- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Lum

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Mike Lum

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

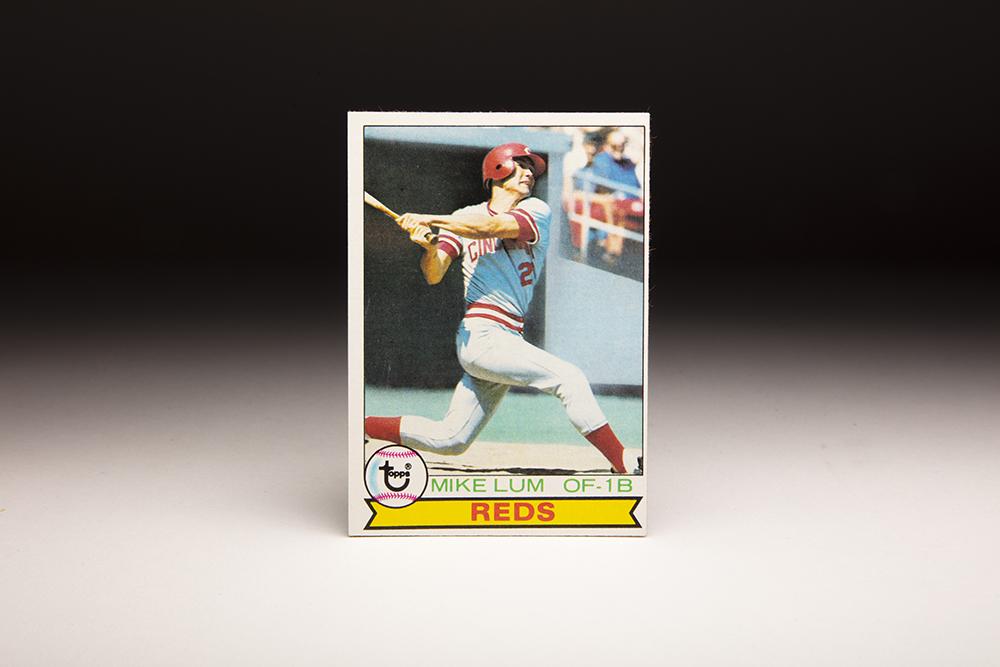

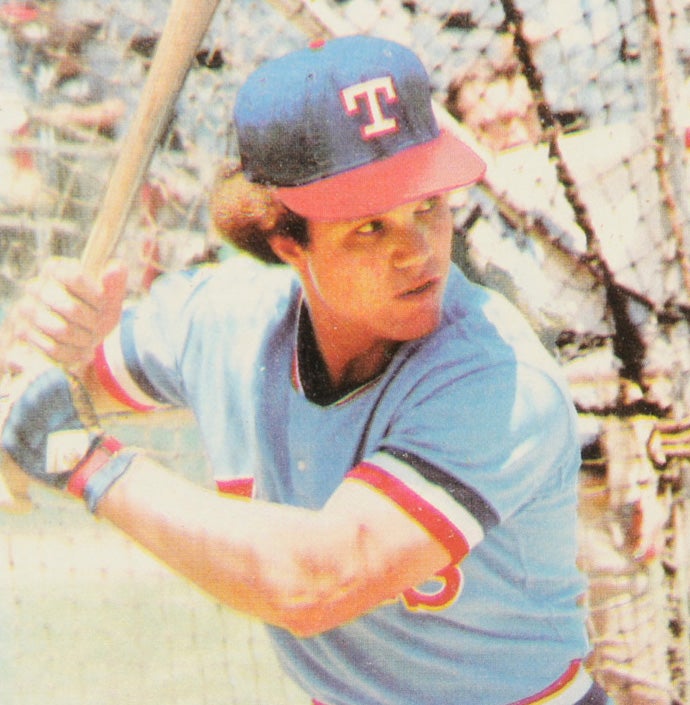

Can a baseball card capture the perfect swing? Probably not, since a card’s photograph is static and doesn’t show us the motion of the bat and the movement of the hands and the body.

But a card might be able to capture the perfect follow-through to a swing. And if that’s the case, I don’t know if I’ve ever seen a more picturesque follow-through on a baseball card than the one belonging to Mike Lum on his 1979 Topps card.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Everything is just the way it should be on Lum’s card. His right leg is striding forward, while his left leg is planted, with just the right amount of spacing between the two limbs. Lum looks perfectly balanced here. With regard to his upper body, his bicep muscles are properly flexed, while his bat is in a good finishing position. And just to complete the picture, Lum’s facial expression is that of a grimace, a reflection of the hard work that goes into hitting a baseball.

As good as the follow-though looks, I have no idea where the ball ended up. Lum’s head is tilted slightly upward, indicating that perhaps he has hit a fly ball. Based on a review of his 1978 season, when the photograph was taken, I don’t think that he has hit a home run here. In ‘78, Lum hit three home runs on the road – one at Shea Stadium and two in Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium – but neither of those road ballparks is pictured here.

Perhaps the ball ended up as a deep fly, caught by the right fielder or center fielder. Or maybe it ended up as a long double. Whatever the end result, it shouldn’t detract from that wonderful follow-through.

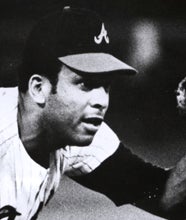

Lum’s 1979 Topps card is one of four that shows him wearing the colors of the Cincinnati Reds. He is best remembered, however, for playing with the Atlanta Braves, the franchise that originally drafted him out of Roosevelt High School in Hawaii. That was in 1963, when the Braves were still located in Milwaukee. By the time that Lum made the major leagues in 1967, the Braves had moved to Atlanta.

Lum (pronounced LUHM and not LOOM) came from a non-traditional baseball background. Born in Honolulu to an American soldier and a Japanese woman, Lum did not come to know his parents because the unmarried couple put him up for adoption. A Chinese couple succeeded in adopting and raising him, leading to many stories that claimed Lum came from Chinese heritage. In reality, he was the first American of Japanese heritage to play in the major leagues – and only the fourth Hawaiian to make it to the big leagues.

Lum endured a mediocre professional debut in the Georgia-Florida League in 1963. There he had to learn a new position; the Braves moved him from first base, his high school position, to the outfield. Playing for Waycross, a small town in Georgia, Lum also experienced culture shock. In Hawaii, he had seen little in terms of outward racism. But in the American South, he noticed the segregated water fountains, along with separate hotels for his black teammates. It was like nothing Lum had ever before seen.

In 1964, Lum moved up to Binghamton of the Single-A NY-Penn League, where he excelled with a .307 batting average and 18 home runs. After another good season at Yakima of the Northwest League, Lum moved up to Double-A in 1966 and Triple-A in 1967. He didn’t post overwhelming numbers at either of the latter stops, but the Braves saw enough to bring him to Atlanta in September of ’67.

The Braves gave him a looksee in center field; he didn’t hit much, but he was in the major leagues to stay.

In 1968, Lum received plenty of playing time as a fourth outfielder behind the veteran trio of Tito Francona, Felipe Alou and Hank Aaron. Lum showed versatility by handling all three outfield slots with finesse, but at the plate he struggled, batting only .224 with three home runs.

Lum filled the No. 4 outfield role again in 1969 and showed some improvement, as he lifted his batting average to .268. At one point, manager Luman Harris called Lum the best reserve outfielder in either league.

“I can’t think of a better extra outfielder on any club,” Harris told Wayne Minshew, corresponding for the Sporting News. “Also, he is as good a man on a team as I’ve seen. He has a great temperament for the game and plenty of desire.”

Outside of Harris’ glowing words, the most notable event of the season occurred when Harris called on him to pinch-hit for Aaron in the midst of a blowout game. (At the time, it was reported that Lum was the first player ever to pinch-hit for Aaron, but that’s not true. He was actually the third, after Johnny Blanchard and Lee Maye.) Stepping to the plate for the great Aaron, Lum socked a double, scoring two more runs for the Braves during an inning that saw the team bat around.

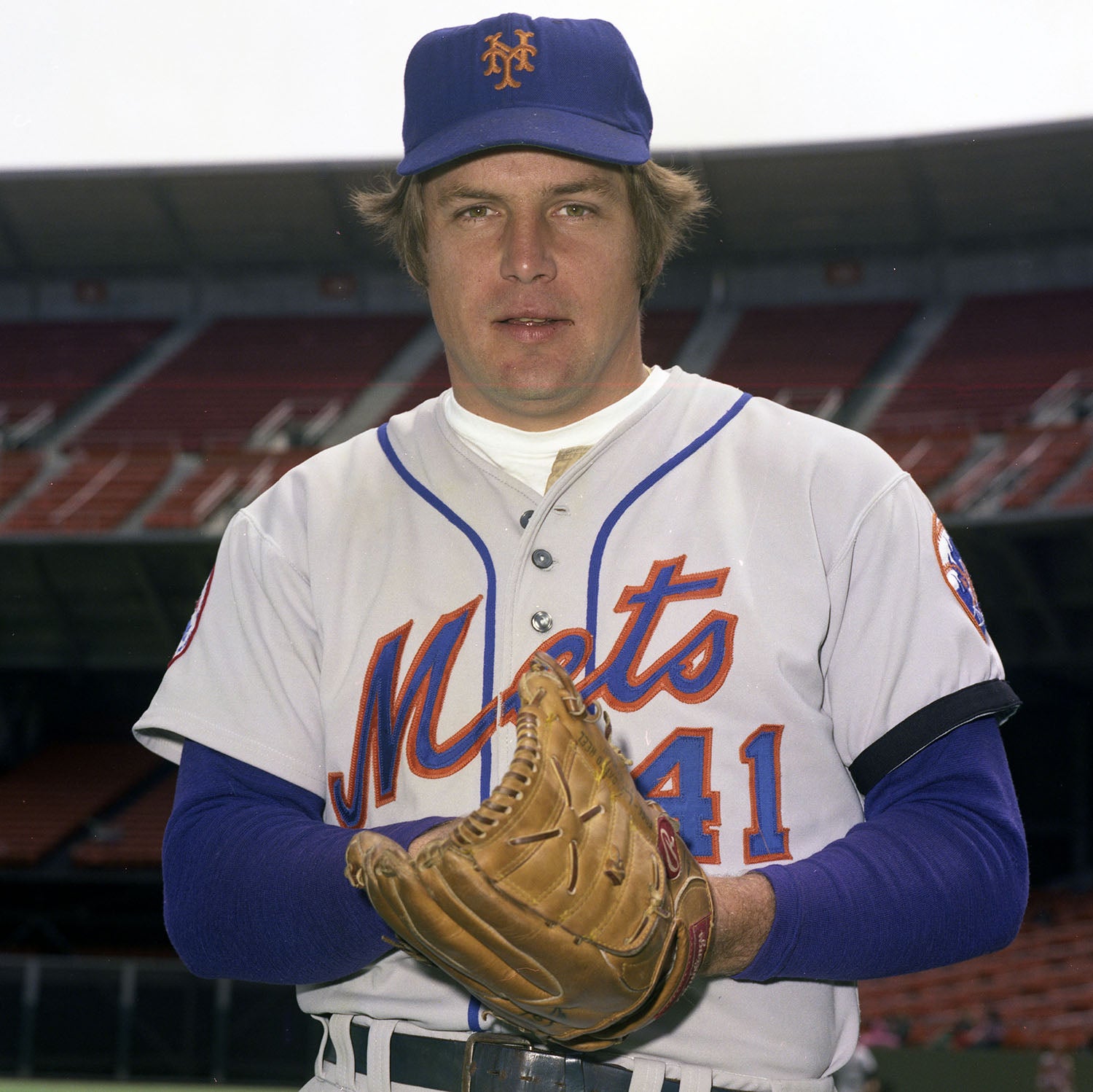

As a team, the Braves found success, winning the first ever Western Division title in the newly aligned National League. The Braves advanced to the NLCS against the New York Mets. Lum went 2-for-2 in the three-game series, but the powerhouse Braves’ lineup was held down by a Mets pitching staff led by Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman.

After another season of utility work in 1970, a season that was highlighted by a three home run-game against San Diego, Lum took on a greater role in 1971.

With veteran first baseman Orlando Cepeda limited to 73 games by sore knees, the Braves moved an aging Aaron to first base, creating space for Lum to play regularly in right field. The 25-year-old responded well to the challenge, playing a solid right field and hitting a respectable .269 with a .340 on-base percentage and 13 home runs.

The Braves hoped that Lum could build on that season in 1972, but the players’ strike wiped out the start of the season. During the strike, Lum received a jolt when he heard a local TV report that he and Dusty Baker had been traded to the Oakland A’s in a deal for Jim “Catfish” Hunter. The report came from a prankster (identifying himself as a member of the Braves’ front office), who placed a call to the local newsroom. Lum learned of the “trade” from Braves pitcher Ron Schueler. Shook up by the news, Lum frantically called up Braves traveling secretary Don Davidson and asked him if the story was true. After hesitating at first, Davidson assured him that no trade had been made.

Though he started the season in right field, Lum slumped so badly in 1972 that the Braves reduced his playing time against left-handed pitching. By season’s end, Lum’s batting average had sunk to .228. He finished with only nine home runs and a slugging percentage of just .350.

Then came a bounceback season in 1973. During the spring, Lum won the first base job over two rookies, Andre Thornton and Jack Pierce. Lum rewarded the Braves’ decision by reaching career highs in batting average (.294), home runs (16), and OPS (.813.) The season left Lum most satisfied.

“I came up [in 1967] and everybody called me Henry’s caddy,” Lum recalled in an interview with sportswriter Bob Spear. “And I never got a chance until [this season]. You better believe I got a lot of satisfaction out of the job I did in 1973.”

With most of the Braves’ attention shifting to Hank Aaron’s home run chase in 1974, Lum arrived at Spring Training with little fanfare. He lost playing time because of a broken bone in his thumb and a fracture of his cheekbone.

Replaced by Dave Johnson at first base, Lum appeared in only 104 games. He hit with good power but saw his batting average fall into the .230 range.

Another off season in 1975 convinced the Braves to move on from Lum. At the December Winter Meetings, the Braves worked out a one-for-one swap with the Reds, trading Lum for utility infielder Darrel Chaney.

The trade to the powerhouse Reds eliminated any chance of Lum again becoming an everyday player. The Reds already featured a terrific starting outfield of George Foster, Cesar Geronimo and Ken Griffey, Sr., with young Ed Armbrister and veteran Bob Bailey providing backup. Lum joined Armbrister and Bailey as reserves who pinch-hit and gave rest to the regulars as needed.

The Reds, however, did provide Lum with the chance to play for a winning team. Boasting a dynamic offense, range on defense, and a deep bullpen, the Reds ran away with the National League West and then steamrolled Philadelphia and New York in the playoffs and World Series, respectively. In one of the most convincing performances by a world championship team in history, the “Big Red Machine” won its second consecutive title – and the first for Lum. Although he received only one at-bat in the NLCS and no playing time in the World Series, he still earned a World Series ring as a member of The Big Red Machine.

Lum continued to play a utility role for the Reds in ’77 and ’78, filling in at all three outfield positions and backing up Dan Driessen at first base. The Reds called on him to pinch-hit frequently, a role that Lum at which he became more and more accomplished. The two seasons came without a reward at the end, however, as the Reds finished second in back-to-back pennant races.

After the 1978 season, the Reds traded Lum back to Atlanta, allowing him to move into the “Braves Phase 2” part of his career. Lum played well in 1979 before slumping the following two seasons. In the middle of the strike-interrupted 1981 season, the Braves released Lum, who handled the move with grace. He soon found work with the Chicago Cubs, where he finished out his big league tenure as a backup first baseman and corner outfielder. Lum closed out his career with 103 pinch-hits, putting him sixth on the all-time list at the time.

Lum wasn’t done with baseball just yet. In a move that made particular sense given his Asian heritage, Lum found work in the Japanese Leagues. He signed a contract with the Yokohama Taiyo Whales, where he performed respectably in 1982. Lum enjoyed playing in Japan, but was disappointed when the Taiyo Whales chose not to invite him back for a second season.

Although Lum’s playing days had come to an end, his association with baseball would continue. Hank Aaron, who was heading up the Braves’ farm system, placed a call to Lum and offered him a job as a Spring Training instructor. Lum then put in some time for the Braves’ affiliate in the South Atlantic League before moving on to the Chicago White Sox system.

In 1986 and ’87, Lum worked for San Francisco and Kansas City, respectively, before becoming the Royals’ major league hitting instructor in 1988 and ’89. From there, he returned to the White Sox as their minor league hitting coordinator, a job he would hold for the next 15 years.

After the Sox won the World Series in 2005, they strangely fired Lum, telling him that he had “lost his passion” for the job. Lum didn’t agree; he found work with the Milwaukee Brewers, where he received a coaching award, and then the Pittsburgh Pirates. Even at age 72, Lum remains active with the Pirates, serving the organization as a senior advisor.

When Lum played, he was perhaps best known for being only the third player to ever pinch-hit for Hank Aaron. Years later, his legacy has changed; he’s now known as one of the game’s great teachers, especially when it comes to the art of hitting. For the man who had one of the finest follow-throughs ever seen on a baseball card, that seems just about right.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bud Harrelson

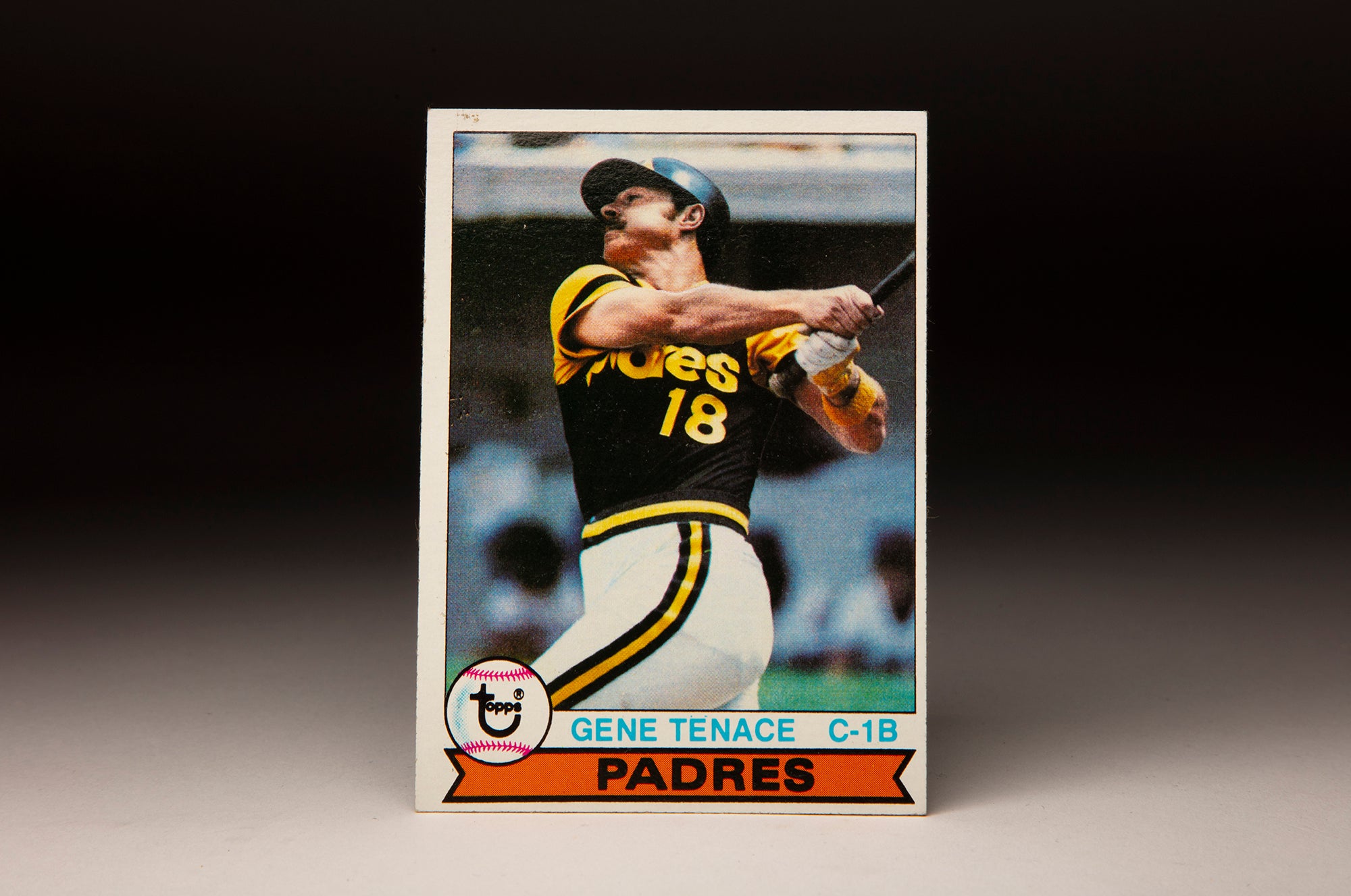

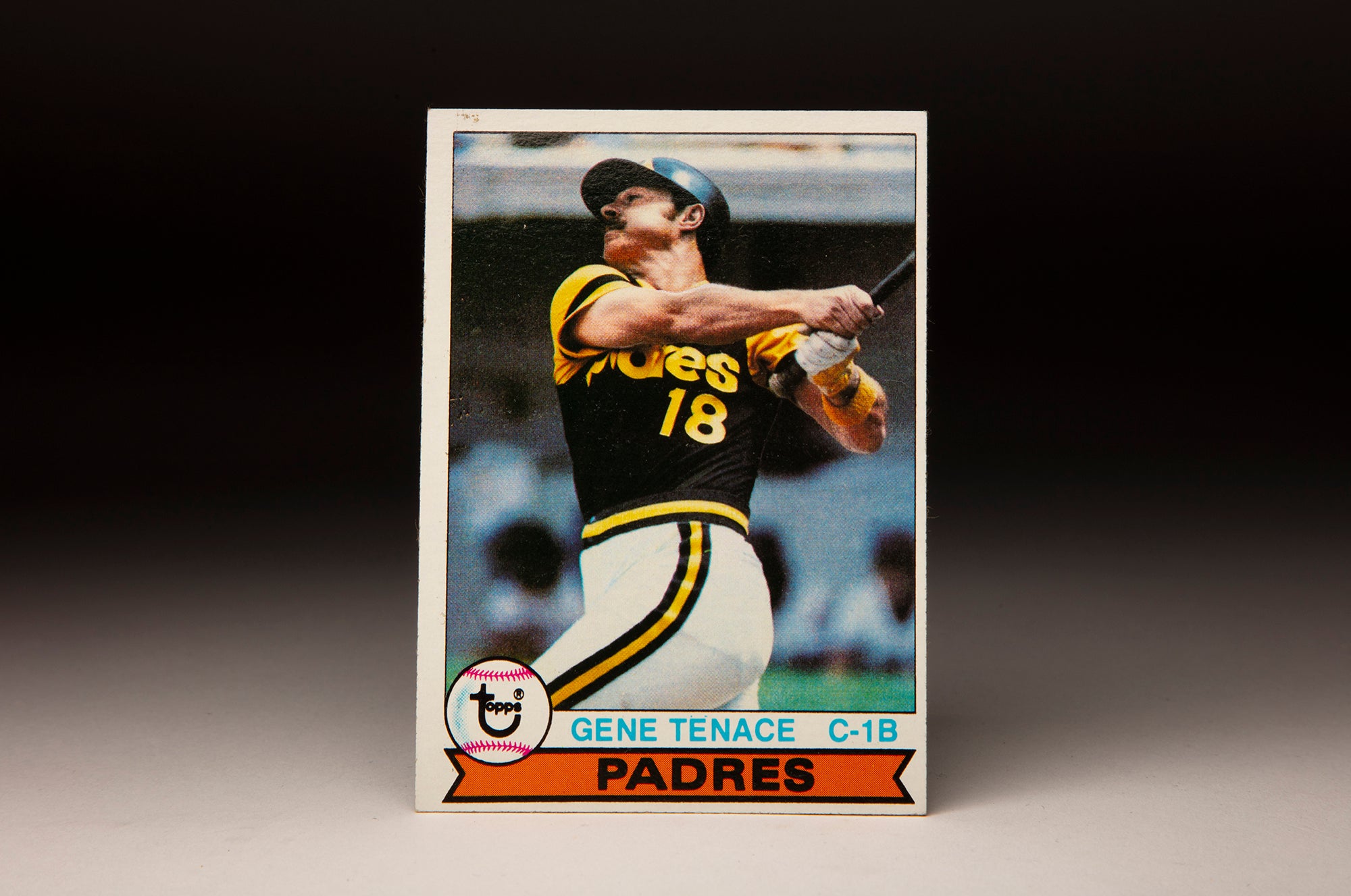

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Gene Tenace

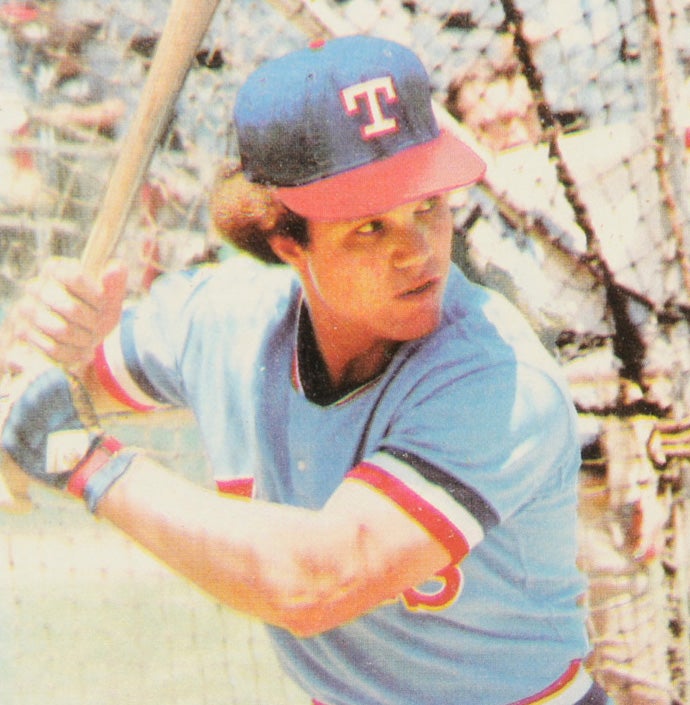

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

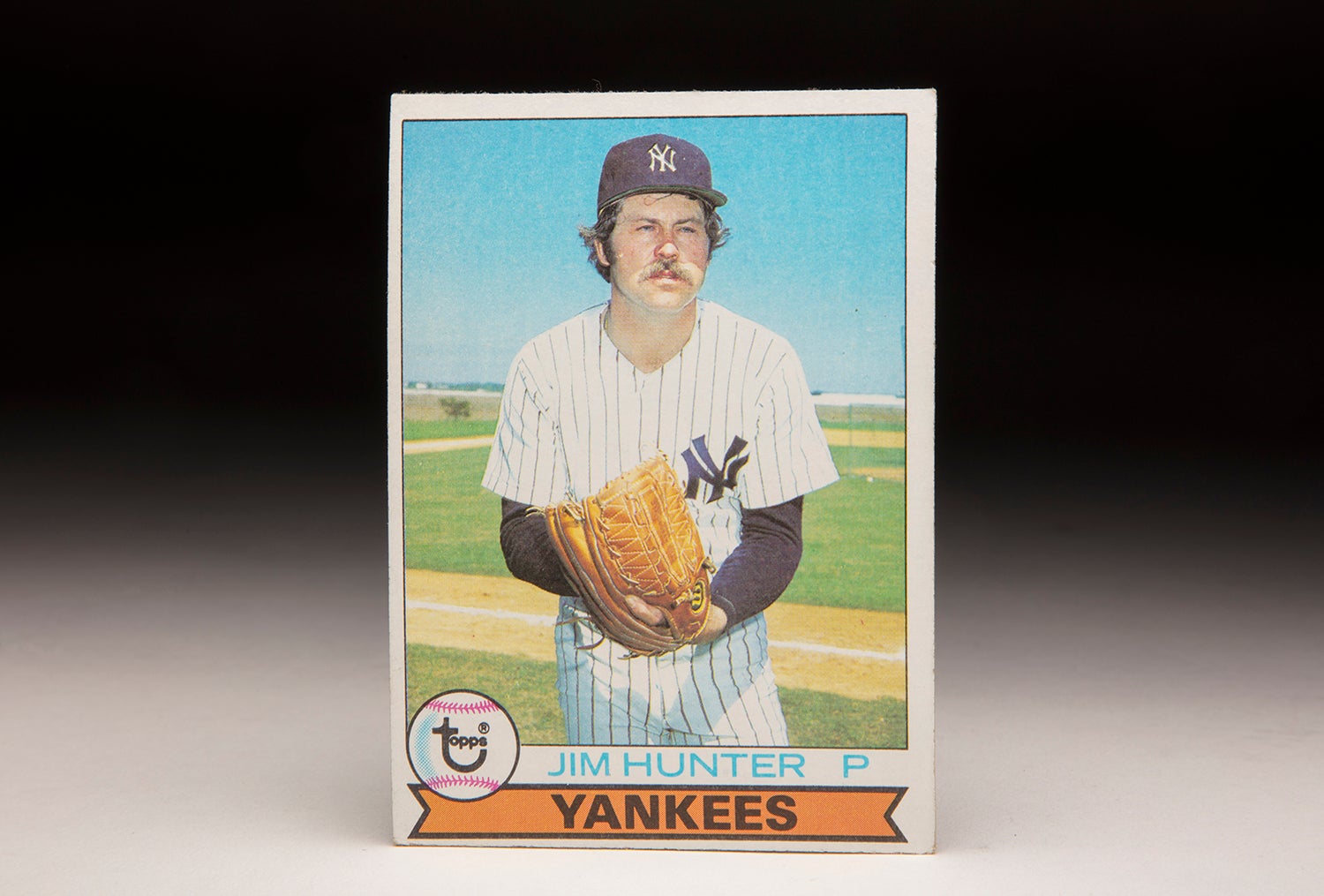

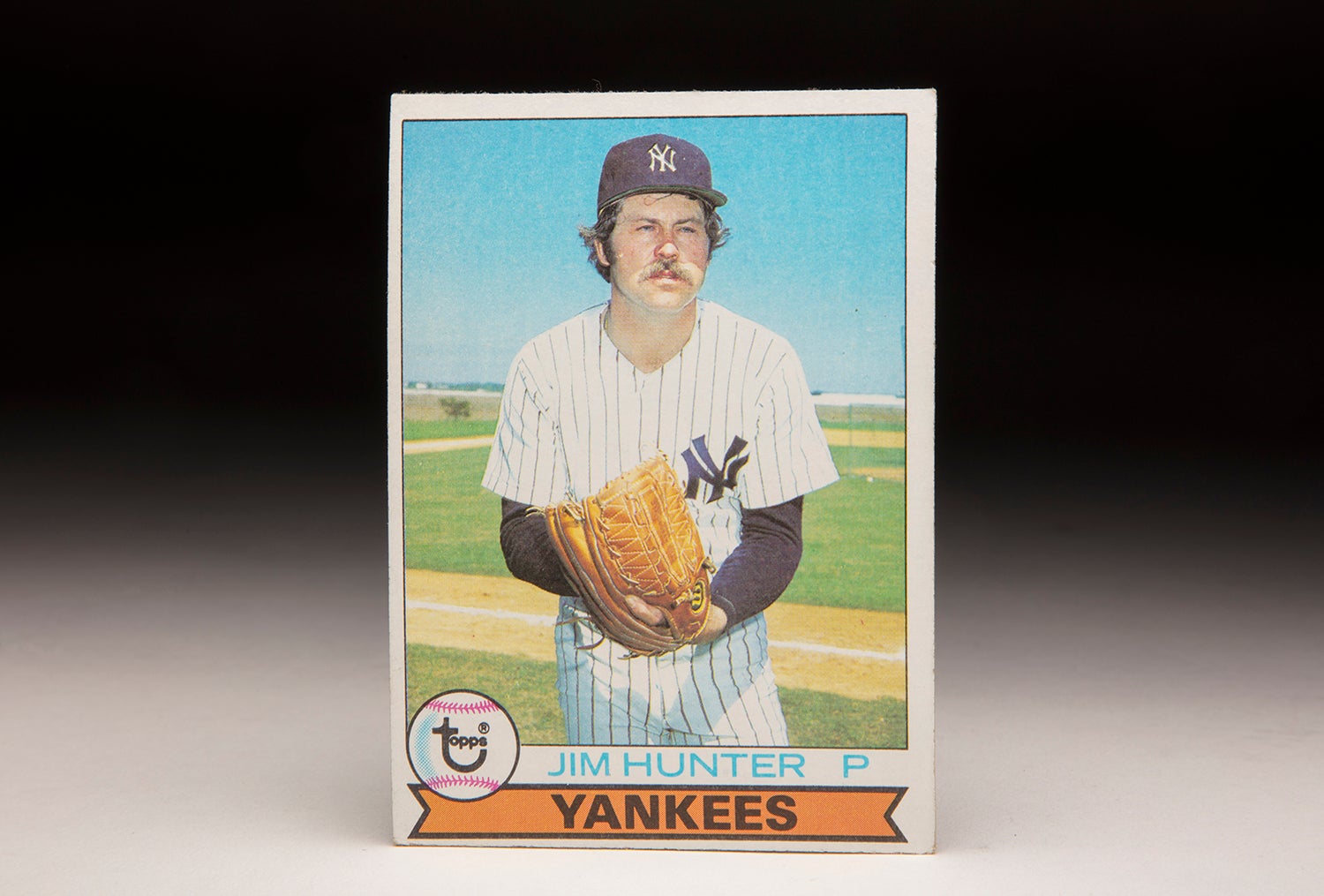

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Jim Hunter

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bud Harrelson

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Gene Tenace

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills