- Home

- Our Stories

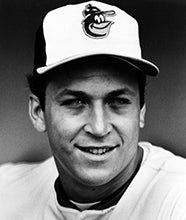

- #CardCorner: 1970 Topps Mark Belanger

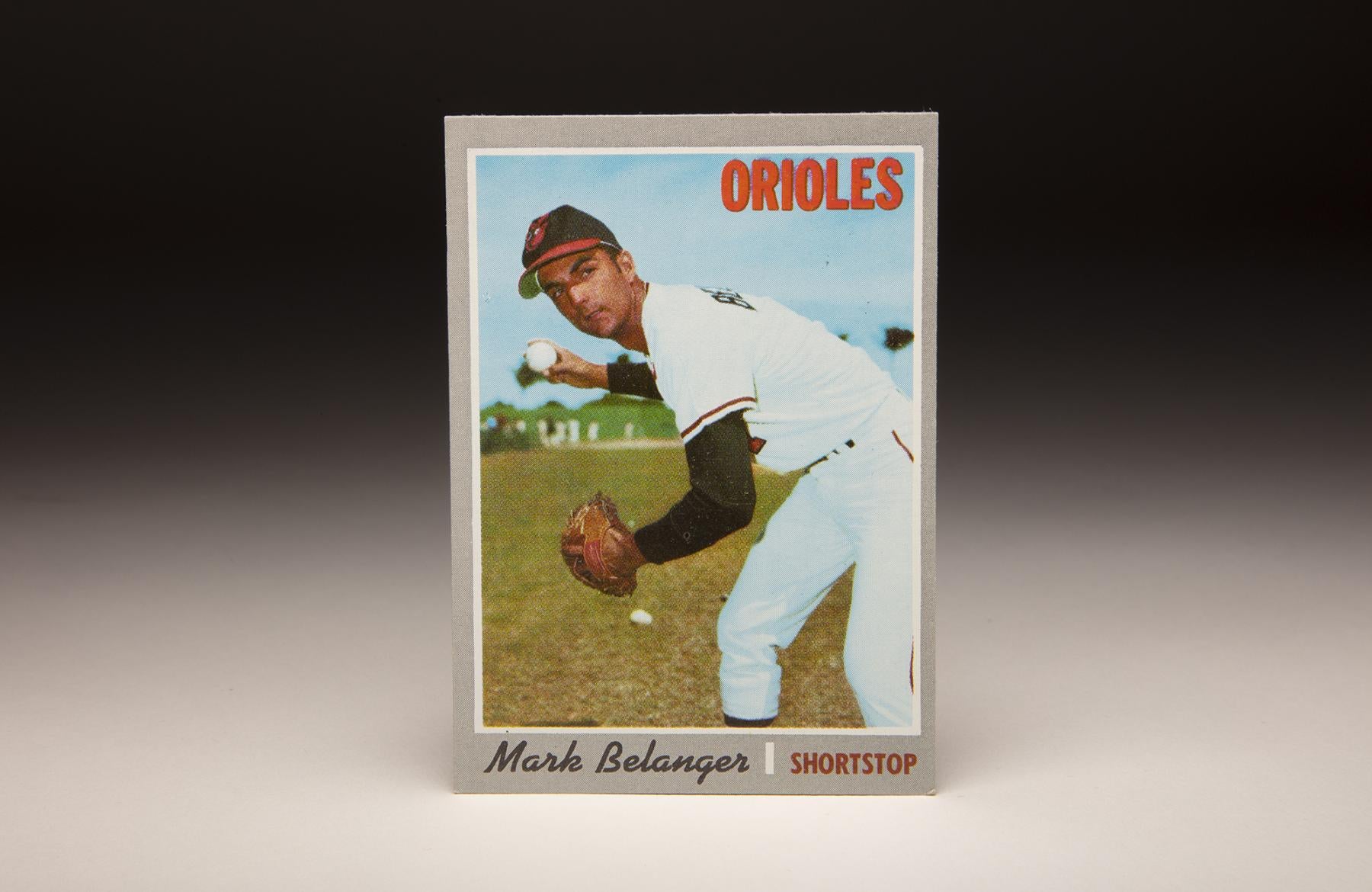

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Mark Belanger

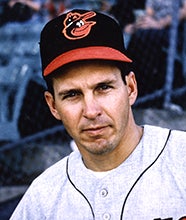

Mark Belanger inspired a million “what if” arguments in the 1970s, as fans wondered how big a star Belanger would have been if he could have hit better than his .228 career batting average.

But that debate missed the point. Belanger was the shortstop of one of the greatest teams of his era, won eight Gold Glove Awards and earned the respect of future Hall of Famers.

There’s not much more anyone could accomplish in the game.

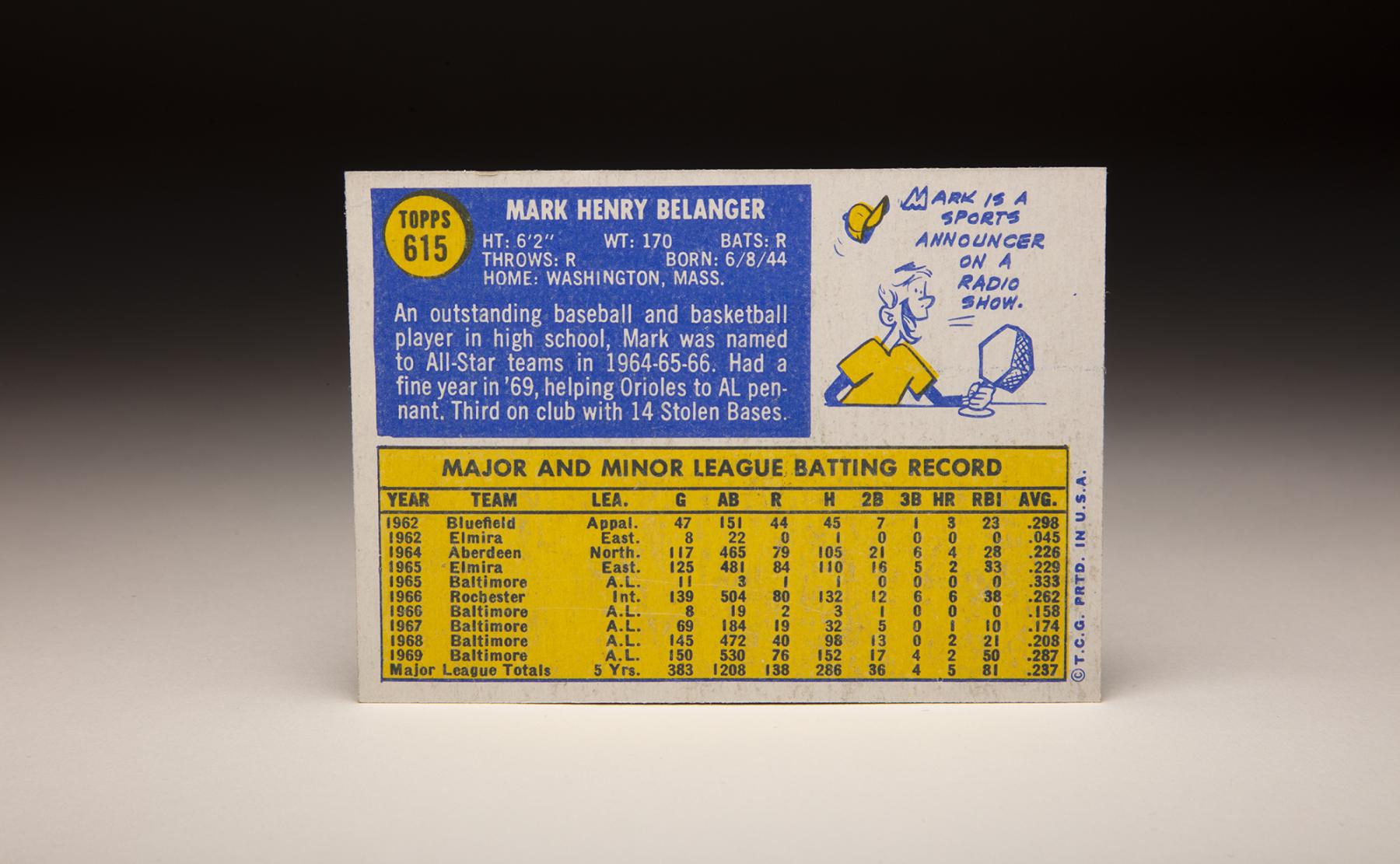

Born June 8, 1944, in Pittsfield, Mass., Belanger starred in baseball and basketball at Pittsfield High School, leading his roundball team to the Western Massachusetts title in 1962. He accepted a full athletic scholarship to the University of Connecticut, following in the footsteps of his brother, Al, who was a left-handed pitcher.

But when the Baltimore Orioles offered Belanger a bonus worth a reported $35,000, Belanger signed a baseball contract and was sent to Class D Bluefield of the Appalachian League. He hit .298 in 41 games with Bluefield, earning an All-Star berth and impressing the Orioles’ brass enough to earn a promotion to Class A Elmira late the in season.

At 6-foot-1 and 170 pounds, Belanger earned the nickname that would follow him for his entire career: The Blade.

After playing in the Florida Winter Instructional League following the season, Belanger enlisted in the Air National Guard and missed the entire 1963 season. But the move gave the Orioles some roster flexibility in the wake of Belanger’s bonus, which would have forced Baltimore to carry Belanger on the active roster had it not been for his time in the service.

In 1964, Belanger played for the Class A Aberdeen Pheasants of the Northern League, hitting just .226 but compiling a .357 on-base percentage and showing off his big league-ready glove while again earning All-Star notice.

In 1965, Belanger hit .229 with an Eastern League-leading 29 stolen bases for Double-A Elmira while playing for future Orioles skipper Earl Weaver.

“I’m hitting in streaks this season,” Belanger told the Elmira Star-Gazette in July. “I’ve had some good days and some other days not so good. But I’m not worrying about my hitting. I’m concentrating on my fielding. My goal is to get as close to perfection as I can get.”

Then in August, future Hall of Famer Luis Aparicio – then in his third season as the Orioles’ shortstop – contracted the mumps and was sidelined. The Orioles called up Belanger, who debuted on Aug. 7 and appeared in seven games as a defensive replacement and pinch runner before being returned to Elmira Aug. 17.

“I realize the only reason I’m up there is because Aparicio is ill and Davey Johnson (the Orioles’ prized shortstop prospect at Triple-A Rochester) broke his hand,” Belanger told the Star-Gazette after the Orioles traveled to Elmira for an exhibition game a few hours after Belanger was called up. “I just hope I can impress them enough to warrant another chance some time.”

Belanger did – and he was recalled to Baltimore in September, recording his first big league hit on Sept. 10 off the Athletics’ Don Mossi. The Orioles sent Belanger to Rochester to start the 1966 season, where he once again played for Weaver. He hit .262 with 19 steals and 80 runs scored for the Red Wings, then played in eight late-season games for the Orioles as Baltimore won its first American League pennant.

Belanger did not appear in the Orioles’ World Series sweep of the Dodgers, but he was already earmarked as the team’s shortstop of the future.

“Our scouts say he’s not only ready now for the majors, but if he were to come up and hit .264 he couldn’t help being the All-Star shortstop,” Orioles farm director Lou Gorman told the Baltimore Sun following the 1966 season when Belanger won Rawlings’ Silver Glove Award as the top defensive shortstop in all of Minor League Baseball. “Other organizations just rave about Mark and his defensive ability.”

Belanger made the Orioles’ roster to start the 1967 season but was on the bench for long stretches as Aparicio and Johnson (who had moved to second base) received most of the playing time. In 69 games, Belanger hit .174 but flashed the leather by making only nine errors in 247 chances at shortstop, second base and third base.

Following the 1967 season, Aparicio was traded to the White Sox – opening the position for Belanger. But Belanger’s Air National Guard unit was activated on April 11, and for several days it looked like the outfit might be deployed to Vietnam. The deployment never occurred, however, and Belanger missed only the first three games of the 1968 season before taking over at shortstop. In 145 games that season, he hit .208 with 21 RBI and a .248 slugging percentage. But Belanger excelled in the field, posting a 4.4 Defensive WAR that was the best for any big league shortstop since 1917 and trailed only teammate Brooks Robinson (who had a 4.5 Defensive WAR at third base) at any position in the majors.

That year’s Gold Glove Award went to Aparicio. But Belanger proved that the advance notices about his glove work were not exaggerated.

More importantly, Weaver replaced Hank Bauer as Orioles manager midway through the 1968 season. It was the beginning of a Baltimore dynasty that Belanger anchored with his nearly unparalleled defense.

In 1969, Belanger produced what would be the best season of his career offensively – hitting .287 in 150 games with 76 runs scored, 14 stolen bases and 50 RBI. His average was .303 as late as May 4, and – working with Orioles hitting coach Charlie Lau – Belanger cut down on his strikeouts (going from 114 in 1968 to 54 a year later) and focused on hitting the ball on the ground by using a heavier bat.

“Charlie had me close my stance,” Belanger told the Associated Press. “And he keeps reminding me to keep my left shoulder going into the ball.

“I’m going for 140-foot drives over the infield, not over the fences.”

Belanger’s fielding was as spectacular as ever that season, and the Orioles won an incredible 109 games before sweeping the Twins in the first ALCS. But in the World Series, the Mets shocked Baltimore in five games with an epic upset.

In 1970, the Oakland A’s hired Lau away from the Orioles – and Belanger’s offense suffered. His batting average dropped to .218 and his run scored (53) and RBI (36) totals also dropped, but the Orioles repeated as American League champions. Defensively, Belanger did not repeat his Gold Glove Award from 1969 – Aparicio won the award for the ninth-and-final time that year – but Baltimore took home the ultimate prize by winning the World Series against the Reds.

Belanger’s leaping catch of Tony Pérez’s sixth-inning line drive in the decisive Game 5 would have been a defensive highlight for the Orioles if not for Brooks Robinson’s legendary performance throughout the Fall Classic – one that earned him Most Valuable Player honors.

In 1971, Belanger hit .266 and even drew 73 walks to push his on-base percentage to a career-best .365. He won his second Gold Glove Award as the Orioles captured their third straight AL pennant, but Baltimore was denied back-to-back World Series wins when the Pirates defeated the Orioles in seven games.

With highly touted prospect Bobby Grich – fresh off a 32-homer season for Triple-A Rochester – ready for the big leagues in 1972, Weaver faced the problem of finding at-bats for three middle infielders in Belanger, Johnson and Grich. Weaver played Grich in 81 games at shortstop that season, relegating Belanger to a part-time role that saw him hit .186 in 113 games. Grich was named to the AL All-Star team, and following the season – one which saw the Orioles finish out of first place for the first time since 1968 – Baltimore traded Johnson to the Braves.

Weaver quickly reinstalled Belanger at shortstop.

“Belanger’s got unbelievable range,” Weaver told the Miami Herald. “It looks like the damn ball slows up and waits for him to get there. Range-wise, as far as going left or right laterally to get the ball, I don’t think Belanger can be touched.”

Belanger hit just .226 in 154 games in 1973 but led all AL shortstops in assists with 530 and helped Baltimore reclaim the AL East title. Oakland, however, beat the Orioles in the ALCS was Belanger went 2-for-16 in five games.

The 1974 season looked very much like 1973 as Belanger hit .225 in 155 games, won another Gold Glove, led the league in assists (552) and also topped all AL shortstops in fielding percentage (.984) for the first time. The Orioles once again won the AL East and again lost to Oakland in the ALCS.

The Orioles and Belanger could not have known it, but they would not return to the postseason again until 1979. But Belanger continued to set the standard for defensive shortstops, leading the league in assists in 1976 and in fielding percentage in 1977 and 1978.

From 1973-78, Belanger’s Defensive WAR never dropped below 3.4 and topped out at an incredible 4.9 in 1975.

Belanger even hit .270 in 1976 and earned his only All-Star Game selection.

“I think lack of aggressiveness has been my biggest shortcoming in the past,” Belanger told the Cumberland Sunday Times in 1976 when his batting average ranked third among Orioles regulars. “The more you bat and the more successful you are, the relaxed and confident you become.”

But the offensive success would not last. Belanger hit just .206 in 1977 and .213 in 1978 as Weaver regularly pinch-hit for Belanger in tight spots. He won his eighth-and-final Gold Glove Award in ’78 but lost significant playing time to Kiko Garcia the following year as Baltimore returned to the World Series.

Belanger hit just .167 in 101 games in 1979 and was 0-for-6 in five World Series games as the Orioles lost to Pittsburgh.

Belanger and Garcia shared the shortstop job in 1980 as each endured long slumps, with Belanger hitting .228 in 113 games in a season where he turned 36 years old. In 1981, Belanger clashed with Weaver over playing down the stretch and finished with a .165 batting average in 64 games. But his work during the strike that summer as a player negotiator helped bring the conflict to an end – and laid the groundwork for his post-playing days.

After 17 seasons with the Orioles, Belanger became a free agent following the 1981 campaign and signed with the Dodgers. But despite a salary that was reported to be in excess of $200,000, Belanger did little more than enter games as a late-inning defensive replacement in 1982. He came to the plate just 57 times in 54 games, hitting .240.

Belanger retired following the 1982 season, turning down a reported $200,000 offer from the Yankees to join Personal Management Associates, a Baltimore firm that represented more than four dozen athletes. But Belanger did return to the field in March as a Spring Training instructor with the Orioles, helping a young group of Baltimore infielders that included Cal Ripken Jr.

“Certainly, I would like to have more money,” Belanger told the Miami Herald in the spring of 1983. “But my inner self is what matters. I would take no amount of money to go out and possibly make a fool of myself or ever risk embarrassment for my family.

“A lot of people say: ‘I’m going to play until they tear the uniform off me.’ Not me.”

Belanger’s work helped the Orioles win the 1983 World Series – with Ripken earning the American League Most Valuable Player Award at shortstop. That summer, Belanger was inducted into the Orioles Hall of Fame.

“It’s like he was never away,” former Orioles teammate Mike Flanagan told the Miami Herald.

But Belanger’s future was not as a coach. He worked for years with the Major League Baseball Players Association, becoming a respected voice as the union expanded rights and benefits for the players.

A longtime smoker, Belanger was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1997 and passed away on Oct. 6, 1998, at the age of 54. He finished his 18-year big league career with a .228 batting average and 1,316 hits, but that only tells a portion of the story.

Belanger’s defense was so good that he remains the only non-pitcher in big league history with a career batting average of less than .240 and a total WAR of 40-or-better.

“I would have to say,” former Orioles teammate Rick Dempsey told the Miami Herald, “(Belanger) was the most important person who helped the Orioles in all the pennant drives. He held that infield together.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

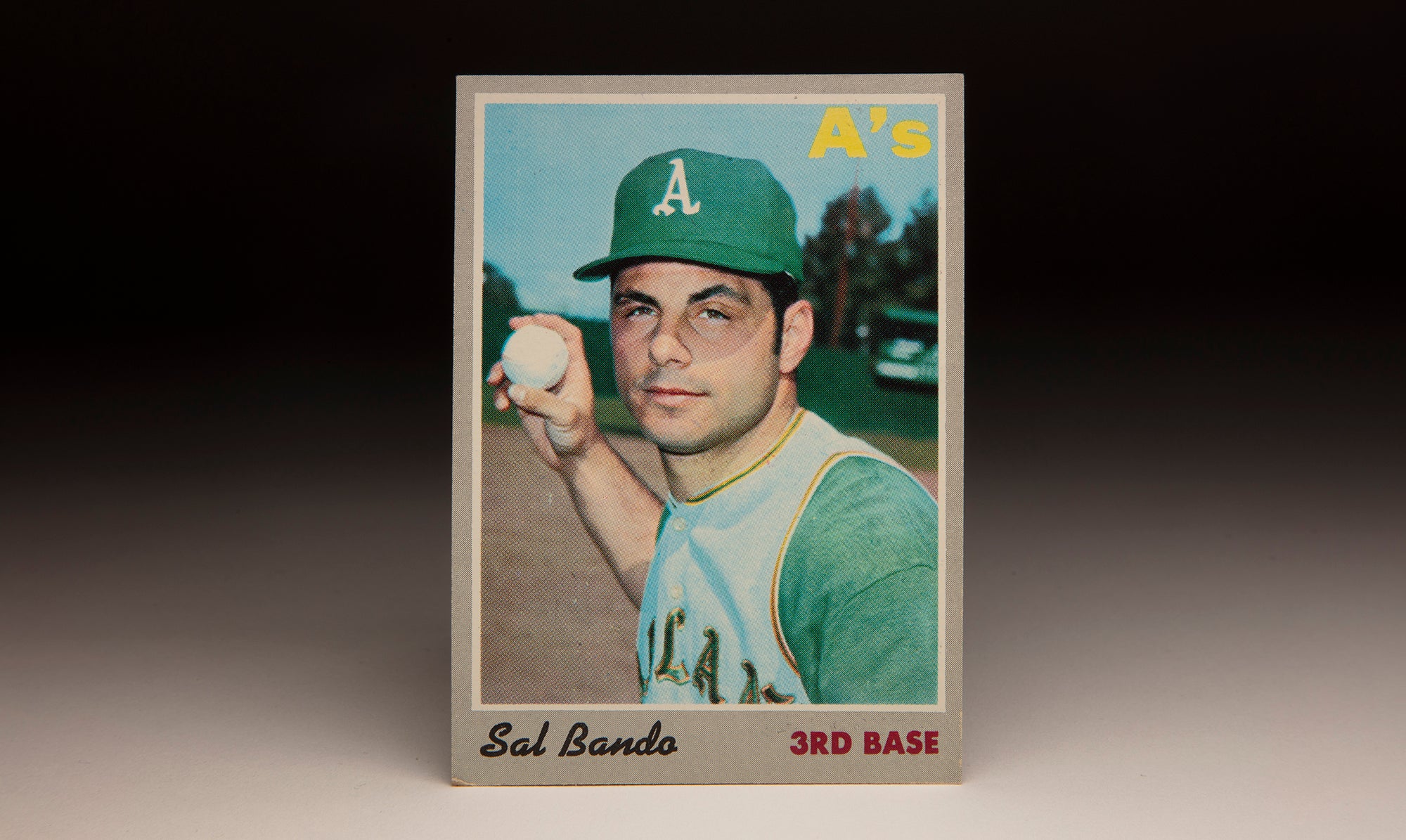

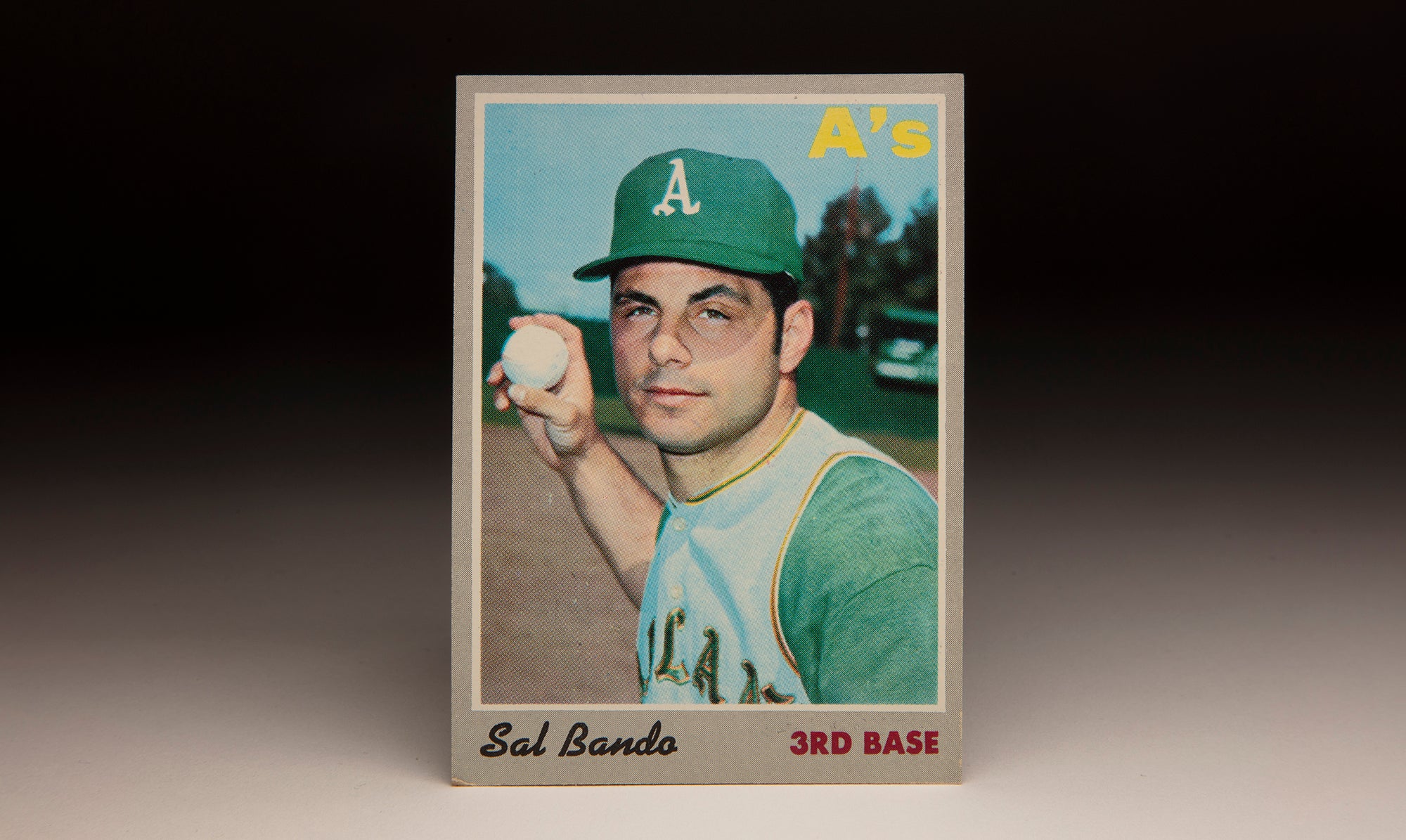

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Sal Bando

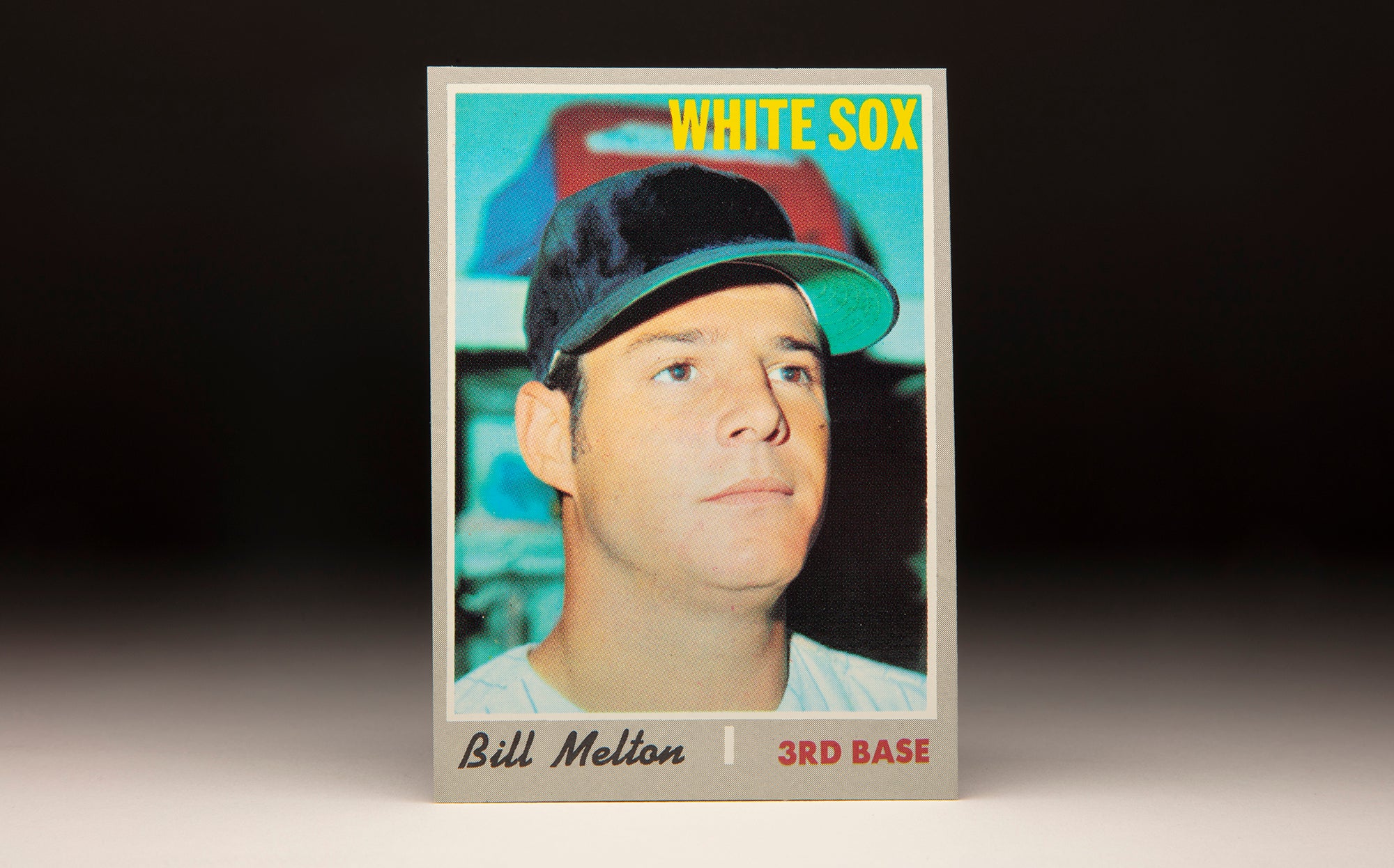

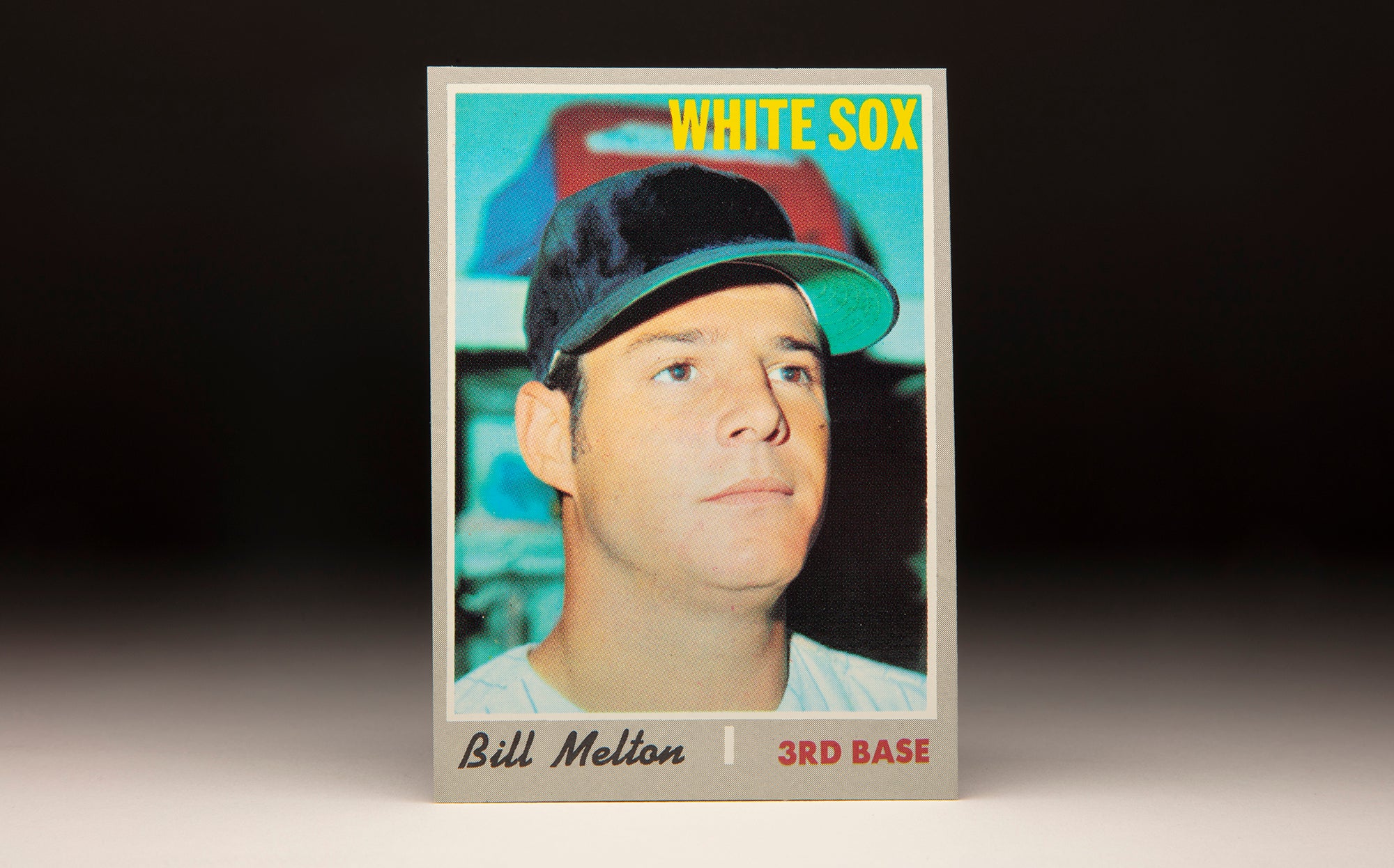

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Bill Melton

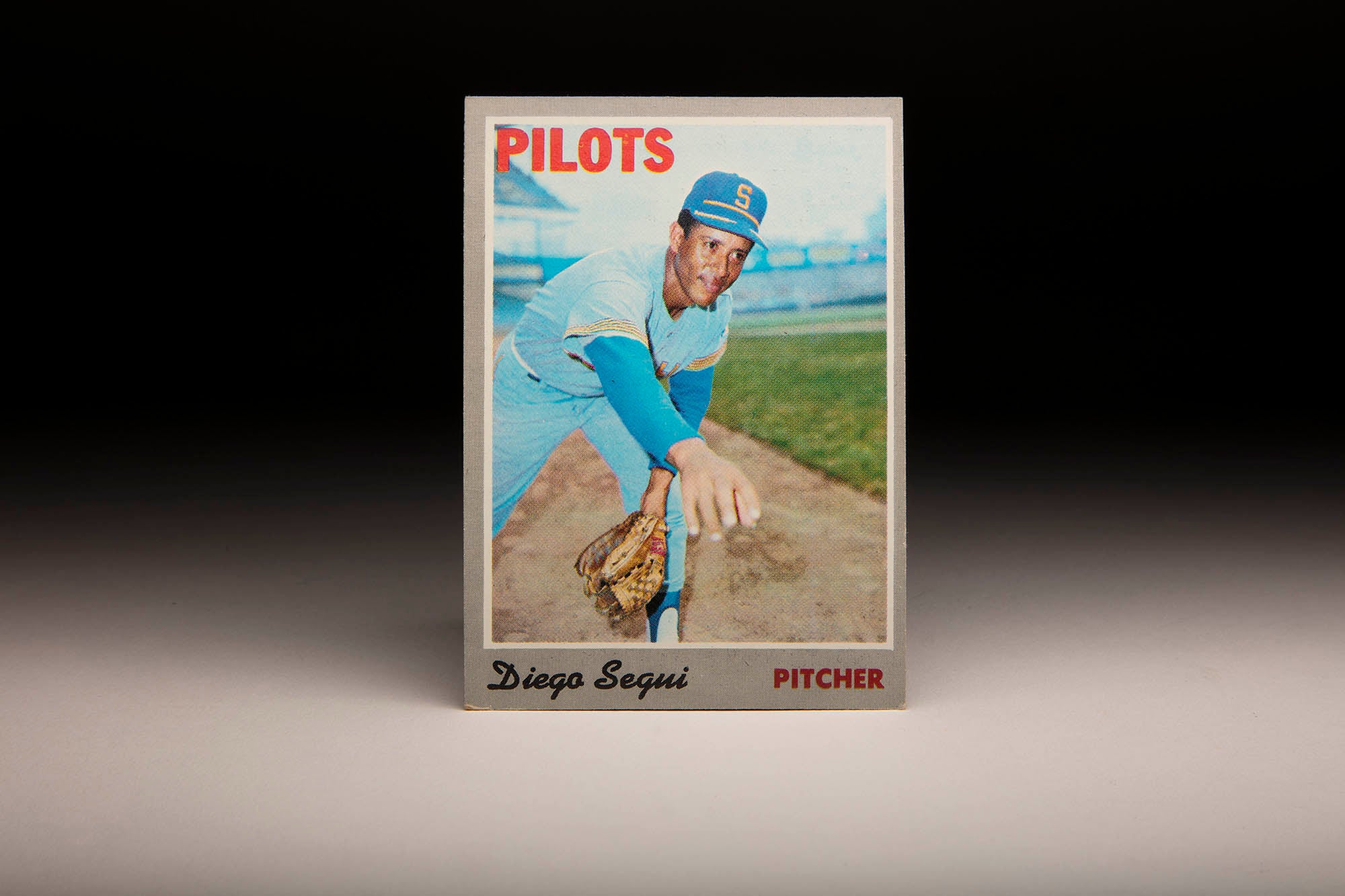

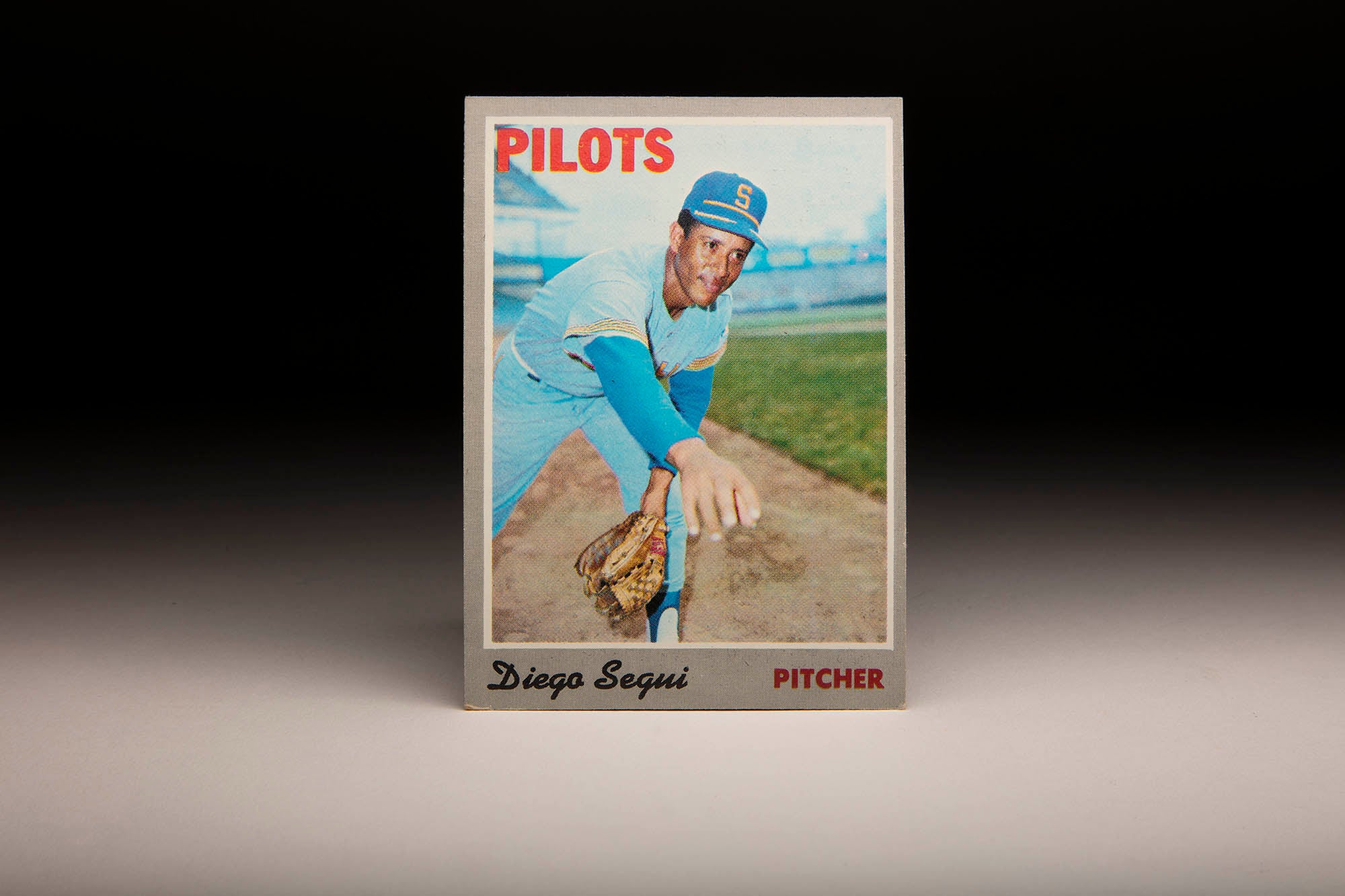

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Diego Seguí

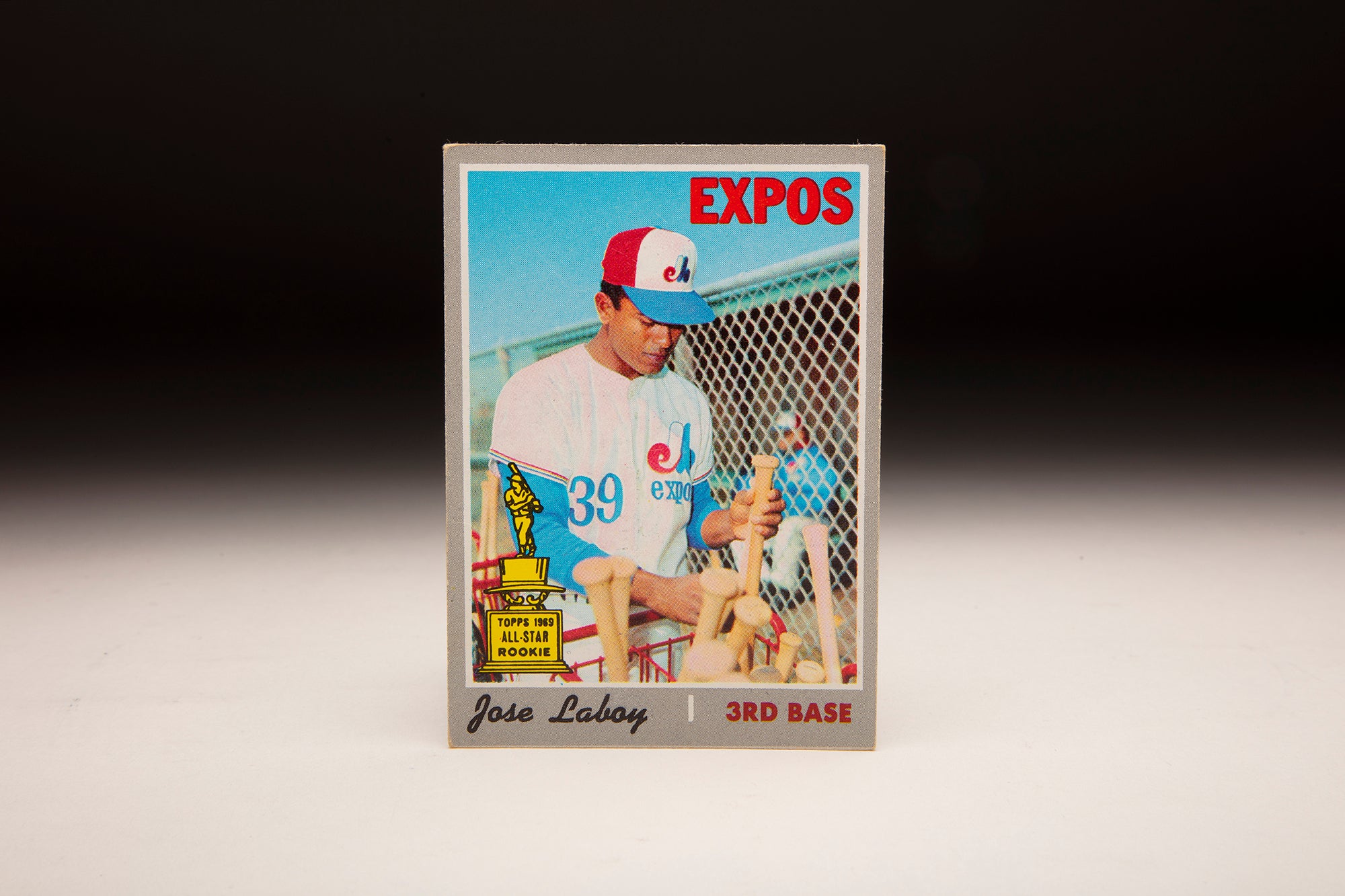

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Jose ‘Coco’ Laboy

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Sal Bando

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Bill Melton

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Diego Seguí