- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Enrique Romo

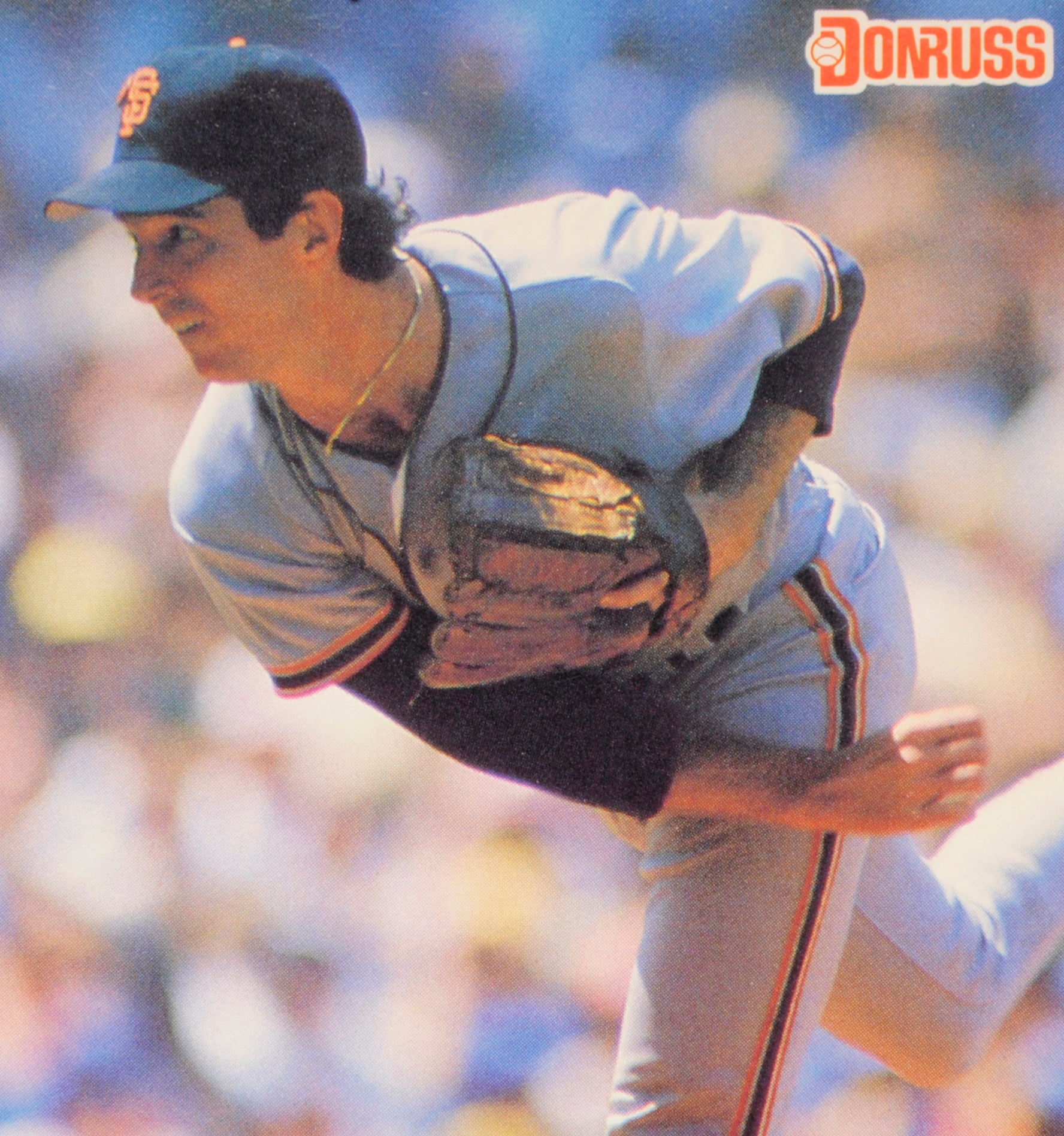

#CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Enrique Romo

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

As someone who enjoys popular culture, particularly through film and television, I often find myself comparing ballplayers on baseball cards to the actors they resemble. In the past, I’ve written about the uncanny resemblance between 1960s star Johnny Callison and actor Edward Winter, a regular guest star on M*A*S*H. I’ve also written about the similar facial features of manager Frank Lucchesi and character actor Roberto Loggia of Scarface fame.

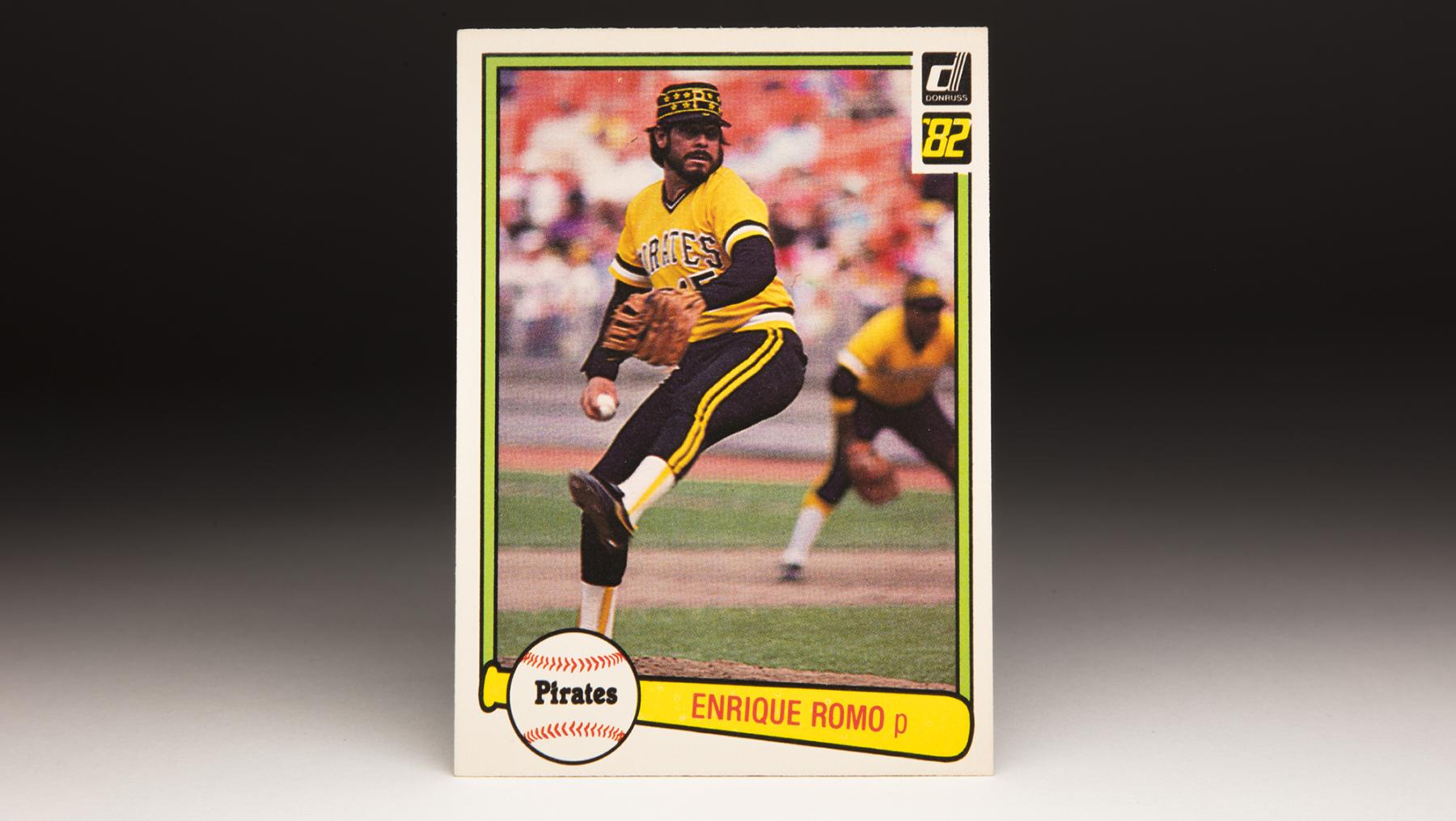

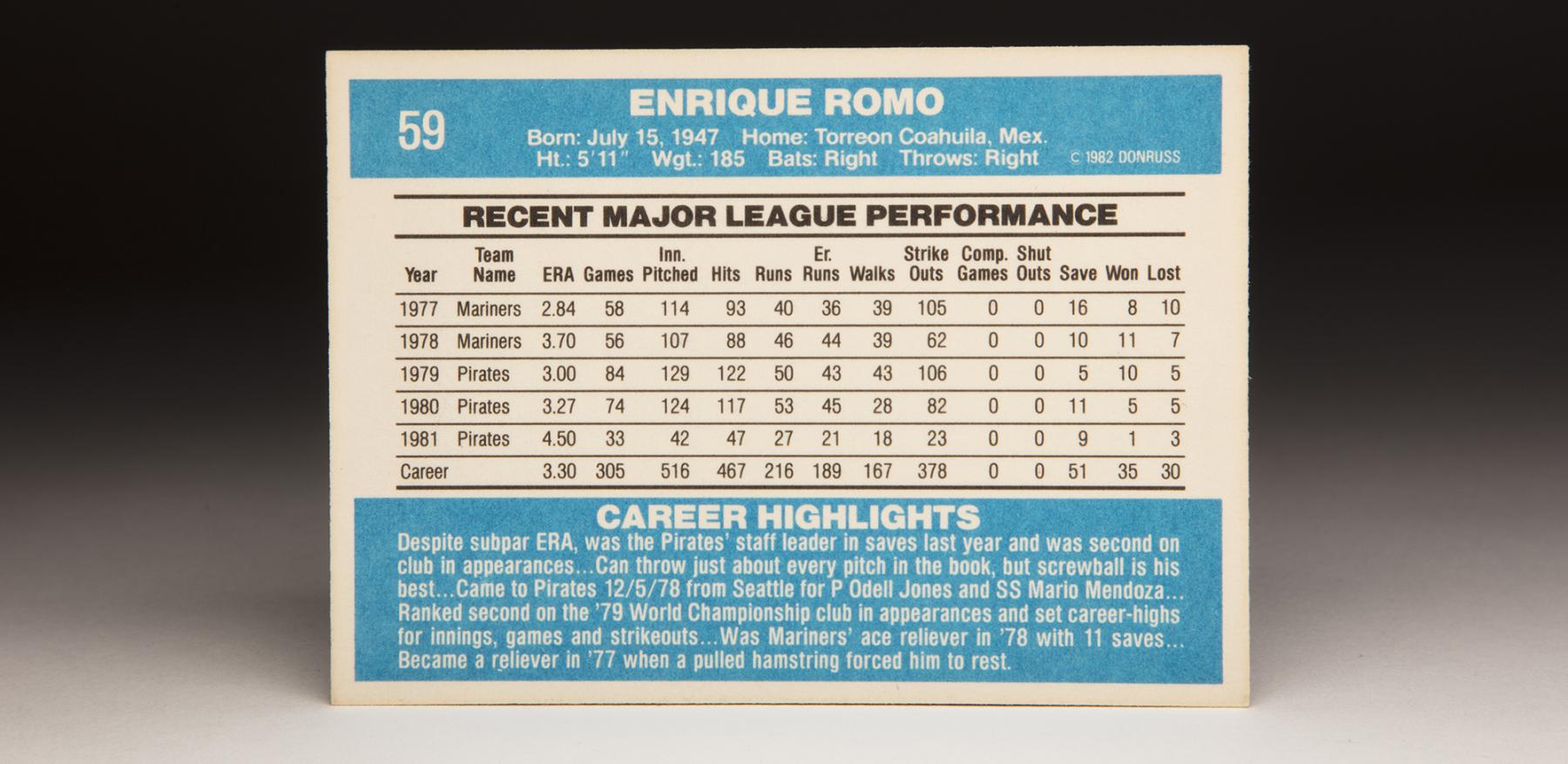

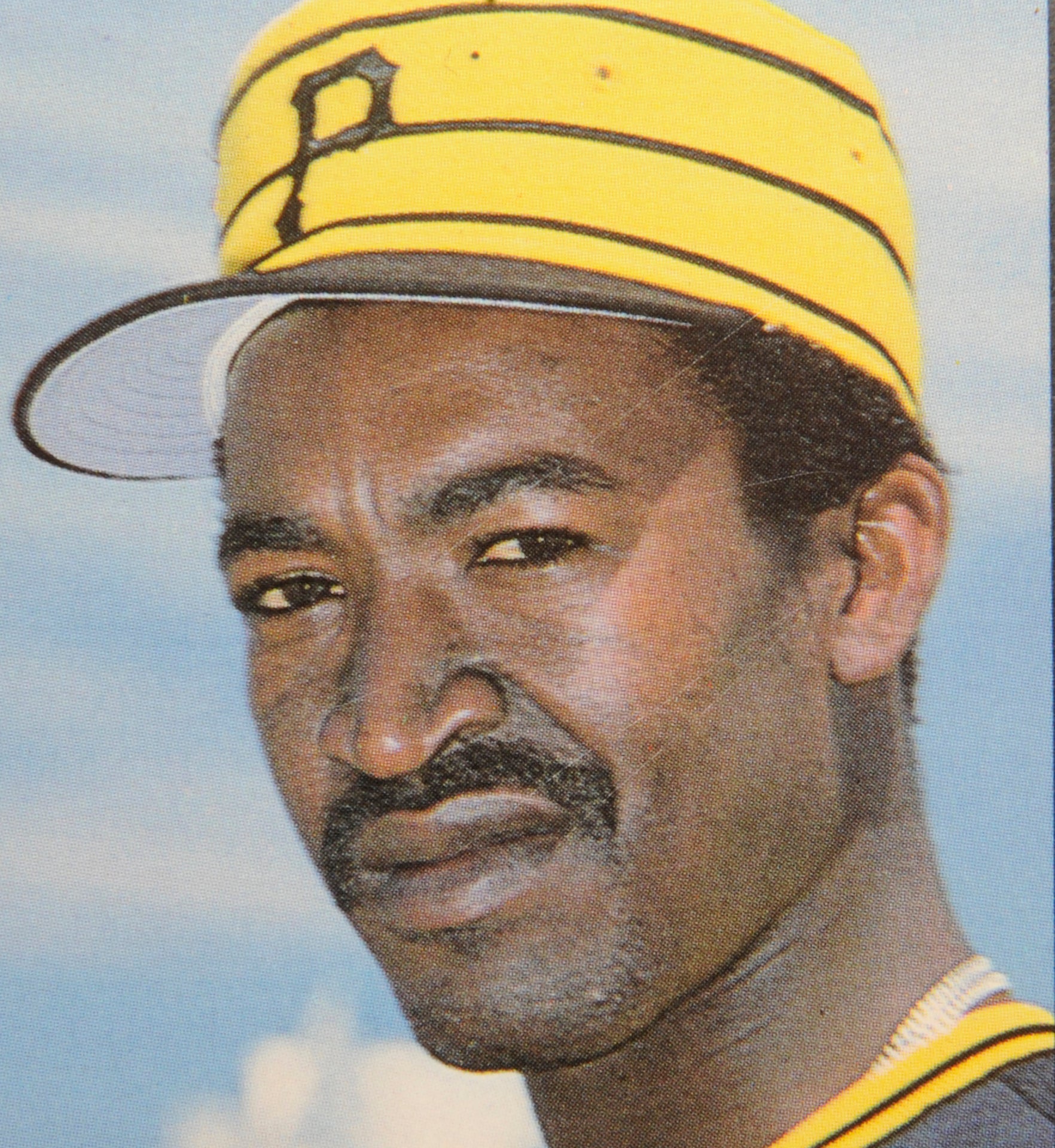

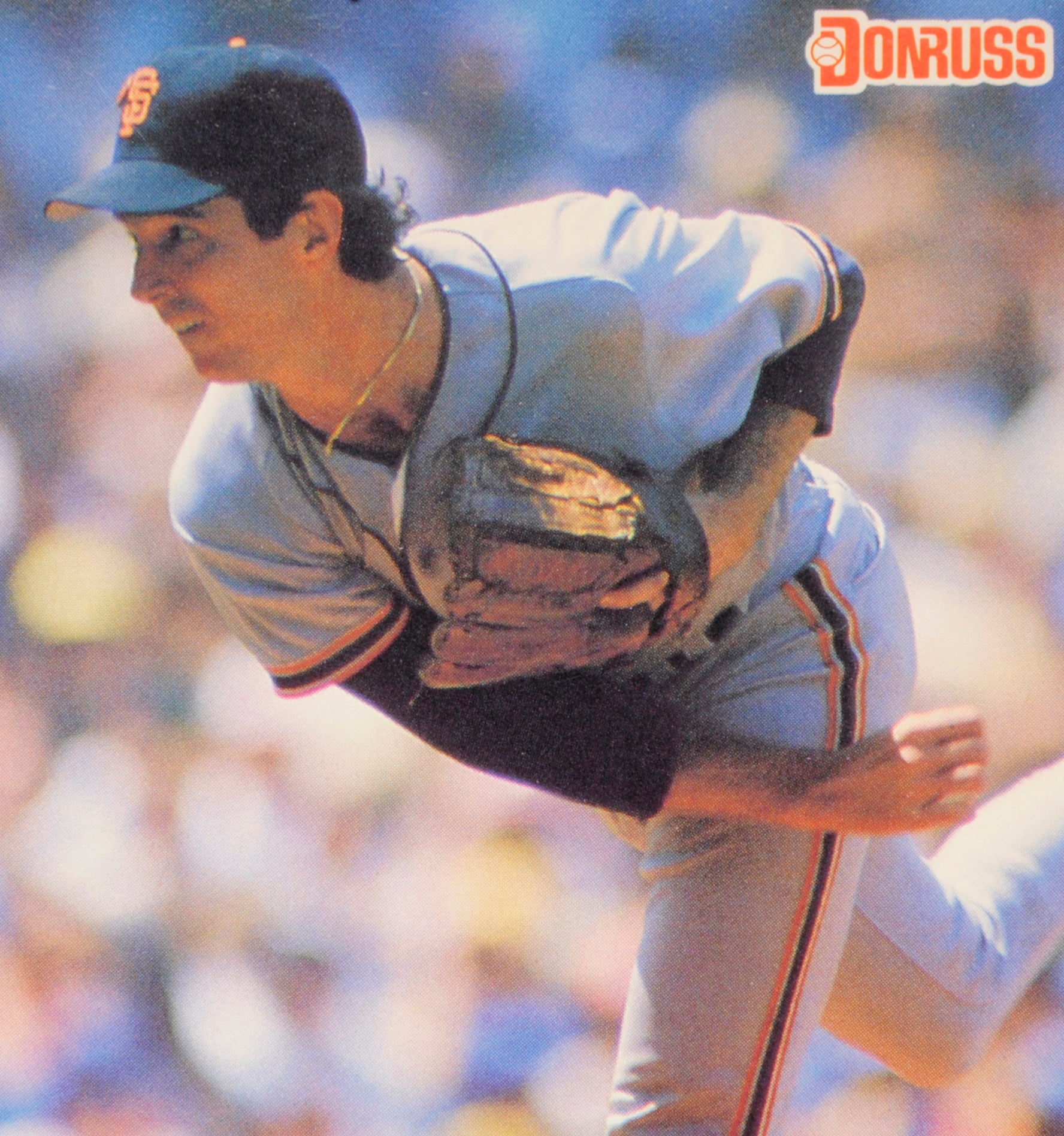

I have a similar reaction when I see old cards of well-traveled reliever Enrique Romo, a native of Mexico. On his 1982 Donruss card (and on some other selections), he often reminds me of Puerto Rican actor Luis Guzman. Though not a household name, Guzman is an excellent and prolific character actor who began playing villainous types in the 1980s but didn’t really start to earn national recognition until his appearances in such 1990s films as Carlito’s Way and Boogie Nights.

It’s not that Romo and Guzman could pass as twins – they do have some distinct physical features from each other – but they do share some common traits, too. In addition to both being of Latino descent, they have similar facial hair, both in terms of mustache and corresponding goatee. They both have stocky builds; Guzman is listed at 5-foot-7, while Romo is listed at 5-foot-10 on most of his cards.

Perhaps the one significant or telling difference is their hair: Guzman seems to wear relatively short hair for his roles, while Romo became known for letting his hair grow past his ears and rest on the tops of his shoulders.

Romo and Guzman share something else in common: Neither is what you would call a household name or a star. Guzman is a highly capable character actor, while Romo filled a role that might be compared to that of a character actor: the unglamorous role of pitching in middle relief. Romo only occasionally received opportunities to close out games and earn the glory that comes with being a closer, but he was quietly effective, at least for a few years, with the Seattle Mariners and Pittsburgh Pirates. Perhaps you could, with some degree of accuracy, call Romo the Luis Guzman of relief pitchers. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

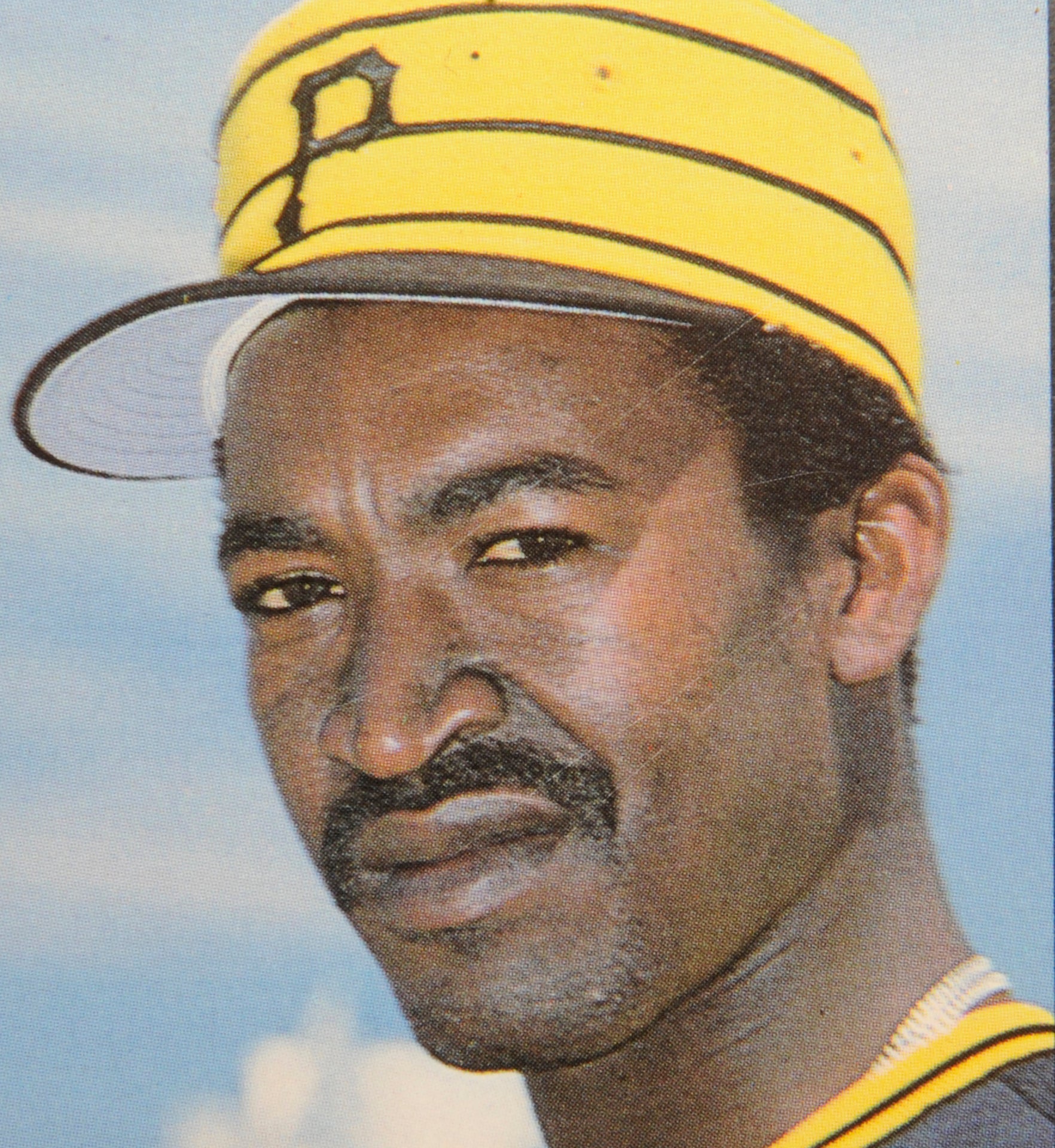

Romo’s 1982 Donruss card not only stirs up thoughts of his doppelganger actor, but also includes a second player, whose blurry figure appears in the background. That is indeed Willie Stargell playing first base, during a game at Shea Stadium in 1981. Both Stargell and Romo are showcasing the gaudy colors that gave the Pirates such an indelible look in the early 1980s. In assembling those bumblebee uniforms, the Pirates mixed and matched a variety of tops and pants, but no combination was more emblematic of the look than what we see on the Donruss card: the bright gold jersey and the skin-tight black pants.

It’s hard to imagine that many of the Pirates players enjoyed wearing these lurid outfits—especially the players with less than ideal builds – but these uniforms still have a cult following today, to the point that the Pirates still wear these throwbacks for Sunday home games.

With his thick build, long hair, and ever-present goatee, Romo was certainly one of the most recognizable of the Pirates in the early 1980s, even though he was overshadowed by the team’s larger stars, players like Willie Stargell, Bill Madlock and John Candelaria. But in his earlier professional career, Romo was a full-fledged star in his native Mexico.

After a stint with the Mexican Navy, Romo began his professional career in a lower-level Mexican league in 1966. Two years later, he moved up to the country’s top league, known simply as the Mexican League. Eventually becoming a top-flight starter with the Mexico City Reds, Romo won a total of 109 games over four seasons. Romo and the Reds captured three league titles during that run.

The 1976 season represented the peak of Romo’s career in the Mexican League. That summer, he added a screwball to his repertoire; the pitch made him more effective against left-handed hitters and allowed him to lower his ERA to 1.89 while he won 20 games against only four losses. Romo became so dominant in Mexico that some skeptics claimed he was doctoring the ball, a claim that he denied.

Romo’s stellar season in Mexico City caught the eye of Lou Gorman, the first general manager of the fledgling Seattle Mariners. Gorman happened to be friends with Angel Vazquez, the principal owner of the Mexico City franchise. Gorman and Vazquez worked out a deal, with the Mariners paying only $75,000 to acquire Romo’s contract.

The younger brother of big league right-hander Vicente Romo, Enrique reported to the Mariners’ inaugural training camp in the spring of 1977. Romo did not speak much English, but the presence of fellow Latino teammates like Diego Segui and Jose Baez provided some comfort.

Despite reporting late because of an immigration delay, and despite being bothered by a hamstring pull, the 29-year-old Romo made the Mariners’ Opening Day roster as the No. 2 starter behind the ageless Segui. Romo made three starts before aggravating the hamstring injury, forcing the Mariners to place him on the disabled list.

Upon his return to the active roster, Romo moved to the bullpen. Using his deceptive mix of screwball, forkball, slider, curve, and fastball (and possibly a spitball), he became manager Darrell Johnson’s most trusted reliever. Johnson called on him 55 times, and Romo responded by lowering his season ERA to 2.83 and recording 16 saves. In an interview with the Sporting News, Johnson said: “Enrique Romo is the best reliever in the American League.”

Romo also blended well in the Mariners’ clubhouse. Despite his lack of English, his personable nature made him welcome with Mariners teammates. The other Mariners also came to respect him because of his willingness to take the ball at all times.

As well as Romo pitched as a major league rookie, he found life more difficult in his second season, both off the field and on. In September of ’78, he was the victim of a mugging in New York City. The perpetrators sprayed mace in Romo’s face and also bruised his ribs, but Romo did not miss any significant time.

On the field, Romo endured nothing as traumatic but saw his ERA rise to 3.69, in part because American League hitters became more familiar with him and in part because of the Mariners’ shaky defensive play. Still, Romo won 11 games and saved 10 others, and remained Seattle’s most effective relief pitcher.

That winter, the Mariners engaged the Pirates in trade talks, with Romo’s name coming up in the conversation. The two teams came to agreement on a six-player deal that sent Romo and two younger players to the Pirates for slick-fielding shortstop Mario Mendoza, right-hander Odell Jones and a top minor league prospect. The trade hurt Romo, who felt that his job was safe in Seattle. “I was very upset and I was angry,” Romo would tell Hy Zimmerman of the Seattle Times through an interpreter. “I pitched for Seattle [for] two seasons and I wanted to stay there.”

Romo’s early weeks with the Pirates did not go well. He struggled at the outset of the 1979 season, perhaps because of the cold weather in Pittsburgh, as opposed to the neutral weather conditions of pitching at the Kingdome in Seattle. Those early struggles created some tension between Romo and Pirates fans; Romo came to regard the fans in Pittsburgh as more demanding than the even-keeled fan base in Seattle.

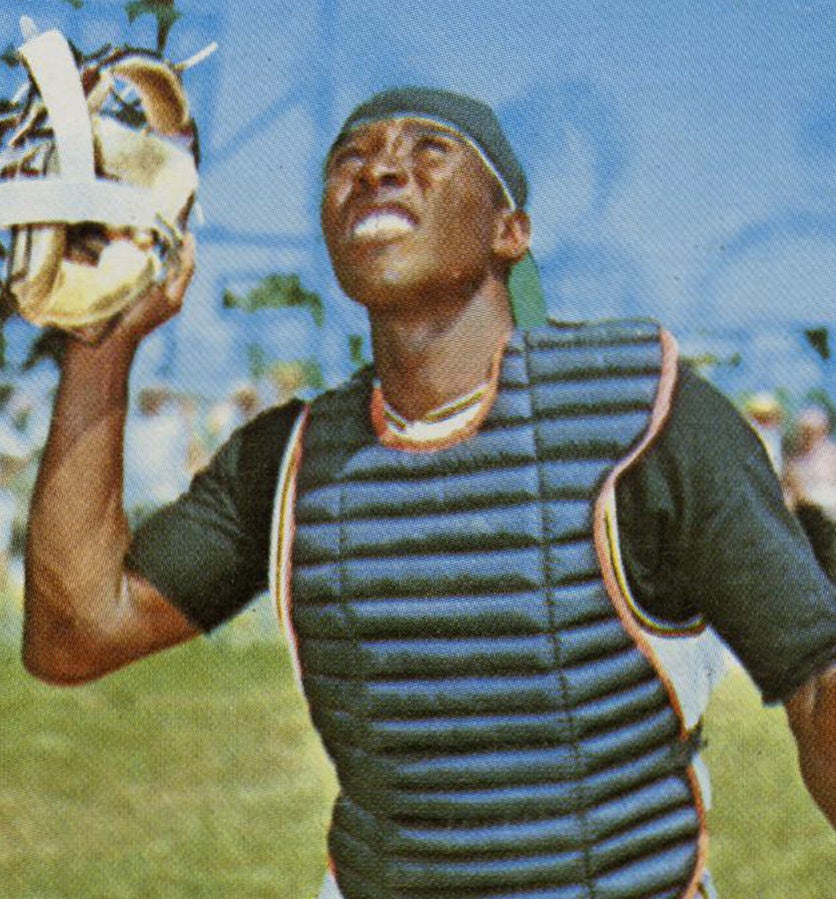

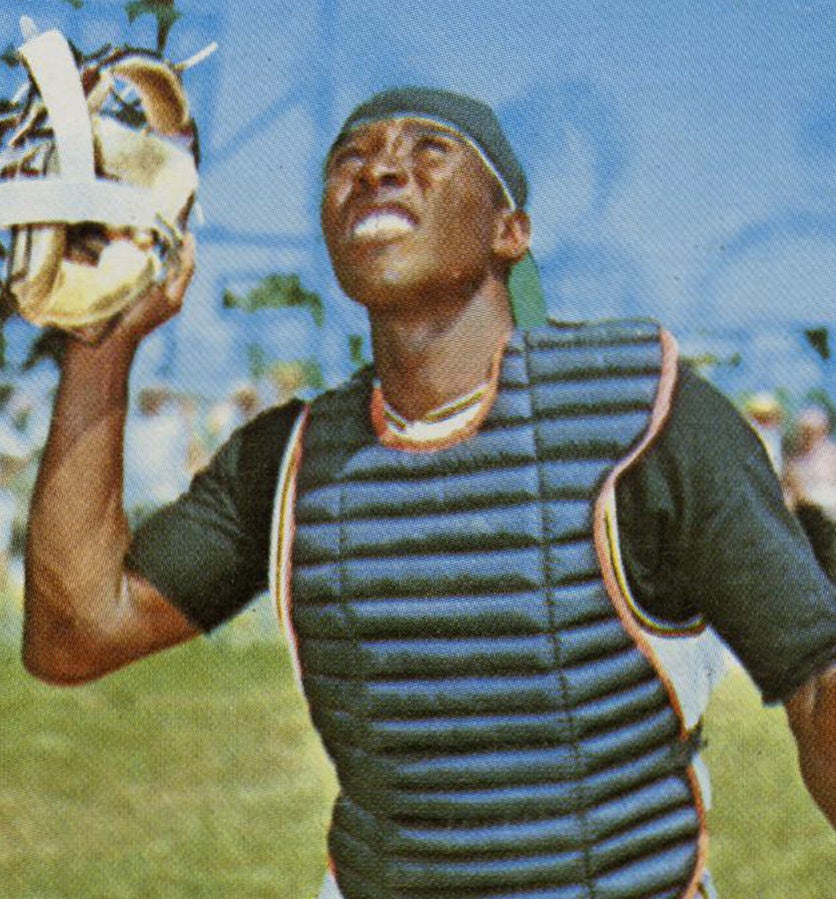

Romo’s struggles with speaking English also prevented him from socializing with many of his teammates. One exception was veteran catcher, Manny Sanguillen, a native of Panama who became fast friends with Romo.

After a poor start with Pittsburgh, Romo settled down to pitch brilliantly for much of the ’79 season. By the end of the regular season, he appeared in 84 games, logged 129 innings, and shaved his ERA to 2.99. Along with veterans Kent Tekulve and Grant Jackson, Romo became a vital part of a deep Bucs’ bullpen that played a major role in the team winning the National League East.

Romo would falter in the NLCS and World Series to such an extent that manager Chuck Tanner did not use him in the final four games of the Fall Classic. Once again, the cold weather of the Northeast seemed to bother Romo, whose arm was already sore from overuse that season. As Romo would tell the Pittsburgh Press later on, “I never felt the cold like I did in the World Series.” Even with his personal failings amidst the bad weather, Romo earned himself a World Series ring, as the Pirates rallied from a 3-1 deficit to defeat the favored Baltimore Orioles.

In spite of a heavy workload and a long 1979 season, Romo came back to pitch well in 1980. His ERA rose slightly, but he remained mostly effective, again logging over 120 innings. He also came to feel at home in a clubhouse known for its looseness, frequent pranks and endless ribbing. “He couldn’t believe how crazy we are,” Sanguillen told the Beaver County Times in recalling Romo’s first season in Pittsburgh. “Now, he’s one of the biggest crazies here. He fits in.”

The 1981 and ’82 seasons became more problematic for Romo, especially with the overuse of his right arm finally beginning to take a full toll. Romo spent time on the disabled list in 1981, with the condition of his arm pushing his ERA above 4.00. The 1982 season brought more struggles his way, including a conflict with Tanner. Late in the season, Tanner fined Romo $10,000. When asked about the reasons behind the discipline, Tanner said only that Romo was guilty of “breaking training.” In actuality, Tanner punished Romo for failing to show up for two late-season games.

The fine and suspension angered Romo, who remained resentful throughout the winter. When the Pirates opening up Spring Training in February, Romo told them he would be late because one of his children was ill with chicken pox. Later on, Romo admitted that had nothing to do with his refusal to report; he now told the Pirates that he had decided to play in Mexico for a team in an unsanctioned league. The Pirates informed Romo that he needed to submit a formal letter of retirement; otherwise, the Pirates would fine him $500 a day.

After Romo missed his 18th consecutive day of spring workouts, Tanner told Pittsburgh writers that he had reached his boiling point. “I don’t want him on the team,” Tanner said. “I hope we can trade him.” Finally, in the waning days of March, Romo sent the Pirates a telegram, officially informing them of his retirement. He pitched for the rebel league in Mexico until the middle of the 1986 season, when the league folded. At that time, Romo called it quits for good.

In 2003, he earned induction into the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame, a shrine that has honored other Mexican League greats like Hector Espino and Andres Mora and his brother, Vicente. In 2016, Romo added the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame to his resume.

Induction in various halls of fame has not stopped Romo from playing baseball at the semi-pro level; he continues to pitch in senior leagues, even though he is now in his sixties. In one of those senior or “master” games, he faced his brother Vicente. The two brothers did appear in the same major league game, back on June 2, 1982, but they did not directly face each other as pitcher and batter that night.

While Romo has gained a level of fame in Mexico, he remains something of a mystery man in the United States. To this day, Romo has never explained the full reasoning behind his decision not to attend Spring Training and simultaneously give up a job in the major leagues. Additionally, he has never attended a reunion or autograph show for the 1979 Pirates, despite the many gatherings the team has had over the past four decades. No recent photos of Romo seem to be available on the Internet, either, which only adds to the level of obscurity.

I imagine that Romo looks quite a bit different these days. It’s quite possible that he looks nothing like Luis Guzman anymore. But I always think of Romo when I see Guzman in one of his movie roles. Those card images of Romo wearing the bumblebee uniform come immediately to mind. If Hollywood ever makes a film about the 1979 Pirates, I’ll have a pretty good suggestion on who might play the role of the mysterious Enrique Romo.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Mike Krukow

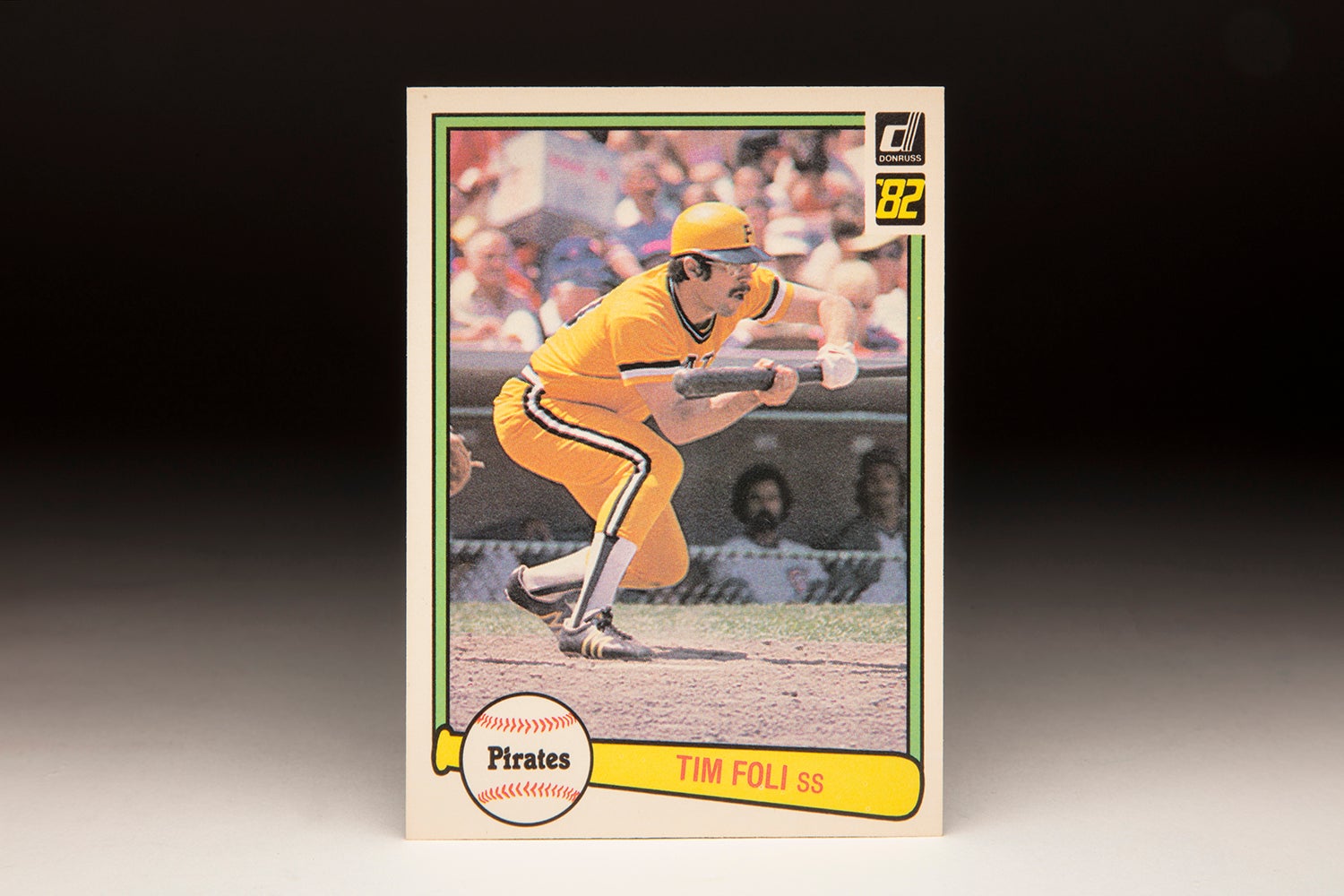

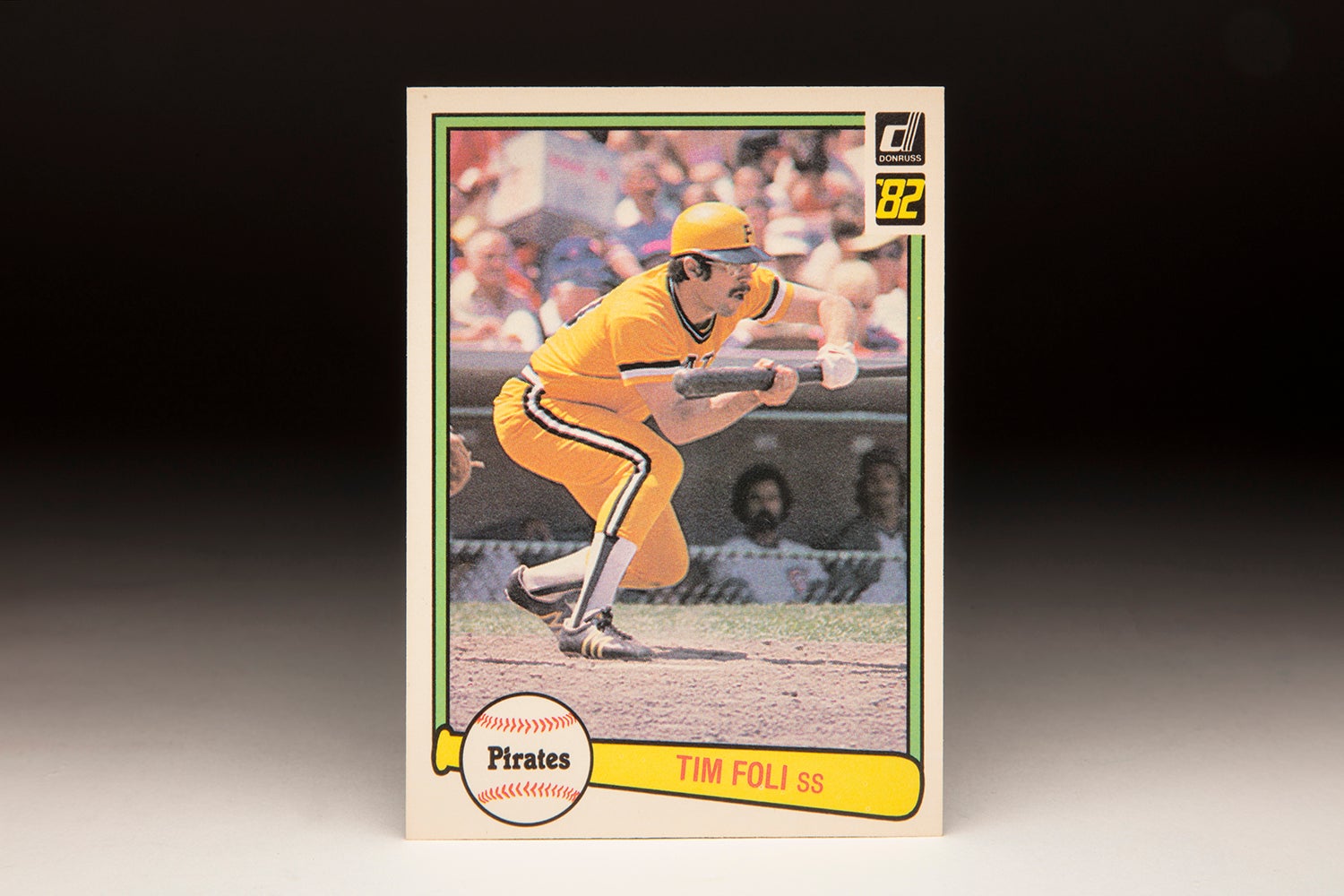

#CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Tim Foli

#CardCorner: 1968 Topps Manny Sanguillen

#Card Corner: 1983 Donruss Cecilio Guante

#CardCorner: 1987 Donruss Mike Krukow

#CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Tim Foli