- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1969 Topps Leon Wagner

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Leon Wagner

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

In 1969, Leon Wagner made his final (not to mention most unusual) appearance on a Topps card.

The card is notable because he is clearly wearing the colors of the Cincinnati Reds, a team for which he never played, not even for a single game. That is somewhat easily explained, but what is much harder to figure out is this: How exactly did Topps find the time to photograph Wagner in a Reds uniform?

Let’s try to explain all of this. Wagner spent the 1968 season split between the Cleveland Indians and the Chicago White Sox. On June 13, the Indians traded him to the White Sox for infielder Russ Snyder. It wasn’t until after the season, Dec. 5, to be more exact, that the White Sox sold Wagner to the Reds. Given that Topps usually took photographs of players during the preceding season, and sometimes earlier seasons, it’s somewhat mystifying that the company managed to obtain a legitimate picture of Wagner in his new Reds uniform – and didn’t have to rely on airbrushing or cover-up.

There is another possibility. Occasionally, Topps would photograph a player during the current Spring Training, and then include that card in one of its later series. But the Wagner card is numbered 187 in the 1969 Topps set, which would have made it part of Topps’ second series, and not one of the later series of cards. As a result, it seems unlikely that Topps would have had time to send a photographer to Spring Training early in 1969 and then rush an updated Wagner card into production, in time to be included in series No. 2.

Furthermore, the background of the Wagner card offers us an additional clue. The upper deck and the accompanying light stanchion do not look the typical backdrop of a Spring Training ballpark. No, that looks to me to be a major league park. Since Wagner is wearing the home uniform of the Reds, I would assume that it is Cincinnati’s Crosley Field.

But what exactly would Wagner have been doing at Crosley Field, when he never actually played a game for the Reds? Cincinnati acquired him in early December and then brought him to Spring Training in 1969, only to return him to the White Sox on April 5, just before Opening Day. Wagner did not make the Reds’ Opening Day roster and never appeared in a regulation game for the Reds, so how is it he came to be photographed at Crosley Field, if that is actually Crosley Field to begin with?

My guess – and it’s strictly a guess – is that after acquiring Wagner from the White Sox in December, the Reds brought him to Cincinnati for some kind of photo opportunity during the winter. Perhaps it was a mild winter day in Cincinnati, one lacking in snow and cold, giving the Reds a chance to photograph Wagner outdoors. Topps then could have acquired the photo from the Reds. I have no other explanation for how Topps managed to finagle a photo of Wagner wearing his new Reds uniform.

Quite obviously, Wagner’s 1969 card brings with it plenty of intrigue, most of which is rather trivial in context. That’s because the card also brings with it a large degree of sadness, based on what happened to Wagner after his playing days, and how his life ended under such forlorn circumstances.

Many years earlier, Wagner’s career seemed to begin in nearly storybook fashion. He was playing sandlot ball in Michigan, for a team called the Inkster Panthers, when he caught the eye of New York Giants scout Ray Lucas. Wagner signed with the Giants prior to the 1954 season and soon received an assignment to Danville of the Class D Mississippi-Ohio Valley League.

Wagner showed little trouble in making the transition to pro ball. He hit .332 with 24 home runs. It was only on defense that Wagner showed any vulnerability. He committed 14 errors in the outfield, the highest total for any outfielder in the MOV League.

With his ferocious left-handed swing, Wagner continued his assault on minor league pitching over the next two seasons. In 1955, he batted .313 and led the Class C Northern League with 29 home runs. The following summer, he moved on to the Carolina League, where he posted numbers that appeared almost Ruthian: 51 home runs and 166 RBI.

While Wagner dominated the league, racism made his life difficult. During one road game, he was verbally warned by a rifle-toting fan not to catch the next ball hit his way. Wagner took the threat seriously. Out of fear for his life, he intentionally dropped the next ball hit in his direction.

Wagner encountered a different turn in the road after the ’56 season. Drafted into the U.S. Army in the era following the Korean War, Wagner would serve the next 14 months at Fort Carson, Colo., where he spent most of his time driving a military jeep. As a result, Wagner missed all of the 1957 minor league season, curtailing his development.

Wagner returned to the Giants’ organization in 1958. By now, the Giants had moved from New York to San Francisco, and had placed their Triple-A affiliate at Phoenix. Convinced that Wagner was ready to play at the highest level of the minor leagues, the Giants assigned him to Phoenix to start the ’58 season. Over his first 65 games, Wagner batted .318 with 17 home runs, numbers that become more remarkable given his year-long absence from the game. It was obvious to all within the organization that he was ready for his first major league audition.

The Giants recalled Wagner in June; on the 22nd of the month, he made his debut. Quickly becoming the Giants’ regular left fielder, he batted .317 with 17 home runs in 74 games, or roughly the equivalent of a half-season of play.

If Wagner had played the entire season in San Francisco, he might have won the Rookie of the Year Award. But with only a few months of service time, he received no consideration for the honor. Still, he gave the Giants every indication that he would be playing alongside Willie Mays in a power-packed outfield for a long time to come.

Giants manager Bill Rigney, however, harbored reservations about Wagner’s defensive play. Wagner’s frequent errors led Rigney to make a change in left field, opting to give Jackie Brandt most of the playing time in 1959. Given infrequent opportunities to play, Wagner’s hitting suffered; he batted only .225 with scant power.

The Giants gave up on Wagner quickly. After the season, they traded him to the St. Louis Cardinals as part of a package for veteran second baseman Don Blasingame. The trade left Wagner feeling bitter; he criticized Rigney and coach Salty Parker for focusing too much on his defensive mistakes and exaggerating his supposed inability to handle basic outfield chores.

With Stan Musial, Curt Flood and Joe Cunningham stationed in the Cardinals’ outfield, there was little opportunity for Wagner to play in St. Louis. Settling for a role as a backup outfielder and pinch-hitter in 1960, Wagner appeared in 39 games and totaled only four home runs. By mid-June, the Cardinals felt he would be better off playing every day at Triple-A Rochester. Wagner hit with power in his return to the minor leagues, but his batting average fell off to .265, the worst mark of his minor league career.

The 1961 season brought two new teams to the American League: The expansion Washington Senators and the Los Angeles Angels. Neither team selected Wagner in the expansion draft, but he would soon find himself with one of the new teams. In April of 1961, the Angels acquired Wagner in a trade with the Cardinals. As a new franchise, the Angels desperately needed offensive talent, a skill that Wagner was more than capable of providing.

The trade reunited Wagner with Bill Rigney, his former manager in San Francisco. Now the field boss of the expansion Angels, Rigney took a different tact with Wagner. He made Wagner his regular left fielder. Over the balance of the season, Wagner hit .280 with 28 home runs and a .517 slugging percentage. He also showed off a strong throwing arm, recording a total of 10 assists.

Using that season as a springboard, Wagner became a near-star in Southern California. In 1962, Wagner roared in April, hitting nine home runs over his first 18 games. By season’s end, he had hit 30 home runs and compiled a slugging percentage of an even .500. Wagner placed fourth in the American League MVP voting that fall, finishing behind only Mickey Mantle, Bobby Richardson and Harmon Killebrew.

Wagner’s season included selections to both All-Star Games, including an MVP Award for his performance in the second game. That MVP effort included an excellent running catch, which prompted Wagner to give a group of reporters a friendly dose of his wisdom after the game. “A man don’t have to be a bad fielder all his life. It isn’t that hard to catch baseballs.”

Wagner’s remarks represented a reaction to the growing criticism over his struggles in left field. His defensive foibles became the stuff of legend in Southern California. On one occasion, he tried to run down a ball that had settled under a bullpen bench. Wagner reached under the bench, grabbed what he thought was the ball, and then fired it toward the infield. There was just one problem: It wasn’t the ball; it was a paper cup filled with beer.

Not only had Wagner become a productive player with the Angels, but he also became popular with the local media, which enjoyed his outgoing nature and ever-present sense of humor. Fans enjoyed watching Wagner during his at-bats, as he went through a series of gesticulations in the batter’s box. Given his unusual body movements, the press dubbed him “Daddy Wags.”

Off the field, Wagner found some success when he became part-owner of a clothing store. He promoted the store with a tag line that only Wagner could create, “Get your rags from Daddy Wags.”

After his breakout of 1962, Wagner couldn’t quite sustain such a performance in 1963, but he still batted .291, with 26 home runs and an OPS of .809. With another fine season under his belt, along with another All-Star Game selection, Wagner seemed like he would remain an Angel for life. Then came a shocking development in December. The Angels surprised the media and their fan base by trading Wagner to the Cleveland Indians for pitcher Barry Latman and aging slugger Joe Adcock.

On the surface, the trade left many puzzled. After all, Wagner had become the first prominent slugger in the history of the young franchise. Some Los Angeles writers speculated that the Angels were upset with Wagner because he owed them money. The Angels had loaned Wagner cash to help out his failing clothing store, but the store went under anyway, leaving Wagner unable to repay the loan.

Another theory involved Wagner’s blunt assessment of general manager Fred Haney, whom he had once called “a sort of Khrushchev,” likening him to the Communist leader.

Whatever the actual reason for the trade, it certainly helped Cleveland. While Wagner’s batting average fell to .253, his power remained top notch, with 31 home runs. He also stole a career-high 14 bases. Wagner received some support in the MVP race, finishing 17th in the balloting.

Over the next two seasons, Wagner continued to put up big power numbers. He showed toughness, too. A 1966 collision with teammate Larry Brown, which resulted in a concussion and a broken nose, kept him on the sidelines for a handful of games. And just as he had in California, Wagner became a quotable favorite among the Cleveland media. He enjoyed making bold predictions, like one about breaking the single-season home run record. “If Roger Maris hit 61,” Wagner told Cleveland writer Hal Lebovitz, “I can hit 70.”

With his constant smile and his upbeat, positive attitude, Wagner earned the nickname “The Good Humor Man.” Fans in Cleveland loved his willingness to interact, particularly the way that he signed autographs with regularity at Municipal Stadium. Given his personality, Wagner became highly sought after by groups and businesses in need of a public speaker.

After three standout seasons in Cleveland, Wagner started to show cracks in his game in 1967. His power diminishing, he fell into a platoon role with Rocky Colavito. He finished the year with only 15 home runs, his worst output since his final season in St. Louis.

Wagner reported to Spring Training in 1968, hopeful of regaining his everyday job in the Indians’ outfield. It didn’t happen. Starting the season in a terrible slump, Wagner saw his batting average fall to .184. In mid-June, the Indians gave up on the 34-year-old slugger, dispatching him to the White Sox for Snyder. With Chicago, Wagner hit for average (.284) but managed only one home run in 162 at-bats.

After all of the roster machinations of the 1968/69 offseason, Wagner found himself back with the White Sox toward the end of Spring Training. In reality, the White Sox really didn’t want him. So on April 5, they gave him his release. In May, Wagner found work with his original team, the Giants, who offered him a minor league contract. After a stint at Triple-A, Wagner made his return to San Francisco in September. He showed some life by picking up four hits in 12 at-bats, but the Giants didn’t see enough in Wagner. In early October, they released Daddy Wags, who then played all of 1970 in the minor leagues.

In 1971, Wagner attempted to prolong his career as a player/coach with the Hawaii Islanders, a team in the Pacific Coast League that had become a haven for ex-major leaguers like Clete Boyer and George Brunet. But Wagner received only sporadic playing time, accumulating 143 at-bats over 75 games. At season’s end, he called it quits for good.

In light of his outgoing personality, Wagner might have seemed like a candidate to do well in his post-playing career. But his clothing store had long since gone under, forcing him to turn to other lines of, including a stint as a car salesman and some time doing public relations for a racetrack in the Los Angeles area.

What few connections Wagner had he used to procure work in Hollywood, leading to a role in the 1974 John Cassavetes film, A Women Under the Influence. In 1976, he appeared in a baseball-themed move, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars, which portrayed life in the Negro Leagues. The film, which starred Billy Dee Williams and James Earl Jones, proved entertaining, but drew criticism for being less-than-accurate in its portrayal of life in the Negro Leagues. It turned out to be Wagner’s final appearance in a Hollywood production. His days as an actor simply petered out.

To make matters worse, Wagner became severely addicted to drugs, which cost him most of his money and left him in severe debt. Penniless and without a home, Wagner ended up living in an old automobile. At various times, Wagner’s own son and daughter tried to help him, but he repeatedly turned back the offers. At one point, a local realtor in Los Angeles set Wagner up with an apartment, deducting his monthly rent from his Major League Baseball pension check. But when the realtor discovered that Wagner was using drugs again, the arrangement came to an end.

Lou Johnson, the former outfielder who became a driving force for the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT), also tried to help. With the support of BAT, Johnson arranged for funding, including plane tickets and a place in a Florida substance abuse center. But Wagner never showed up for the flight and never made it to the center.

By the early 2000s, Wagner was practically homeless. His “home,” as such, was a small electrical shed, located next to a dumpster. It was in that shed, on a January day in 2004, that Wagner’s lifeless body was found. He was only 69.

Wagner’s story is one of the saddest of any major league ballplayer. His ill fate has led to speculation of why his downfall occurred so steadily over the last decades of his life. Several of his former teammates, including Mudcat Grant, have expressed the belief that Wagner never recovered from the rejection he felt when the Angels traded him. Others have mentioned that Wagner was simply unprepared for life after baseball. Without a college degree, without enough savings, and without the discipline needed to star in the film industry, Wagner floundered.

The story becomes even difficult in light of how much fun Wagner seemed to have playing ball – and how much joy he brought to the fans of Los Angeles and Cleveland. Sadly, Wagner refused to accept the help that he needed, perhaps because of pride or perhaps because he believed he could survive on his own.

Wagner’s story is an all-too-harsh lesson that, as glamourous as life can be for a major leaguer, it can become terrifying once his playing days come to an end.

Addendum: Thanks to some sharp readers, the mystery involving the 1969 Wagner card has been solved. As several readers have pointed out, Wagner is not wearing a Reds uniform in the photograph; he’s actually wearing a Cleveland Indians uniform, which was similar to what the Reds wore in the mid-1960s. Topps airbrushed a Cincinnati “C” over the Indians “C” logo to further create the impression of him wearing Reds colors. The ’69 Wagner is very similar to the 1967 Wagner card; it is essentially a recycled photo from that year, but with the airbrushed white “C” on the cap. Also, the ballpark in the background is Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

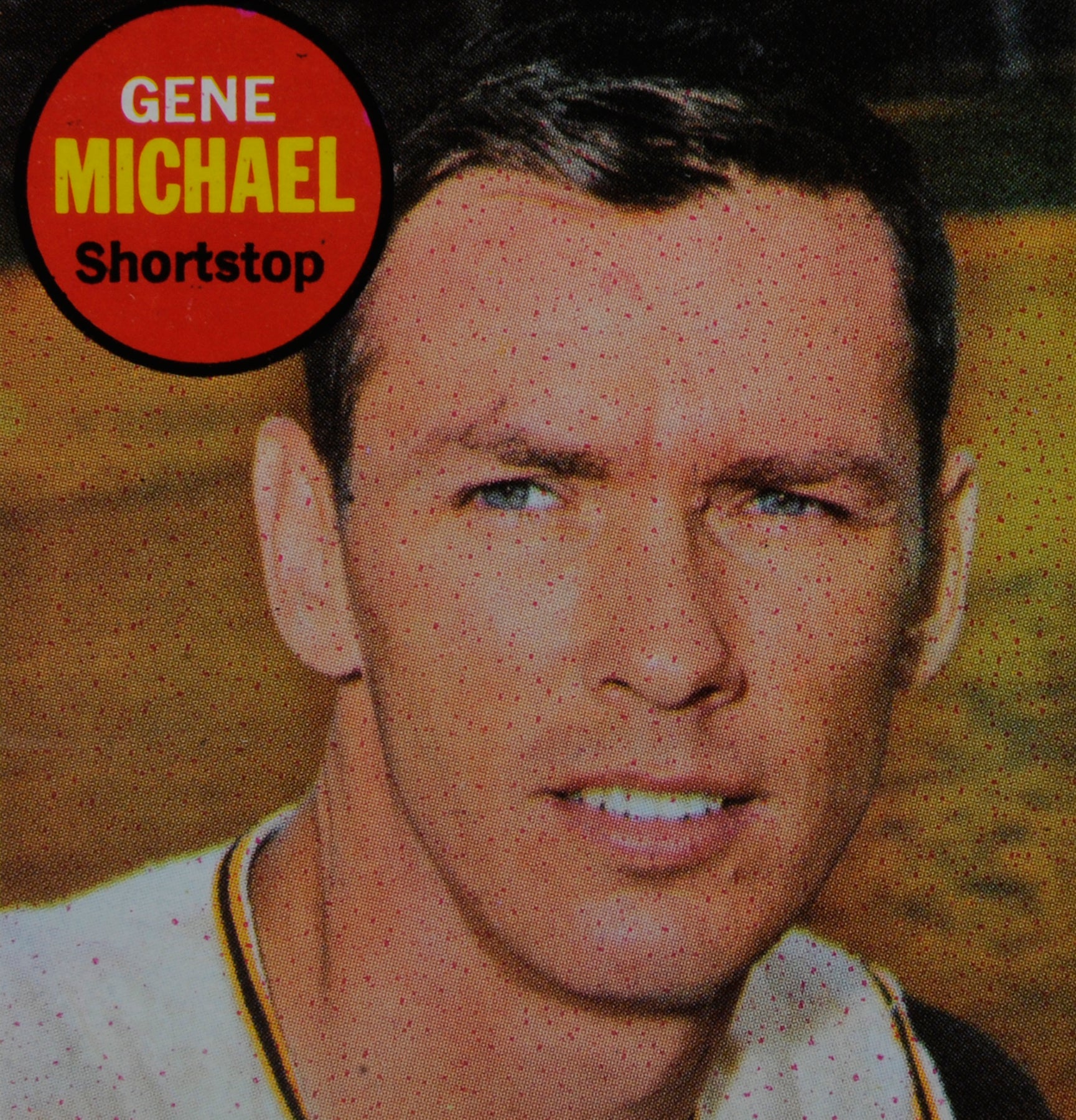

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Chico Salmon

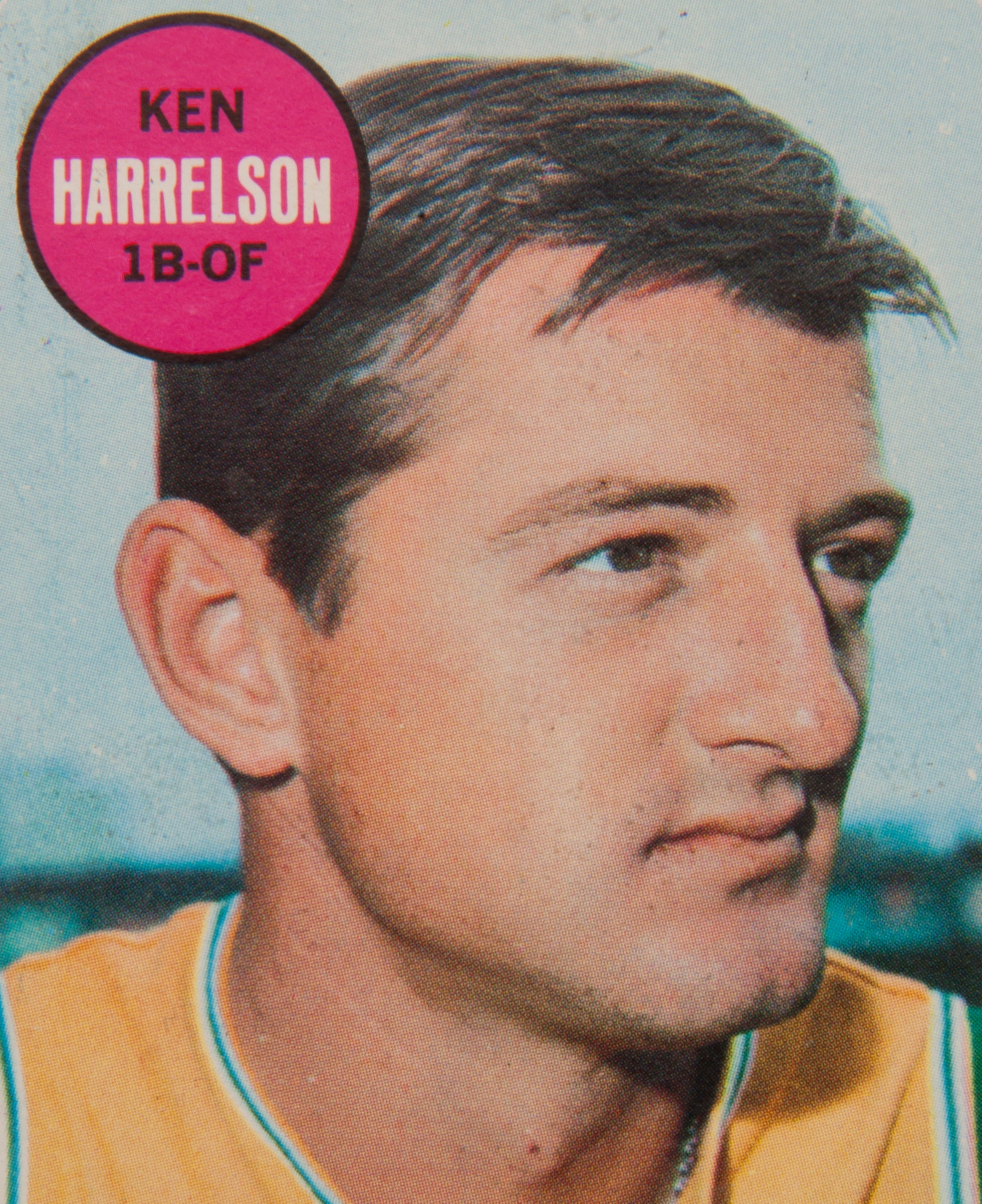

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Hawk Harrelson

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Chico Salmon