- Home

- Our Stories

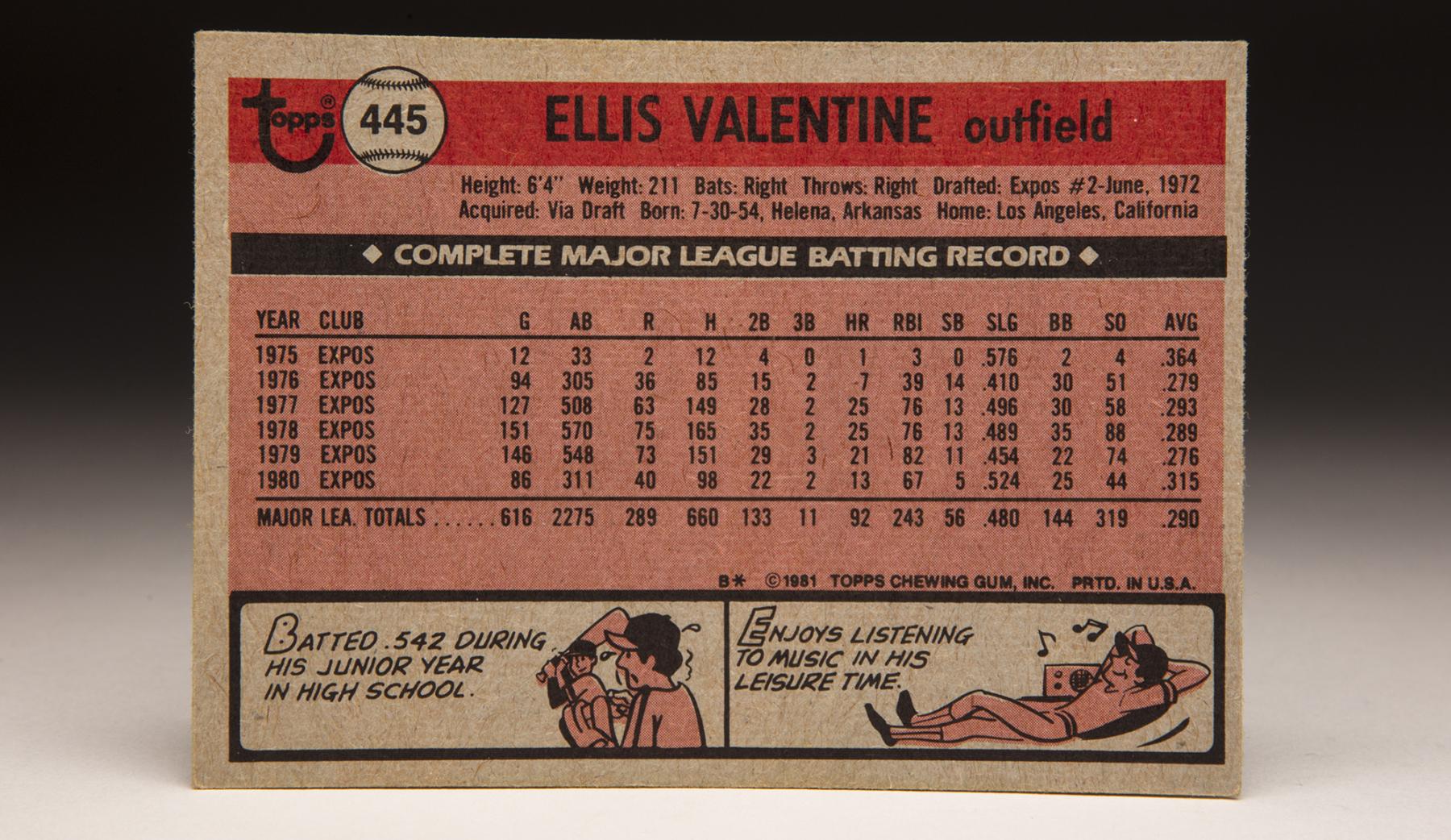

- #CardCorner: 1981 Topps Ellis Valentine

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Ellis Valentine

Ellis Valentine’s prodigious on-field talent brought him to the big leagues, and his struggles off it truncated one of the most promising careers of the late 1970s.

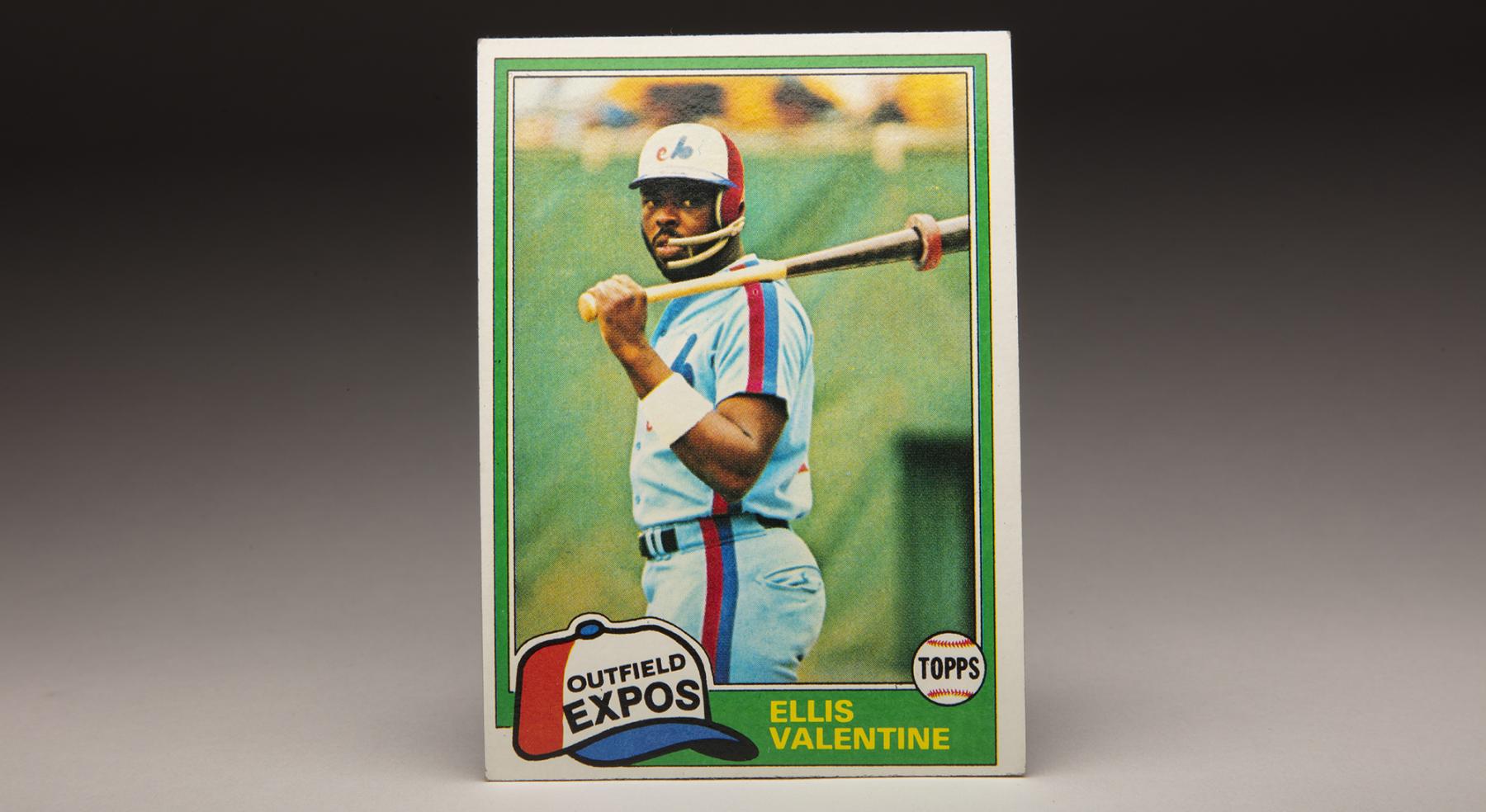

That has always been his legacy. But thanks to the proliferation of the new “face flap” batting helmets – and the indelible impression of Valentine’s 1981 Topps card – the former prized prospect of the Expos can add the word “trailblazer” to his resume.

Valentine is captured on the card in the on-deck circle of a visiting ballpark – perhaps Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium – during the second half of the 1980 season. He is sporting half of what looks like a football player’s facemask, covering his left cheek.

The mask is to protect Valentine from a repeat of what happened on May 30 of that year in St. Louis. Batting cleanup for the Expos in a game where he already tallied a three-run double (misplayed in left field by the Cardinals’ Ted Simmons, who was usually a catcher) and a walk, Valentine was hit the face by a pitch from Cardinals’ reliever Roy Thomas.

“(Home plate umpire Satch) Davidson said the ball went off Ellie’s hand or wrist and hit him on the face,” Expos manager Dick Williams told the Montreal Gazette after the game. Valentine was admitted to a St. Louis hospital and was diagnosed with multiple facial fractures and a concussion. He was out of action until July 10 – and admitted later that he was never the same player after the beaning.

Valentine was not the first player to wear a mask at bat – Dave Parker of the Pirates experimented with football facemasks and even a hockey goalie mask in 1978 after a home-plate collision with Mets catcher John Stearns – but it was a rare sight during his era.

Today, players throughout the big leagues are wearing flaps designed to protect the leading edge of their face in a time when pitchers routinely touch the 95-mph mark and beyond.

The 1980 season proved to be the last truly productive season in Valentine’s 10-year career. Despite the injury, he hit .315 in 86 games, with 13 home runs and 67 RBI. But his off-the-field struggles with substance abuse led the Expos to trade him to the Mets early in the 1981 season. By the end of the 1985 campaign, Valentine was out of baseball.

It was a precipitous drop for a player widely regarded as one of the most talented in the game when he debuted with the Expos in 1975. Montreal’s late 1970s outfield of Warren Cromartie in left, Andre Dawson in center and Valentine in right was considered state of the art – with Dawson thought to be the one who would take the most time to develop.

By 1984, neither Cromartie nor Valentine were in the major leagues. Dawson, meanwhile, was headed to the Hall of Fame.

Valentine did earn an All-Star Game berth in 1977 and a Gold Glove Award in 1978, a year when he had an other-worldly 24 assists in right field. Still, most who saw him as a youngster lamented that his potential was never fulfilled.

Valentine has spent much of his post-playing career counseling others – cautioning them not to make the mistakes that he did. It was his way of giving back to the game.

But whether he knew it or not, his equipment choices illustrated by a Topps baseball card may have changed the game forever – and will ultimately save many players from the pain he endured on that Friday night in Busch Stadium in 1980.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

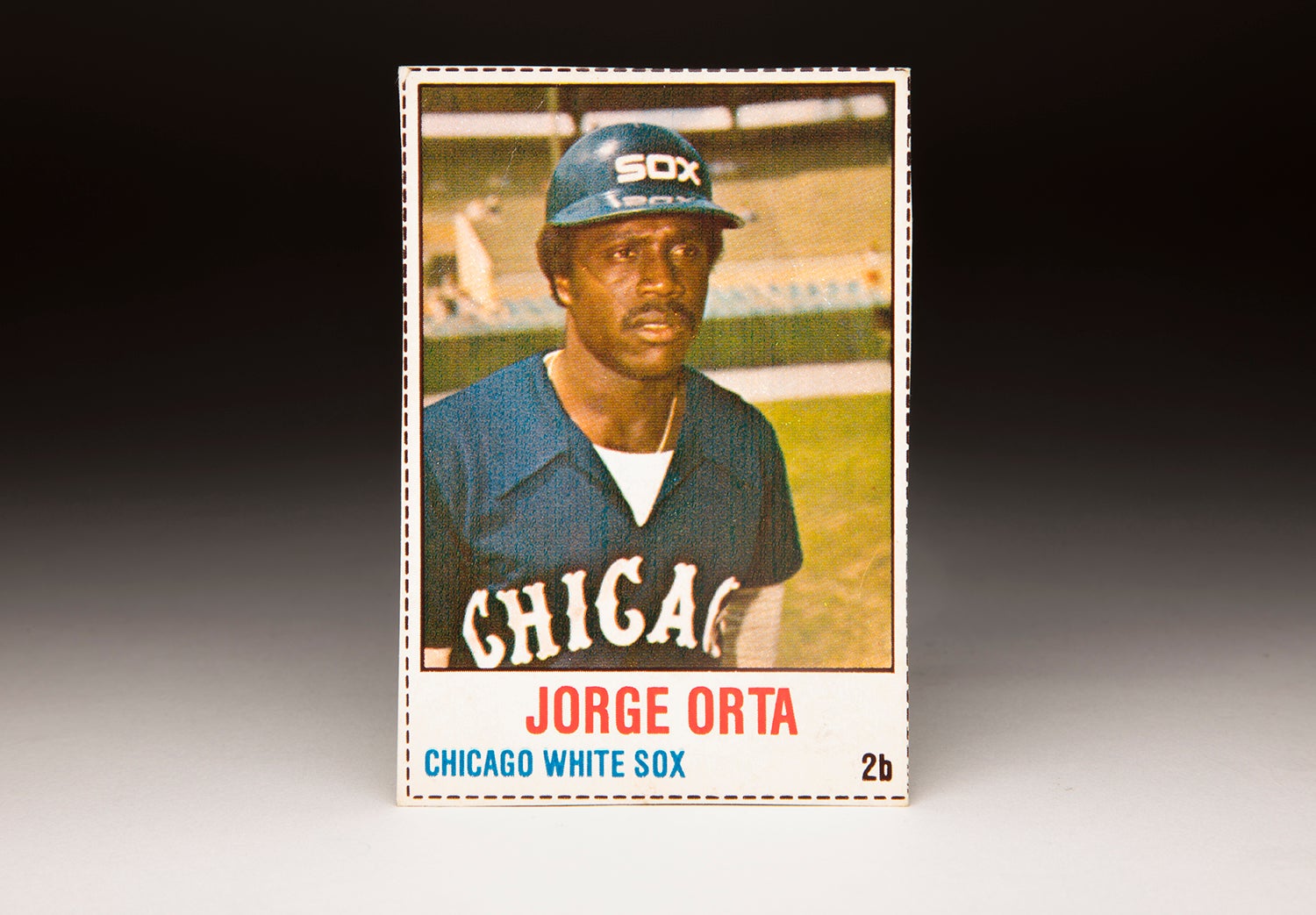

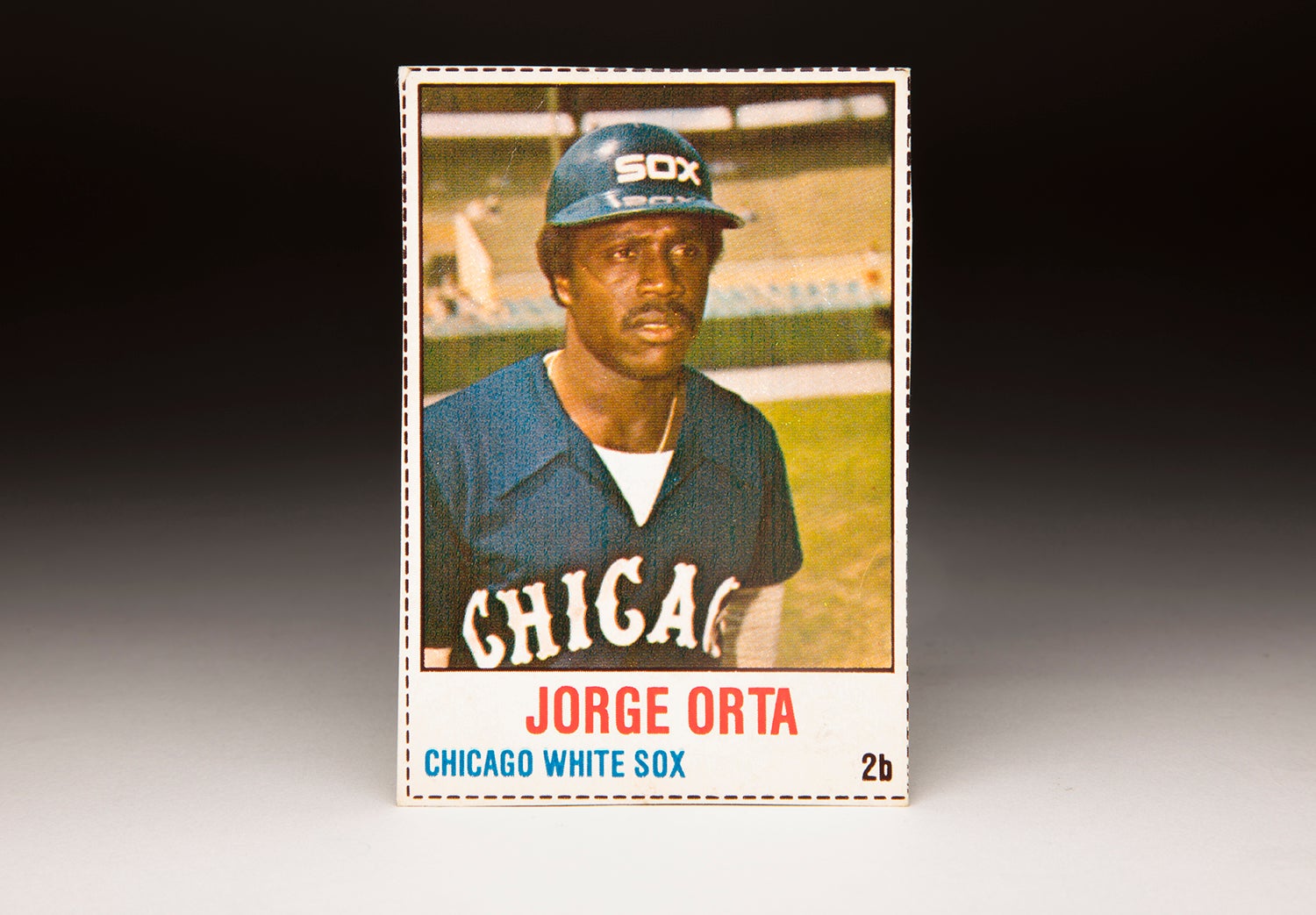

#CardCorner: 1978 Hostess Jorge Orta

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

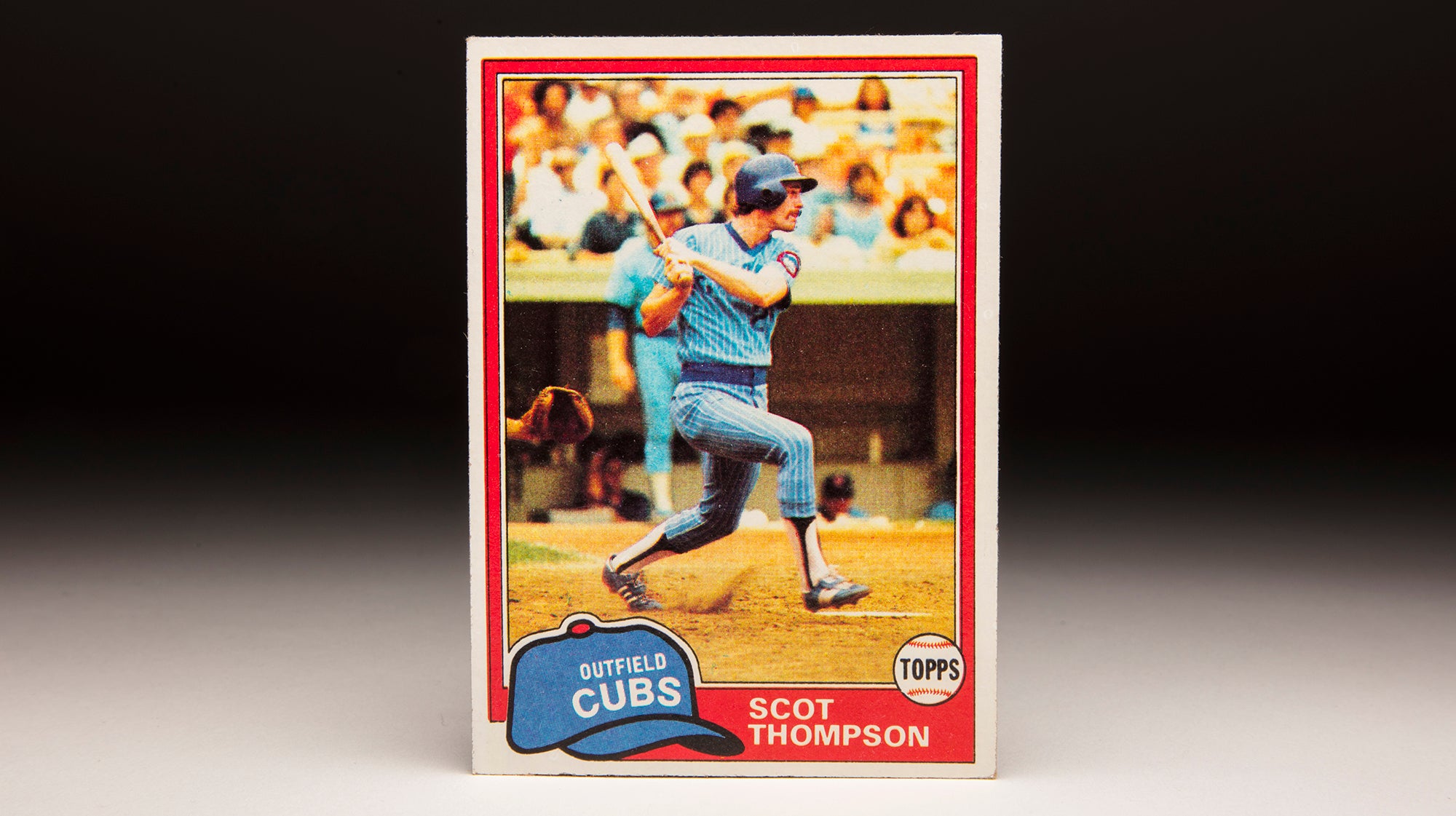

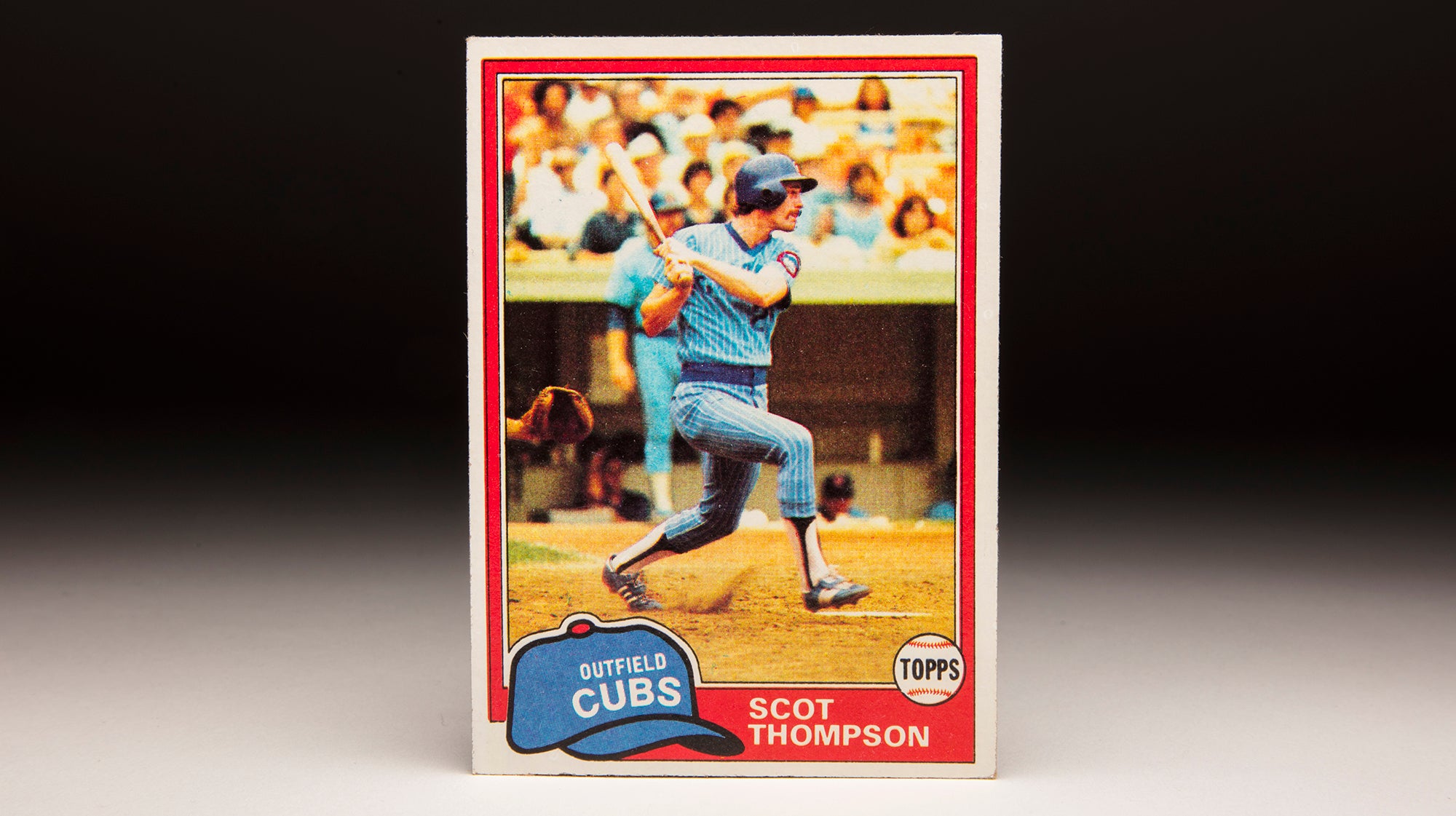

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Scot Thompson

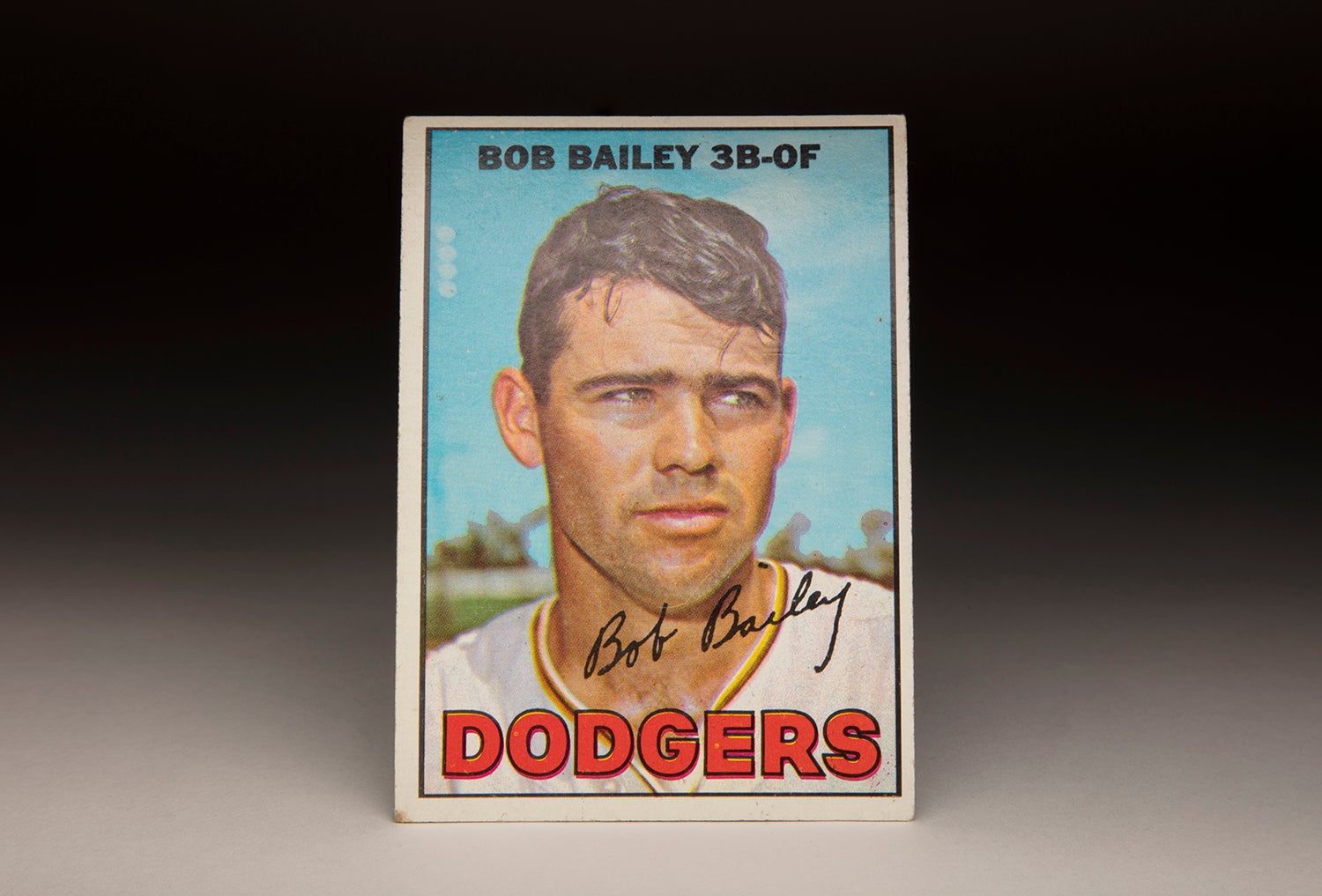

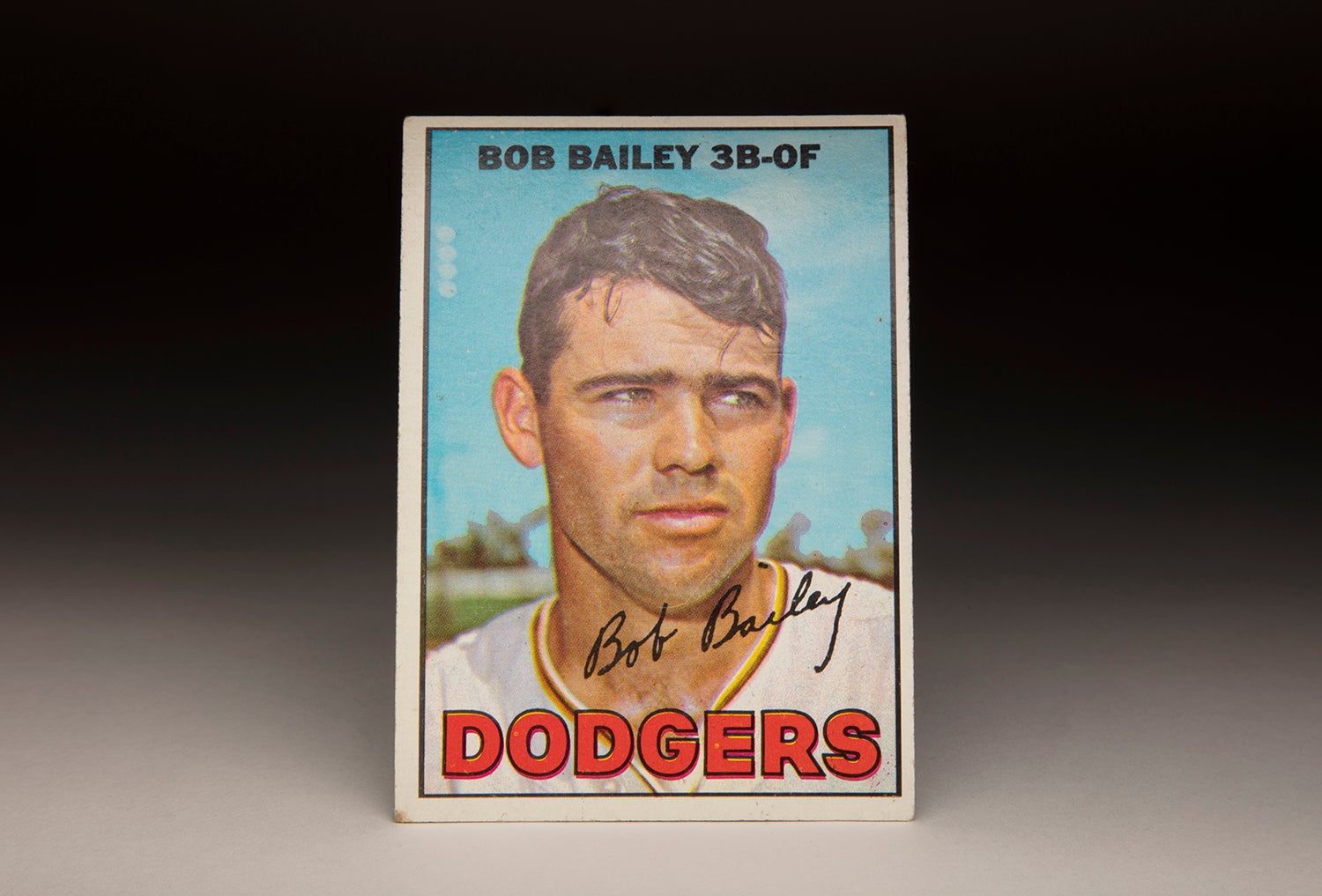

#CardCorner: 1967 Topps Bob Bailey

#CardCorner: 1978 Hostess Jorge Orta

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Scot Thompson