- Home

- Our Stories

- David Marlin’s donation documents one of baseball’s most memorable home runs

David Marlin’s donation documents one of baseball’s most memorable home runs

Earlier this year, David Marlin visited Cooperstown and was reunited with an old friend.

The longtime Massachusetts-based cameraman, whose acclaim came during a nearly three-decade stint covering the major New England events for CBS News, generously donated one of his beloved cameras to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in 2015.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

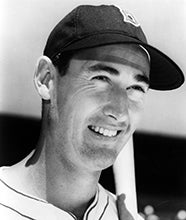

But this camera was special, as it not only was used to preserve numerous history-making moments, both athletic and not, but it also captured the famed Ted Williams homer swatted in his final big league plate appearance.

On Sept. 28, 1960, 42-year-old “Teddy Ballgame” came to the plate with one out and the bases empty in the bottom of the eighth inning. With the 10,454 Fenway Park fans giving their hero a standing ovation, the lefty-swinging outfielder swatted a 1-1 pitch off Baltimore righty Jack Fisher 420-feet over the center field wall.

“Baseball has been the most wonderful thing that ever happened to me,” said Williams that day, “and if I could do it all over again I would want to play for the best owner in the business, Tom Yawkey, and the greatest fans in America.”

Boston would go on to win the 1960 home finale, 5-4, a rare triumphant moment during a challenging 65-89 season. But it was the unforgettable 29th homer of the season and 521st of his career for Williams that was the story. The Splendid Splinter, who had earlier in the season announced the ’60 campaign would be his last, said after the game that he would skip his team’s final three contests of the year to be played in New York.

Williams’ final homer would later be immortalized in literature when John Updike penned “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” a piece that ran in The New Yorker on Oct. 22, 1960. The author’s story, in part, captures the memorable moment:

“Like a feather caught in a vortex, Williams ran around the square of bases at the center of our beseeching screaming. He ran as he always ran out home runs – hurriedly, unsmiling, head down, as if our praise were a storm of rain to get out of. He didn’t tip his cap. Though we thumped, wept, and chanted ‘We want Ted’ for minutes after he hid in the dugout, he did not come back. Our noise for some seconds passed beyond excitement into a kind of immense open anguish, a wailing, a cry to be saved. But immortality is nontransferable. The papers said that the other players, and even the umpires on the field, begged him to come out and acknowledge us in some way, but he never had and did not now. Gods do not answer letters.”

When Marlin and his wife, Elaine, traveled from their Sudbury, Mass., home and visited the Hall of Fame for the first time this past May, he made sure a reunion with the camera was part of the Cooperstown trip.

“I kept the camera all those years. This is almost 60 years later,” Marlin said. “It was 2015 and I said, ‘What am I going to do with this?’ I wrote a letter to Sue Mackay (Hall of Fame director of collections) saying that I know you’re not a photographic history museum, but this is the camera that filmed Ted Williams’ last home run and would you have any interest in the camera. She told me they’d like to have it. I packed it up and sent it off. I could have sold it, but nobody’s shooting film anymore.

“I covered a lot of big stories – the Andrea Doria sinking off Nantucket, Edmund Muskie crying during the 1972 presidential primaries, and Ted Williams’ last home run. People always ask more about Williams than anything.”

What Marlin donated was a 14-pound 16mm Bell & Howell handheld motion picture camera with three lenses, 110-volt motor and cable.

Other cameras donated to the Hall of Fame over the years have included: One used by New York Daily News cameraman Dan Ferrell; one used by Doug McWilliams to photograph baseball players from 1972-1987; a “Big Bertha” camera used for action shots not attributed to a specific photographer; and a Diamond cam used at Coors Field during Game 3 of the 2007 World Series between the Red Sox and Rockies.

“For this basic camera in the mid-1950s, it was $500. It was a lot of money back then,” Marlin said. “The high quality lenses, Sports Finder, motor drive, and custom modifications added considerably to the original cost. The accessories made it functional as a sports camera.

“I used that particular camera to cover baseball, basketball, hockey, and other sports, fast action, where you needed a Sports Finder. I even once covered a submarine firing a missile where we knew where it was going to come up and I was able to follow the missile for a bit with it,” he added. “This was the workhorse for covering local and network television news from about 1948 through the 1960s.”

Marlin, a Massachusetts native, came up as a still photographer, receiving additional training with a motion picture camera in the Army Signal Corps during the Korean War-era, eventually transitioning into shooting local TV news stories before getting his job with CBS in the early 1960s. His footage of Williams was shot for United Press Movietone.

“In the early 1960s, we had all these newsreel companies like Pathé, Universal and Paramount, where people would see the newsreel before a movie,” he said. “But then along came television and the newsreels were only made up two days a week – Monday and Thursday. With television, it was today’s news today and suddenly newsreels were out of favor. One by one they went of business.

“My memories of the Ted Williams home run was there were 10,000-plus in the stands, but it sounded like 100,000 when he hit the home run. I covered the pregame action then I went upstairs and filmed the game. The local guys would go back to their stations to get their pregame stuff on the air. There was only one other guy that stayed, but he covered it from the third base side. But that was the wrong place to cover a left-handed pull hitter. So I was on the first-base photographer’s box.”

Marlin would go on to talk about being hired as a cameraman to film two of Williams’ fishing films – one in Canada and one in Puerto Rico.

“He was tough on the photographers coming out of that dugout, but when he walked into a room heads turned,” he said.

“He could either mesmerize you or tell you off. He never called me by my name – it was always ‘Bush.’ Everyone to Ted Williams was ‘Bush.’ If he used it in a derogatory manner, you were a ‘bush leaguer.’”

Marlin eventually had to make an important transition when camera technology evolved.

“I bought a video camera – I was basically a freelance cameraman – in order to stay in business when the business changed from film to video. It was either hope for documentaries as a film cameraman or go out and buy a video camera. So we did buy it,” he said. “We went to the bank and said we wanted to buy a video camera. The bank said, ‘Okay. How much?’ It was $50,000. He then picked himself off the floor. That’s what it cost initially for the camera, the recorder, the lenses, the whole package. To stay in business that’s what it cost me.

“As a matter of fact, I left the video camera in the trunk of my car for a year. I didn’t trust the video camera. I knew what I was doing with the film cameras.”

Growing up in the Brighton section of Boston, where he could walk to Braves Field and Fenway Park, Marlin called himself a “good field, no hit” ballplayer.

“I couldn’t hit fastballs. I was scared to death. I thought I was going to get killed out there. Who needs this?” he said with a laugh. “Then I took up the camera. Those early years of my youth stimulated my interest in baseball and eventually led me to filming many major baseball stories and Ted Williams’ final home run.”

Now 91, Marlin arrived at the Hall of Fame with a digital camera, the Nikon hanging from a strap around his neck. “I don’t want to give it up. It keeps me going,” he said.

And in a sense, it was Marlin’s skill with a camera instead of a bat that eventually led him to a place in Cooperstown.

“I find that amazing. I was a sandlot outfielder who couldn’t hit and here I am at the Hall of Fame with Ted Williams and all the great ballplayers,” he said with a broad smile. “But not in the same way … it’s just a camera. It just happens to be the camera that filmed a historic event and I thought it belonged here.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

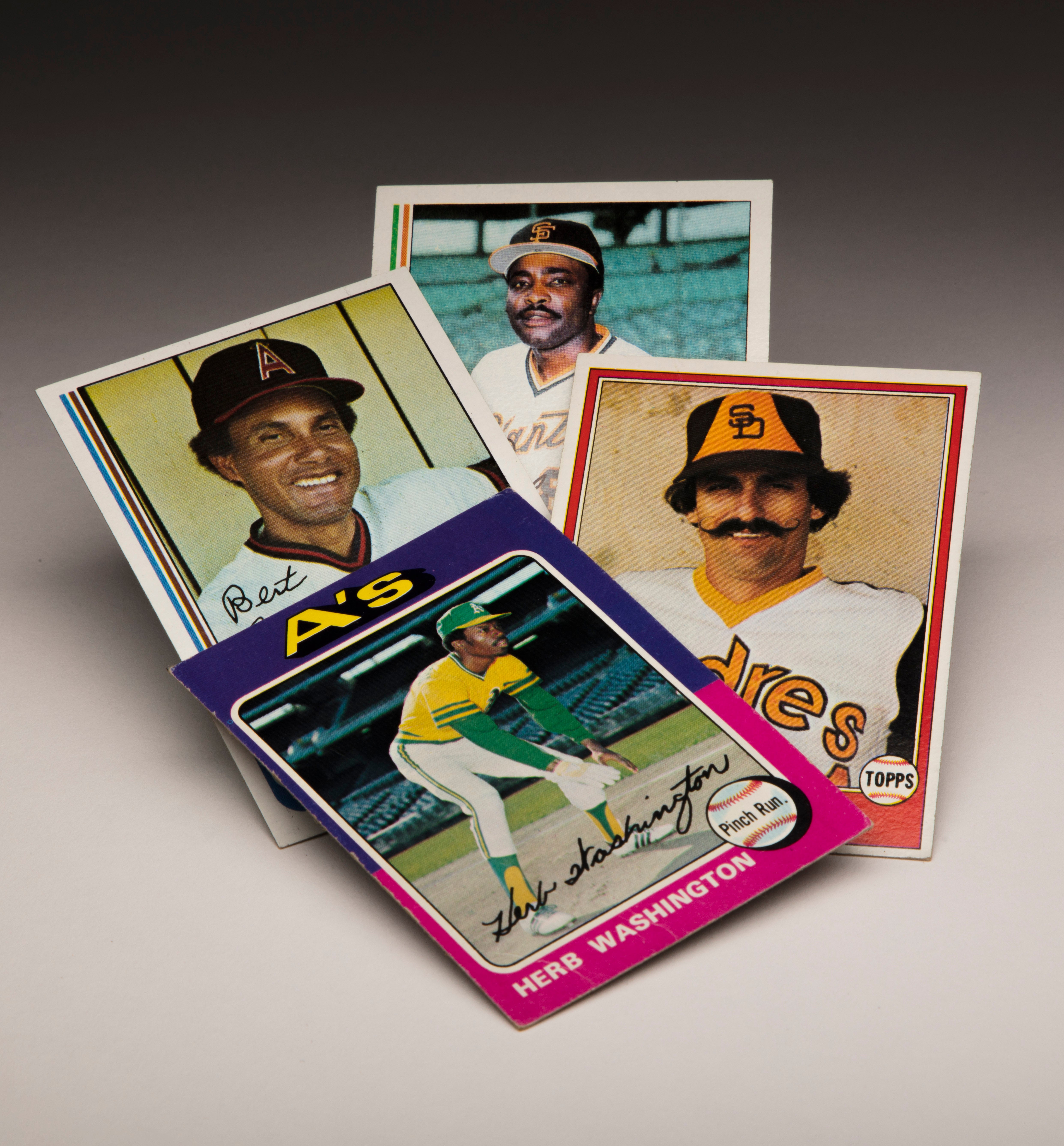

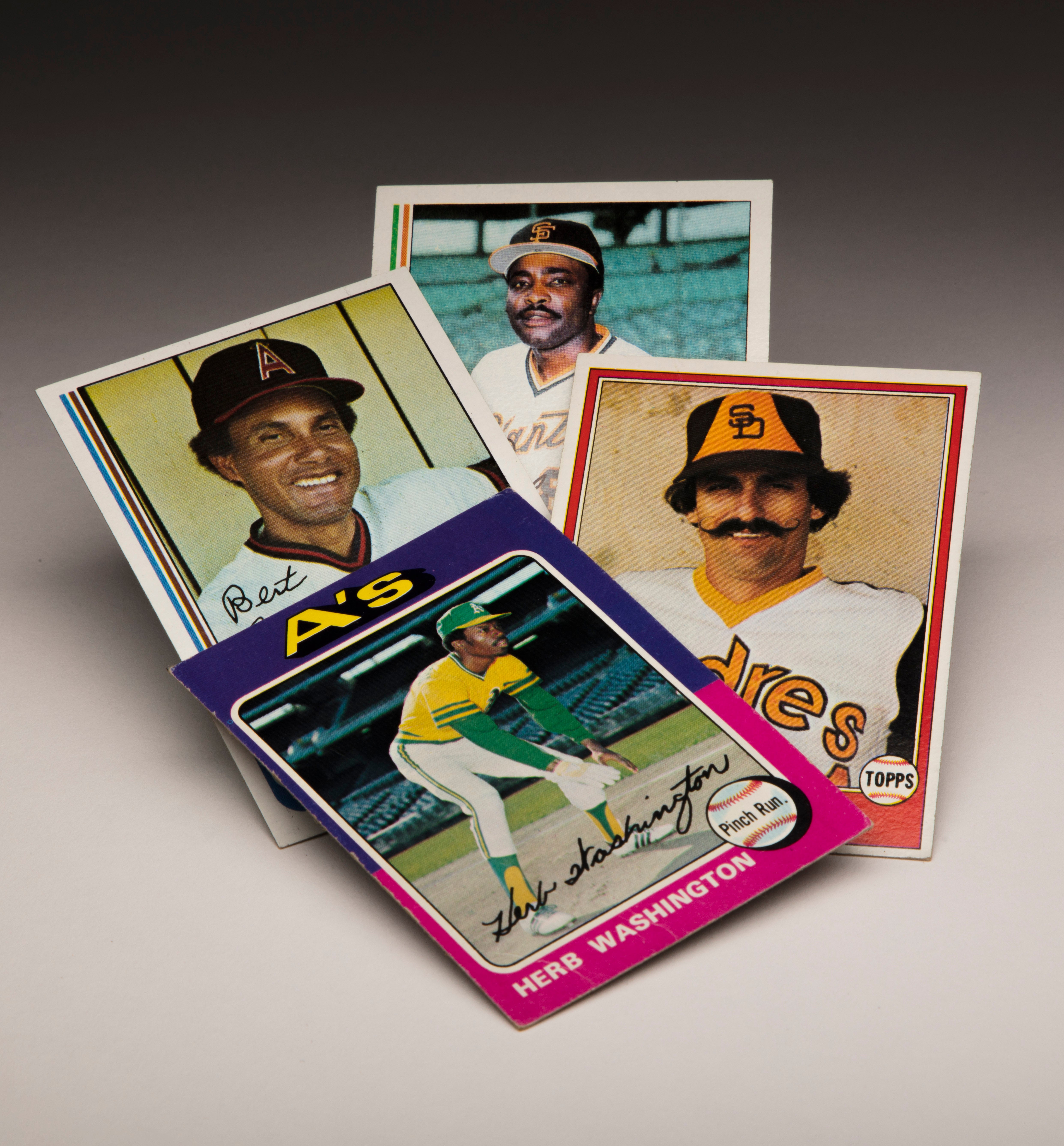

Doug McWilliams’ photographs for Topps have become part of history at the Hall of Fame

Osterhoudt photographs preserved in Hall’s collection

Conlon photos become truly timeless

Historic Photos, Documents of Inaugural Class of 1936 Featured in Museum’s Latest Additions to PASTIME

Doug McWilliams’ photographs for Topps have become part of history at the Hall of Fame

Osterhoudt photographs preserved in Hall’s collection

Conlon photos become truly timeless