- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1977 Topps Tommy Helms

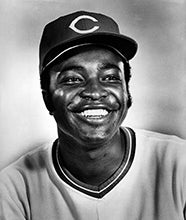

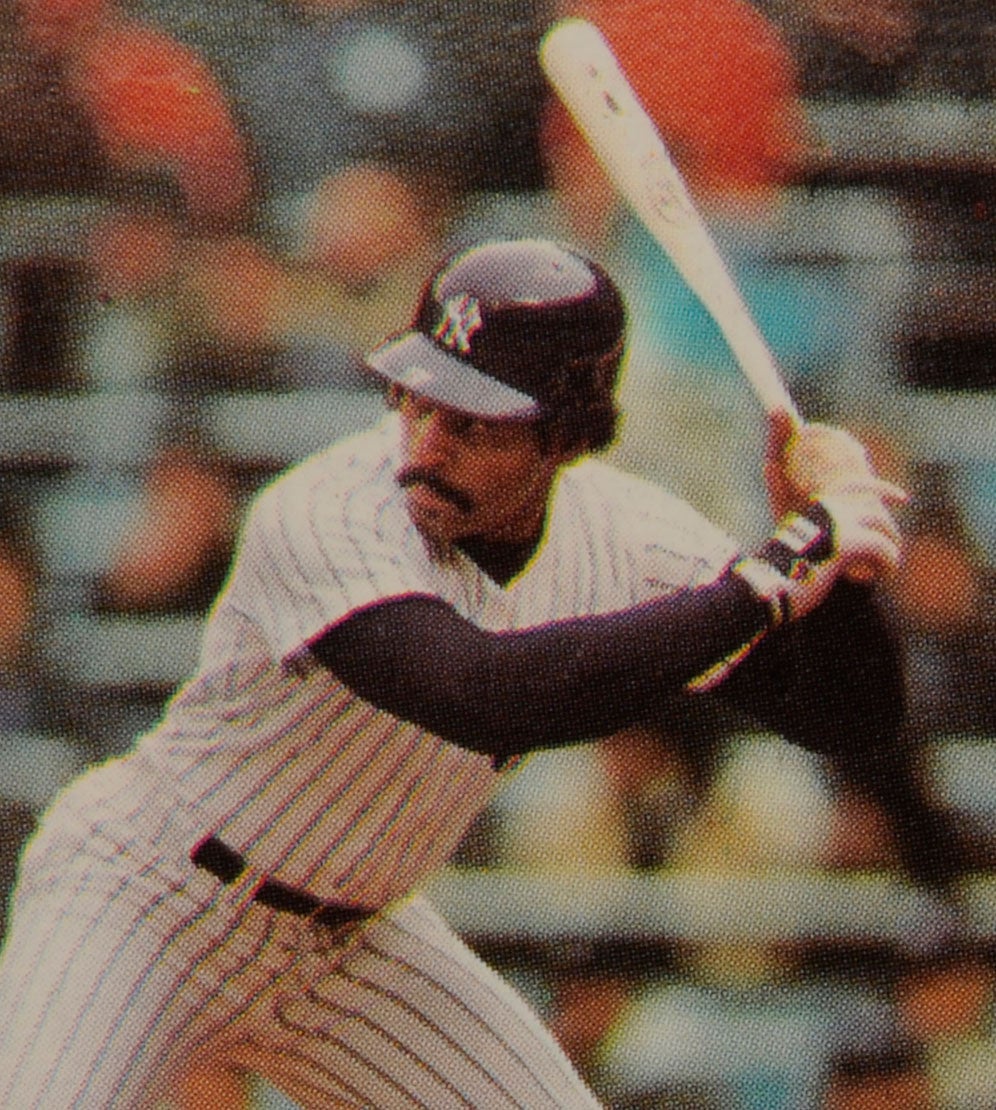

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps Tommy Helms

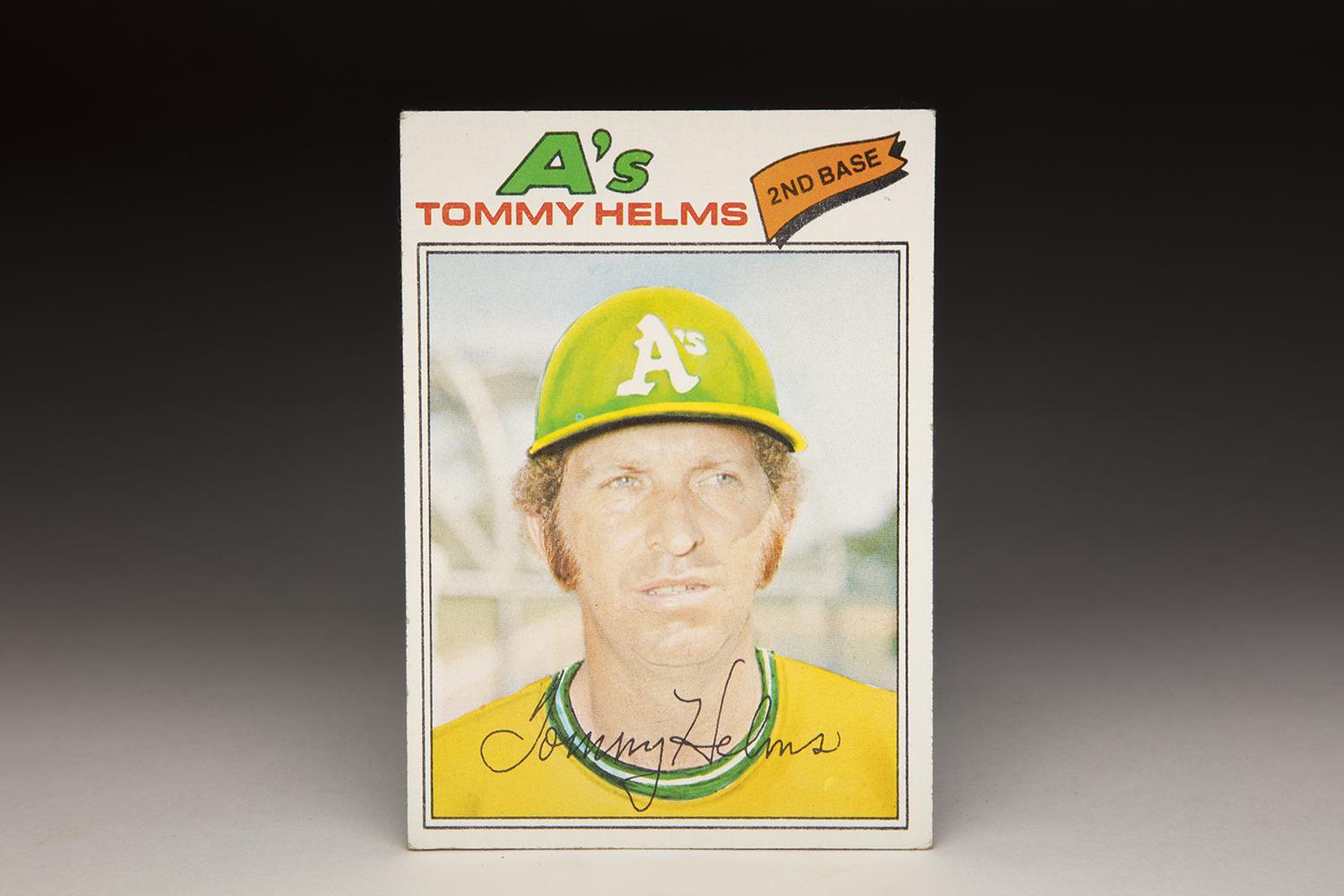

If I had to vote for the most bizarre-looking card in the history of baseball cards, I would be tempted to vote for this one.

Some would prefer to use the words “ugliest card,” but I’d like to be bit more genteel and polite in my observation. Besides, there are cards that probably rank as uglier; at the very least, the 1977 Tommy Helms card has a degree of brilliant gaudiness that makes you look twice, or even three times at it. It’s just so shocking that you feel like you can’t look away, as if what you’re seeing is just not quite possible.

In the past, we’ve noted about examples of airbrushing gone mad on cards. Well, this is airbrushing in a rubber room. In attempting to airbrush Kelly Green (the shade of green preferred by owner/general manager Charlie Finley) onto Helms’ Oakland A’s helmet, the artist at Topps has produced a strange lime green that seems to be specked with yellow highlights. It has almost a kindergarten feel to it. Beyond that, the bill of the helmet is a bright yellow, while the shade of Helms’ jersey is an even brighter yellow, almost to the point of fluorescence.

It’s as if someone plugged Helms’ jersey into a socket and watched it light up like one of Michael Keaton’s outfits in Beetlejuice.

As outrageous as the airbrushing is, the audaciousness of the card is augmented by Helms’ appearance. With his bright red hair, which appears to be permed (at least where it is not covered by the helmet), and with his heavy sideburns, Helms has a look that screams of the 1970s. (When Helms first came up, his hair was as straight as an arrow, but like many players in the mid-1970s, he experimented with a perm.) It was a time for curly hair, Afros, sideburns, mutton chops and pretty much every other form of facial hair. All that Helms is missing is a mustache and a beard, which would have completed the picture of mid-1970s counter-culture brilliance.

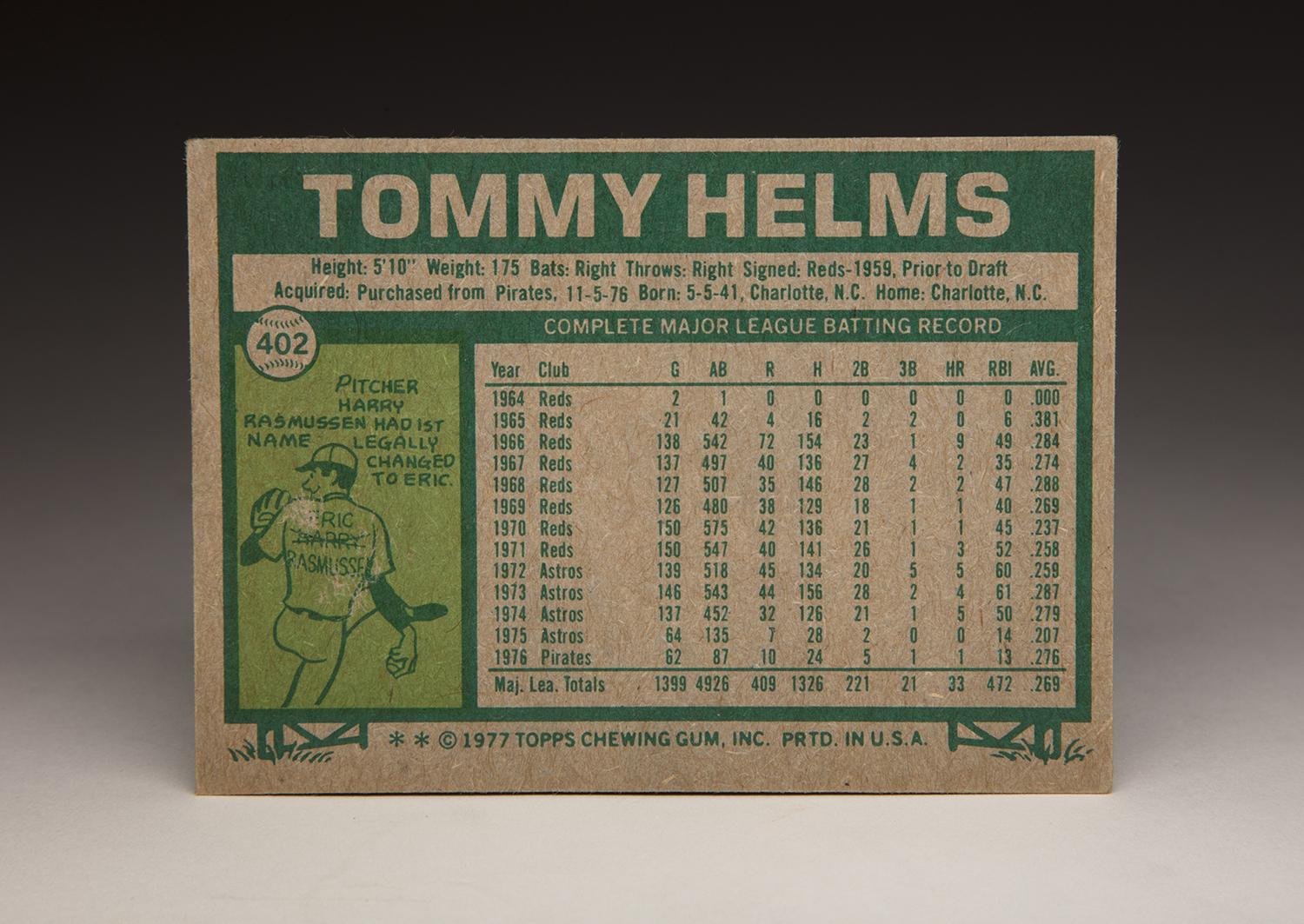

There is more intrigue to this card, too. We see Helms, fresh off a wintertime trade from the Houston Astros, sporting the airbrushed green and gold of the A’s, but he never actually wore the Oakland uniform. Well, at least he never wore the uniform in a regular season game. Helms spent the first half of Spring Training in 1977 with the A’s, but then came the major development of March 15. On that day, the A’s announced a blockbuster deal with the Pittsburgh Pirates, sending Helms, Phil Garner and minor league righty Chris Batton to the Steel City for a gigantic package that included Mitchell Page, Tony Armas, Doc Medich, Rick Langford and Dave Giusti.

So from the time that Helms’ 1977 card hit the shelves, it became obsolete almost immediately. Never playing in a real game for the A’s, Helms would last only slightly longer – 15 hitless games – with the Pirates before he was sent packing again. As a result of the constant motion, he would not appear on a 1978 Topps card wearing the Pirates uniform. Instead, his ’78 Topps card would show him as a member of the Boston Red Sox, the other team that he played for during that wild, fragmented season of 1977.

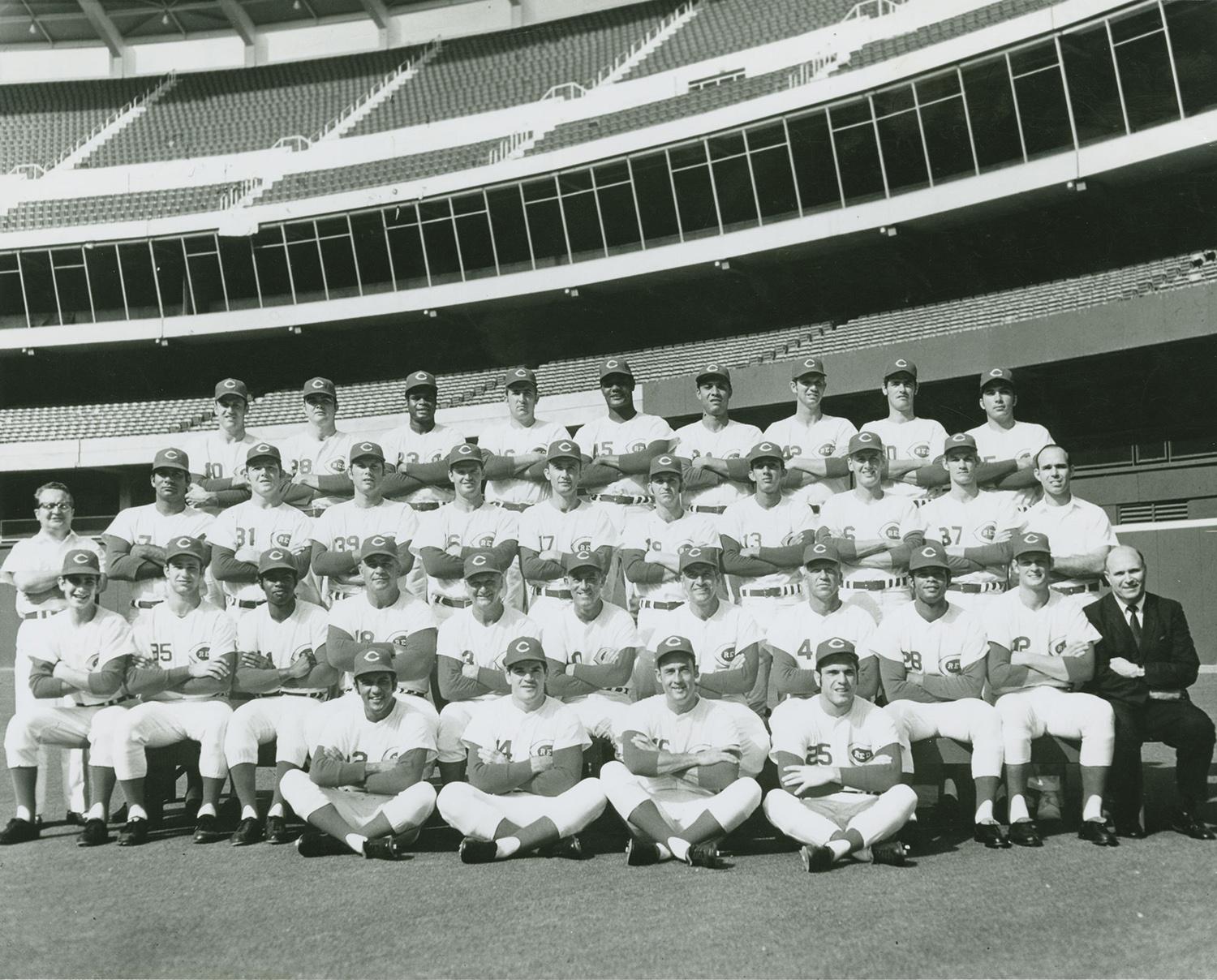

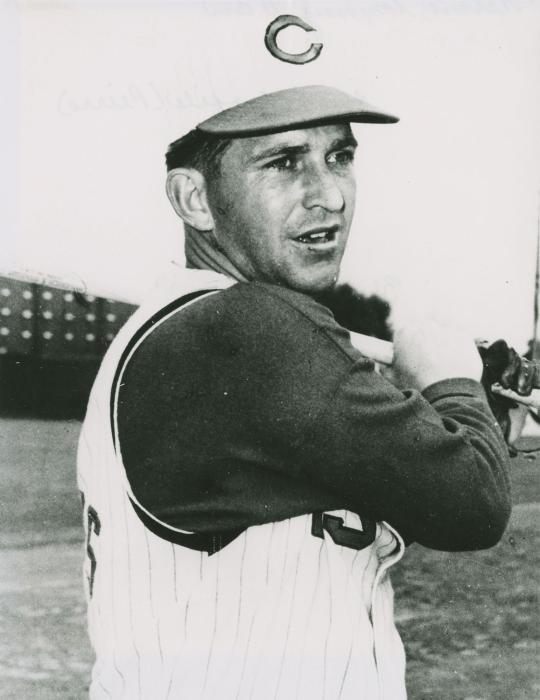

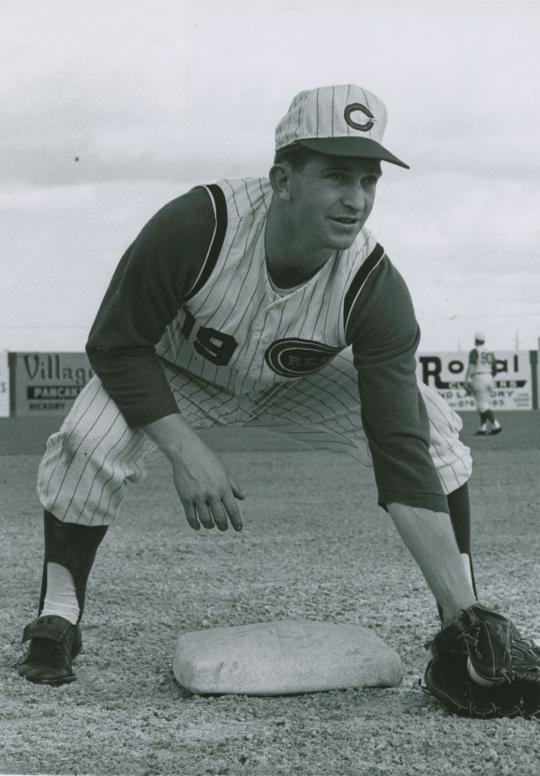

Tommy Helms has become somewhat of an obscure player over time, but at one point, he was a household name. A touted shortstop prospect with the Cincinnati Reds, he earned a cup of coffee with the club in 1964 and then batted .384 over a 21-game stint in 1965. Unfortunately, he was blocked by incumbent shortstop Leo Cardenas, a skilled defender and capable power hitter. In 1966, the Reds initially shifted Helms to second base, but ultimately placed him at third base. Playing the entire season for Cincinnati, he performed well enough to earn National League Rookie of the Year honors.

Though Helms hit only nine home runs, he batted a solid .284, rarely struck out, and gave the Reds dependable defense at third base.

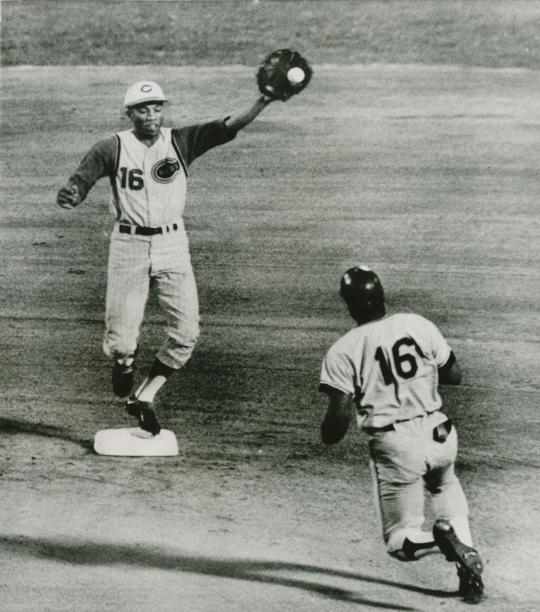

As well as Helms played in 1966, he did not have the ideal profile for a third baseman, where his lack of extra-base power stood out. So in 1967, the Reds shifted him to second base, a position that he was more than capable of handling. Helms’ batting average dropped to .274, but his defensive play was so good that he earned selection to the National League All-Star team.

Over the next four seasons, Helms remained a solid contributor for the Reds, a gritty, hard-nosed player who always remained alert in the field and on the basepaths. He picked up another All-Star Game selection in 1968 and played well in the Midsummer Classic, collecting a double and a walk, and executing several standout plays in the field. That performance earned him praise from his Reds manager, Dave Bristol.

“I couldn’t have been prouder of Tommy if he were my own son,” Bristol told Si Burick of the Dayton Daily News. “He has really worked hard to make himself a star in the field. He’s that rare infielder who bats .300… He has a better concept of second base play than most people think.”

Along those lines, Helms would earn Gold Glove Awards in 1970 and ’71. Though he was not a great hitter, Helms’ ability to make contact and handle the demands of second base made him a valuable player, one who contributed to the Reds winning the pennant in 1970.

The Reds, however, wanted to reconfigure their infield after the 1971 season. They had two players ideally suited to play first base (Tony Pérez and Lee May) and lacked speed and athleticism on the infield. At the December 1971 Winter Meetings, general manager Bob Howsam struck a blockbuster deal with the Astros. The trade sent May, utilityman Jimmy Stewart and Helms to the Astros for a package that included future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, center fielder César Gerónimo and veteran right-hander Jack Billingham.

The trade would work out magnificently for the Reds, but would also deny Helms the chance to become part of the franchise during its “Big Red Machine” heyday. The Reds would win National League pennants in 1972, 1975, and ’76, while taking home world championships the latter two years. It’s difficult to know how successful the Reds would have been with Helms still on the team, but the trade eliminated any chances that he had for further postseason glory.

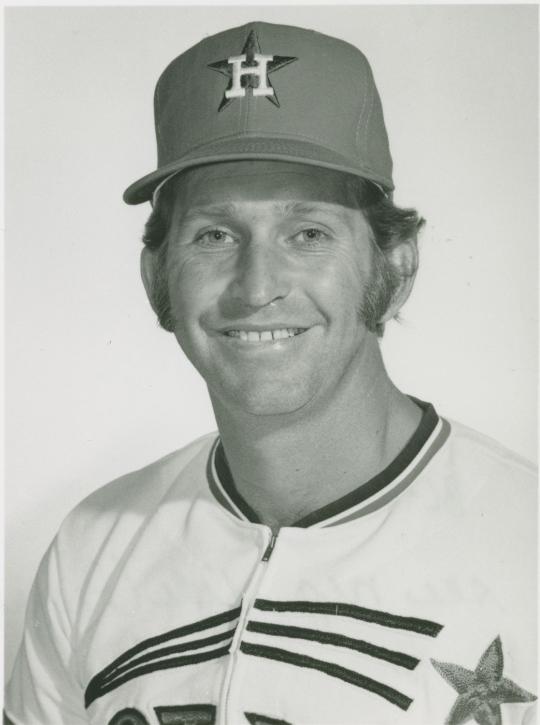

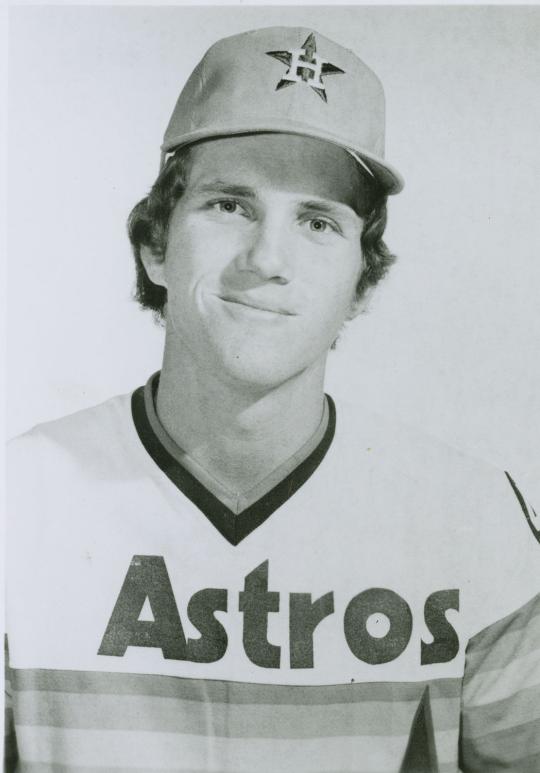

For the better part of the next four years, Helms handled second base skillfully for the Astros. He played reliably, just as he had in Cincinnati, with his best season coming in 1973. Helms hit .287 and struck out only 21 times, while drawing 32 walks. Helms struck out only once for every 27 at-bats, the second best ratio in the National League behind that of Félix Millán. It was a remarkable display of contact hitting in an era when strikeouts were starting to rise.

In 1975, amidst a host of trade rumors, the Astros made him a utility man, with part of his job serving as a backup second baseman to a prospect named Rob Andrews, the younger brother of former Red Sox second baseman Mike Andrews. By season’s end, Helms’ batting average had fallen to .207 and his OPS to .488. Now 34 years old, the Astros believed that Helms had reached the end of the line.

That winter, the Astros traded Helms to the Pirates for a player to be named later, which turned out to be utilityman Art Howe, Vietnam veteran. The Pirates used Helms as a utility player, a role in which the veteran excelled. Filling in at second base, third base, and even shortstop, Helms batted .276 and posted a solid OPS of .741.

Helms did everything the Pirates asked of him, but after the season, the team strangely moved him out. The Pirates sold his contract to the A’s, not even insisting that the A’s compensate them with another player. That transaction laid the foundation for Helms’ shocking 1977 Topps card. By the middle of March, both the Pirates and A’s (specifically Charlie Finley) had changed their minds; Helms headed back to Pittsburgh as part of the aforementioned mammoth nine-man deal.

By the middle of June, the Pirates realized that Helms was not the same player who had played for them in 1976. They released him, but only one week later, the Red Sox came calling. Looking for some depth, the Red Sox used Helms as a DH (which seemed like an odd fit for a singles hitter) and as an occasional backup infielder. He batted .271 in 64 plate appearances, while continuing to make contact and avoid strikeouts at a remarkable rate.

The Sox saw enough from Helms to bring him back for Spring Training in 1978. But a glut of middle infielders made Helms expendable. On March 28, just before the start of a new season, the Red Sox released Helms, bringing to an end his 14-year career.

Helms left baseball to run vending business for a few years, but returned to the game as one of Don Zimmer’s coaches with the Texas Rangers in 1981. Two years later, Helms returned to Cincinnati, this time as a first base coach and infield instructor. He remained on the staff for the better part of the decade, working in relative anonymity.

And then in 1989, Helms found himself thrust into the spotlight. When Reds manager Pete Rose settled with Commissioner Bart Giamatti on a lifetime ban for his involvement with gambling, the Reds called on Helms as his replacement – on an interim basis. It was an especially awkward situation for Helms, given his close relationship with Rose, his former teammate. “This is a very, very sad day for me,” Helms told the Associated Press.

Managing the Reds for the remainder of the season, the popular Helms instilled some order and discipline to the Cincinnati clubhouse. He also received endorsements from several of the team’s veterans, including Dave Collins, Eric Davis, and Paul O’Neill. They all called upon the Reds to give Helms the job for 1990. Owner Marge Schott ultimately announced that she would not bring him back as manager, instead opting for a higher profile hiring in Lou Piniella. Furious with Schott, Helms vowed never to work for the Reds again, as long as she remained as the owner.

After his parting from Schott, Helms did some work as a minor league manager in the early 1990s. He left baseball again, before returning to do some independent league managing in 2000 and 2001.

Helms passed away on April 13, 2025, but for fans of card collecting, the mention of his name will always bring a smile to our faces, thanks to that wonderfully weird card from 1977 Topps.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

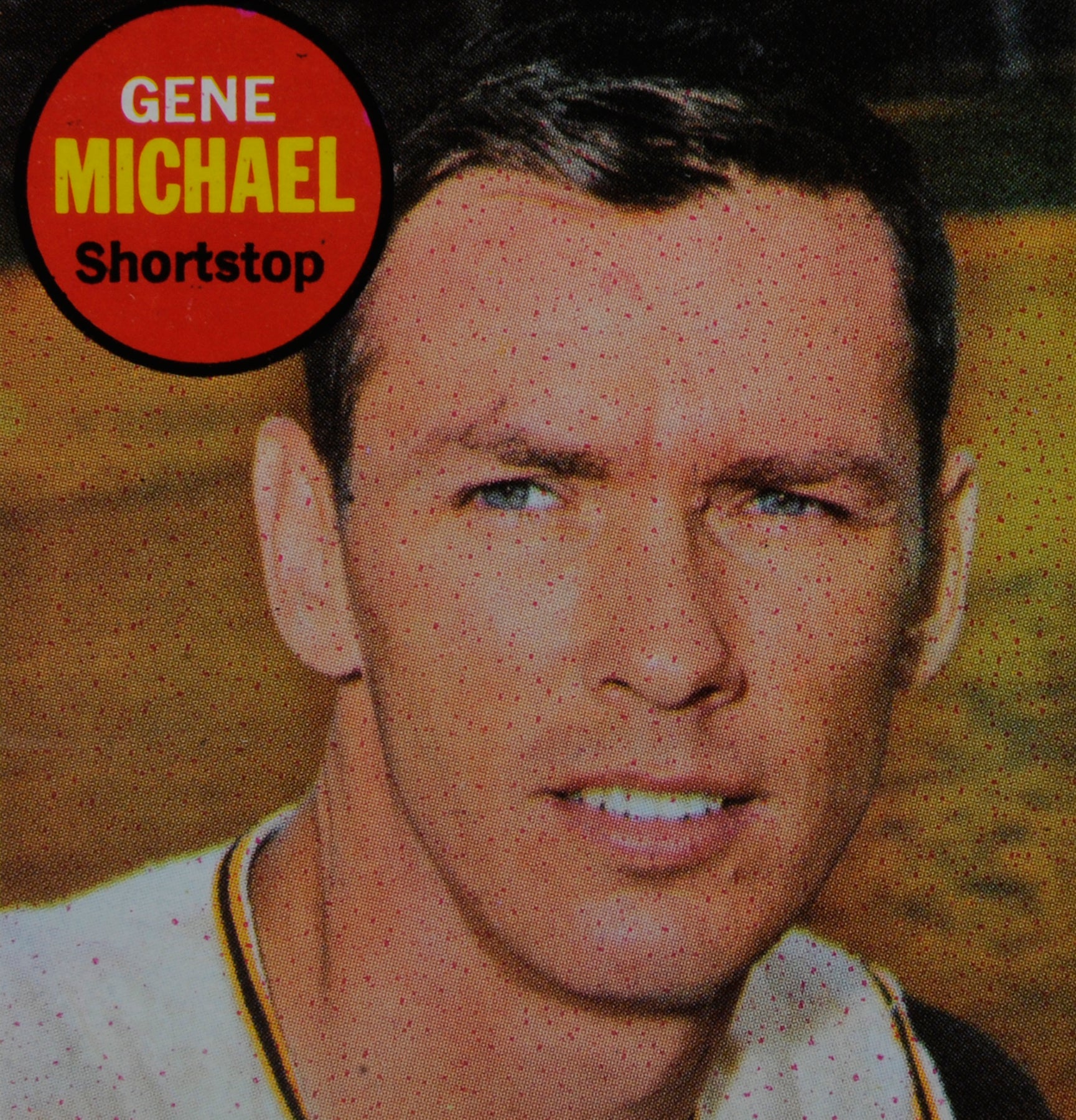

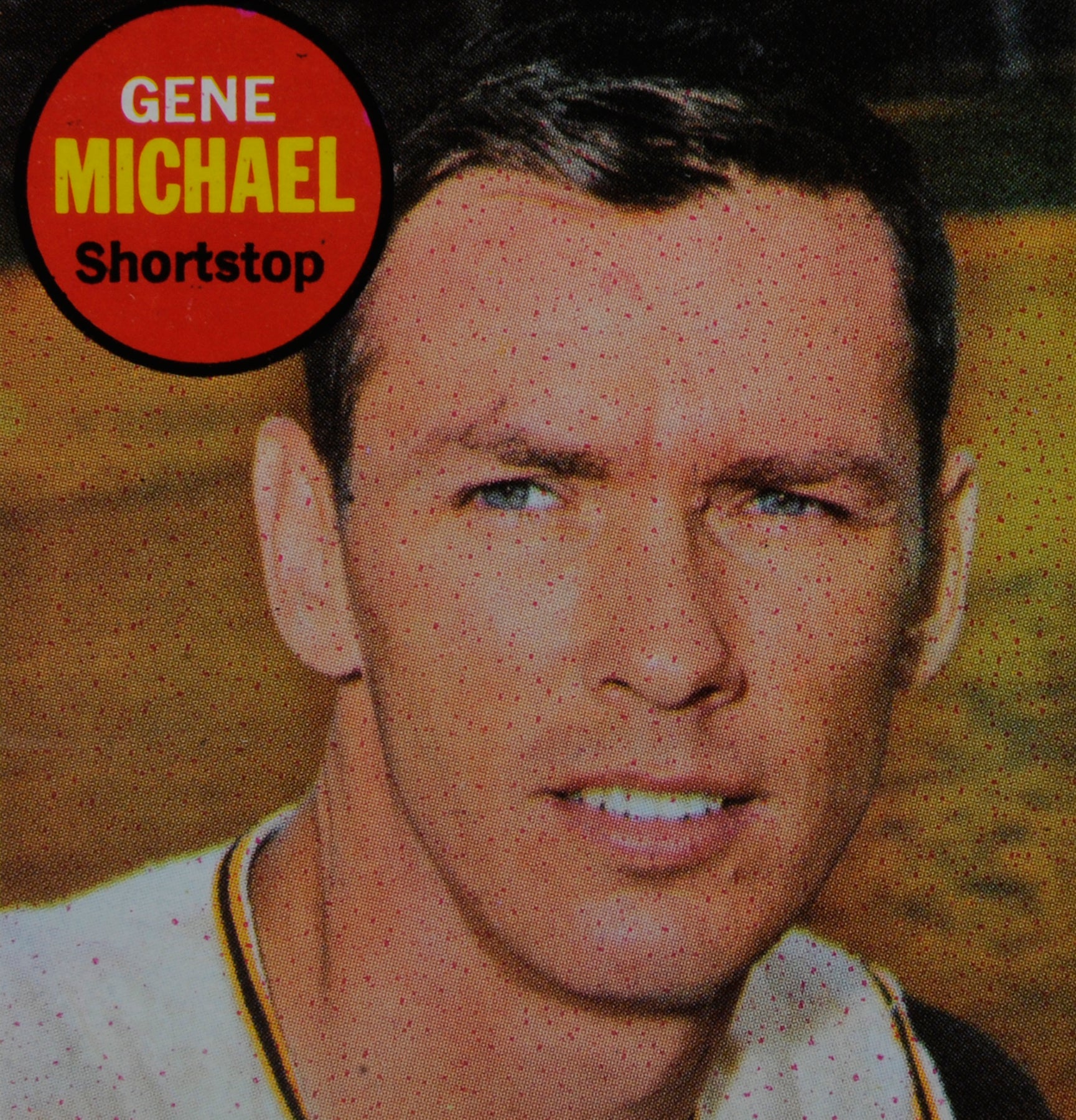

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Rawly Eastwick

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Toby Harrah