- Home

- Our Stories

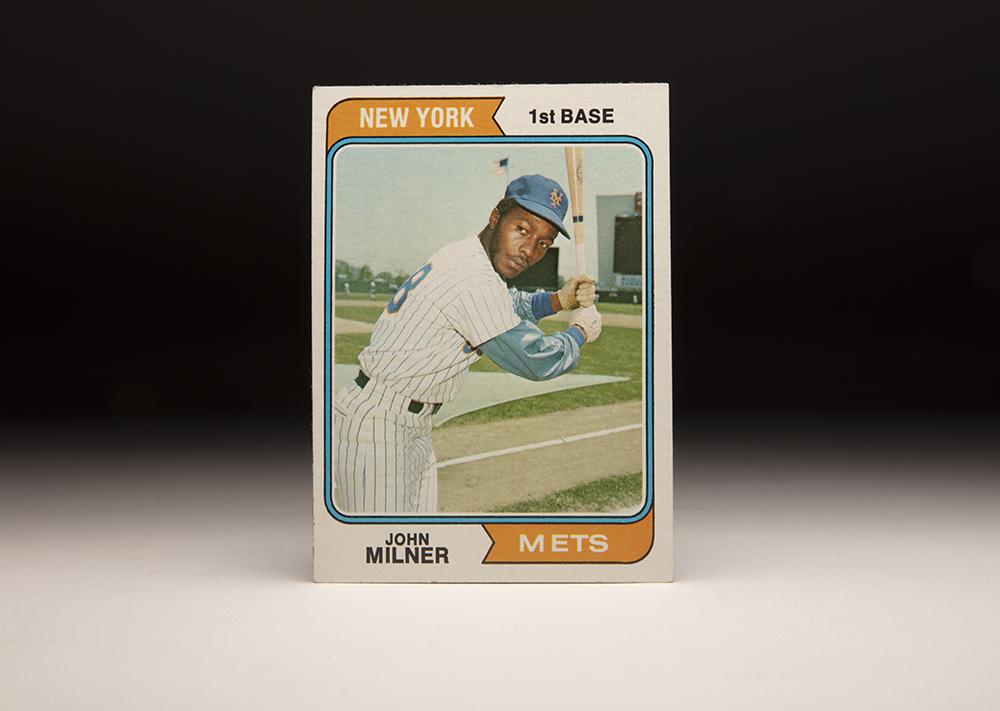

- #CardCorner: 1974 Topps John Milner

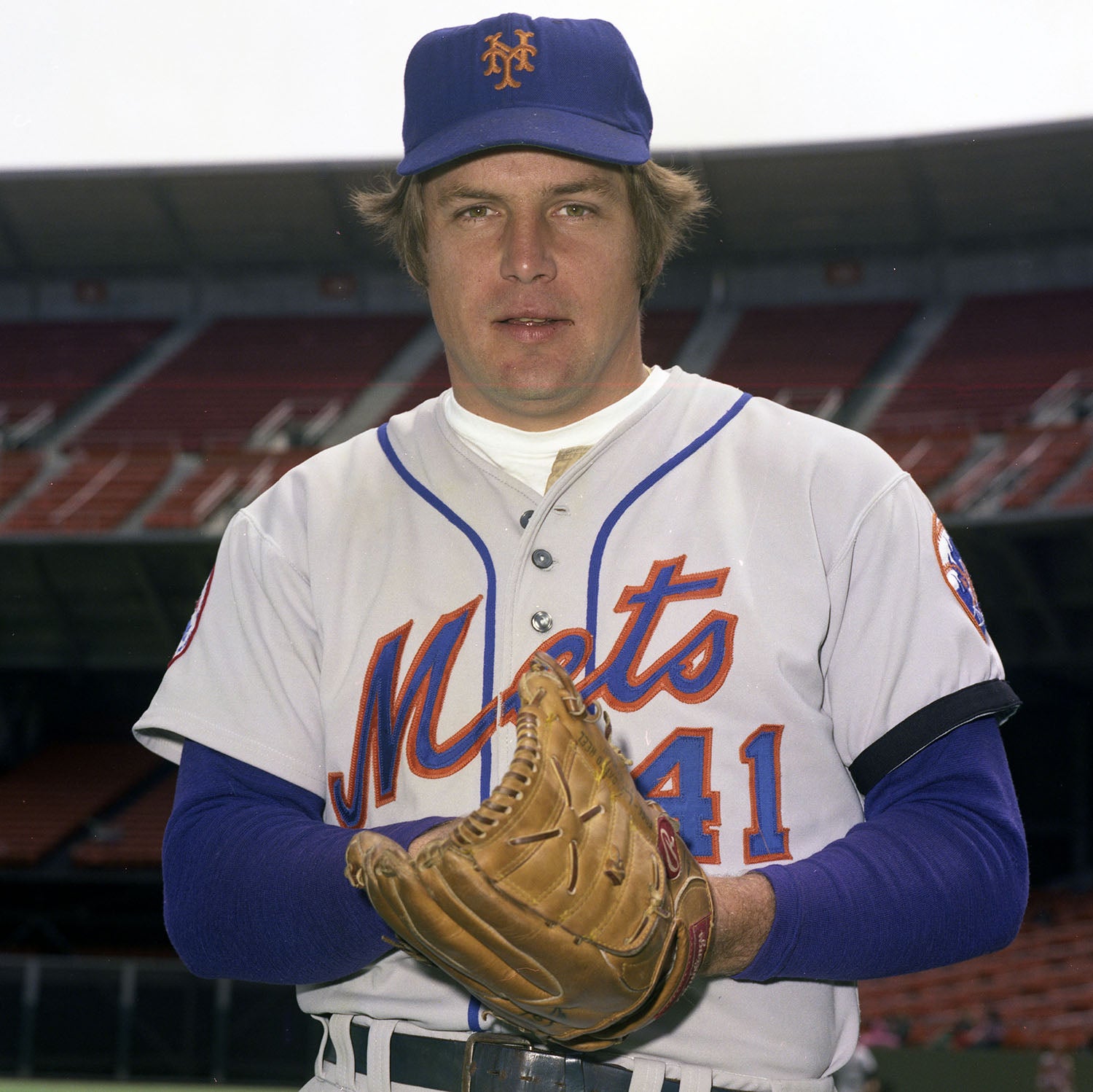

#CardCorner: 1974 Topps John Milner

The picture ran across all six columns of the front sports page of the Pittsburgh Press on Aug. 6, 1979: John Milner, being carried off the field at Three Rivers Stadium by his Pirates teammates after his pinch-hit grand slam defeated the Philadelphia Phillies.

It was a win that propelled Pittsburgh into first place in the National League East and eventually all the way to a World Series title.

For Milner, it was arguably the peak of a 12-year big league career that earned him the nickname “The Hammer” for his powerful left-handed swing and his resemblance to Hank Aaron.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Born Dec. 28, 1949, in Atlanta, Milner starred in baseball, basketball and football – earning All-State notice in all three – at South Fulton High School in East Point, Ga., a segregated school that was no longer in existence by the time Milner established himself in the majors.

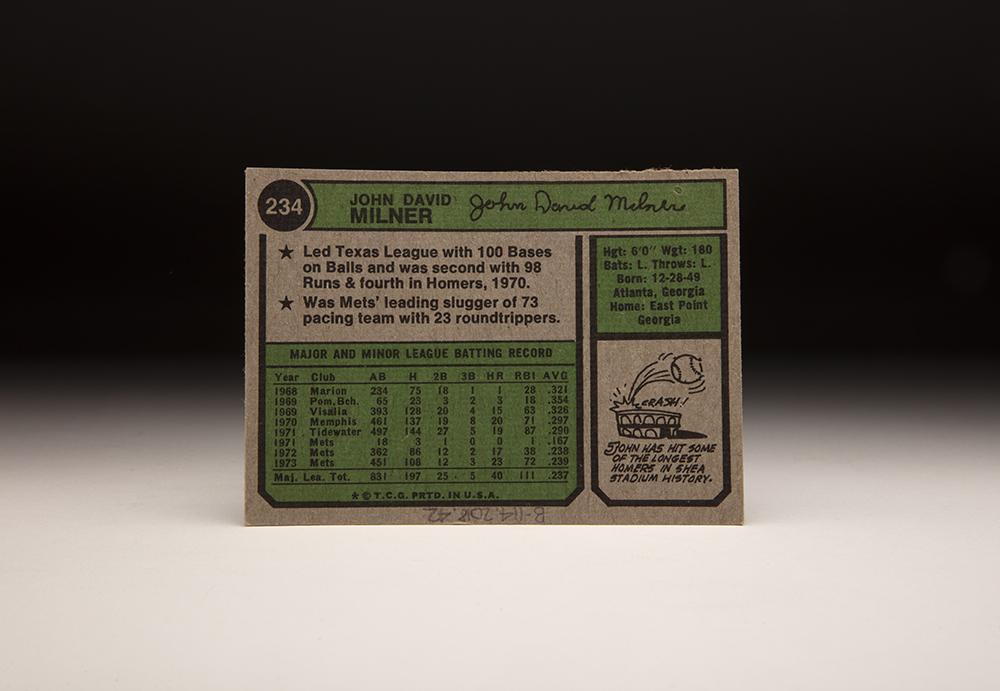

Selected by the Mets in the 14th round of the 1968 MLB Draft, Milner signed and reported to Marion, Va., of the Appalachian League, where he hit .321 with a .422 on-base percentage in 67 games.

“I liked his bat potential and I recommended him,” Mets scout Julian Morgan told the Atlanta Constitution. “Some of our people watched him in a high school all-star game and said: ‘He’s fair.’

“I said: ‘Fair? He’s good.’”

Milner tore through two Class A leagues in 1969, hitting a combined .330 with 18 homers, 81 RBI and 90 walks for Visalia and Pompano Beach. Now earmarked as a top prospect, Milner hit .297 with 20 homers, 71 RBI, 100 walks and 27 stolen bases for Double-A Memphis in 1970, earning the first base spot on the Texas League’s All-Star team.

In 1971, Milner advanced to the Triple-A level, where he hit .290 with 19 homers and 87 RBI for Tidewater. On Sept. 15, Milner debuted with the Mets and appeared in nine games down the stretch, notching three hits in 18 at-bats.

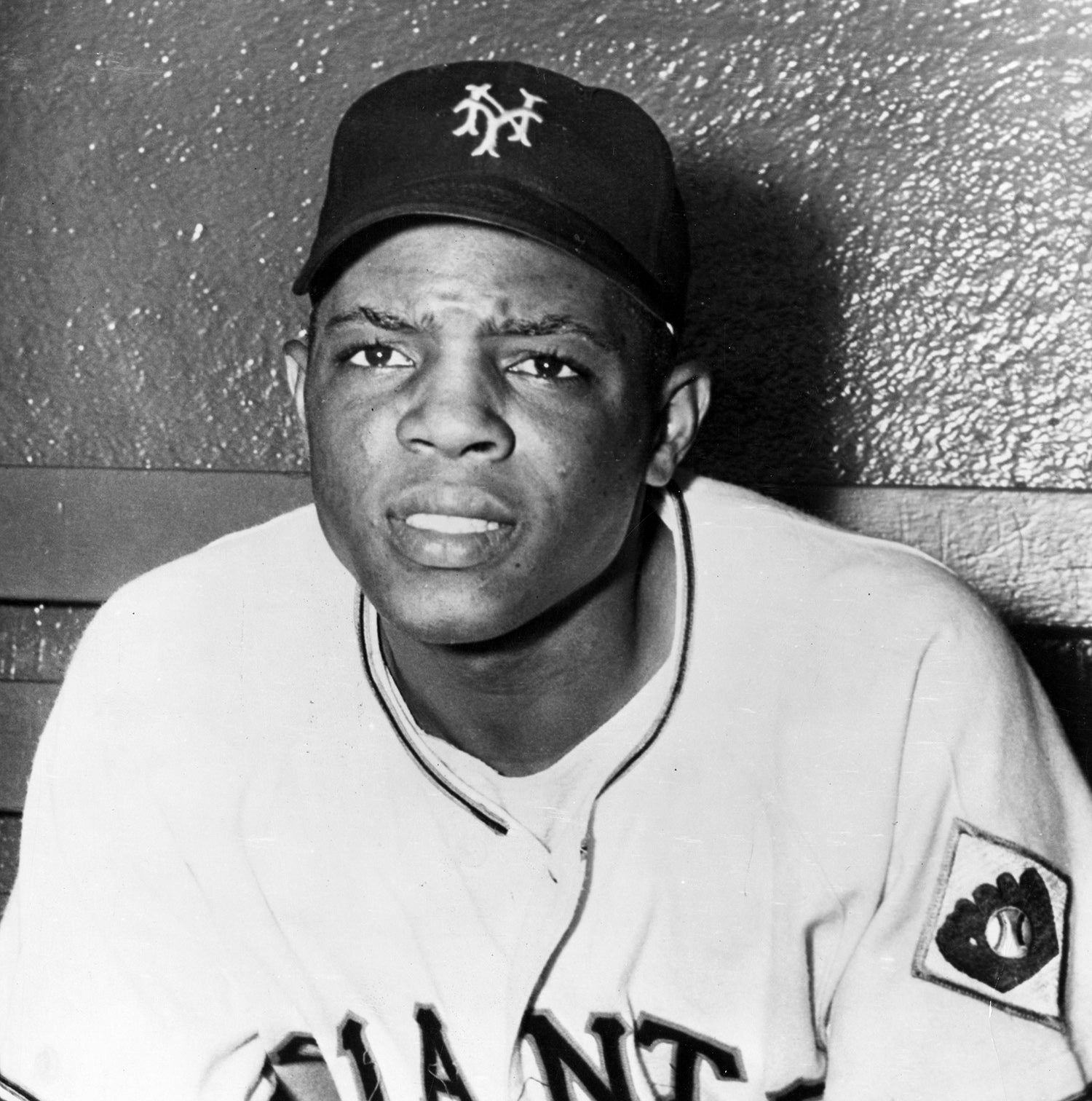

Considered the top young power hitter for an organization that lacked hitting depth, Milner made the Mets’ Opening Day roster in 1972 but was relegated to a bench role with Ed Kranepool ensconced at first base and Tommie Agee, Cleon Jones and Rusty Staub in the outfield. The situation got even more crowded when the Mets traded for Willie Mays on May 11, but Milner forced manager Yogi Berra’s hand with a strong month of June where he hit .338 with six homers and 14 runs scored.

“We figured on him all along,” Mets executive Joe McDonald told the New York Daily News about Milner. “(Director of Player Development) Whitey Herzog says Milner has long been regarded as having the best bat in the organization. We know he’s the fastest man. We run 60-yard sprints in Spring Training to evaluate the speed of our kids in the minors. Two years in a row, John outran everybody. We clocked him in 6.5 (seconds).”

Milner’s batting eye was also among the team’s best, continuing the patient approach he developed in the minors. In eight of his 11 full seasons in the big leagues – the last eight in a row – Milner totaled more walks than strikeouts.

“It’s always been that way,” Milner told the Daily News of his batting approach. “Even when I hit under .300 in the minors, I was hitting good pitches.”

Milner finished the 1972 campaign with a .238 batting average, .340 on-base percentage, 17 homers, 38 RBI and 52 runs scored – good enough for a third-place finish in the National League Rookie of the Year Award voting. Then in 1973, the Mets sent Kranepool to the bench and named Milner their Opening Day first baseman.

That year, the Mets were beset by injuries to stars like Jerry Grote, Bud Harrelson and Jones and stood at 58-70 on Aug. 26. But from there, New York went 24-9 to win the National League East with the lowest win total (82) of a division winner in the modern era. Milner hit .239 with a team-best 23 homers while also adding 72 RBI.

Batting cleanup for much of the season, Milner scored a run and drove in another in the Mets’ 6-4 win over the Cubs on Oct. 1 that clinched the division.

Milner had three hits and five walks in the Mets’ five-game series win over the Reds in the NLCS then added five more walks and eight hits (good for a .406 on-base percentage) in the World Series against Oakland. His ground ball to second that eluded the Athletics’ Mike Andrews plated two runs in New York’s 10-7 win in Game 2 and led to Oakland owner Charlie Finley trying to put Andrews on the disabled list – a move that commissioner Bowie Kuhn vetoed.

Then in Game 5, Milner’s second-inning RBI single off Vida Blue gave the Mets the only run they needed in a 2-0 win that put New York one victory away from the title. But the Mets dropped the next two games to give the A’s the championship.

Milner signed a one-year deal worth a reported $40,000 for 1974 and hit .252 with 20 homers, 63 RBI and 10 stolen bases. But in 1975, Milner suffered a bruised right hand toward the end of Spring Training following a collision at first base with Pirates runner Manny Sanguillén. The injury hampered him throughout April and limited Milner to a .167 batting average for the month.

Groin pulls got the better of Milner later in the season and he appeared in just 91 games, hitting .191 with seven homers and 29 RBI. Then in 1976, the Mets moved Milner to left field and gave Kranepool the majority of the at-bats at first base. Milner hit .271 with 15 home runs, 78 RBI and 25 doubles but battled hamstring injuries and struggled in the outfield.

“People don’t understand I’m playing hurt,” Milner told the Journal News of White Plains, N.Y., after an August game where his defense permitted two runs in a 5-4 Mets loss to Montreal.

The reserved Milner was sometimes seen as uncommunicative with the media and was criticized for being injury prone. But he continued to be a productive hitter, batting .255 with 12 homers and 57 RBI in 1977 despite a shoulder injury suffered when he ran into the outfield fence at Shea Stadium.

“I’m not the first (to suffer repeated injuries),” Milner told the Record of Hackensack, N.J. “If things happen, they happen.”

On Dec. 8, 1977, the Mets continued a team rebuild that began when Tom Seaver was dealt to the Reds that summer. In a four-team deal, New York sent Milner to the Pirates and Jon Matlack to the Rangers, receiving Willie Montañez, Tom Grieve and Ken Henderson in return. The key for the deal for the Pirates was Bert Blyleven – who came over from the Rangers as Al Oliver went to Texas – but Milner wound up being just as important to Pittsburgh’s eventual World Series run.

“In Milner, we are getting a player with power who can play both the outfield and first base,” Pirates general manager Harding Peterson told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “His acquisition gives us back some of the power we lost with the departure of Oliver.”

Milner settled into a platoon role in 1978, spending the majority of his time sharing left field with the right-handed hitting Bill Robinson. Milner batted .271 with six homers and 38 RBI that year and reprised the same role in 1979. But that year, Milner and Robinson formed one of the best platoons in the game – combining for 40 homers, 135 RBI and 111 runs scored. Milner continued to see time at first base in relief of 39-year-old Willie Stargell, who would win the National League Most Valuable Player Award that year. Milner finished with 16 homers, 60 RBI, a .276 batting average and a .373 on-base percentage.

His signature moment came on Aug. 5 in the first game of a doubleheader against Philadelphia. In a back-and-forth game that saw the Phillies take an 8-3 lead for ace Steve Carlton thanks in part to a fifth-inning grand slam by Greg Luzinski, the Pirates battled back and found themselves tied at 8 in the bottom of the ninth. With two outs and the bases loaded against right-hander Rawly Eastwick, Pirates manager Chuck Tanner sent Milner up to pinch hit for catcher Steve Nicosia – who was 4-for-4 at the plate for the game. Phillies manager Danny Ozark countered with lefty Tug McGraw, but Tanner left the left-handed hitting Milner in the game.

Milner hit McGraw’s first pitch over the right field fence to end the contest, and the Pirates won the nightcap 5-2 to complete a five-game series sweep.

“Home plate becomes smaller when they can’t put you on base,” Milner, whose grand slam was the ninth of 10 he would hit in his career, told the Pittsburgh Press. “I was looking for a pitch, an inside fastball, and it came on the first pitch.”

The Pirates finished the season as NL East champions and swept the Reds in the NLCS despite Milner’s 0-for-9 performance. But in the World Series against the Orioles, Milner had three hits and two walks in 11 plate appearances, scoring the game’s second run in a 3-2 Pittsburgh win in Game 2.

The Pirates went on to win the title in seven games.

“The man can play,” Pittsburgh star right fielder Dave Parker told the Associated Press about Milner.

The Pirates could not repeat their “We Are Family” magic in 1980, winning just 83 games as Milner slumped to a .244 batting average with eight homers and 34 RBI – though he did post a solid .378 on-base percentage on the strength of 52 walks.

“I’m not a guesser,” Milner told the AP in describing his approach at the plate. “I wait to see the ball and then I hit it.”

But Milner’s time in Pittsburgh was coming to a close. He was hitting .237 with two homers and nine RBI in 34 games – mostly as a pinch hitter – during the strike-shortened 1981 season when the Pirates traded him to Montreal in a one-for-one deal for Willie Montañez, mirroring the deal that sent him out of New York in 1977. Milner was immediately installed at first base and helped the Expos advance to the postseason, hitting three home runs and driving in nine runs over 31 games. He made two pinch-hitting appearances in the NLDS vs. the Phillies and one more against the Dodgers in the NLCS as the Expos fell one game short of advancing to the World Series.

A pulled muscle near his ribcage sidelined Milner for most of April of 1982, and when he returned he appeared sporadically as a pinch hitter before the Expos released him on July 6. He signed with the Pirates three weeks later and finished the year batting .170 over 59 games – 53 of which came as a pinch hitter. He recorded the 10th-and-final grand slam of his career on Aug. 15 against the Cardinals – becoming the only NL player to record a pinch-hit grand slam in 1982.

On March 28, 1983, the Pirates released Milner, ending his career. He returned to the spotlight, however, in an unwanted way in 1985 when he testified – in exchange for immunity from prosecution – at what became known as the “Pittsburgh Drug Trials” where he detailed using cocaine while he was with the Pirates in 1982.

Milner returned home to Georgia following his career. He died following a battle with lung cancer on Jan. 4, 2000, a week after his 50th birthday.

Over 12 big league seasons, Milner hit .249 with a .344 on-base percentage, 131 home runs and 498 RBI.

“When he first came up, he was as good a prospect as we had and hit the ball harder than anyone in the organization,” Kranepool told the Record following Milner’s passing. “He was a likeable guy who played hard. He came to play every day.

“He just did his job whenever you put him in the lineup.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

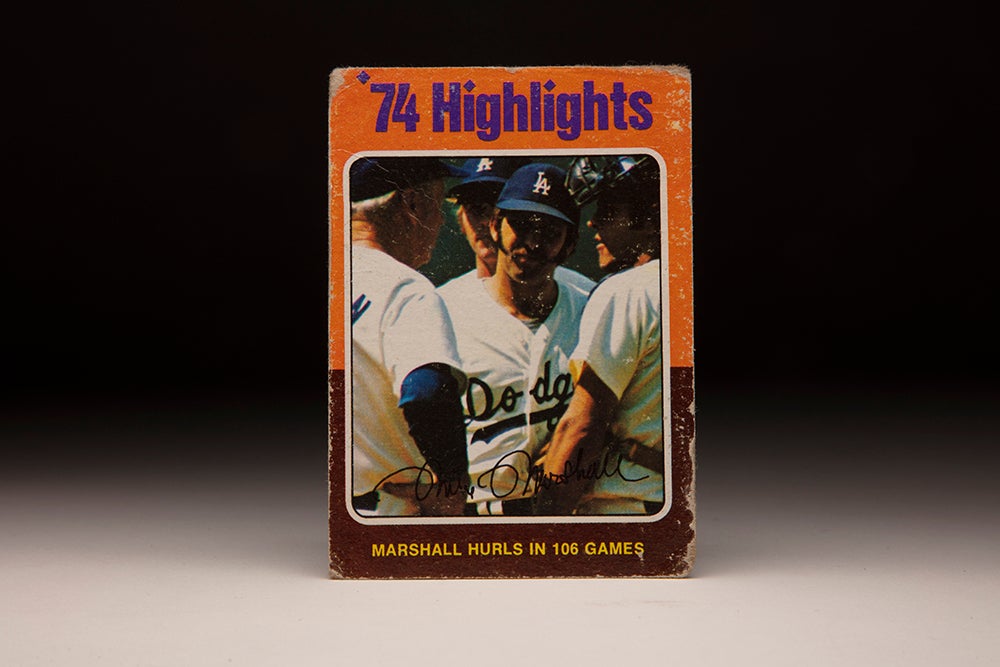

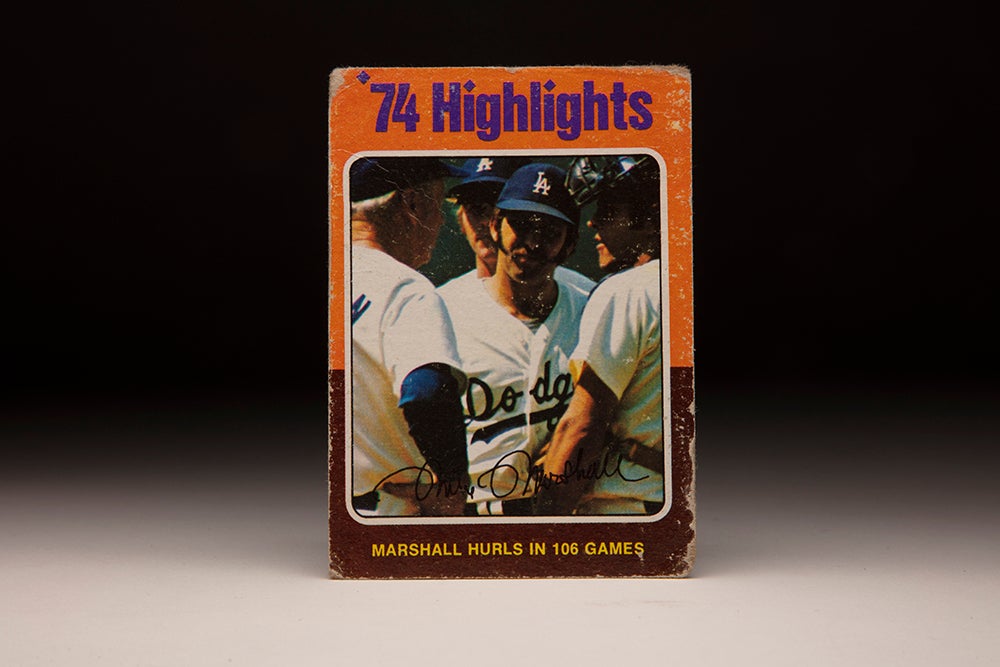

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Mike Marshall

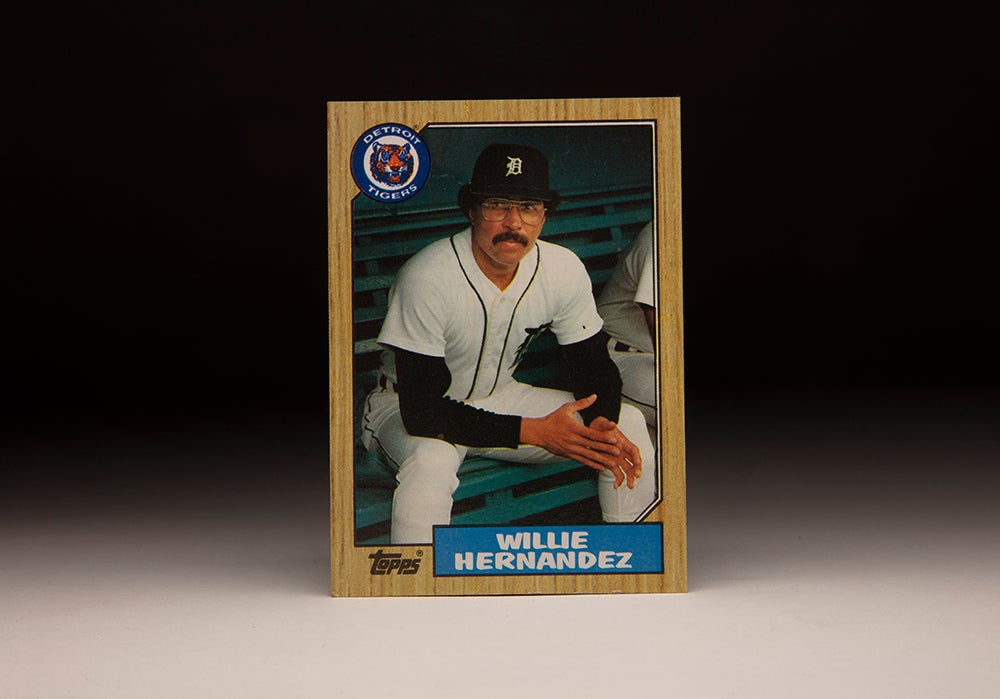

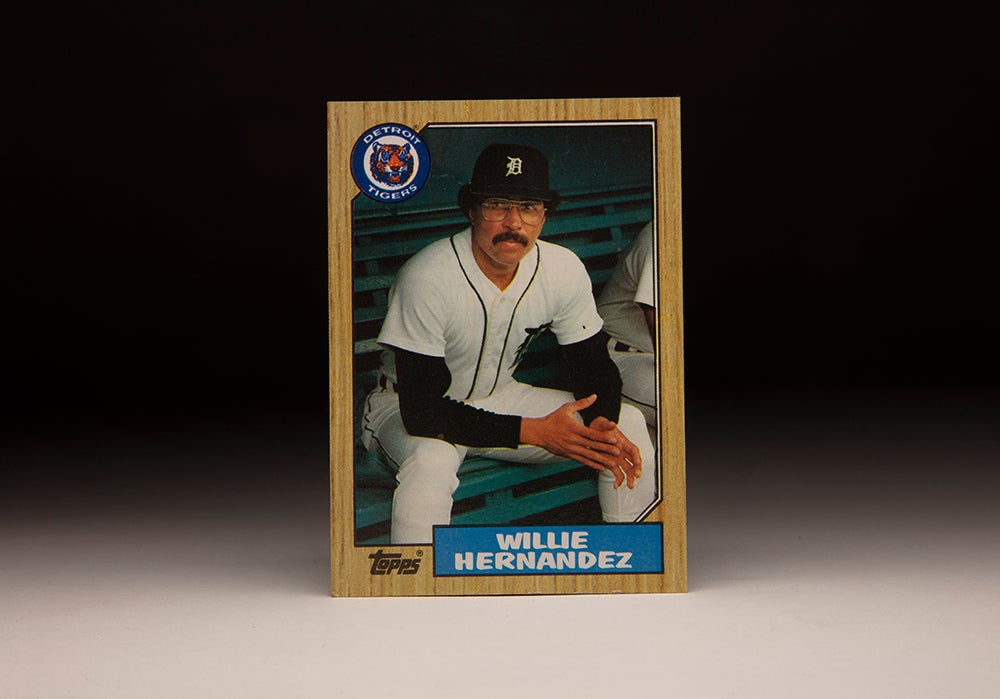

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Willie Hernández

#CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Jody Davis

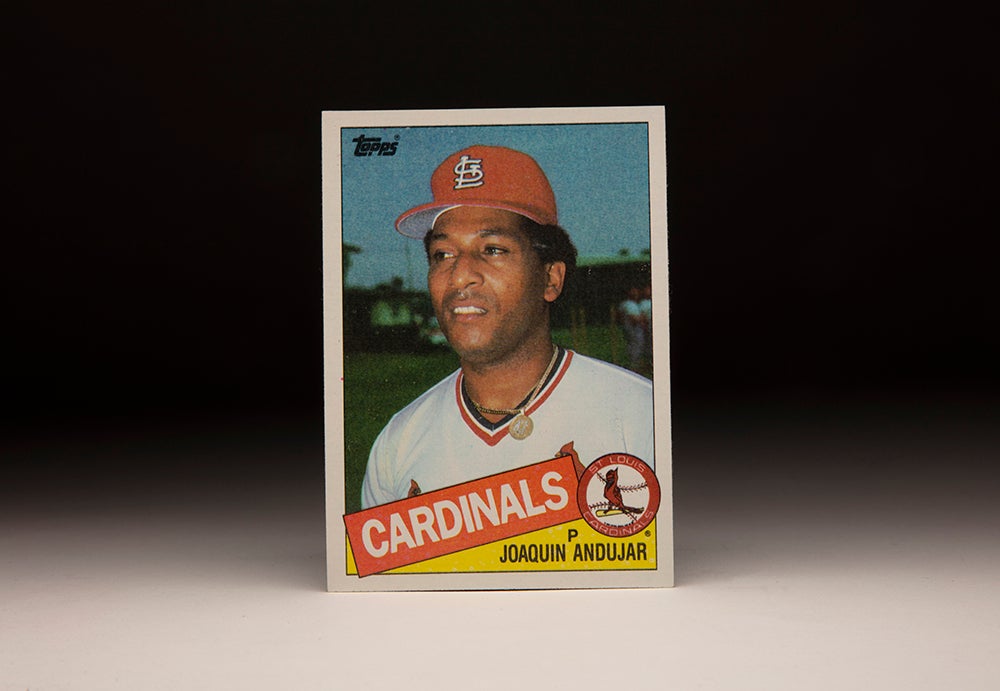

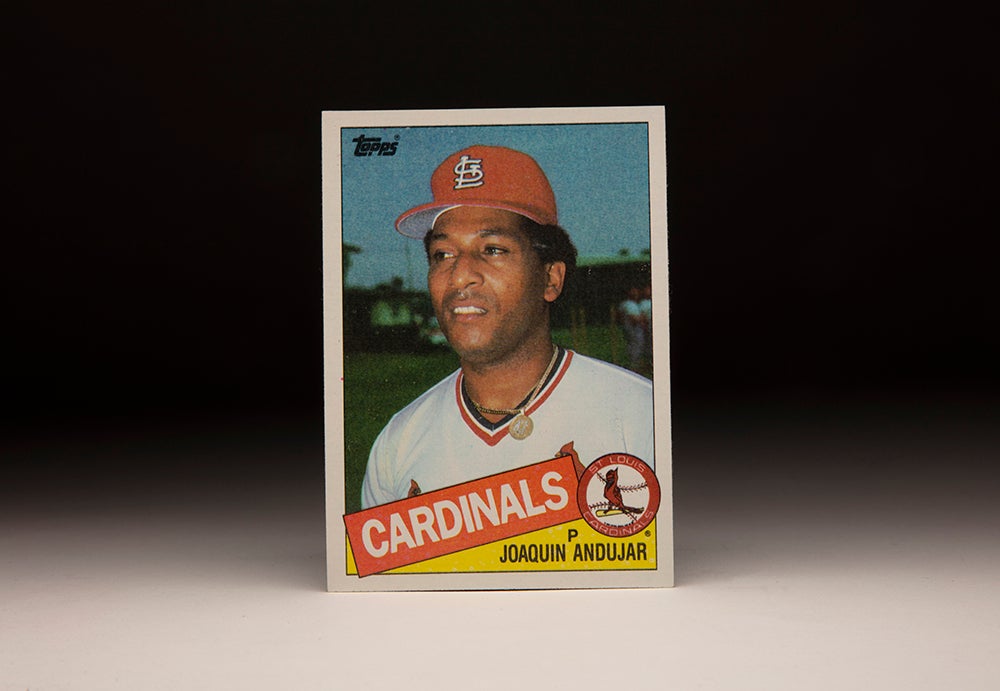

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Joaquín Andújar

#CardCorner: 1975 Topps Mike Marshall

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Willie Hernández

#CardCorner: 1982 Donruss Jody Davis