- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Andre Thornton

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Andre Thornton

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

In the mid-1970s, the Cleveland Indians briefly donned all-red uniforms that drew their share of criticism. Indians first baseman Boog Powell, who weighed in the vicinity of 250 pounds, once proclaimed that the uniforms made him look like a “massive blood clot.”

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

According to Todd Radom, author of the book, Winning Ugly, 37 players decided to “petition team ownership, demanding relief in the form of alternate navy blue jerseys.” The red uniforms were certainly colorful – perhaps a little too colorful, even in an era when bright colors were taking over double knits in both leagues.

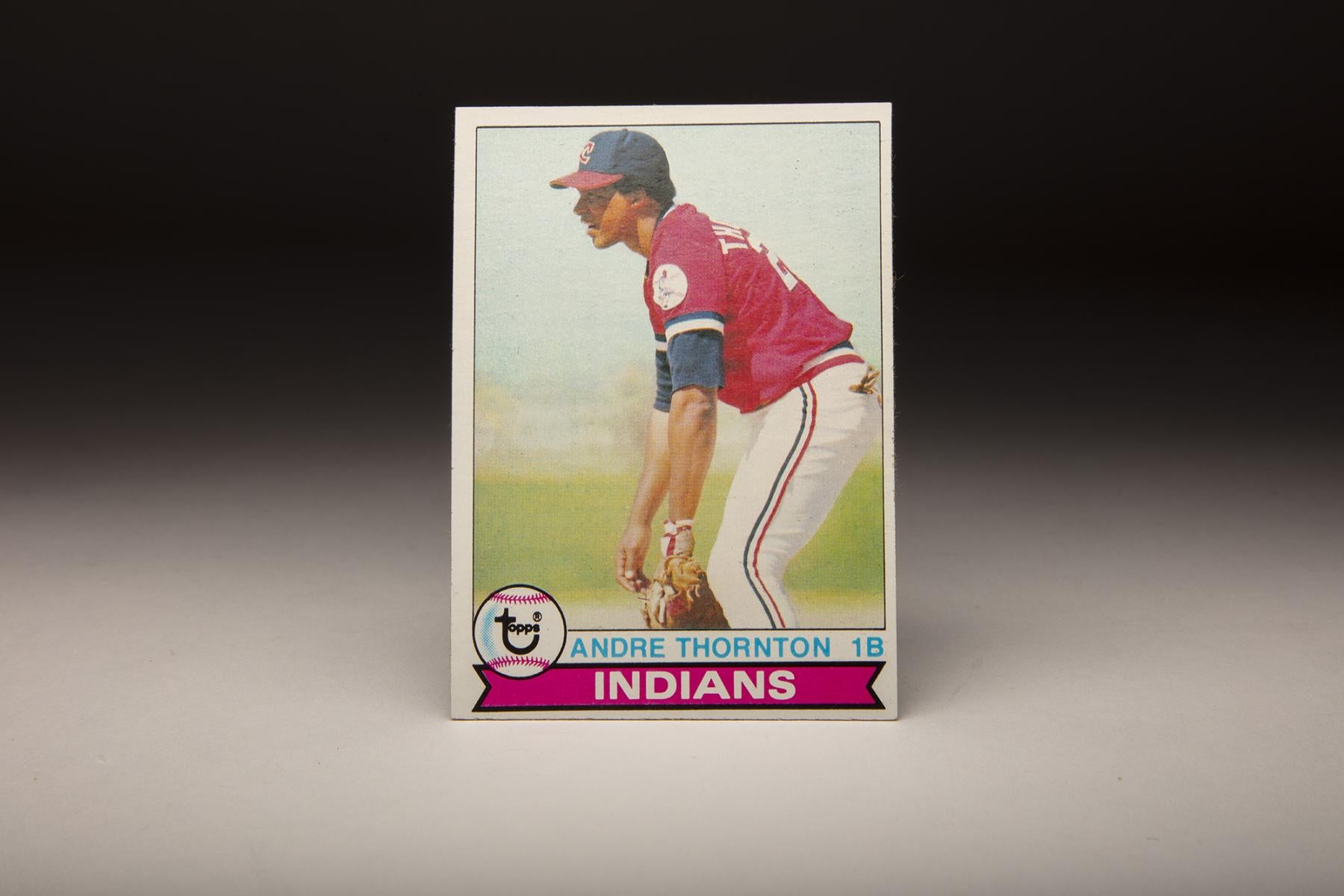

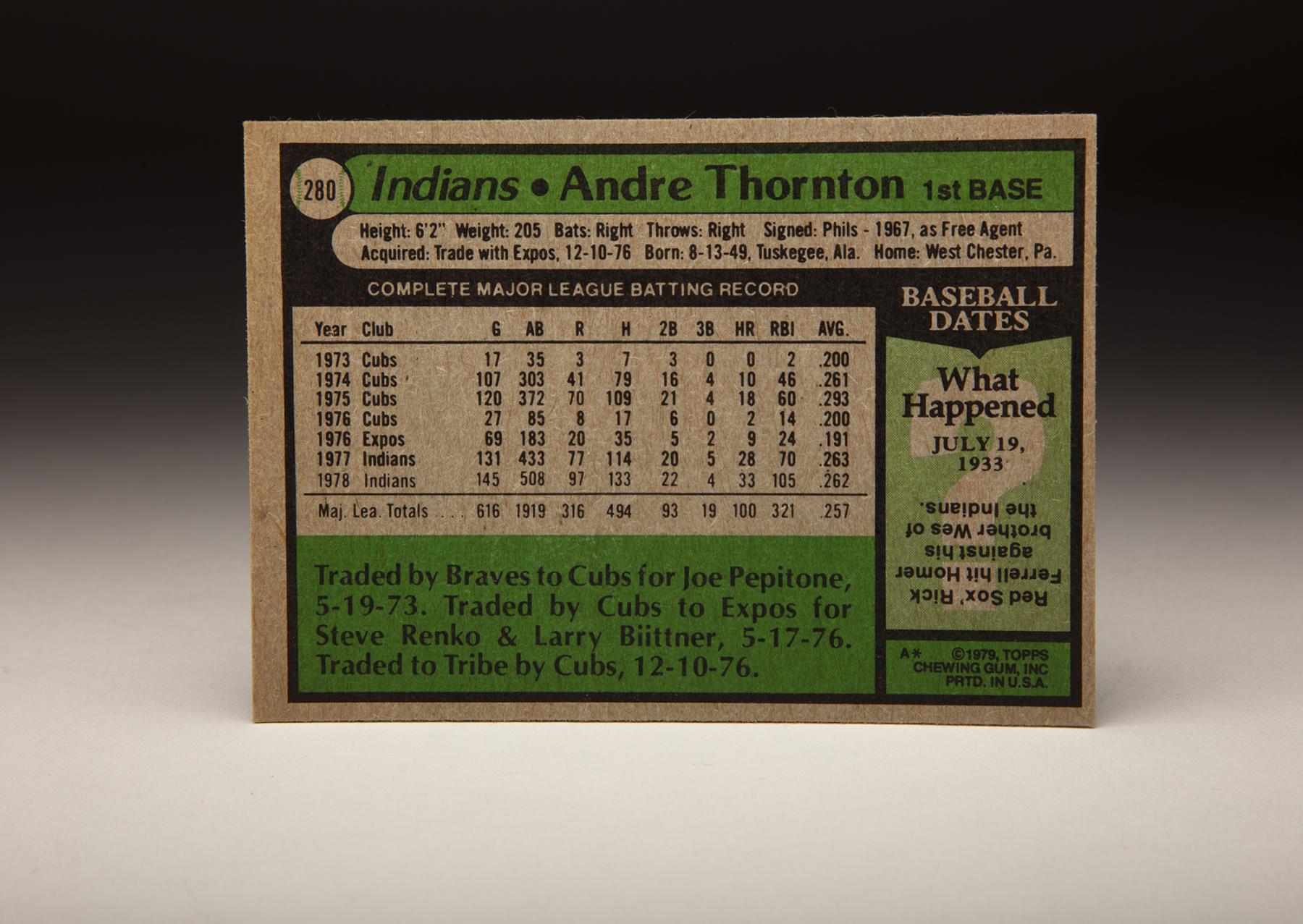

Later on, the Indians gradually moved away from the all-red appearance, as they started to wear a combination of white pants with a solid red jersey. It wasn’t as gaudy as the all-red look, but retained a nice touch of color, which was counterbalanced by the traditional white pants. In the 1979 Topps set, several Indians wore this uniform combination on their cards, including shortstop Tom Veryzer and right-handed pitcher Wayne Garland.

Perhaps none of the Indians looked any better than slugging first baseman Andre Thornton did on his 1979 card. On what appears to be a sun-splashed day during Spring Training, the photographer has given us a good look at Thornton as he moves into his crouch, anticipating the next pitch of the exhibition game. The photo also shows the large white logo the Indians sported on their left sleeve, along with the two-toned cap the team wore at that time. I must say that I like this uniform.

It’s also easy to like the player, given what Thornton has gone through in his life and how he has responded to the difficulties he has faced.

Thornton’s baseball story traces back to his days in Phoenixville, Pa., where he not only starred in baseball, but played football and basketball. He also excelled in billiards, to the point where he spent hours at a local pool hall playing for money.

Eligible to be drafted in 1967, Thornton was bypassed by all 20 major league teams. But the Philadelphia Phillies invited Thornton to a 1967 tryout at their aging ballpark, Connie Mack Stadium. Thornton showed good power that day, hitting several home runs against Phillies coach Larry Shepard.

About a week later, Phillies scout John Ogden traveled to Phoenixville, tracked Thornton down at the Golden Cue Pool Hall and signed him to his first contract.

The Phillies assigned Thornton to the Northern League and their affiliate in Huron, S.D. Other than a couple of his minor league teammates, Thornton could not find any black residents of Huron. That represented a bit of culture shock to Thornton, who had grown up in an integrated neighborhood in Pennsylvania.

A combination third baseman and outfielder, Thornton played in only 19 games for Huron – and struggled. He batted .182 with only one home run.

The following year, he decided to enlist in the National Guard, while remaining in the Phillies’ farm system. Assigned to Fort Dix, Thornton underwent an epiphany, as he delved into religion and became a Christian.

In the meantime, the Phillies moved Thornton on to the Northwest League, where he put up mediocre numbers in 1968 while switching from third base to first base. The following summer, the Phillies assigned him to Spartanburg of the Western Carolinas League, where he began to turn the corner. He showed power for the first time in his pro career, clubbing 13 home runs and slugging .452.

After a setback in 1970, Thornton blossomed in ’71. Playing at Double-A Reading, he hit 26 home runs and drew 76 walks. With that kind of production, Thornton earned a promotion to Triple-A to start the 1972 season.

Thornton was now a legitimate prospect, but he also faced a logjam in Philadelphia. The Phillies already featured veteran first baseman Deron Johnson, who had hit 33 home runs in 1971. Plus they had a top young prospect in Greg Luzinski, whom some considered the heir apparent to Johnson. And then there was Willie Montanez, who was currently manning center field but was far better suited to playing first base.

The Phillies had too many first basemen – and not enough pitching. So at the June 15 trading deadline, they sent Thornton to the Atlanta Braves for two pitchers, Jim Nash and Gary Neibauer. With the Braves, only one player was blocking him at first base, but that happened to be a fellow named Hank Aaron, who was 38, but showing no signs of slowing down.

Assigned to Triple-A Richmond, Thornton hit 14 home runs over the balance of the 1972 season. Returning to Richmond in ’73, he started off the new season in a slump. In the middle of May, the Braves decided to trade Thornton, sending him to the Chicago Cubs for veteran first baseman/outfielder Joe Pepitone.

In contrast to the Braves and Phillies, the Cubs had no preponderance of talent at first base, where an aging Jim Hickman was struggling to keep his job. In July, the Cubs recalled Thornton, giving him his first taste of the big leagues after nearly seven full seasons of minor league apprenticeship. Thornton played only sporadically for the Cubs that summer, but his days as a minor leaguer had come to an end.

The Cubs saw enough of Thornton to give him more regular playing time in 1974. He flashed some power, hitting 10 home runs in 107 games. Jim Marshall, who had replaced Whitey Lockman as Cubs manager in midseason, offered a full endorsement of Thornton.

“He’s come a long way in just this one season (1974) and has yet to reach his potential,” Marshall told Jerome Holtzman, corresponding for the Sporting News. “He’s going to be an even better hitter. But I don’t know how much better he can be in the field. He’s an outstanding fielder right now.”

In 1975, Marshall gave Thornton even more playing time and watched him produce big numbers: a .293 batting average, 18 home runs and a spectacular OPS of .944. With his powerful right-handed swing, Thornton looked like a perfect fit to play at Wrigley Field. In 1976, he started off the season slowly, leading the Cubs to make a rushed decision.

On May 17, the Cubs traded him to the Montreal Expos for right-handed pitcher Steve Renko and singles-hitting first baseman Larry Biittner. It was a trade meant to address Chicago’s need for starting pitching, but it was a move that the franchise would come to regret.

Thornton spent the rest of the Bicentennial year platooning with Mike Jorgensen at first base and making occasional appearances in right field. Unwilling to commit to Thornton as their everyday first baseman, the Expos traded him that winter, sending him to Cleveland for right-hander Jackie Brown.

At the age of 27, Thornton had received the kind of break that his stop-and-start career badly needed. The Indians had big plans for Thornton. With an aging Boog Powell at first base, the Indians projected Thornton as his successor. Surely enough, the Indians released Powell during the spring of ’77, clearing first base for Thornton. Given the chance to play every day, Thornton hit 28 home runs and slugged .527. He also played an excellent first base.

As well as Thornton played that summer, an unspeakable tragedy would hit him and his family that fall. On Oct. 17, Thornton, his wife Gertrude, and their two children, Andre, Jr. and Theresa were traveling in a van on the Pennsylvania Turnpike when a snowstorm with high winds hit the area.

The van veered off the road and flipped over in a ditch.

The accident took the lives of Thornton’s wife and daughter, leaving behind only him and his son, who was injured in the crash but would make a full recovery. It was a devastating tragedy, but it only made Thornton embrace his religious beliefs more forcefully. He also realized that he would have to concentrate his efforts in taking care of his son, who was still so young that he didn’t fully understand what had happened to the family.

Later that winter, Indians manager Jeff Torborg placed a call to Thornton, concerned about his slugger’s well-being.

“He was on our minds constantly, so I told my wife I was going to give Andy a call,” Torborg told the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “hoping maybe I could boost his morale a bit. We spoke on the phone for 30 minutes; I think I spoke a minute. Andy spoke the other 29 – and he strengthened me.”

It was a remarkable show of courage and fortitude on the part of Thornton, but not completely surprising to those who had come to know his character.

Somehow Thornton managed to play remarkably well in 1978. He hit 33 home runs (a career high), walked 93 times, and slugged .516, numbers that allowed him to earn some support in the American League MVP balloting.

His numbers would dip slightly in 1979, as his batting average fell to .233, but his power production remained substantial. After the season, he received the Roberto Clemente Award for his inspiring efforts off the field.

Even more importantly, Thornton remarried in 1979, wedding gospel singer Gail Jones. The marriage would produce two children.

With his personal life and career having been revitalized, Thornton would face additional setbacks over the next two seasons. More specifically, injuries curtailed Thornton. In the spring of 1980, he suffered a knee injury that required surgery and sidelined him for the entire season. In 1981, a pitched ball in a Spring Training game broke his hand, delaying his comeback from the knee surgery. The latest injury, along with a lengthy players strike in the middle of the season, limited him to 69 games.

In 1982, with his career seemingly on the wane, Thornton faced a critical juncture. Now rendered a DH because of the acquisition of Mike Hargrove, Thornton bounced back beautifully, hitting 32 home runs while reaching career highs in RBIs (116) and walks (108). The Sporting News named him Comeback Player of the Year. He would remain productive over each of the next two seasons, becoming a bright spot for an Indians team that perennially found itself out of contention.

It was not until 1985 and ’86 that Thornton began to show significant decline, his batting averages falling to .236 and .222 in those two seasons. Limited to 36 games in 1987, the 37-year-old called it quits that winter.

Since his baseball days, Thornton has found success in business. He has owned several Applebee’s Restaurants and currently serves as the CEO of ASW Global, a company that specializes in warehousing. He also continues to make frequent public speaking appearances at churches and charitable organizations around the country.

While many ballplayers have encountered difficulties in making the transition to life without baseball, Thornton represents a refreshing success story. It’s especially gratifying to see good fortune come the way of a man whose early baseball career met with repeated frustration and who was then devastated by a horrific accident that took half of his family away.

Again and again, Andre Thornton has found a way to come back. Yes, good guys can finish first, too.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

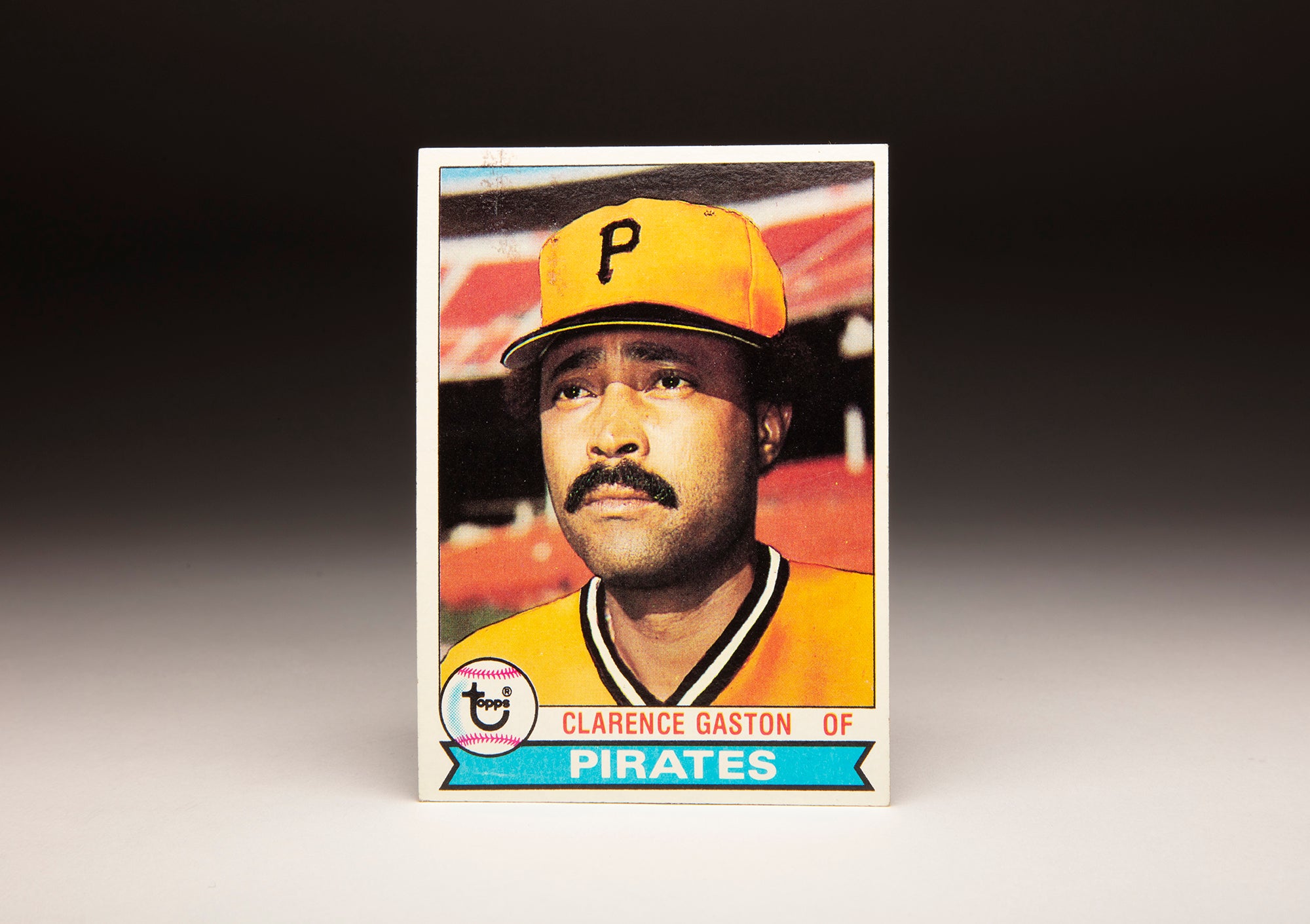

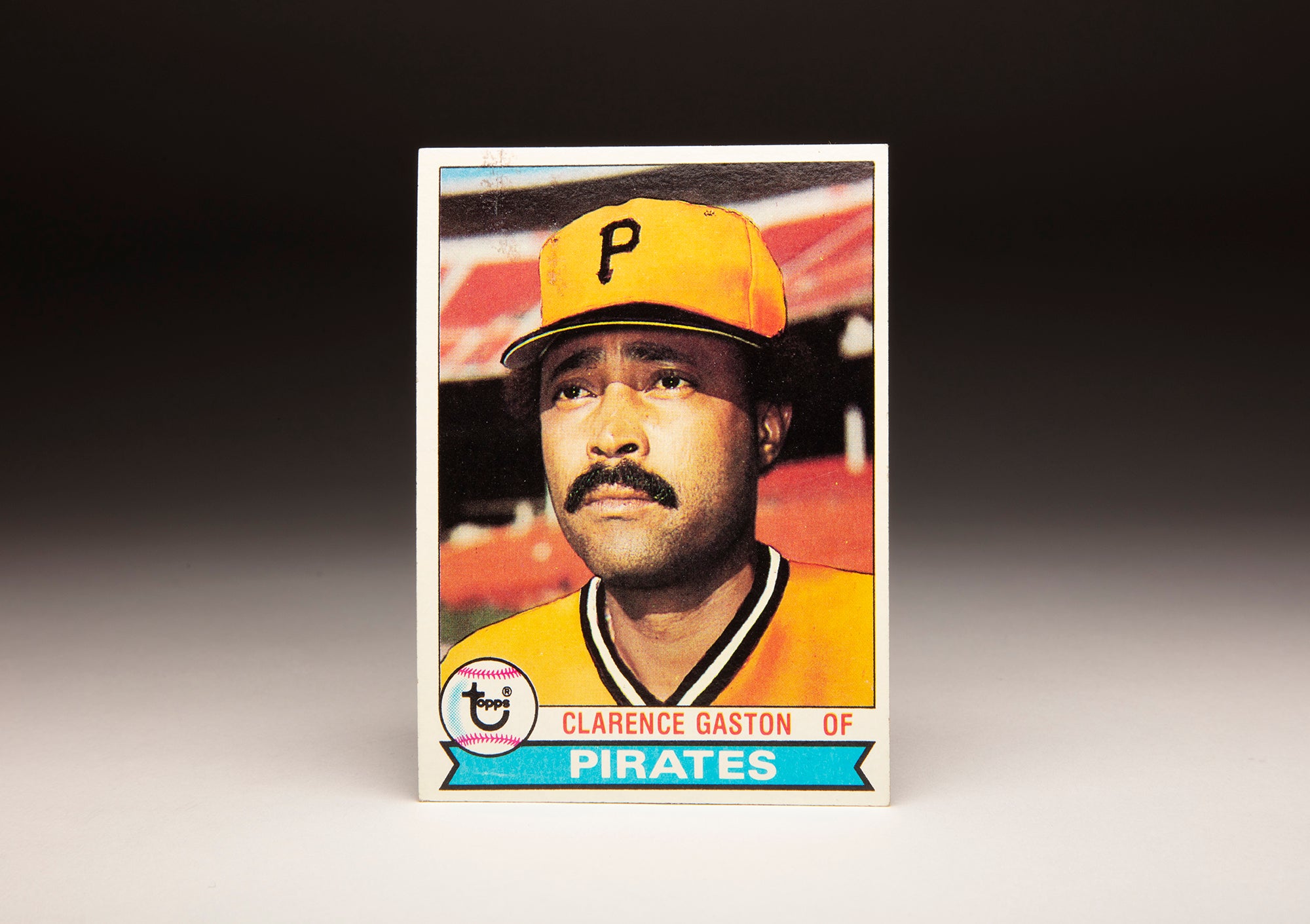

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Clarence Gaston

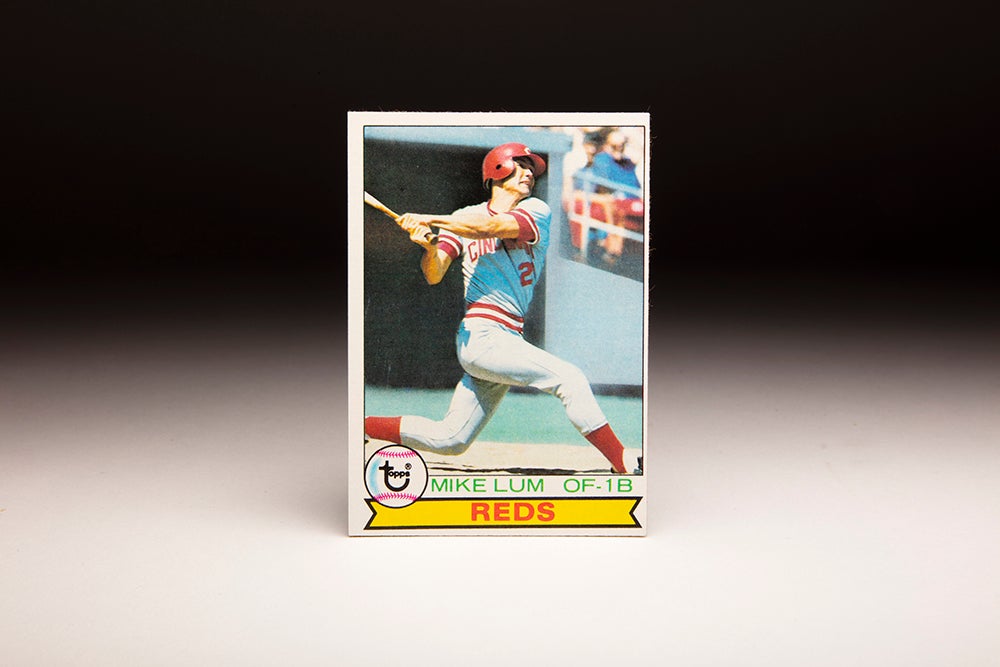

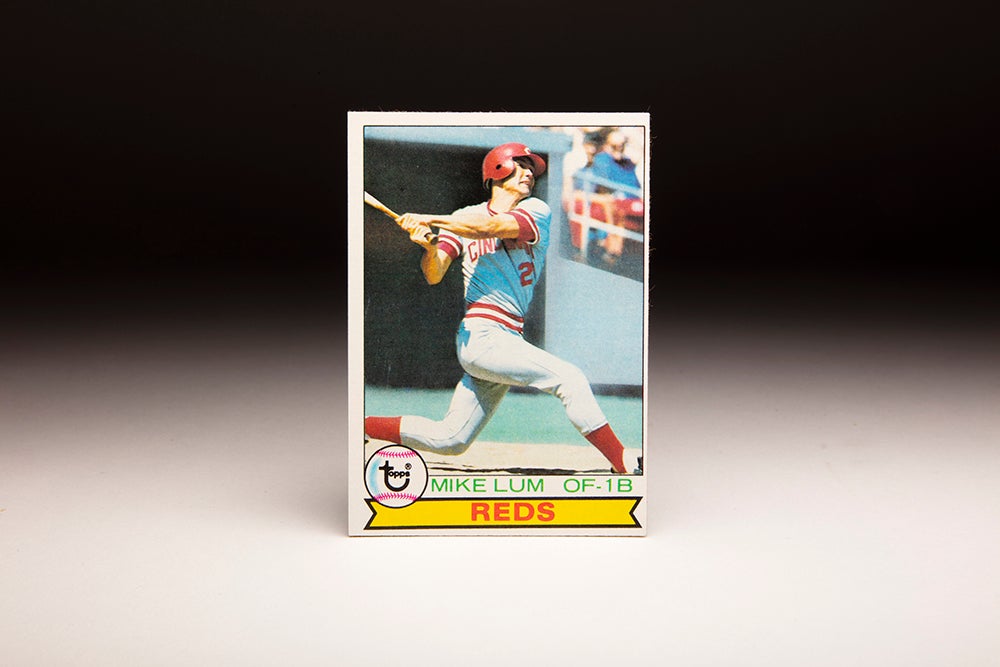

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Lum

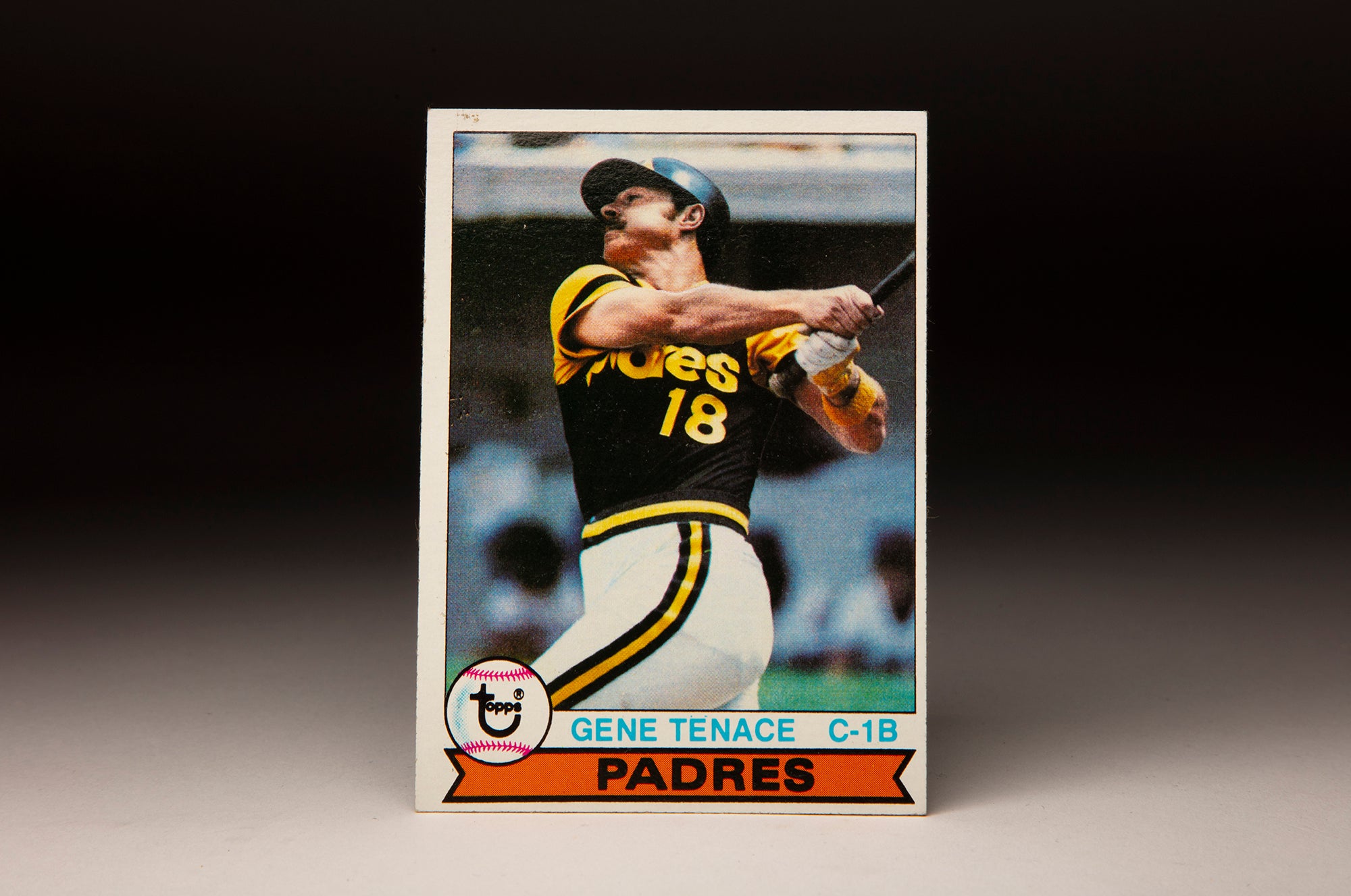

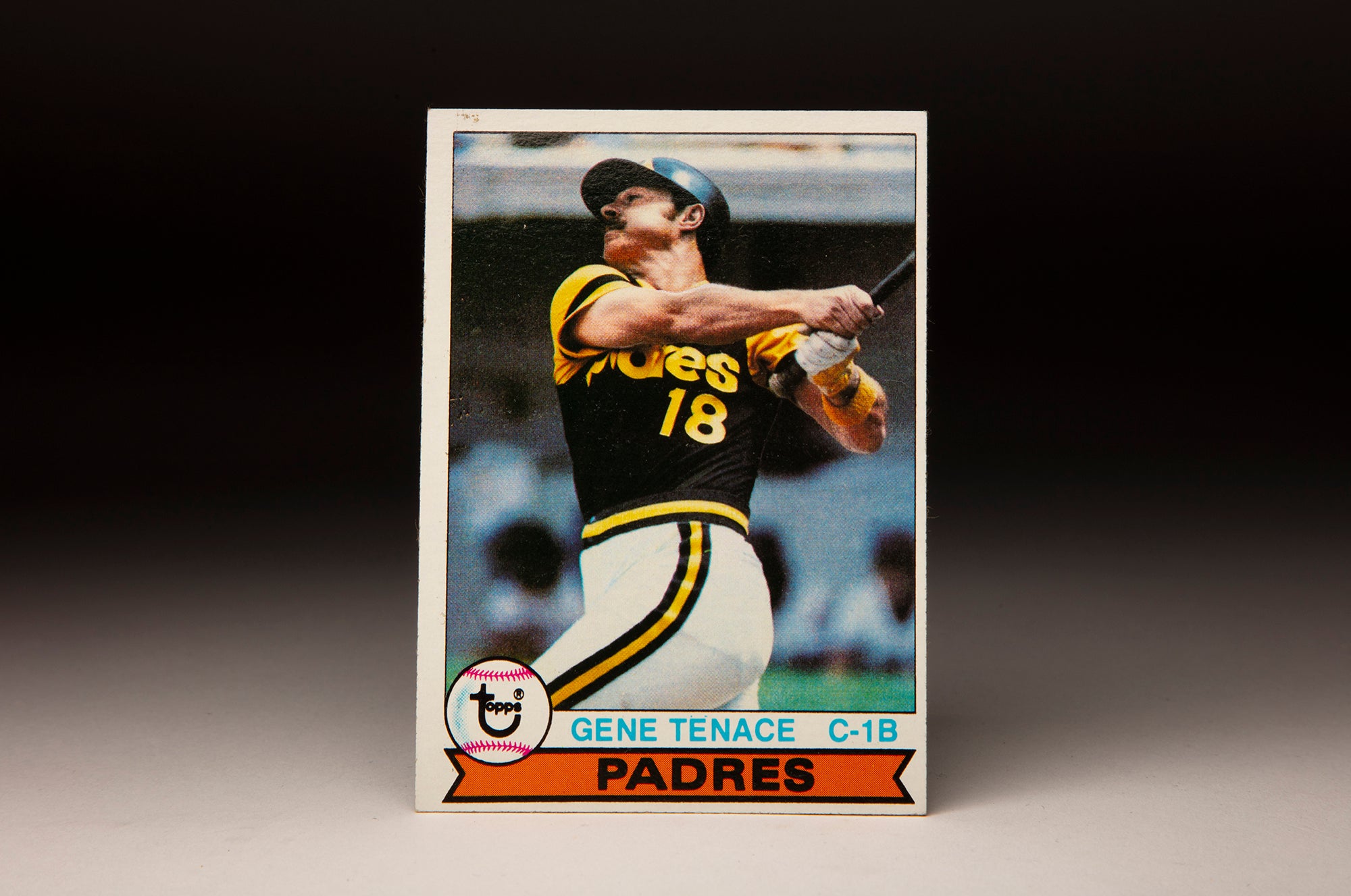

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Gene Tenace

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bud Harrelson

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Clarence Gaston

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Lum