- Home

- Our Stories

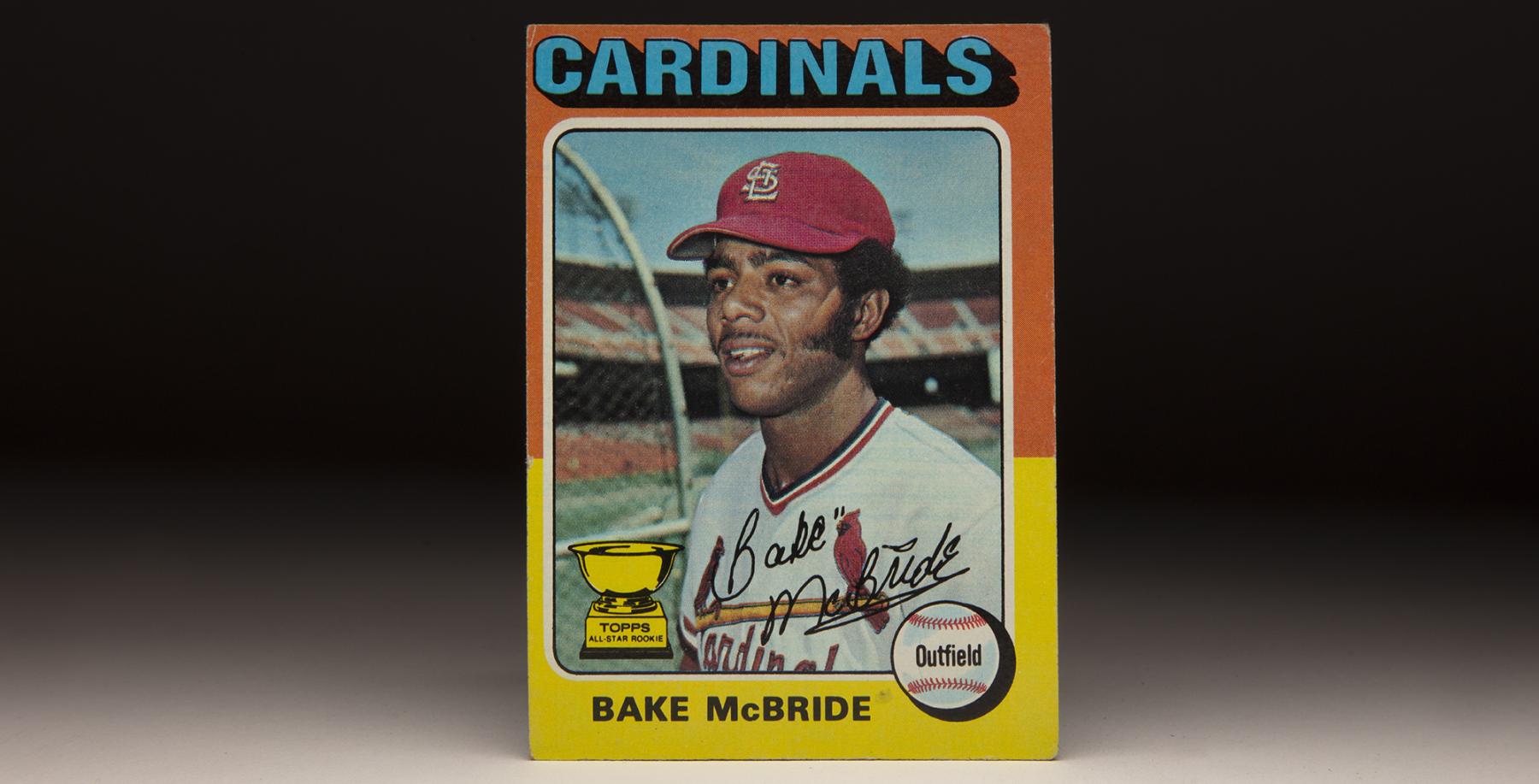

- #CardCorner: 1975 Topps Bake McBride

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Bake McBride

When the baseball gods are on your side, the strangest stat lines often appear.

Such was often the case with the talented Arnold “Bake” McBride.

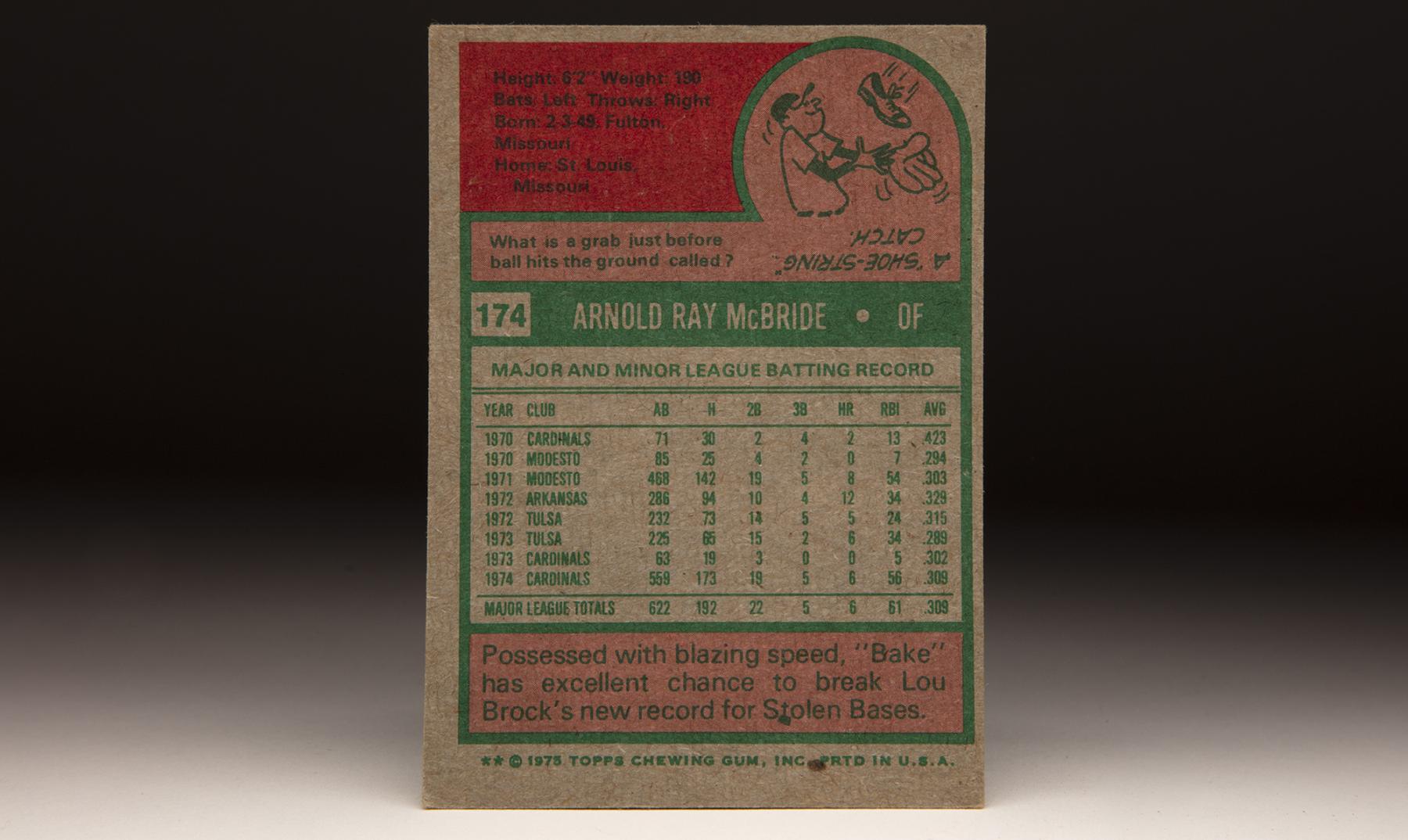

Born Feb. 3, 1949, in Fulton, Mo., McBride was a standout high school athlete in virtually every sport except baseball – because his high school did not field a team. His first love was track and field, but his speed was jeopardized when he broke a bone in his left ankle grabbing a rebound during a high school basketball game in 1967.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Given a prognosis that included the possibility that he would never again be able to run competitively, McBride worked his way back continued to play a variety of sports at Westminster College in Fulton, but dropped out following his second year. His athleticism, however, kept him active, and McBride – a cousin of 11-year NFL running back Tony Galbreath – continued to be on the radar of pro teams, including the NBA’s Phoenix Suns, which offered him a tryout.

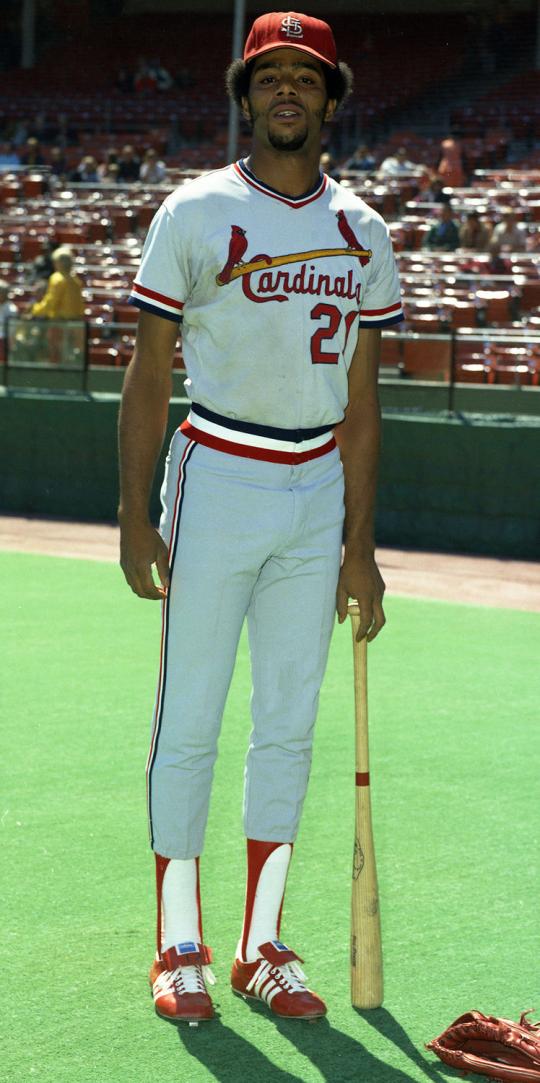

But after impressing the St. Louis Cardinals at an open tryout camp, he was selected by the team in the 37th round of the 1970 Major League Baseball Draft. The left-handed hitting McBride then tore through the minor leagues, hitting .353 at two levels in 1970, .303 with 40 stolen bases for Class A Modesto in 1971 and .322 at Double-A Arkansas and Triple-A Tulsa in 1972.

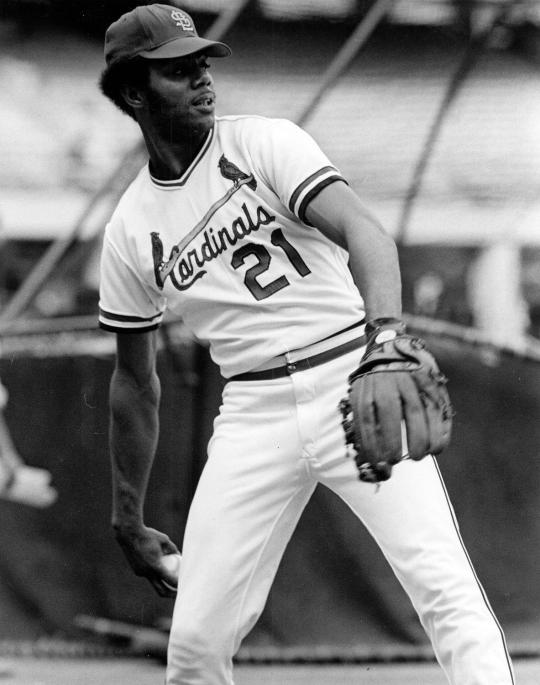

After some more seasoning at Tulsa in 1973, McBride debuted with the Cardinals on July 26, 1973 – earning the chance to wear No. 21, the number of Cardinals legendary center fielder Curt Flood.

McBride grounded out in his first at-bat after entering the game against the Mets in place of Lou Brock, but later singled home Ken Reitz for his first hit and RBI.

“I was a little nervous the first time up,” McBride told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “But I was comfortable the second time.”

In 1974, McBride won the job as the Cardinals’ center fielder with a sensational spring and hit .309 with 30 steals, 81 runs scored and 56 RBI over 150 games. And late in the season, he wrote his name into the record books in a game that started on Sept. 11, 1974, at New York’s Shea Stadium.

After Reitz homered to tie the game at 3 with two outs in the top of the ninth, the team’s played on into the early morning hours. In the top of the 25th inning, McBride singled to lead off the inning but looked to be picked off when pitcher Hank Webb caught him flat-footed at first base. But Webb’s throw was off target and caromed down the right field line, allowing McBride to score all the way from first when he ran through third base coach Vern Benson’s stop sign and scored as Mets catcher Ron Hodges dropped the throw.

At seven hours and four minutes, it was the longest night game in big league history – with the game ending at 3:12 a.m. local time. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and his wife, sitting in box seats near the Mets dugout, stayed for the entire contest.

When asked if McBride would be fined for running through the stop sign, Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst told the Post-Dispatch: “Bake was running so fast that he couldn’t see the sign. When you’ve got speed like McBride’s, you make the other guys nervous. You just can’t beat that speed.”

McBride, who was 4-for-10 in the marathon game, earned the Baseball Writers’ Association of America’s National League Rookie of the Year Award following the season – earning 16 votes compared to seven for runner-up Greg Gross of the Astros.

Gross, however, won the NL rookie award given by the Sporting News, which was based on a poll of players.

“I was a little upset about that; I was cussing,” McBride told the Post-Dispatch.

For the first of several of his 11 big league seasons, McBride battled injuries in 1975. A shoulder problem plagued him early and ankle bruises hindered him late, limiting McBride to 116 games. He hit .300, however, and managed to steal 26 bases.

Then in 1976, McBride was hitting .335 on Aug. 3 – having been named to his first All-Star Game the month before – when the Cardinals ended his season so he could have surgery on his left knee.

“I don’t even know how I did it,” McBride told the Post-Dispatch. “It just started hurting. It got worse and worse. It got to the point where it was unbearable.”

Bill Madlock won the NL batting title with a .339 mark, meaning McBride would have had a real chance at the crown had he remained healthy.

“Bake had a bum rap attached to him,” said Cardinals teammate and future Hall of Famer Lou Brock. “I was hearing that he only played when he felt like it and all that stuff. I’ve seen him in the outfield when he never should have been in uniform.”

Then, after a slow start to the 1977 season when he clashed with new Cardinals manager Vern Rapp, McBride was traded to the Phillies with Steve Waterbury in exchange for Rick Bosetti, Dane Iorg and Tom Underwood. It was a deal that put McBride on a team that would be one of the National League’s best for the next several years.

“Bake will add another dimension to the ball club,” Phillies general manager Paul Owens told the Associated Press.

With topflight defender Garry Maddox in center field, the Phillies moved McBride to right. He caught fire in the season’s final two months, hitting .358 with 16 stolen bases while helping the Phillies win their second straight NL East title. Philadelphia lost to Los Angeles in the NLCS, but McBride stamped himself as part of the Phillies’ future with a .339 average in 85 games for Philadelphia that year.

McBride slumped to a .269 average in 1978, the first time he failed to hit .300 in the big leagues. He didn’t crack the .300 mark in 1979, either, but proved his durability by playing in 151 games and hitting .280 with 12 triples, 12 homers 60 RBI and 25 stolen bases.

Then in 1980, the stars aligned for a Phillies team that had never won a modern World Series title. Philadelphia captured the NL East title for the fourth time in five seasons, and this time advanced to the World Series by beating Houston in the NLCS.

McBride hit .309 in 137 games, driving in a career-best 87 runs despite hitting just nine home runs. The 87 RBI would mark more than 20 percent of his career total of 430 RBI over 11 big league seasons.

Then in the World Series, McBride – bucking his season trend – homered in Game 1 against the Royals, a three-run shot in the third inning that helped turn a 4-0 Kansas City lead into a 5-4 Philadelphia advantage.

The Phillies eventually won the game 7-6, with McBride adding two singles following his home run.

“Bake’s home run crushed it for me,” Phillies manager Dallas Green told the Associated Press. “He’s been that kind all year…a clutch RBI guy.”

McBride hit .304 in the Phillies’ six-game victory, forever etching himself into Phillies’ lore. It would be the highlight of a career that would feature just 155 more games in his final three seasons as he again suffered through long stints on the disabled list.

McBride batted .271 in 58 games in the strike-shortened season of 1981, helping the Phillies advance to the postseason before losing to Montreal in the NLDS. Then on Feb. 16, 1982, the Phillies traded McBride to the Indians in a deal that brought reliever Sid Monge to Philadelphia.

At the time of the trade, only six active National League outfielders topped McBride’s career .298 batting average.

But McBride played only 27 games in 1982 while battling an eye infection, hitting .365 but not appearing in a game after May 21. A contact lens user since the early 1970s, McBride’s vision problems did not clear up until after the season.

“Since May 27, I’ve gone to the doctor every day except Sundays,” McBride told the Akron Beacon Journal in June. “Besides that, the only thing I do is go crazy.”

McBride’s career average stood at .29975, or .300 when rounded up, following the 1982 season. He hit a respectable .291 in 70 games in 1983 for Cleveland, but shoulder and thumb injuries limited his playing time.

A free agent following the season, McBride found limited opportunities and played 32 games with the Rangers’ Triple-A team in Oklahoma City in 1984 before ending his career with a .299 batting average, 1,153 hits, 548 runs scored and 183 stolen bases.

But in only 11 big league seasons, McBride captured the baseball spotlight on a regular basis.

“When I was drafted so low, I knew I would have a chance to prove myself,” McBride told United Press International. “I think I did.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

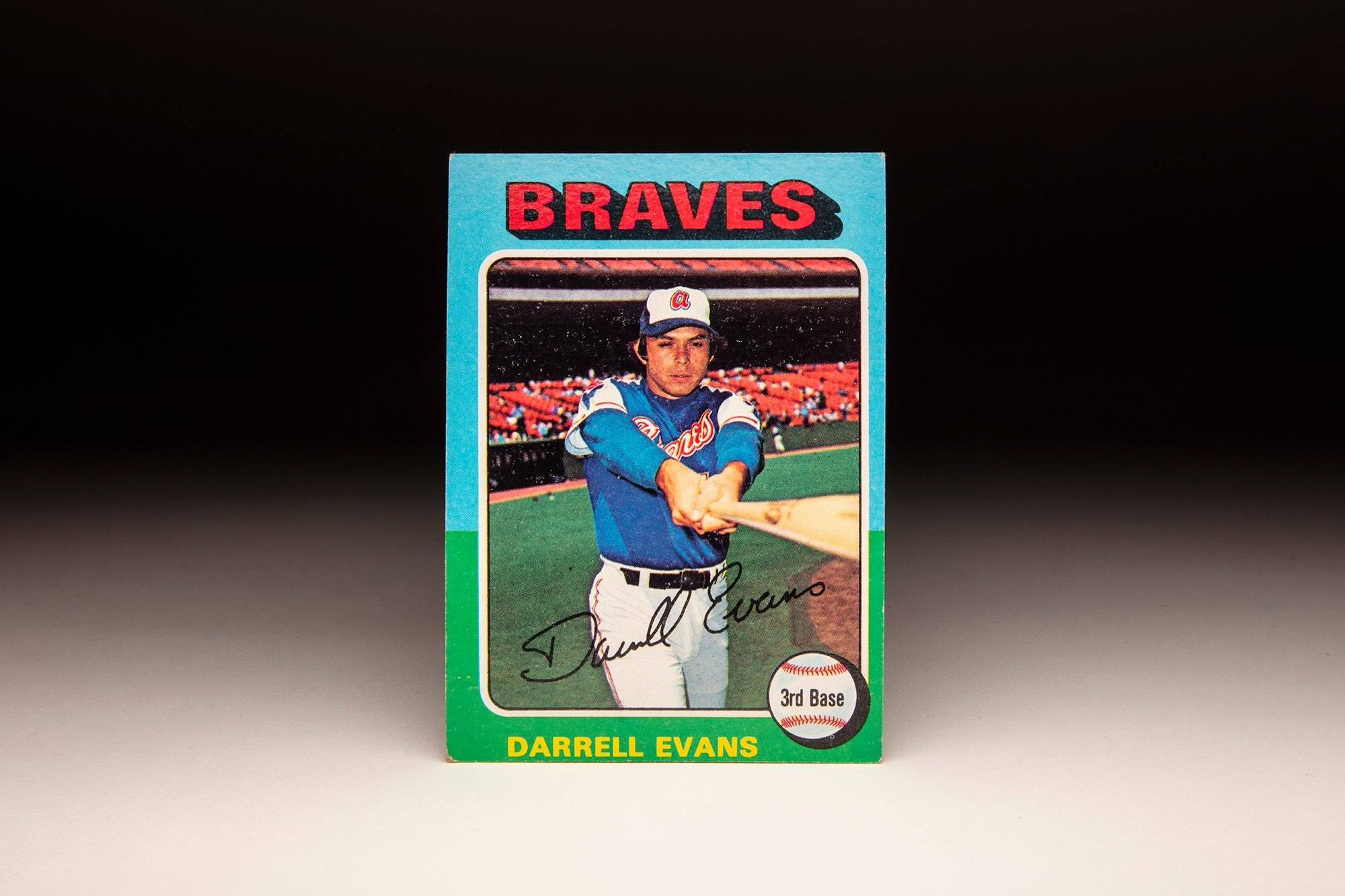

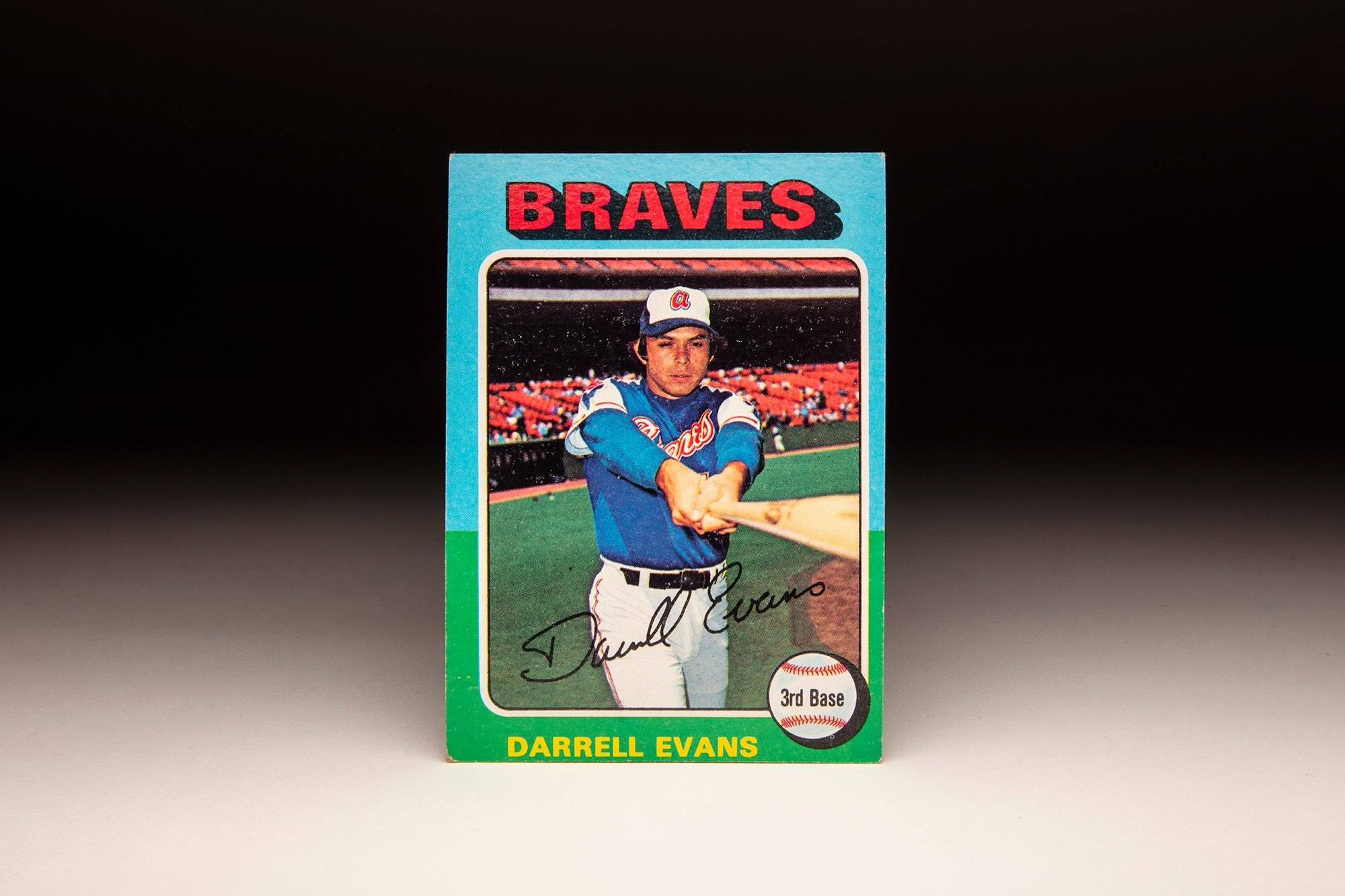

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Darrell Evans

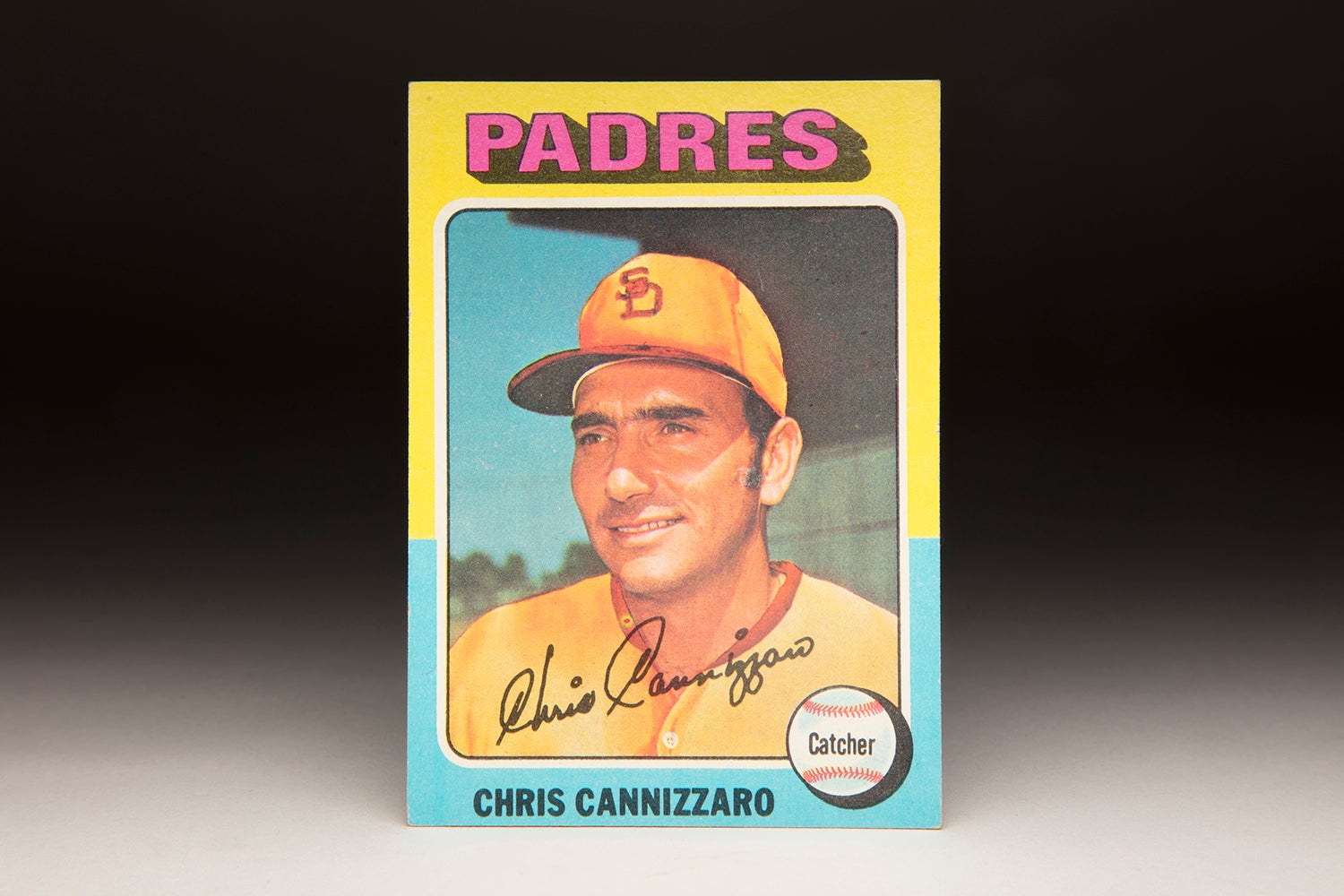

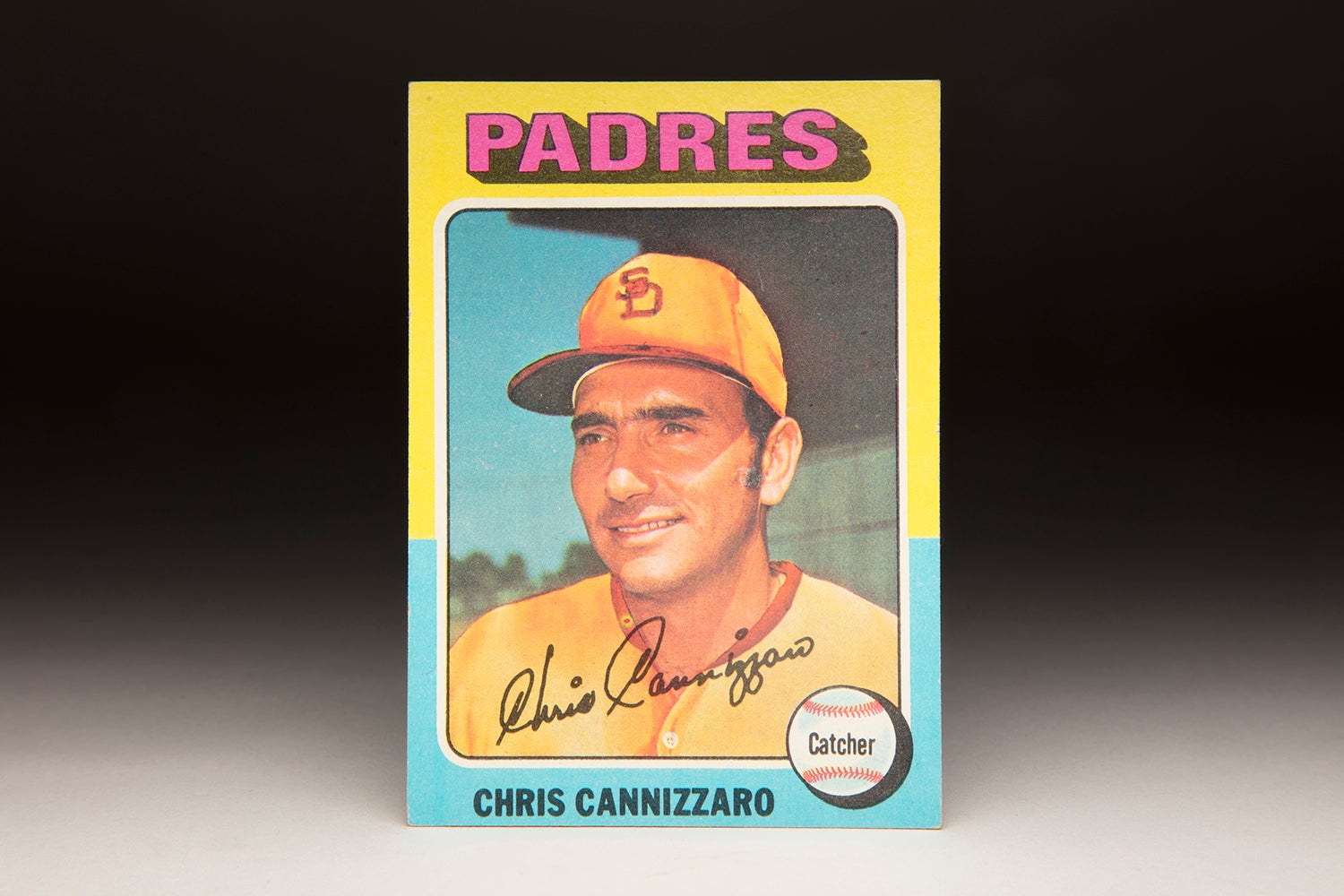

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Chris Cannizzaro

Former pinch-hitting specialist Greg Gross enjoys history at Hall of Fame

#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Darrell Evans

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Chris Cannizzaro

Former pinch-hitting specialist Greg Gross enjoys history at Hall of Fame