lost its sponsor and was forced to fold.

Grubb has also spent a good deal of time attending fantasy camps and participating in old-timers events, usually as a representative of the Tigers. Back in 2009, he came to Cooperstown to participate in the Hall of Fame Classic. That gave me the chance to meet and interview him at Doubleday Field. Looking trim and not all that different from his playing days, Grubb was gracious and agreeable, more than happy to share some memories of playing for the Padres, Indians, Rangers, and Tigers. Given how happy and at ease he looked on his 1983 Fleer card, this should not have come as a surprise to me or anyone else.

Looking back to that day at Doubleday Field, I should have apologized for calling him “Grubb the Scrub” back in the day. Let’s take care of that apology now. Clearly, we were wrong in our childhood assessment of Johnny Grubb. When you can play 16 seasons in the major leagues, compile a .278 batting average, hit 99 home runs, and walk more often than you’ve struck out, you have done pretty well.

Johnny Grubb was no scrub. Not at all.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

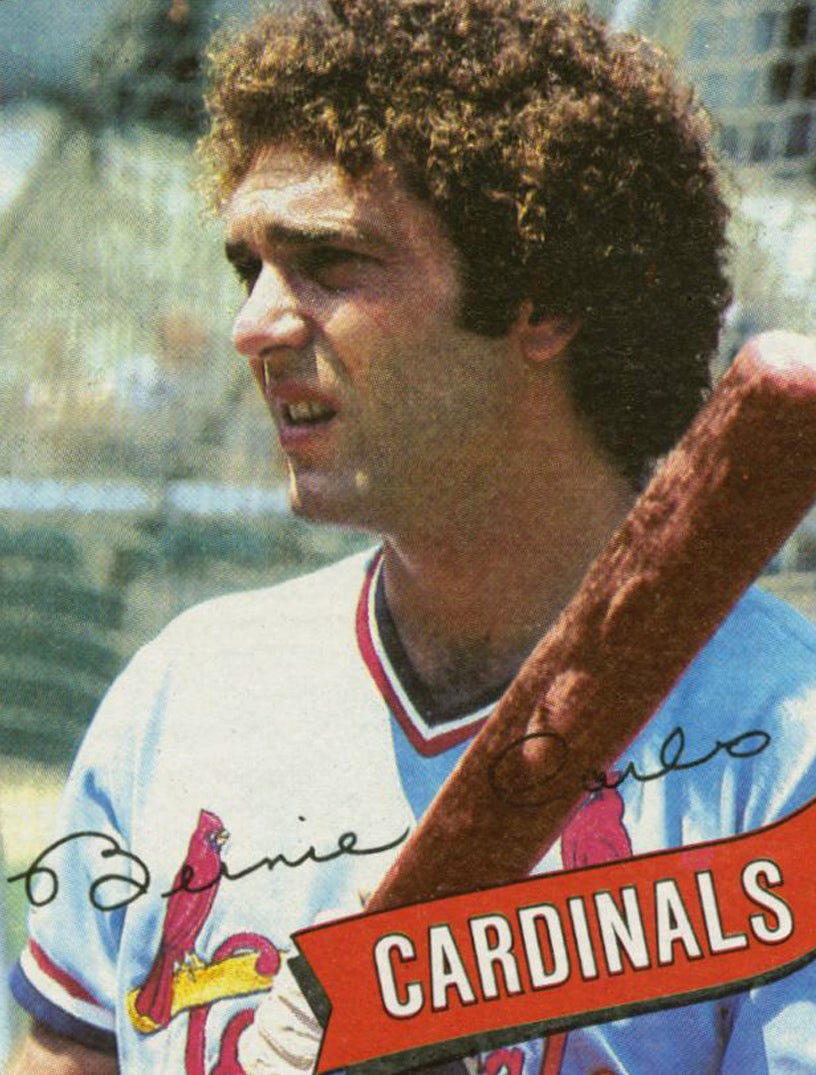

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

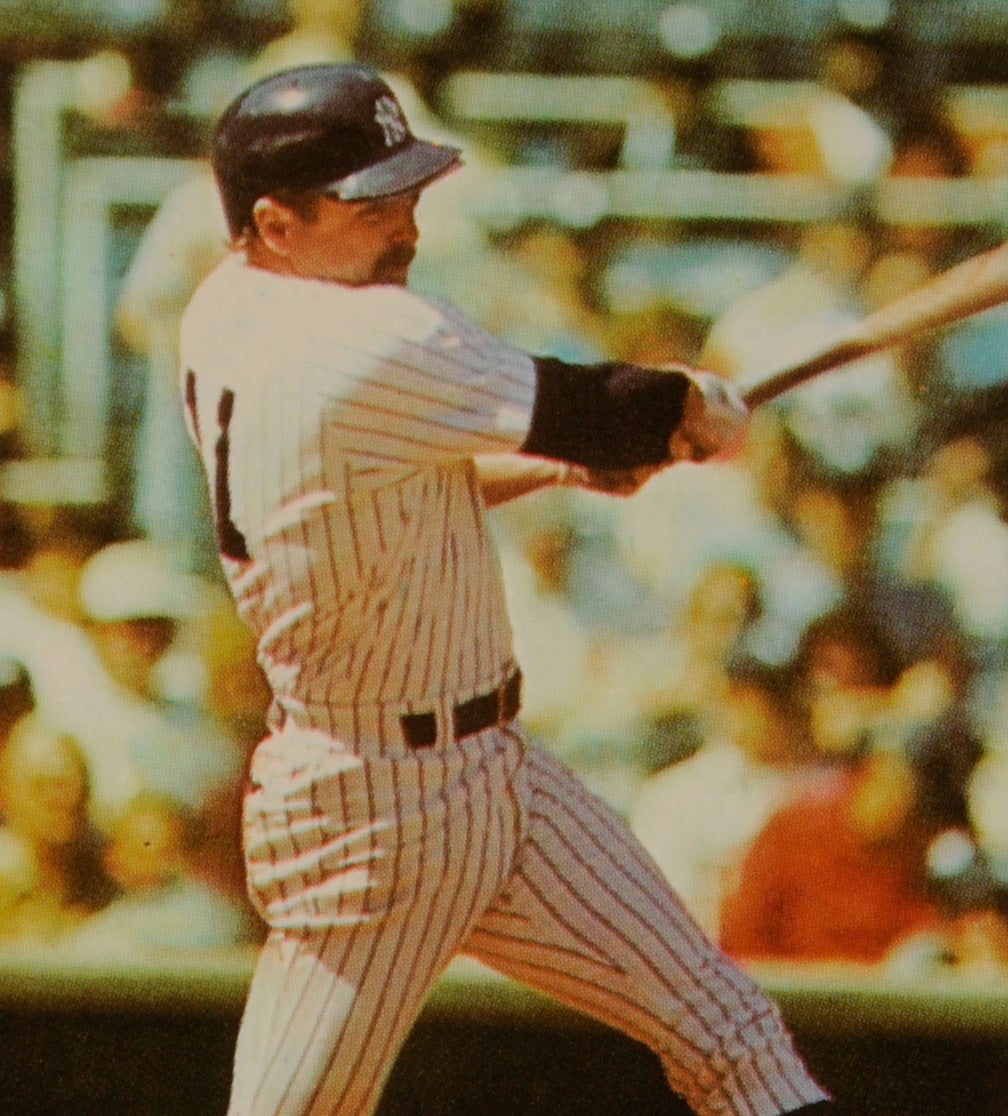

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert

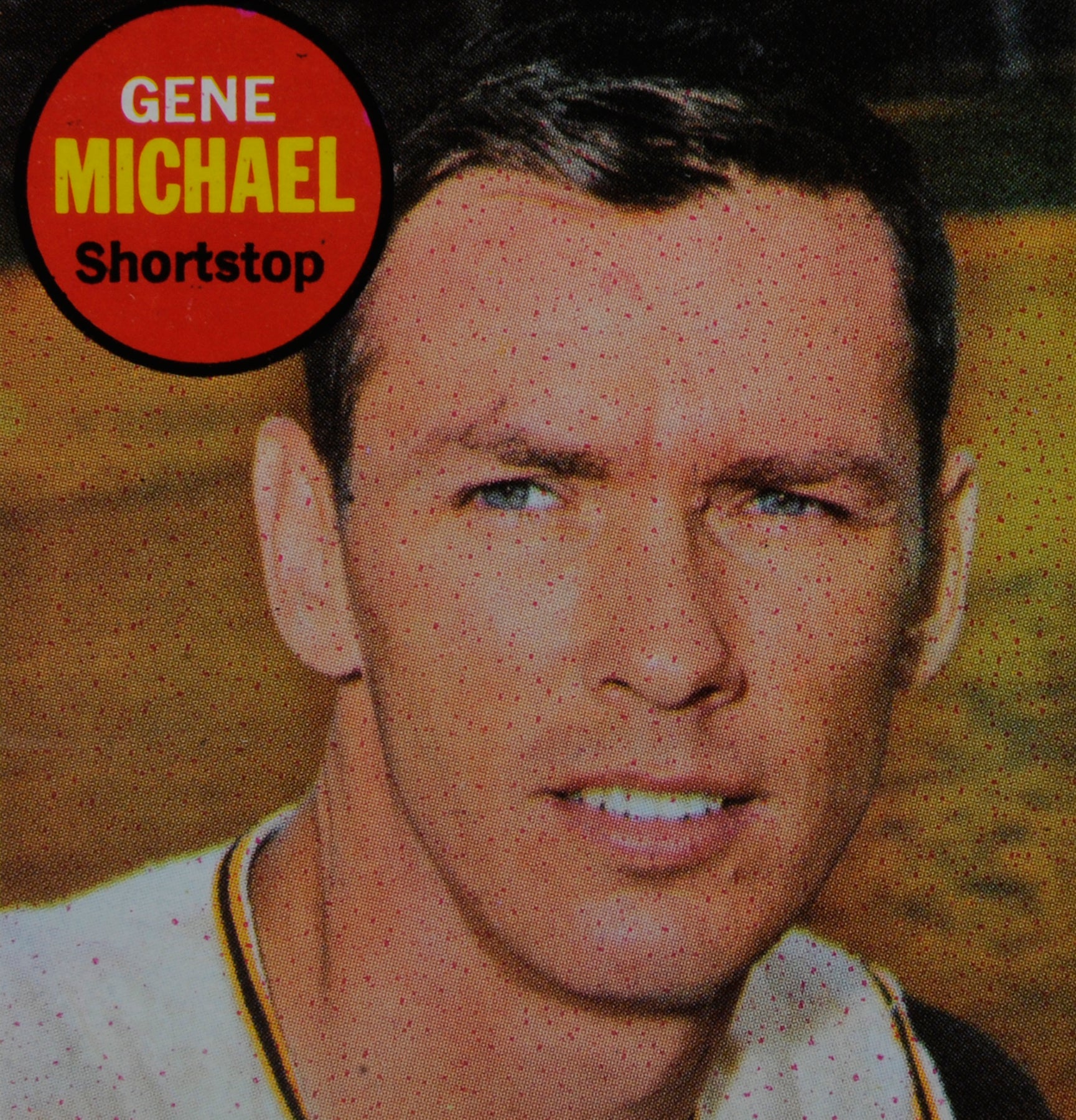

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert