#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Joe Schultz

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

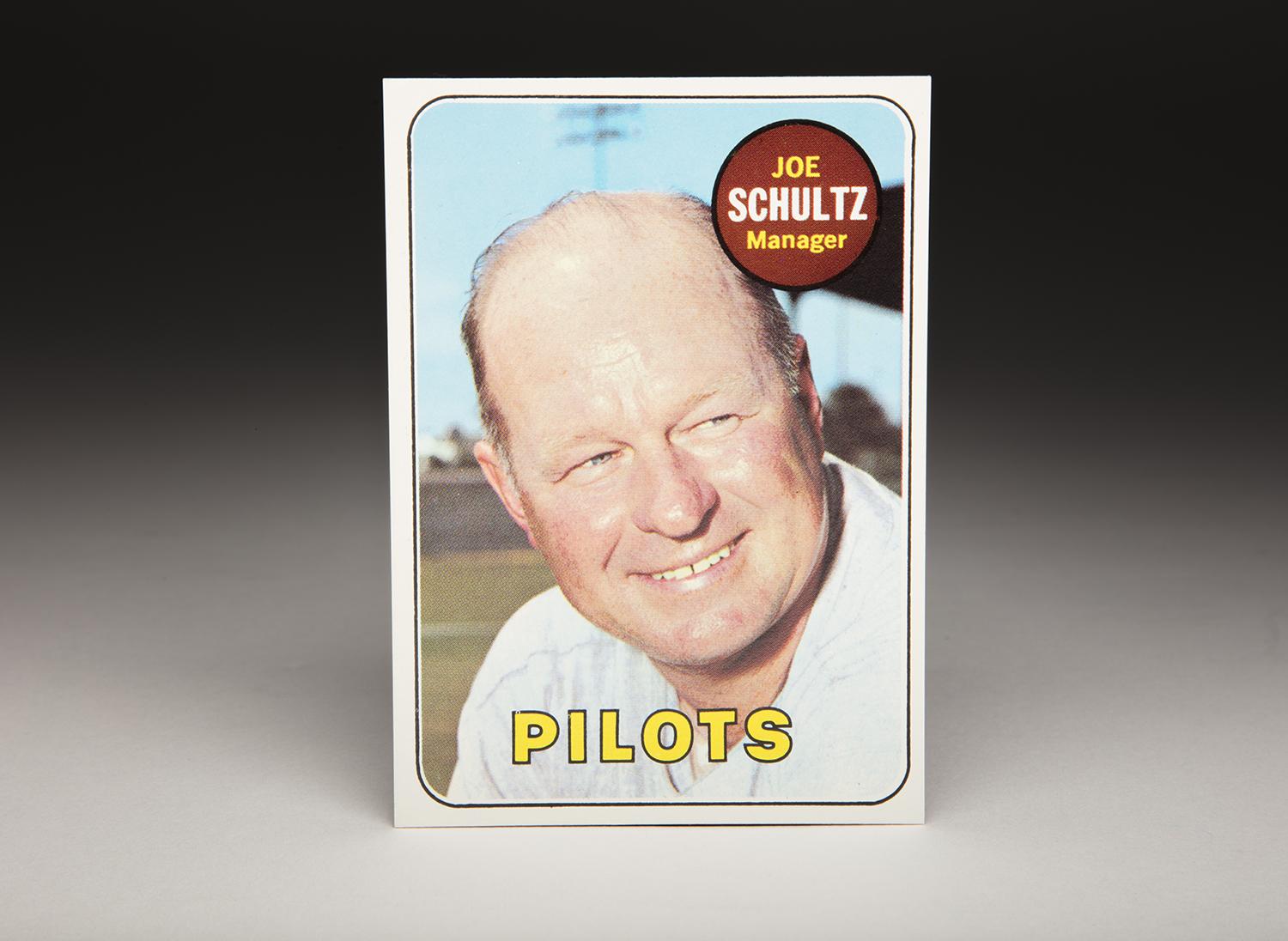

Joe Schultz looks like a happy man on his 1969 Topps card. He seems to have no idea of the nearly impossible situation that he is about to enter: Becoming the first manager in the history of the Seattle Pilots.

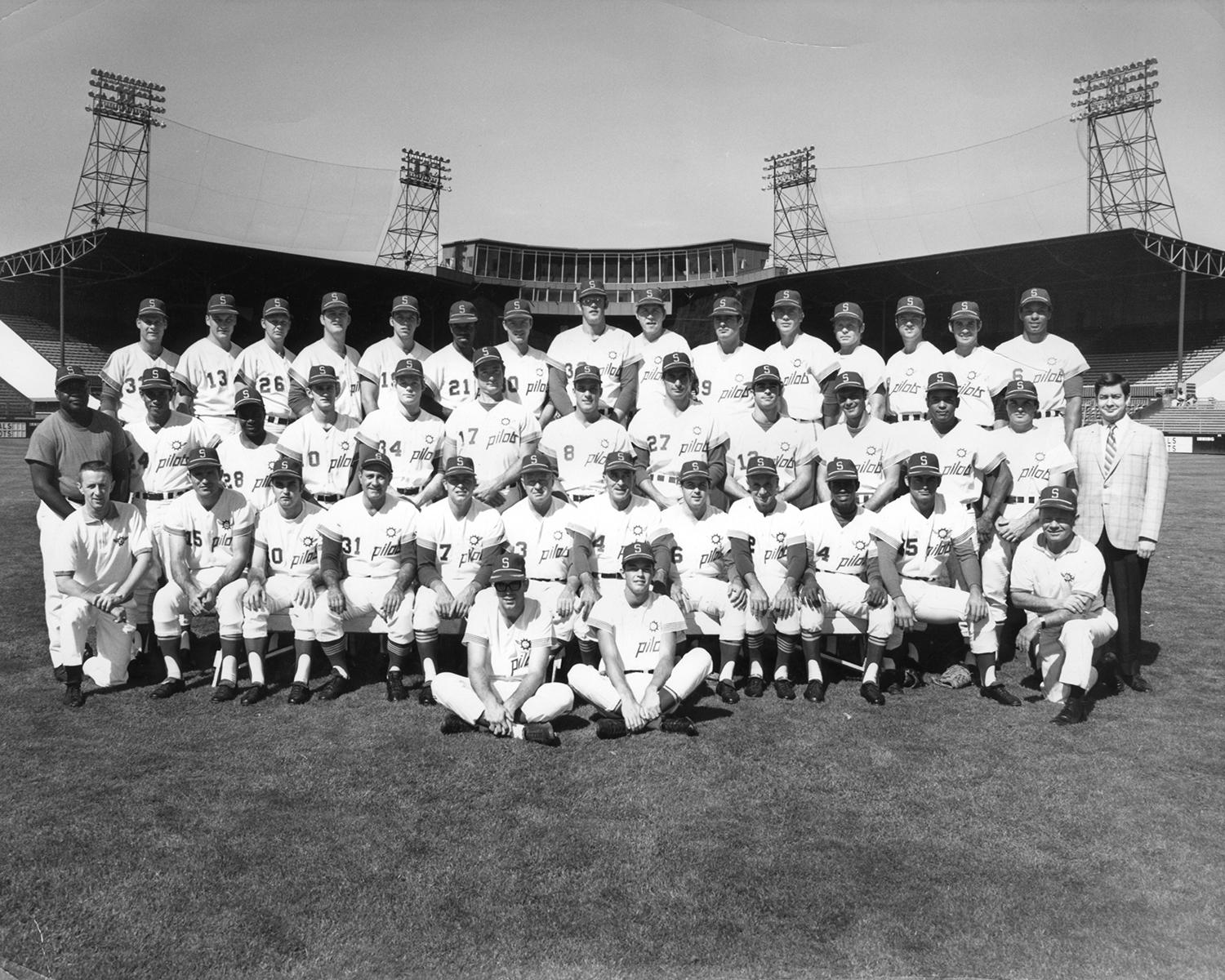

Without much talent, or much of a fan base, or anything approaching a major league quality ballpark, Schultz and the Pilots would slog their way through the first season in franchise history. It would be Schultz’ only season as manager of the Pilots, who fired him at season’s end. In fact, it would be the only season for the Pilots period. That’s because the franchise abruptly relocated to Milwaukee, becoming the Brewers before the start of season No. 2.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

In actuality, Schultz had little idea that he would be managing the Pilots when this photograph was taken by a cameraman at the Topps Gum Company. The photograph is an old one, taken in either 1967 or ’68, sometime during Spring Training, when Schultz was still serving as third base coach of the St. Louis Cardinals. Since the Pilots had yet to play their first game, and had barely reported for Spring Training in 1969, Topps had no updated photographs of Schultz wearing the Pilots’ distinctive blue, yellow and white uniform. Luckily, Topps found an archived photo of Schultz without a Cardinals cap. Given such a generic façade, the card became a suitable fit for Topps’ 1969 set.

As we can plainly see on his Topps card, Schultz had little hair on his head by the late 1960s. I imagine that most of that remaining hair vanished during the 1969 season, as the Pilots piled up loss after loss, frustrating Schultz and his coaches. There is nothing quite like losing to age a major league manager. The Pilots did plenty of losing that summer, dropping 98 games to finish last in the American League West. By the end of the season, Schultz probably could have combed his hair with a towel; a hairbrush might have been rendered obsolete.

While Schultz did not win many games at the helm of the Pilots, he did succeed in forging an image as one of the most colorful managers of the expansion era. Much of that imagery comes from Jim Bouton’s iconic book, Ball Four, which features so many stories about the Pilots’ manager that it could have been alternately titled, The World According to Joe Schultz.

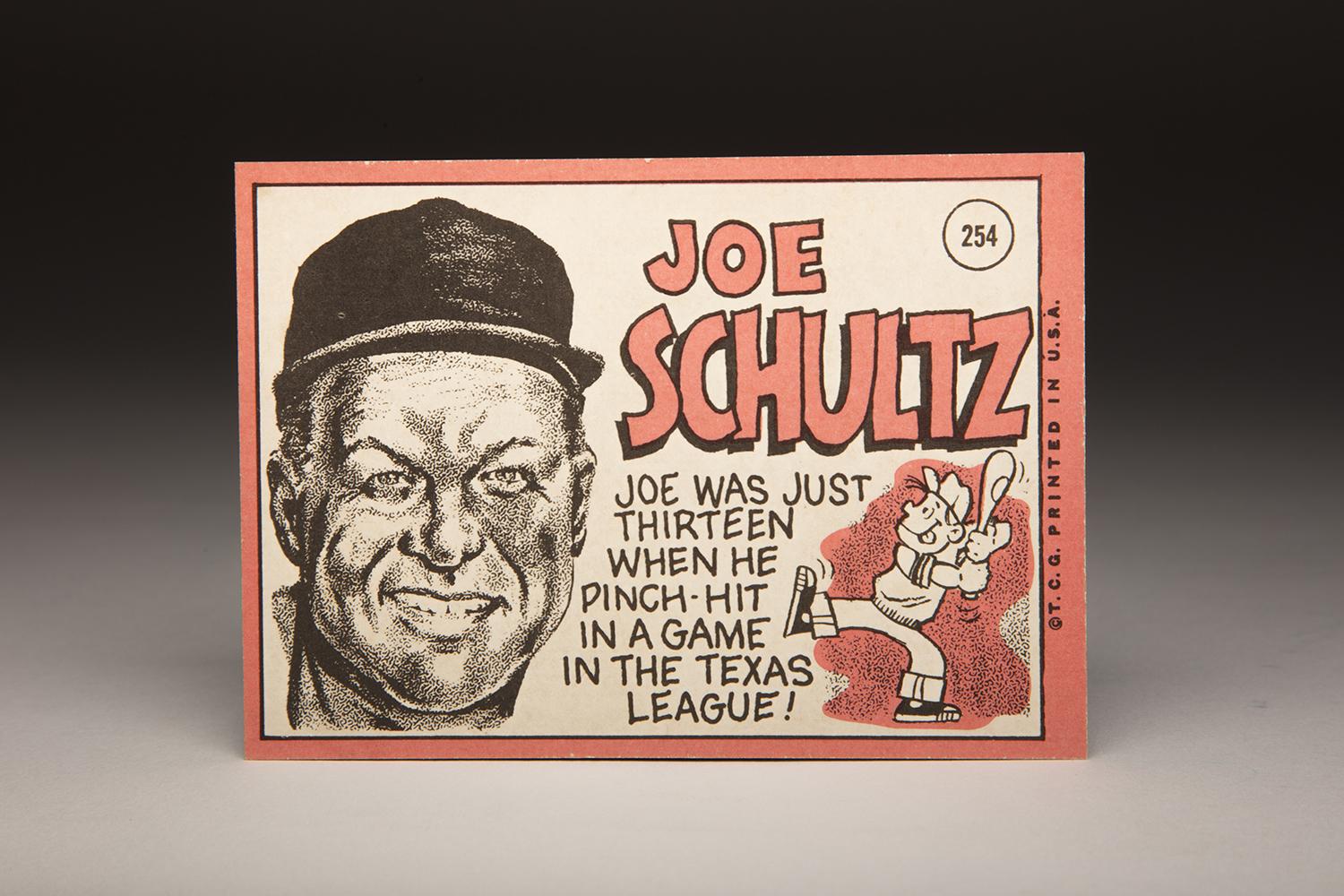

Schultz’s own story in professional baseball began in 1932, when he appeared in his first minor league game – at the age of 13! It’s hard to imagine a 13-year-old taking an at-bat in a professional game, and picking up a single no less, but that’s exactly what Schultz did. In actuality, he was the Houston Buffaloes’ batboy, and only received the call to pinch-hit because his father, the manager of the team, wanted to give him a turn at bat on the final day of the season. Of course, none of this would be allowed in professional baseball today; in order to appear in the minor leagues, players must be at least 16 years old.

Seven years after his celebrated debut as teenager, Schultz would make the roster of the Pittsburgh Pirates, where he played fragments of three seasons as a backup catcher. He later moved on to the old St. Louis Browns, where he lasted six seasons as a part-time catcher and pinch-hitting specialist.

As a player, Schultz had a fairly nondescript career. But he was a smart, hardworking catcher, one who displayed enthusiasm and passion for the game. That reputation earned him a job as a coach with the Browns in 1949. The following season, he turned to minor league managing, something that he did for 13 seasons. In 1963, the St. Louis Cardinals brought him back to the major leagues as their third base coach. Over the next six seasons, Schultz sent home a bevy of runners, as the powerhouse Cardinals won pennants in 1964, ’67, and ’68, and took home world championships in 1964 and 1967.

In the middle of the 1968 season, the yet-to-be-born Pilots approached Schultz about managing the team. For a baseball lifer like Schultz, it was the opportunity that he had been seeking since his coaching career began. Late in the season, the Pilots came to an agreement with Schultz, but could not publicly announce the hiring because he was still committed to coaching the Cardinals, who were on their way to winning the pennant and heading to the World Series. The decision to hire Schultz, rumored since August, became baseball’s worst kept secret.

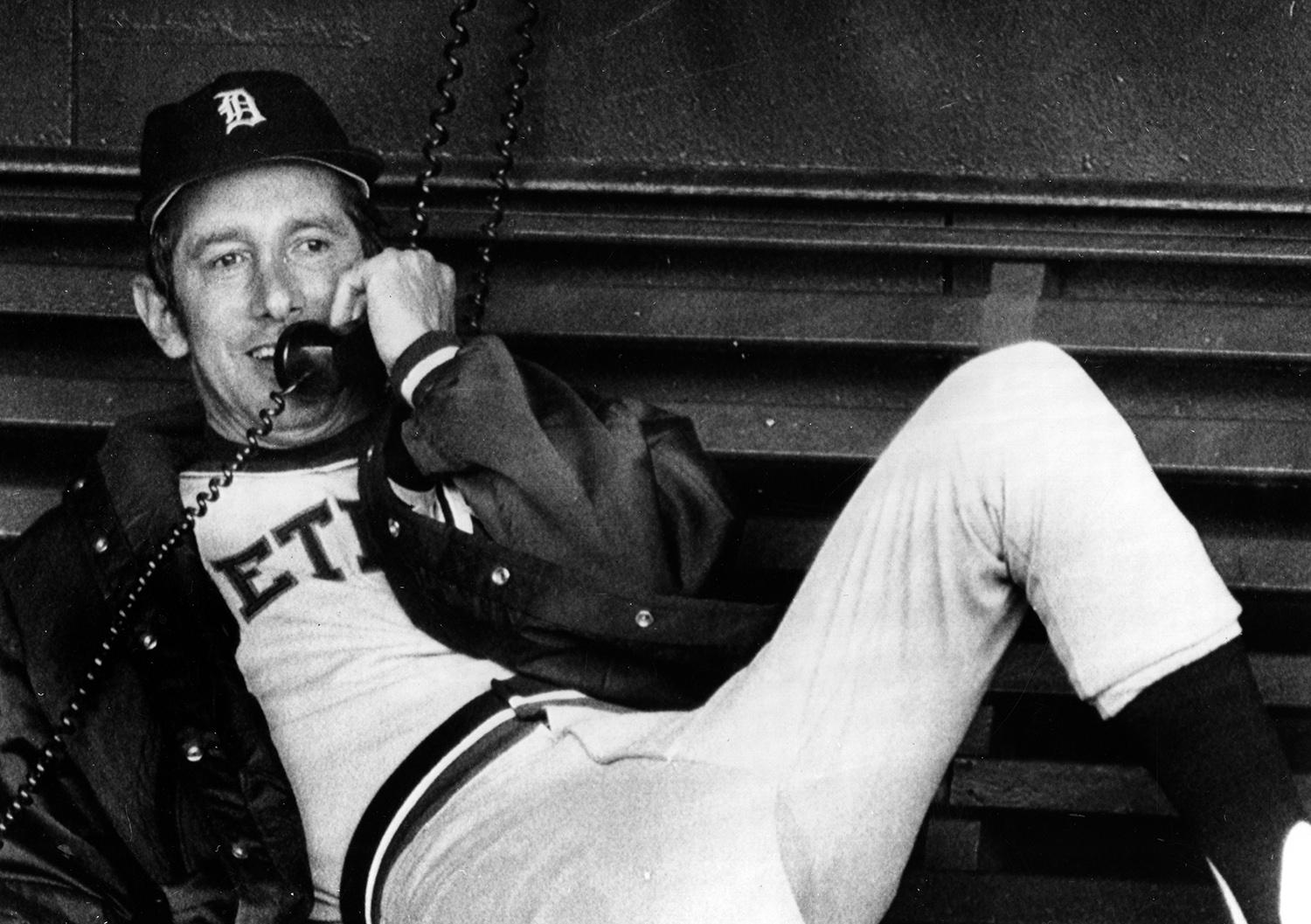

As a result of the rumors, Schultz’ name would come into the national spotlight during the 1968 World Series. As the NBC cameras showed Schultz coaching third base for the National League champion Cardinals, play-by-play broadcasters Curt Gowdy and Harry Caray repeatedly referred to him as the “first manager in the history of the Seattle Pilots.” The longtime broadcasters talked so openly about the Schultz move that it became one of the subplots to the series between the Cardinals and the Detroit Tigers. Finally, during the ninth inning of Game 7, Pilots general manager Marvin Milkes officially announced that Schultz would be managing the Pilots.

At the time, Schultz was a fairly familiar name in the St. Louis area. Rather famously, he had dubbed the 1967 Cardinals as “El Birdos.” But outside of the Midwest, Schultz was a virtual unknown. Many fans regarded him as a mystery man, even though he had already turned 50 and had worked in baseball for the better part of four decades. He was certainly not a household figure, and not necessarily a natural choice to head up the first-year franchise in Seattle.

Schultz and the Pilots hoped to change his level of anonymity. In January and February of 1969, Schultz became a whirlwind on the banquet and speaking circuit, appearing at elementary schools, high schools, luncheons, civic clubs, Fraternal organizations, formal dinners and almost any kind of public function taking place in the Great Northwest. Schultz became a hit on the circuit, captivating audiences with his wisecracking sense of humor, his one-liners and his general enthusiasm for the game. Day after day, he told anyone who would listen that the Pilots were capable of playing winning baseball and finishing as high as third in the American League West. Given his energy and seeming sincerity, people in Seattle began to believe him.

Schultz helped create some general enthusiasm among the Seattle fan base. He also would create a stir in Spring Training, making an immediate impression with his players. When the Pilots showed up to spring camp, they saw a manager who epitomized the old school look of managers in the 1960s. Schultz’ ruddy face, balding pate and rounded physique (all apparent on his 1969 Topps card) looked like something out of central casting.

As a manager, Schultz liked to repeat certain sayings, which reflected some of the simple wisdom that he acquired in nearly 40 years of professional baseball employment. One of his favorites involved his basic hitting advice. “Well, boys, it’s a round ball and a round bat and you got to hit it square.”

Schultz had the kind of vocabulary that seemed appropriate for old-time managers, sprinkled with plenty of four-letter curse words. He had spared his wintertime audiences, including the school groups, such language, but his salty manner of speaking became one of the recurring themes of Ball Four.

In the June 1 entry of Ball Four, Bouton provided some insight into the manager’s colorful way with words. After the Pilots defeated the world champion Tigers, Schultz gave his players a victory speech. Here’s what Bouton wrote: “In the clubhouse Joe delivered his usual speech: ‘Attaway to stomp ‘em. Stomp the [blank] out of ‘em. Stomp ‘em when they’re down… Pound that ol’ Budweiser into you and go get them tomorrow.’ ”

Perhaps the most memorable exchange involving Schultz took place when he visited the mound to talk to journeyman pitcher John Gelnar. Bouton laid out that exchange in Ball Four:

Gelnar was telling us about this great conversation he had with Joe on the mound. There were a couple of guys on and Tom Matchick [of the Detroit Tigers] was up. “Any particular way you want me to pitch him, Joe?” Gelnar asked.

“Nah, bleep him,” Joe Schultz said. “Give him some low smoke and we’ll go and pound some Budweiser.”

Pound some Budweiser. Those three words would become synonymous with Schultz. Over and over, he would implore his Pilots to finish things up and win the game, so that they could go pound some Budweiser. Schultz did enjoy his beer.

Schultz settled into post-baseball life in St. Louis, where he remained for the rest of his years. In 1989, an article in USA Today about the 1964 Cardinals listed Schultz as deceased, even though he was still working for a railway supply company. When Cardinals broadcaster Jack Buck saw Schultz a few days later, he greeted him by saying, “I’m glad to see you’ve been resurrected.”

In actuality, Schultz would live for seven more years, as he maintained a peaceful life in St. Louis. He finally succumbed to heart failure in January of 1996, having lived a rather full 77 years.

During one of the final interviews that he conducted, Schultz was asked about his favorite saying, the one about “pounding some Budweiser.” His response to the Milwaukee Journal was classic Schultz: “I have one in my hand right now.”

Schultz then went on to discuss what might have been, if the Pilots had kept him on and allowed him to move with the team to Milwaukee. Maintaining his usual perspective, Schultz said, “I would have been in a good town with all that beer.”

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame