- Home

- Our Stories

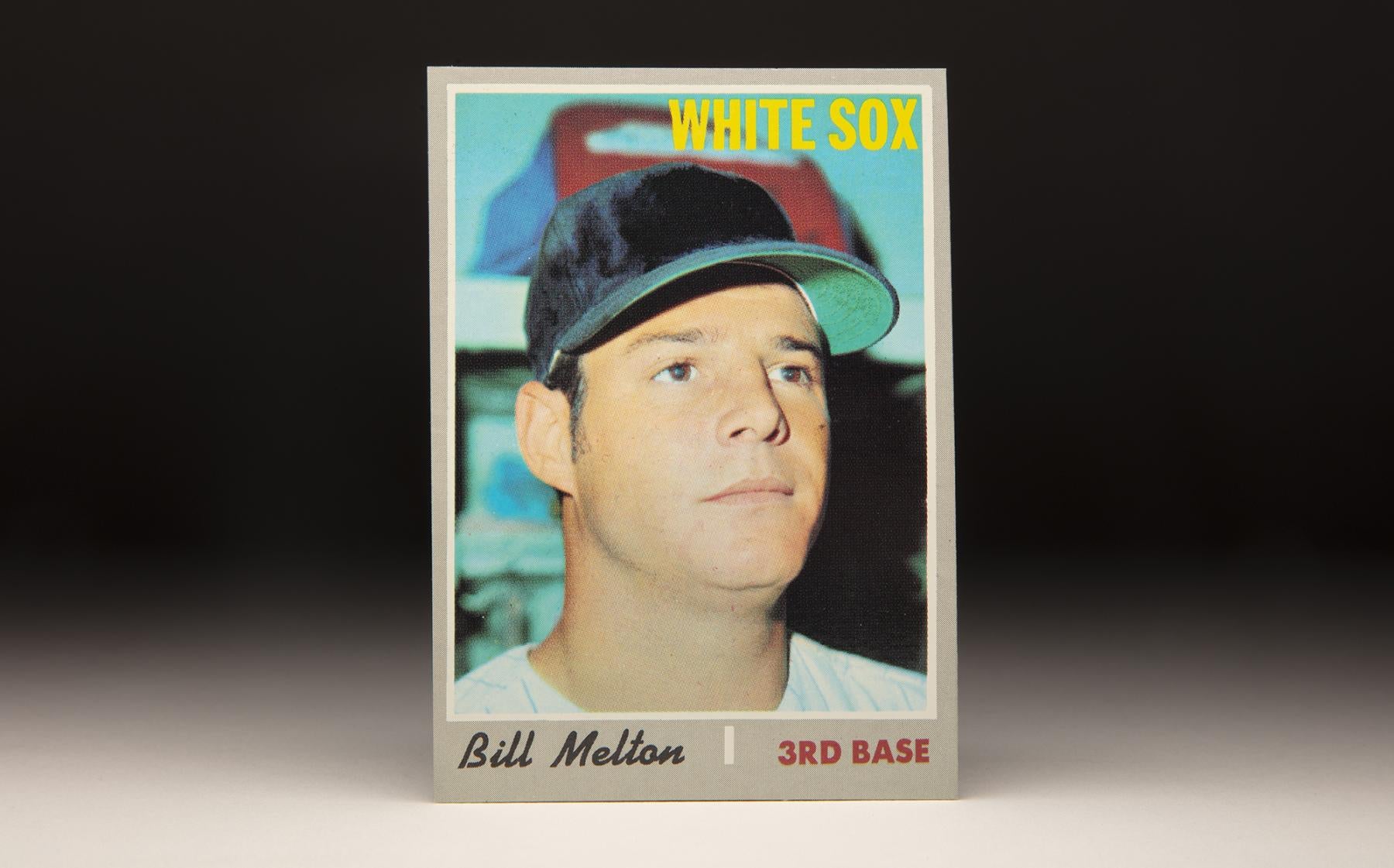

- #CardCorner: 1970 Topps Bill Melton

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Bill Melton

Bill Melton grew up in sun-splashed Southern California, which has produced its share of amateur baseball talent.

But Melton never played high school baseball, concentrating instead on football and basketball.

Within five years of his high school graduation, however, Melton found himself in the big leagues. And he would soon be recognized as one of the leading power hitters in baseball.

White Sox Gear

Represent the all-time greats and know your purchase plays a part in preserving baseball history.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Born July 7, 1945, in Gulfport, Miss., Melton moved with his family – his father was in the Navy – to Southern California while still an infant. After graduation from Duarte High School, he enrolled at Citrus College in Glendora, Calif., and decided to try his hand at baseball. He had not played on the diamond since Little League.

“Not playing (youth baseball) has hampered me,” Melton told the Progress Bulletin in Pomona, Calif., in 1971 when he became the first White Sox player in history to lead the AL in home runs. “I feel I could have made the major leagues sooner with more experience. Even in the minors, I felt I didn’t know anything about the game. It made it a lot tougher.”

At Citrus College, Melton hit .300 with nine home runs in his only season before signing as an amateur free agent with the White Sox in 1964.

“I was tired of working (after high school) and Galen Bowman (Citrus College’s baseball coach) gave me the chance even though he didn’t know where to play me,” Melton told the Progress Bulletin. “My big hope was to earn a college scholarship. San Diego State was interested in me.”

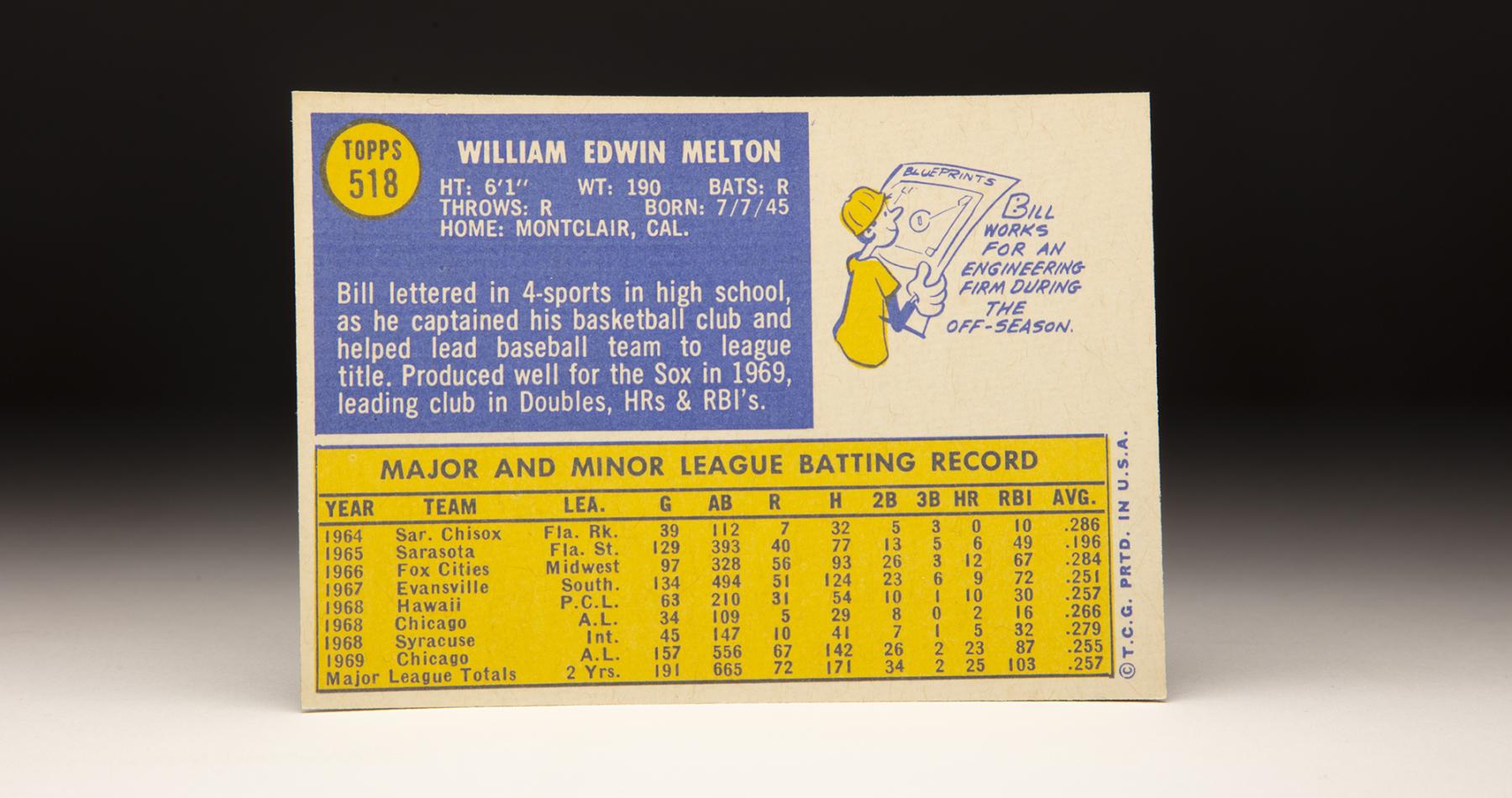

But after Melton impressed White Sox’s scouts with some long home runs, he was on his way to Chicago. After some time in rookie ball in 1964, Melton spent the 1965 season with Sarasota of the Florida State League, hitting .196 with just six home runs in 129 games – mostly in the outfield. The White Sox sent him to the Florida Winter Instructional League after the season, and there – surrounded by other top prospects – Melton began to grasp the intricacies of the game.

He was promoted to Fox Cities of the Midwest League in 1966, where he hit .284 with 12 homers and 67 RBI in 97 games. Returning to the FWIL in the fall, Melton hit .331 to stamp himself as a top prospect.

In 1967, Melton began to work at third base. He spent that season with Double-A Evansville, hitting .251 with nine homers and 72 RBI. Then on May 4, 1968, Melton made his big league debut – starting at third base against the Yankees a day after the White Sox released Ken Boyer to make room on the roster.

He hit a sacrifice fly off Fred Talbot in his first at-bat and later singled in Chicago’s 4-1 win.

Melton spent the next two weeks as Chicago’s starting third baseman but hit only .204 with no homers and three RBI in 17 games before being sent back to Triple-A for more seasoning.

He finished the season with 15 homers and 62 RBI combined with Syracuse and Hawaii.

In 1969, the White Sox entered the season with Melton as their third baseman.

“We sent him to the Winter Instructional League to polish his defensive play,” said future Hall of Famer Al López, who began the 1969 season as Chicago’s manager and installed Melton as his everyday third baseman. “And he developed rapidly. I think he is ready.”

Melton was hitting .280 by the end of April, firmly establishing his grip on the job. He appeared in 157 games that season – 148 of which came at third base – hitting .255 with 23 homers and 87 RBI. Defensively, he committed 22 errors but had a respectable .952 fielding percentage and finished fourth among AL third basemen with 322 assists, just 48 behind Gold Glove Award winner Brooks Robinson.

“I’m still pretty green myself and have a lot to learn (at third base),” Melton told the Tampa Bay Times in the spring of 1969. “But if you’ve got Luis Aparicio playing next to you at shortstop, it makes life a lot easier. I mean, he makes you look good as a third baseman.”

Aparicio, on his way to the Hall of Fame but nearing the end of his career, teamed with Melton on the left side of Chicago’s infield in both 1969 and 1970 and won a Gold Glove Award in the latter year.

Melton continued to post strong power numbers in 1970, hitting 33 home runs to go with 96 RBI. The White Sox, however, lost a franchise-worst 106 games that season – leading to an overhaul that saw Aparicio traded to Boston following the season.

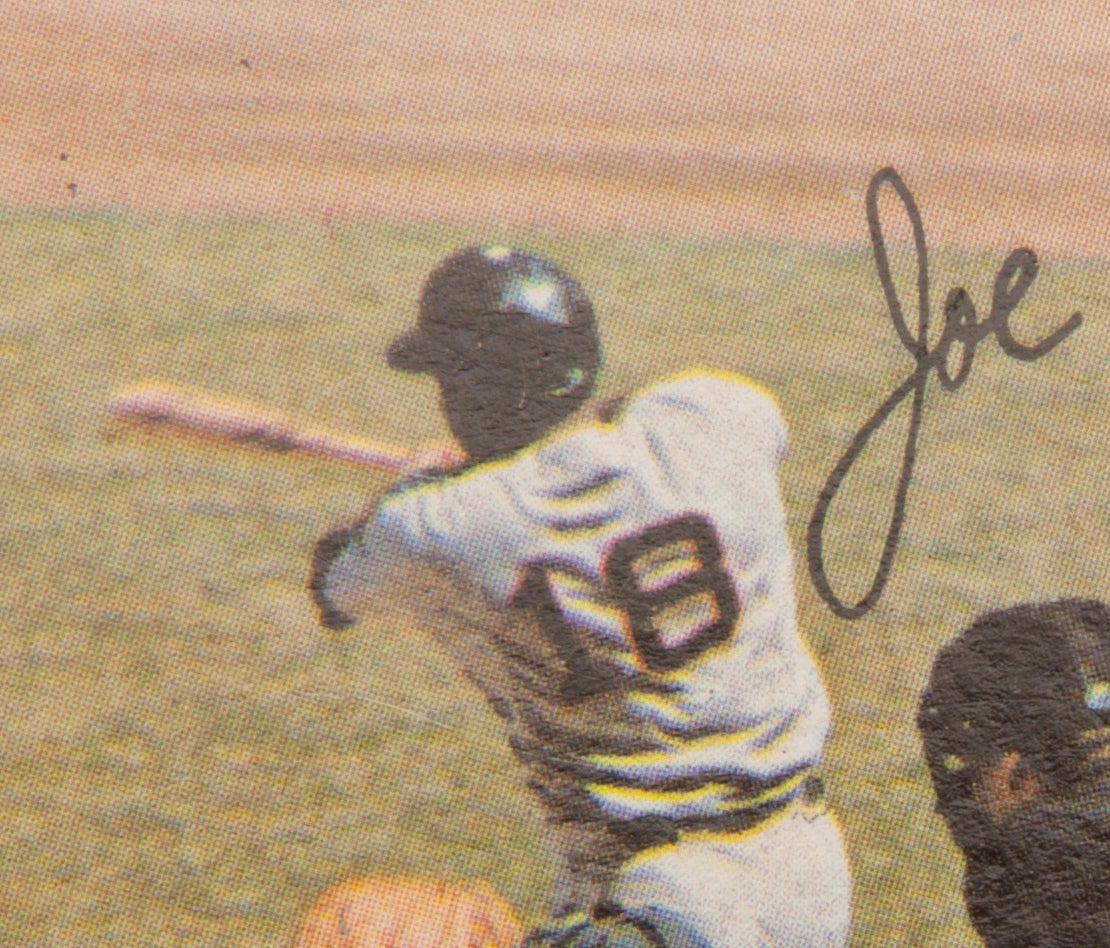

With new manager Chuck Tanner in charge in 1971, Melton had only six home runs through May but got red hot in June – totaling 12 homers and 26 RBI in 26 games. Going into Chicago’s final two games of the season, Melton had 30 homers, two behind Oakland’s Reggie Jackson and Detroit’s Norm Cash.

But Jackson and Cash both went homerless on Sept. 29, which was the last day of the regular season for both the Athletics and the Tigers. Meanwhile, Melton homered twice that day to create a three-way tie for the lead.

On the season’s final day, Sept. 30, Tanner batted Melton in the leadoff spot so he’d get the most plate appearances possible – and Melton homered in the third inning off Milwaukee’s Bill Parsons to claim the crown with 33 home runs.

It was the first time in 71 years of American League play that a White Sox player led the league in home runs.

“I didn’t set any goals when the season started,” Melton told the Progress Bulletin. “If I had, I don’t know what they would have been. But 33 home runs feels pretty good.”

Melton felt pretty good about his team situation as well.

“There weren’t many thrills in 1970 playing for a last place team,” Melton said. “Under (Chuck) Tanner, it’s been a big change.”

The White Sox finished at 79-83 and in third place in the AL West in 1971. Melton was named to the AL All-Star team and finished 13th in the AL Most Valuable Player voting.

But after appearing in 57 of the White Sox’s first 58 games in 1972, Melton was sidelined with a spinal issue that was causing leg discomfort. The herniated discs landed him on the disabled list and he did not appear in a game after June 23, finishing the season with a .245 batting average, seven homers and 30 RBI.

The White Sox, meanwhile, finished a surprising 87-67, five-and-a-half games behind the first-place Athletics in the AL West and with an incredible 31 more victories than they totaled just two years earlier.

“I’ve been in the major leagues for five years, and I’ve never been on a winner,” Melton told the Associated Press in August as he desperately tried to return to the field. “And now this…

“Every week I watch the Game of the Week on television and eat my heart out.”

Melton returned for the 1973 season after offseason back surgery and started strong, hitting .302 with 10 homers and 39 RBI through June 1. He finished the year with a career-best .277 batting average to go with 20 home runs, 29 doubles and 87 RBI – but the White Sox finished a disappointing 77-85.

“Melton’s as good an all-around third baseman as there is in the league,” Tanner told the Daily Herald of Chicago. “When you talk about fielding and hitting, Bill’s the best.

“He’s only interested in one thing: How many games we’ve won at the end, not the individual statistics.”

But on Dec. 11, 1973, the White Sox sent four players to the Cubs – Ken Frailing, Steve Stone, Steve Swisher and Jim Kremmel – in exchange for future Hall of Fame third baseman Ron Santo. Suddenly, Melton thought his job might be in jeopardy.

“I was given a tag as a bad third baseman,” Melton told United Press International prior to Spring Training. “The fact is I was never a third baseman until I got to the big leagues.

“I lived through two years of (the press) telling me how bad I was. I can live through this, too.”

Melton needn't have worried. He played 123 games at third base in 1974, hitting 21 homers and driving in 63 runs after a slow start. Santo, in the final year of his big league career, appeared in more games at DH (47) and second base (39) than third (28) that year and hit .221.

By the spring of 1975, Melton had third base all to himself and installed as the White Sox’s cleanup hitter. He played in 149 games that season, but his power and bat speed appeared to be eroding, as he hit .240 with 15 homers and 70 RBI.

Then on Dec. 11, 1975, new White Sox owner Bill Veeck pulled off a major trade at the Winter Meetings, sending Melton and pitcher Steve Dunning to the Angels for Morris Nettles and Jim Spencer. That same day, the Angels acquired Bobby Bonds from the Yankees in exchange for Ed Figueroa and Mickey Rivers – leading many to believe that the retooled Angels were ready to compete in the AL West.

“We traded 92 stolen bases and picked up 47 home runs,” Angels general manager Harry Dalton told the Associated Press.

But the Angels’ plans went awry when Bonds broke his hand at the end of Spring Training and missed the team’s first nine games. Melton moved into the team’s cleanup spot, but manager Dick Williams kept Dave Chalk at third base and used Melton as the DH. Melton never got untracked, clashed with Williams on a team bus in late July (Williams was fired by the team soon after) and finished the season with a .208 average, six homers and 42 RBI in 118 games.

In 15 games against Chicago, however, Melton – who had feuded with White Sox broadcaster Harry Caray – hit .260 with 11 RBI, his most against any team that season.

“I went through that all last year,” Melton told the Independent of Long Beach, Calif., of his troubles with Caray and booing White Sox fans. “I’ve mellowed out. I’d like to beat every team if I could.”

On Dec. 3, 1976, the Angels sent Melton to the Indians in exchange for a player to be named later – which turned out to be Stan Perzanowski.

Melton battled with Boog Powell for the Indians first base job in Spring Training of 1977, and Melton – who scorched Cactus League pitching that spring – secured a roster spot when Powell was released on March 30.

“My mental attitude is good this spring,” Melton told the Progress Bulletin. “You’ve got to start off thinking nothing but positive things. You’re wasting your time for six months if you come out here and think negative.”

But injuries and ineffectiveness hampered Melton’s 1977 season, and he appeared in just 50 games while hitting .241 with no home runs. He became a free agent after the season and retired soon after.

Melton later worked on Cubs and White Sox television broadcasts before passing away on Dec. 5, 2024, at the age of 79. Though his tenure in Chicago was at times rocky, he retired as the White Sox’s all-time leading home run hitter with 154 – a title he held until Harold Baines passed him in 1987.

“I have good memories of my eight years (in Chicago), except for that last one,” Melton told the Journal Times of Racine, Wisc., in 1977. “I have a lot of good memories, like 1971. In the eight years I was there, that’s something we had always strived for: To generate some excitement.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

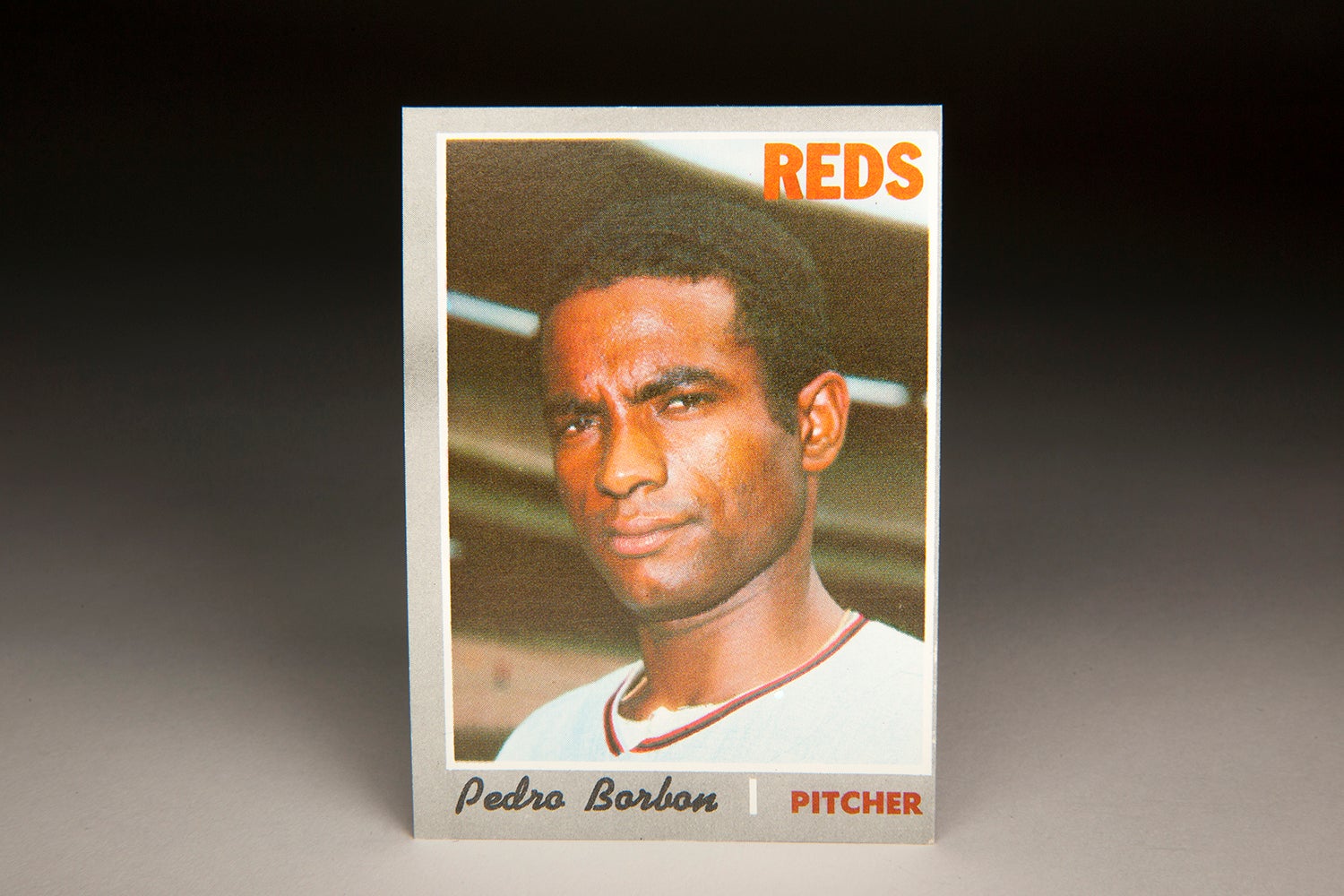

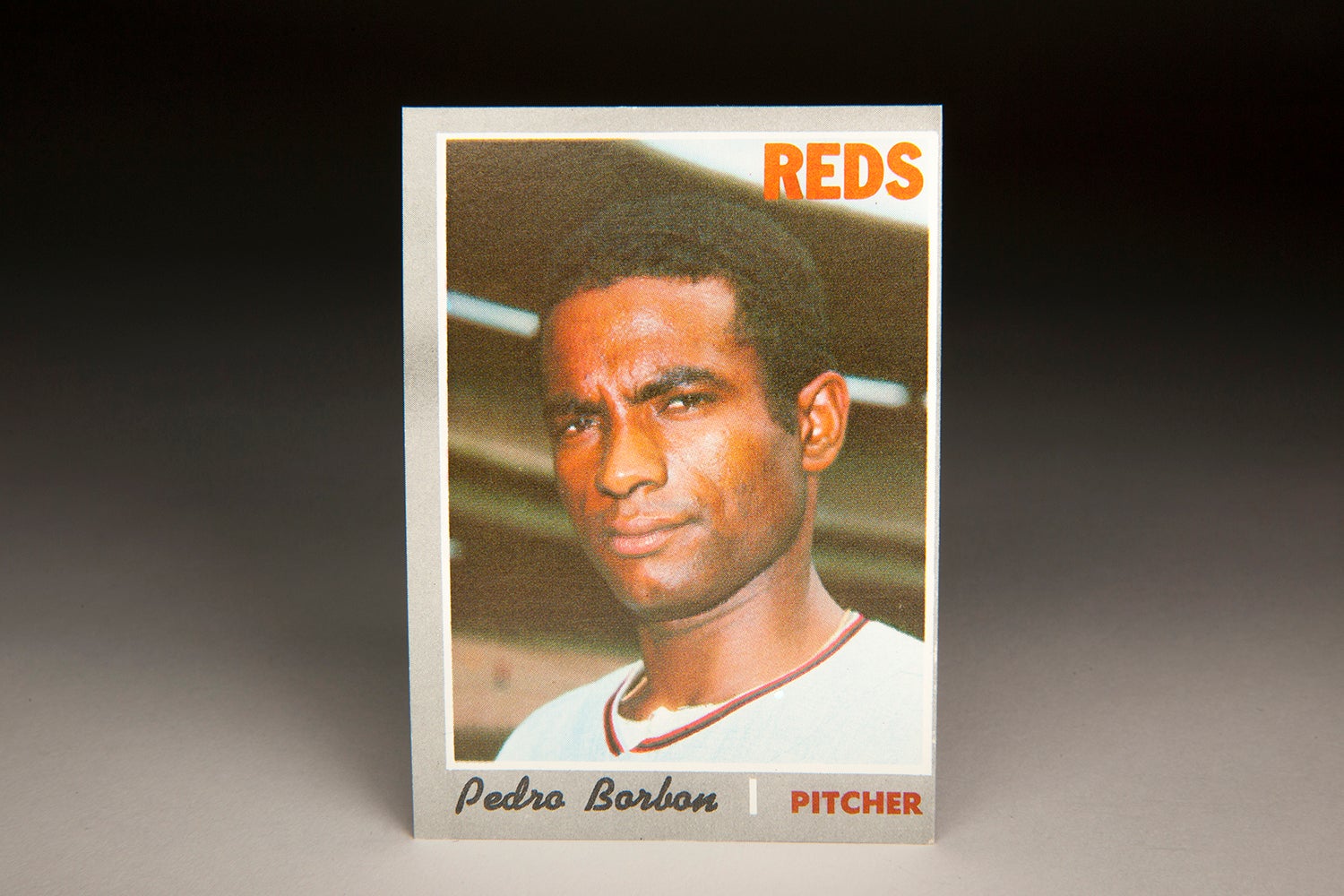

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Pedro Borbón

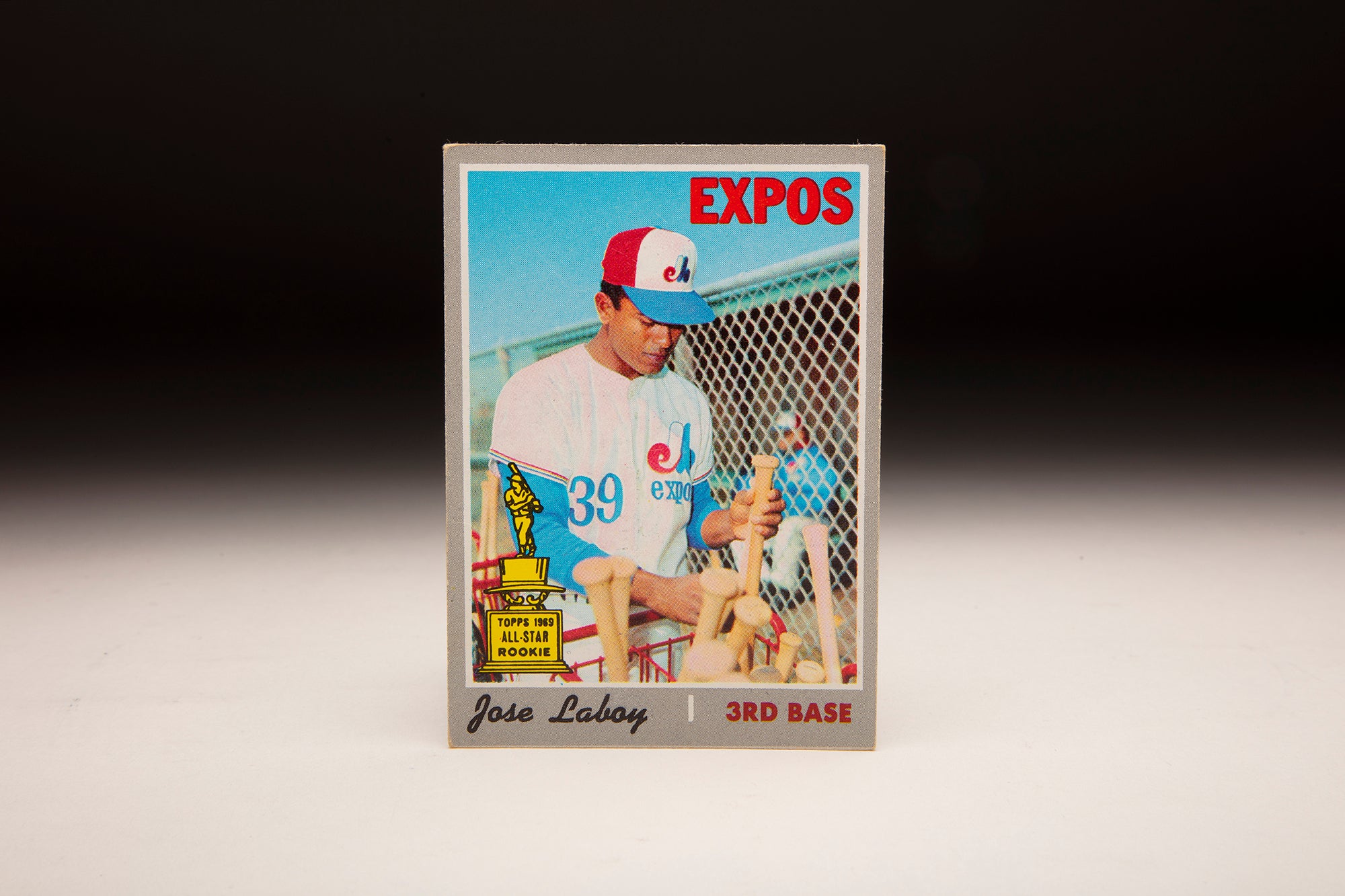

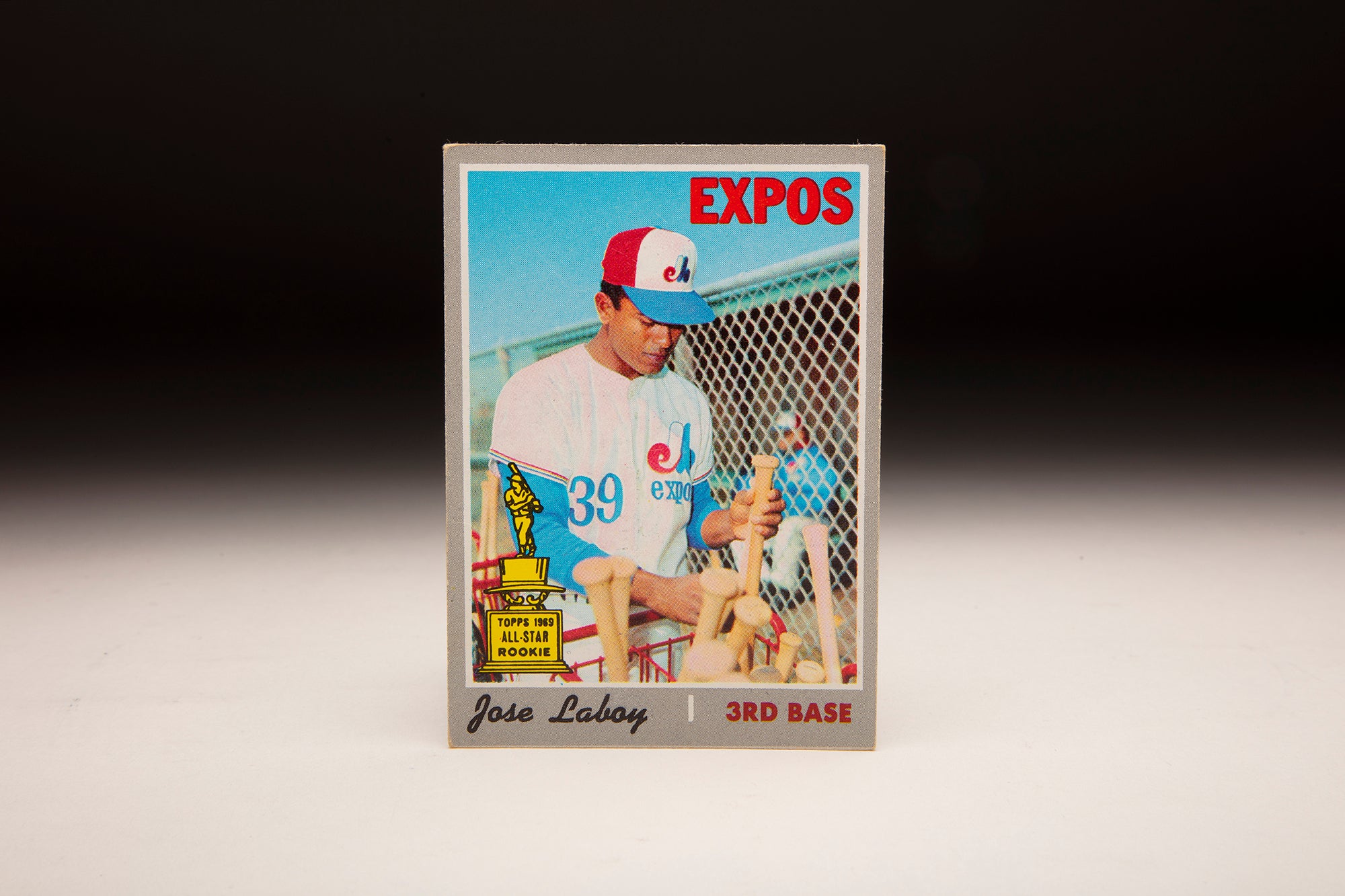

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Jose ‘Coco’ Laboy

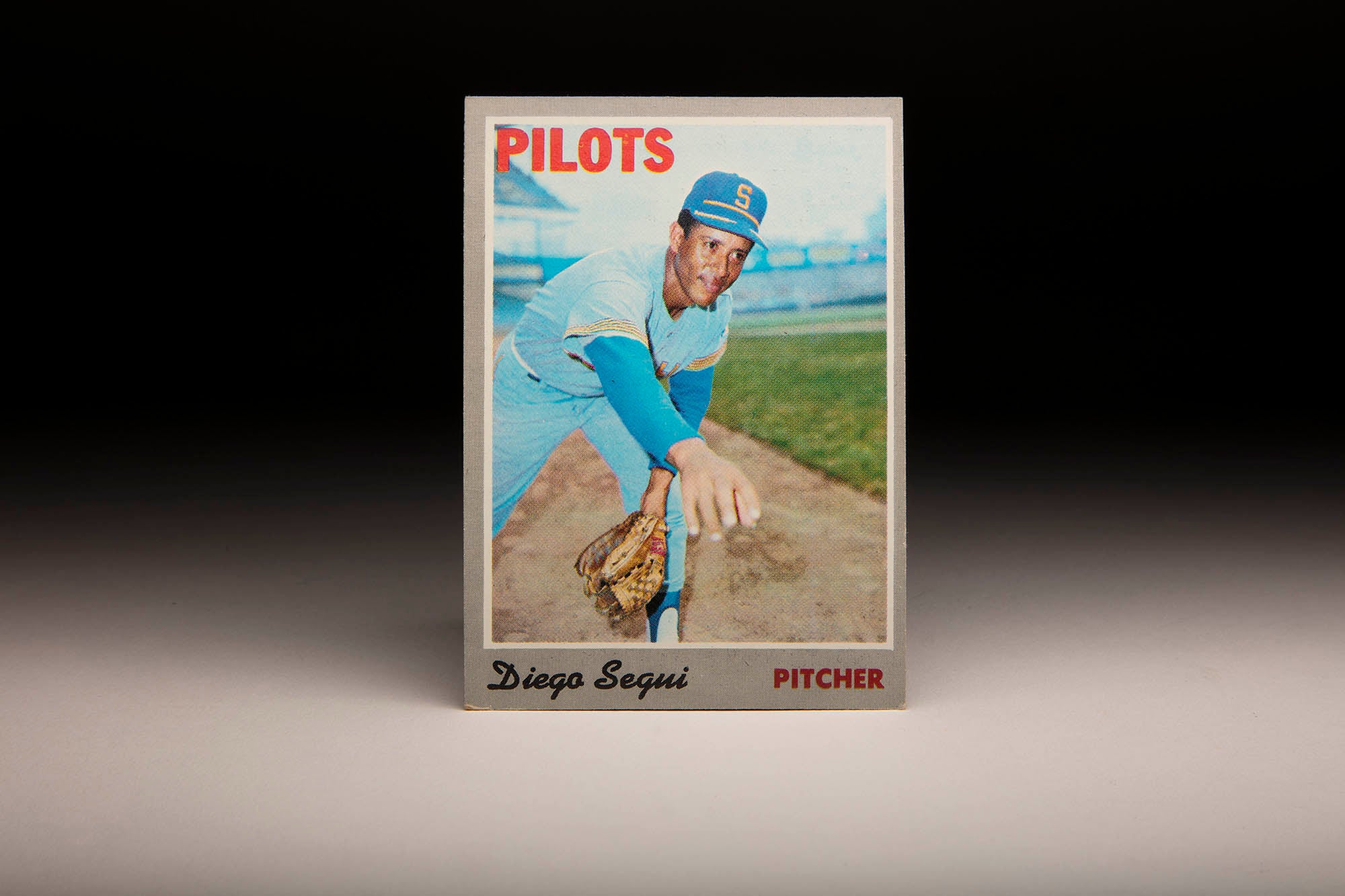

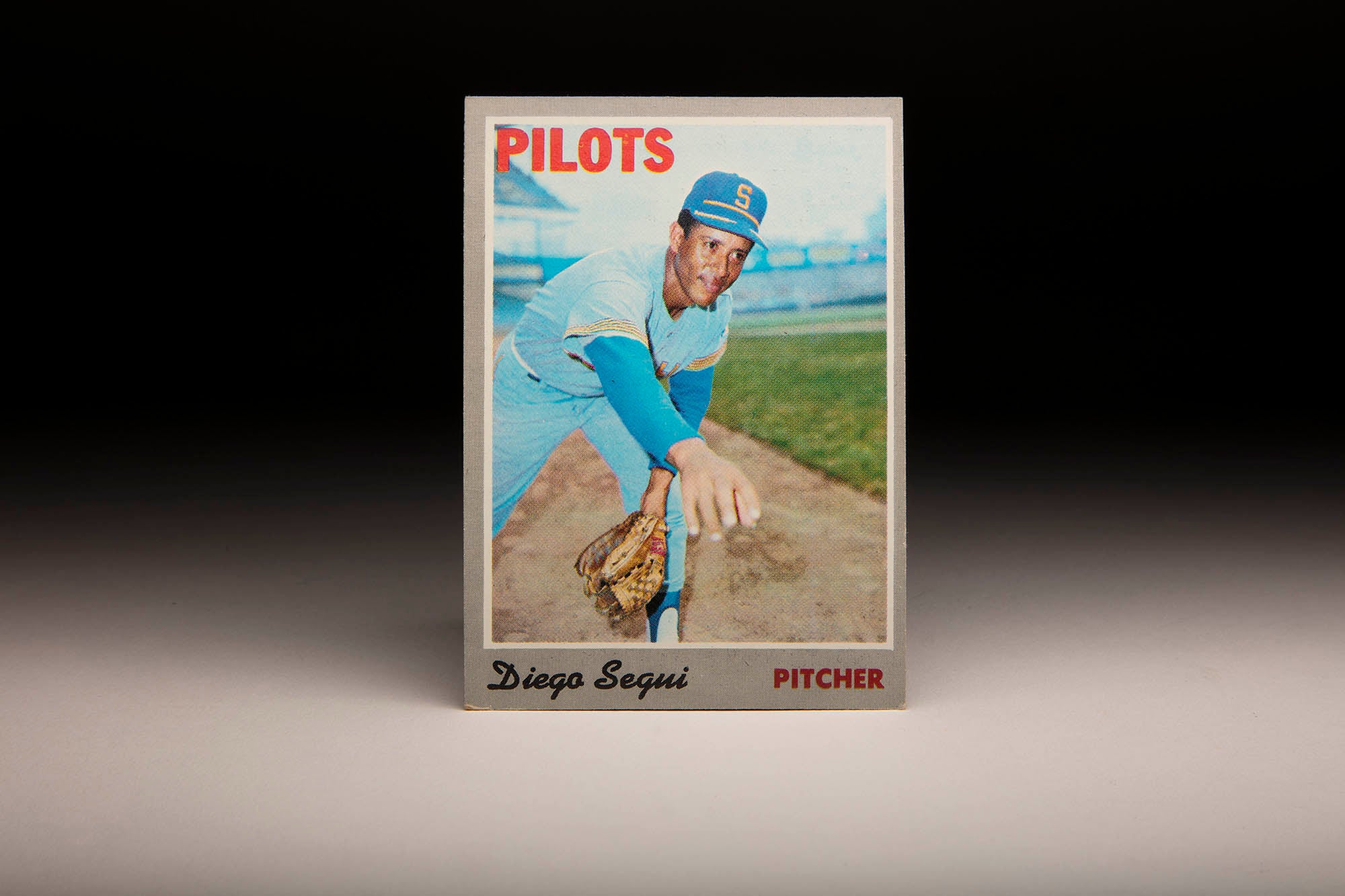

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Diego Seguí

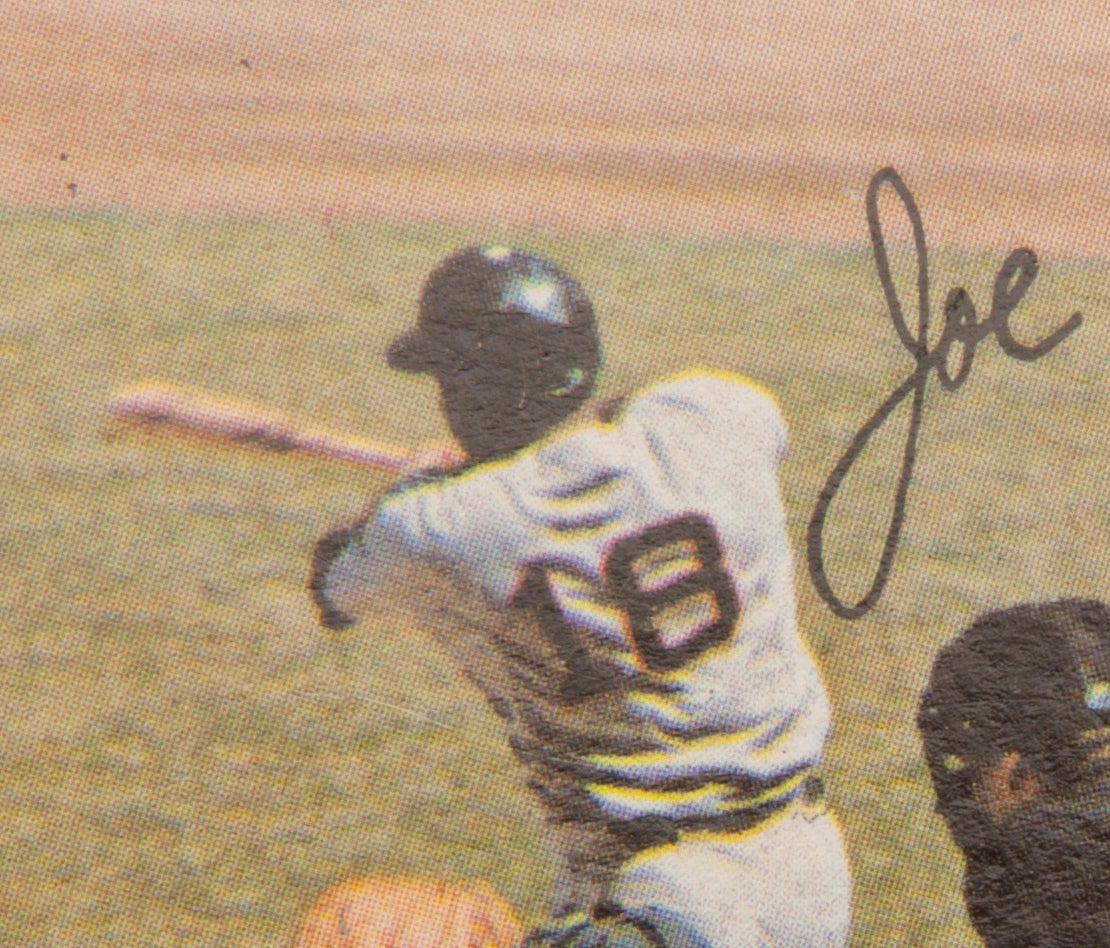

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Joe Morgan

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Pedro Borbón

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Jose ‘Coco’ Laboy

#CardCorner: 1970 Topps Diego Seguí