- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1985 Topps Joaquín Andújar

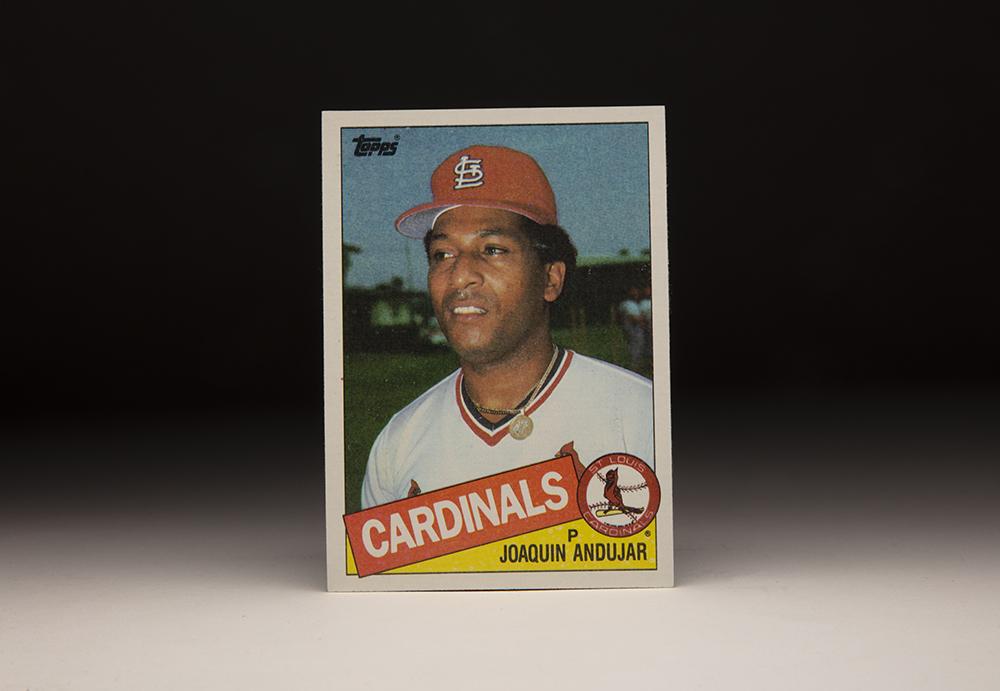

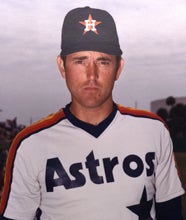

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Joaquín Andújar

He took the mound during two of the most famous Game 7s in Cardinals history, one playing the hero and another in one St. Louis fans would like to forget.

Before, during and after those games, Joaquín Andújar always seemed to be at the center of the action.

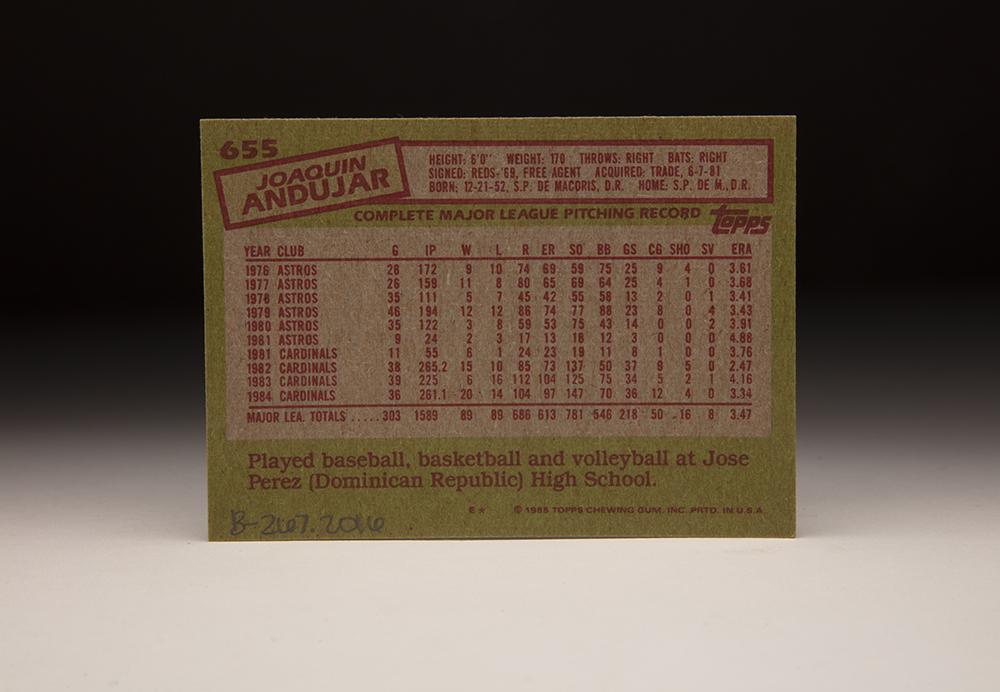

Born Dec. 21, 1952, in San Pedro de Macoris in the Dominican Republic, Andújar was the only child in a family whose breadwinner was a sugar mill worker. Raised by his grandparents after his parents separated, Andújar was in the same high school class with two other future big leaguers, Santo Alcalá and Arturo DeFreitas, and signed with the Reds as an amateur free agent on Nov. 14, 1969.

Reporting that spring as an outfielder, Andújar was moved to the mound to take advantage of his live right arm. After pitching in rookie ball in 1970 and the Class A Northern League in 1971 – he struck out better than a batter per inning at both stops but battled control problems and his own temper – Andújar made it to Double-A in 1972, where he went 7-6 with a 3.54 ERA and 101 strikeouts in 112 innings with Trois-Rivieres.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

After splitting the 1973 season between Double-A and Triple-A, Andújar went 8-8 with a 3.57 ERA for Indianapolis in 1974 before posting a 6-2 record in the Dominican Winter League, tying with J.R. Richard for the league lead in strikeouts.

Andújar earned an invitation to the Reds’ Spring Training camp in 1975 and impressed executives and observers alike with his fastball.

“You won’t find many better arms anywhere than the one Andújar has,” Scott Breeden, the Reds’ minor league pitching instructor, told the Tampa Times in the spring of 1975.

But despite near-unanimous acclaim by Reds’ executives that he had the best arm in the system, Andújar was sent to Triple-A to start the 1975 season – joining top prospects like Rawly Eastwick, Ray Knight and Joel Youngblood who were unable to crack the deep Reds roster.

“What he needs to do is control himself and the baseball,” Reds farm director Chief Bender told the Tampa Times, “and he’ll be a good major league pitcher.”

Indianapolis’ roster was in fact so deep that Andújar never pitched a game for them in 1975 and was sent back to Trois-Rivieres to get work – a demotion blamed at least in part on Indianapolis manager Vern Rapp, who did not appreciate Andújar’s passionate style. He went 4-8 in 62 innings for Trois-Rivieres before the Reds traded him to the Astros on Oct. 24 in exchange for two players to be named later who became Luis Sánchez and Carlos Alfonso.

With the help of minor league pitching coach Hub Kittle – who recommended the Astros trade for Andújar and who would one day be Andújar’s big league coach and mentor in St. Louis – Andújar made the Astros’ Opening Day roster in 1976 and pitched his first two games out of the bullpen, both against the Reds, on April 8 and 11. He moved into the starting rotation the next week and struggled with his command before notching his first big league win on June 1 – again against the Reds.

“Every dog has his day,” Reds manager Sparky Anderson told the Cincinnati Post after Andújar’s two-hitter against Cincinnati in a 2-1 Houston win. “Let’s wait until the end of the season and then take a look at Andújar’s Ws and Ls.”

Twenty days later, Andújar beat the Reds again – tossing another complete game and this time shutting out the Big Red Machine. And in his next start, he notched another complete game win over Cincinnati. The Reds won 102 games and the World Series title that year, and Andújar was the only pitcher to record three complete game wins against them.

He finished the season with a 9-10 record and 3.60 ERA over 172.1 innings, posting nine complete games and four shutouts, the latter tied for the top mark among all rookie pitchers.

“You have to be lucky in the majors,” Andújar told the Palladium-Item of Richmond, Ind. “I was lucky this year. I knew I would be sometime. All I needed was a chance and Houston gave me a chance."

Andújar began the 1977 season with a three-hit shutout of Atlanta in the Astros’ second game of the season then reeled off six straight wins from mid-May to mid-June.

“The guy is wired,” Astros teammate Bob Watson told United Press International as Andújar made national headlines for his pitching that summer. “I love to play the game when he is pitching. He is excited every time he goes to the mound and every time he goes up to hit.”

Andújar was 10-5 with a 3.47 ERA following a win over the Dodgers on July 14. But he aggravated a lingering hamstring injury in that game and was not able to make his scheduled appearance at the All-Star Game at Yankee Stadium.

The bad left leg sidelined Andújar until September and he finished the year with an 11-8 record and 3.69 ERA in 158.2 innings over 26 appearances.

Andújar was hobbled with another hamstring pull during the summer of 1978, costing him six weeks. When he returned from the disabled list, Houston manager Bill Virdon moved Andújar to the bullpen. He finished the season with a 5-7 record and 3.42 ERA over 110.2 innings.

Andújar began the 1979 season in the bullpen but moved into the rotation in late May. He was named the National League’s Pitcher of the Month for June when he went 5-1 with five complete games and a 1.59 ERA in six starts.

But on July 4 against the Reds, Andújar was involved in a bench-clearing incident after Cincinnati took exception to a pitch that was a little too close to Joe Morgan. Bill Bonham retaliated by throwing a pitch behind Andújar in the sixth inning, leading to the fracas when Andújar yelled at Bonham after a groundout out and Ray Knight intervened. Knight and Andújar had been involved in a hotel fight when the two were roommates with the Reds’ Double-A team in Trois-Rivieres.

“Andújar’s a hyper person,” Astros teammate Enos Cabell told the Cincinnati Post. “As long as he doesn’t hurt anyone, we don’t care what he does. We don’t care if he goes crazy so long as he goes out and wins.”

Andújar did win the game against the Reds to improve to 10-4 on the season and was named to his second All-Star Game. He pitched two innings in the National League’s 7-6 win at the Kingdome – but he won only twice more the rest of the campaign, and Houston moved him back to the bullpen in September. Andújar finished the year with a 12-12 record, four saves and a 3.46 ERA over 194 innings.

The Astros entered the 1980 season as the favorites to win the National League West, powered by a projected rotation that featured free agent acquisition Nolan Ryan to go along with J.R. Richard, Joe Sambito, Ken Forsch and Andújar. But once again, the Astros shuttled Andújar between the bullpen and the rotation, and he finished the year with a 3-8 record and 3.91 ERA over 122 innings.

Houston, however, fulfilled its pedigree and won the division for the first time after defeating the Dodgers in a one-game playoff. In the NLCS, the Phillies and Astros battled in a tense five-game series that featured extra innings in the final four games. Andújar closed out Houston’s 7-4 win in Game 2 with a save but did not pitch again – and the Phillies advanced to the World Series.

After once again filling the role of spot starter/reliever during the first two months of the 1981 season, Andújar was traded to the Cardinals on June 7 in a one-for-one deal for outfielder Tony Scott.

“We got an experienced guy who can do both spot starting and middle relief,” Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

When Andújar made his first appearance with the Cardinals after the strike was resolved, he was used in relief. But he moved into he rotation and made all but two appearances as a starter the rest of the way, going 6-1 with a 3.74 ERA for St. Louis – including a 3.42 ERA as a starter.

He signed a three-year deal with St. Louis prior to the season, won a spot in the Cardinals’ 1982 rotation the following spring, threw a shutout against the Phillies in his third start of the year and pitched St. Louis to a division title in September, going 5-0 in his final six starts with a 2.13 ERA.

Andújar started Game 1 of the NLCS vs. the Braves and allowed one run over five innings. But with one out in the bottom of the fifth and Atlanta leading 1-0, the game was delayed by rain and eventually called off, negating all statistics and necessitating another Game 1 the following day. Andújar then started what became Game 3 of the NLCS and shut out Atlanta through six innings before allowing two runs in the seventh in a 6-2 St. Louis win that clinched the series.

In the World Series, Andújar started Game 3 against Milwaukee and was working on a two-hitter with one out in the seventh inning when Ted Simmons lined a ball off Andújar’s right leg just below the knee. Andújar dropped to the ground in pain and was taken by ambulance to a hospital while Jim Kaat, Doug Bair and Bruce Sutter combined to finish the Cardinals’ 6-2 victory.

“Joaquín’s calmed down a lot,” Cardinals first baseman Keith Hernandez told the Associated Press after Game 3. “He used to be much more temperamental. Now he’s calm and cool. He’s become a pitcher.”

But there was a real question in the days following Game 3 if Andújar would be able to pitch again in the Fall Classic. Milwaukee won Games 4 and 5 to advance to the precipice of a title – and Herzog called on rookie John Stuper to start Game 6 against future Hall of Famer Don Sutton.

With the odds against them, the Cardinals backed Stuper with seven runs over the first five innings and then blew the game open with six runs in the sixth en route to a 13-1 win. And Andújar said he would be able to start Game 7.

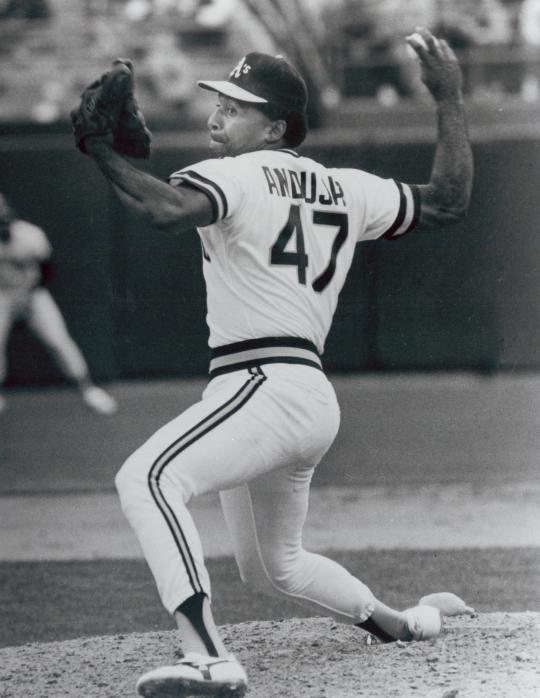

A throwing error by Andújar led to two runs (one earned) in the top of the sixth of Game 7, giving Milwaukee a 3-1 lead. But St. Louis rallied for three runs in the bottom of the inning and Andújar kept the Brewers off the scoreboard in the seventh. After Bruce Sutter relieved Andújar in the eighth and retired the side in order, the Cardinals scored two more in the bottom of the frame to take a 6-3 lead – and Sutter shut the door to clinch the title.

Andújar finished the World Series with a 2-0 record and 1.35 ERA.

“Give (Andújar) credit: He pitched a nice game,” Brewers first baseman Cecil Cooper told the Associated Press after Game 7. “I would say he threw the ball just as hard as he did (in Game 3).”

The 1983 season was a forgettable one for the Cardinals and Andújar as the team finished 79-83 and Andújar went 6-16. He also continued to make news with his bat that year, hitting .082 (6-for-73) while batting right-handed against wild right handers to protect his arm but batting left-handed against right-handers he considered veterans and bunting right handed against all pitchers.

His numerous quirks were well documented throughout the game.

“It’s great to be alive,” Andújar told the Post-Dispatch, “because when you’re dead, you can’t drink beer.”

In 1984, Andújar and the Cardinals played more like their 1982 form – with Andújar going 20-12 with a 3.34 ERA, leading the NL in wins, shutouts (four) and innings pitched (261.1). He finished fourth in the NL Cy Young Award voting after a season where the Cardinals finished 84-78 while struggling to score runs.

Then in 1985, St. Louis unleashed rookie outfielder Vince Coleman on the league. Andújar – who signed a three-year, $3.45 million contract extension before the season – continued to pitch well and Coleman ran wild on the bases, stealing 110 bags and energizing the team. Andújar went 21-12, tying John Tudor – who finished the season with 20 wins in his last 21 decisions – for the team lead.

But while Tudor got stronger as the season went on, Andújar struggled. He was 15-3 going into a July 12 game against the Padres when San Diego manager Dick Williams, who would skipper the NL in the upcoming All-Star Game, announced that whoever pitched better in that matchup, either Andújar or the Padres’ LaMarr Hoyt – would start the Mid-Summer Classic. Andújar was furious as he believed his record was far superior to Hoyt’s 11-4 mark – and immediately announced that he would not participate in the All-Star Game no matter who started.

“I don’t have a to prove anything to anybody,” Andújar told the Associated Press.

Williams, who made the statement in the hopes of agitating Andújar, won the battle as Hoyt pitched seven shutout innings as the Padres won the July 12 game 2-0. Andújar allowed two runs over eight frames.

Andújar eventually ran his record to 17-4 but lost five of his last six decisions as his workload – and being implicated in the recreational drug use trials going on in Pittsburgh – weighed on him. The Cardinals won the NL East but Andújar struggled in his Game 2 start in the NLCS vs. the Dodgers, allowing six runs in 4.1 innings in an 8-2 loss. He received a no-decision after allowing four runs (two earned) over six innings in Game 6 – a contest the Cardinals won when Jack Clark’s three-run home run in the ninth inning turned a 5-4 Los Angeles advantage into a 7-5 Cardinals win that put St. Louis in the World Series.

But Coleman had been injured during the NLCS after being hit by an automatic tarpaulin machine and was unavailable for the Fall Classic, putting a damper on St. Louis’ running game. The Cardinals won the first two games, however, before the Royals won Game 3 – tagging Andújar with four earned runs over four innings of work.

But St. Louis won Game 4 behind Tudor before Kansas City rallied with wins in Game 5 and 6, the latter coming via a ninth-inning rally that featured a controversial call by umpire Don Denkinger. In Game 7, Herzog turned to Tudor on three days’ rest, skipping Andújar’s turn in the rotation. Tudor allowed five runs over 2.1 innings, and Andújar was eventually called on in relief in the fifth inning as the Royals scored six runs to put the game out of reach.

Andújar permitted an RBI single to Frank White and then walked Jim Sundberg. He did not care for a couple calls from the home plate umpire – Denkinger – and was ejected from the game after bumping the ump.

St. Louis lost 11-0, and Andújar was suspended for the first 10 days of the 1986 season – a penalty that was eventually reduced to five games.

“I know a lot of negative things have been written about him,” Paul Snyder, the Atlanta Braves director of scouting, told United Press International prior to the 1986 season. “But every time I come down here (to San Pedro de Macoris) he’s working with the kids, going from one field to the next. I really admire him because he gives of his time. That’s more than you can say of most players in the states.”

On Dec. 10, the Cardinals traded Andújar to the Athletics in exchange for Tim Conroy and Mike Heath.

“I am going to miss him,” Herzog told the AP about Andújar. “You always figured that when he’s around, something is going to happen.”

Andujar felt the same about Herzog.

“If I would have spent my five-and-a-half years with Houston with Whitey instead, I would have won 20 games seven times,” Andújar told UPI. “He’s the best manager in baseball.”

Andújar went 12-7 for Oakland in 1986 but was limited to just 155.1 innings, his first season since 1981 where he did not work at least 225 frames. He battled injuries in the final season of his contract in 1987, going 3-5 with a 6.08 ERA in 13 starts.

Returning to Houston in 1988, Andújar went 2-5 with a 4.00 ERA as a swingman. After sitting out the 1989 big league season, he pitched in the Senior Professional Baseball Association in the winter of 1988-89 and impressed the Expos, who offered him a contract. But he was released just before Opening Day, ending his big league career.

Andújar returned to the Dominican Republic, where he passed away on Sept. 8, 2015, due to complications from diabetes. Over 13 big league seasons, the pitcher who called himself “One tough Dominican” posted a record of 127-118 with a 3.58 ERA. A four-time All-Star, Andújar finished fourth in the NL Cy Young Award race in both 1984 and 1985.

“He was a joy to manage,” Herzog told the AP upon Andújar’s passing. “When you had Joaquín on your ballclub, you were sitting on a firecracker every day.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

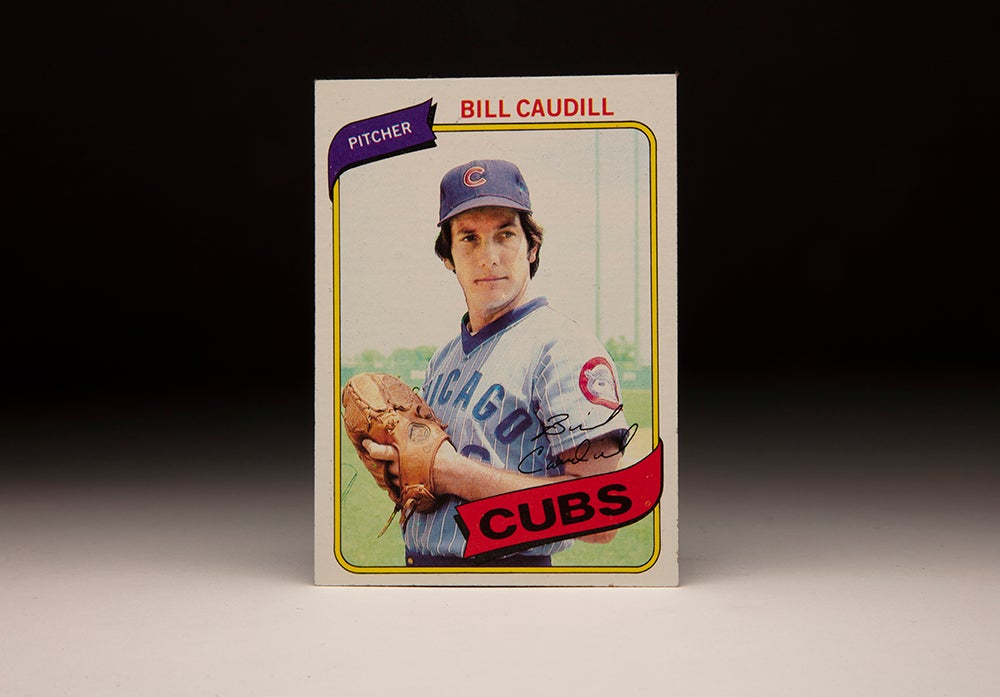

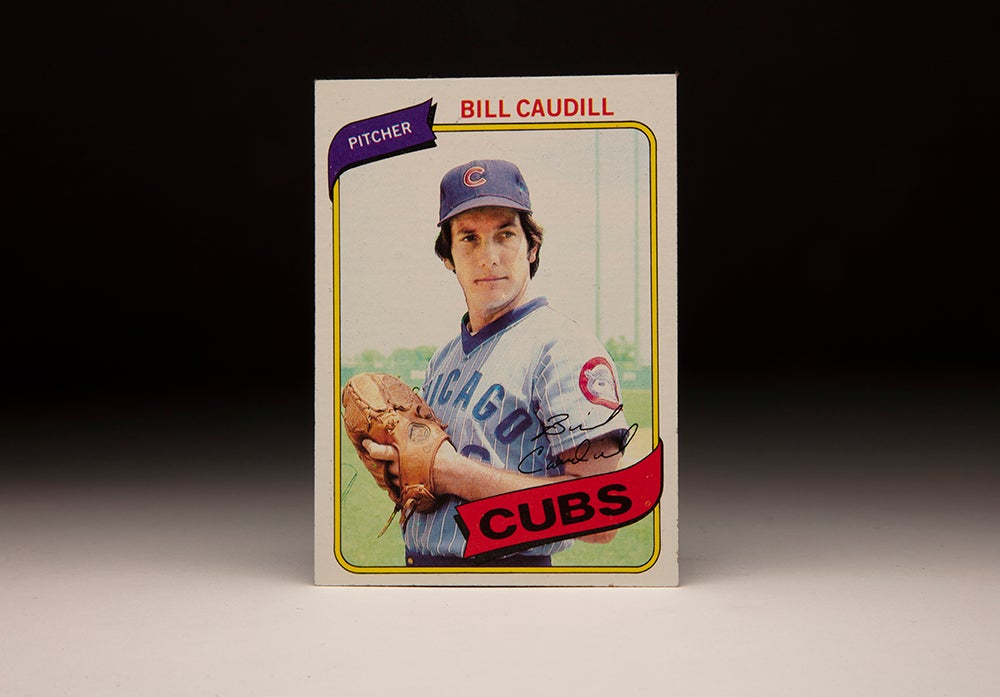

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bill Caudill

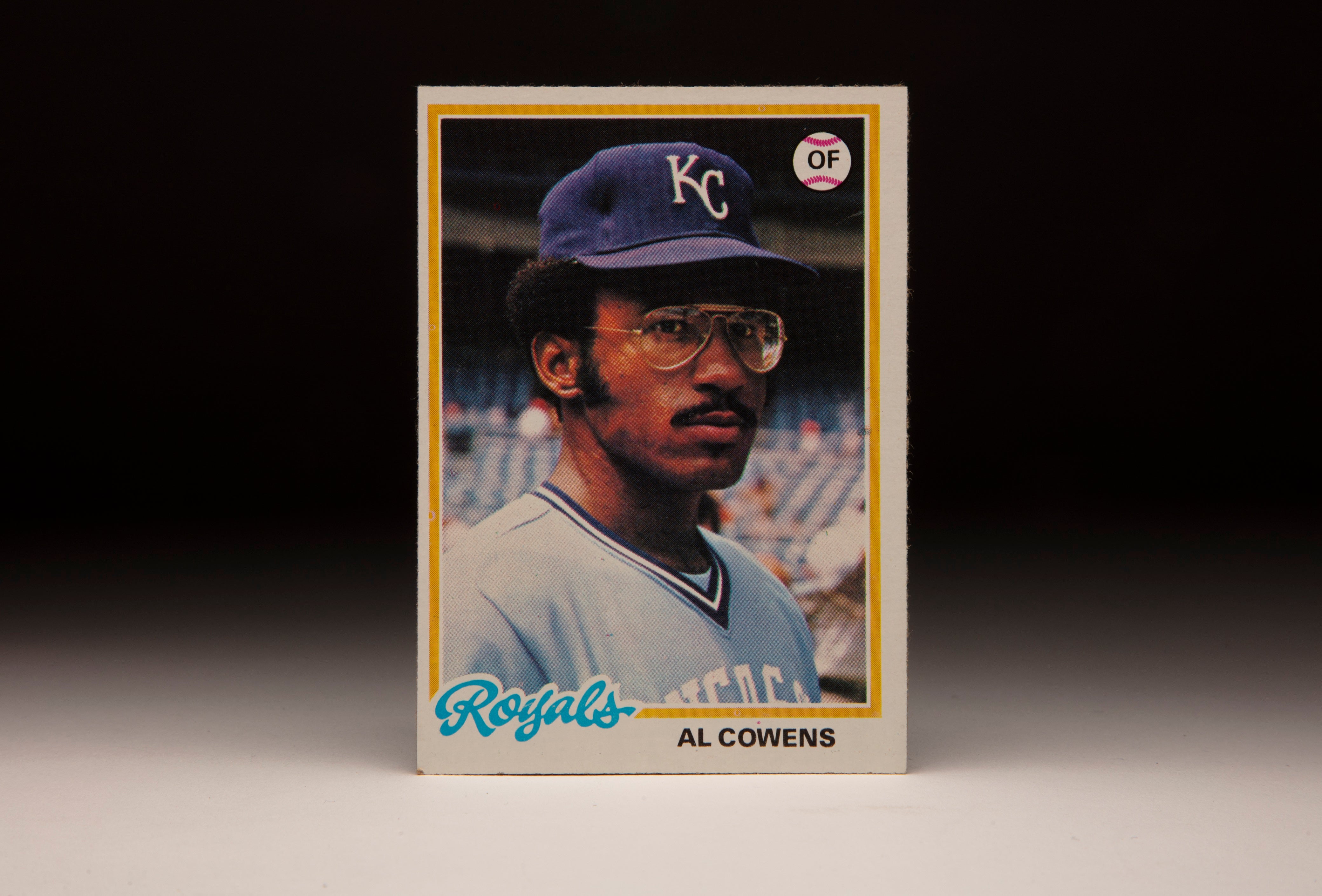

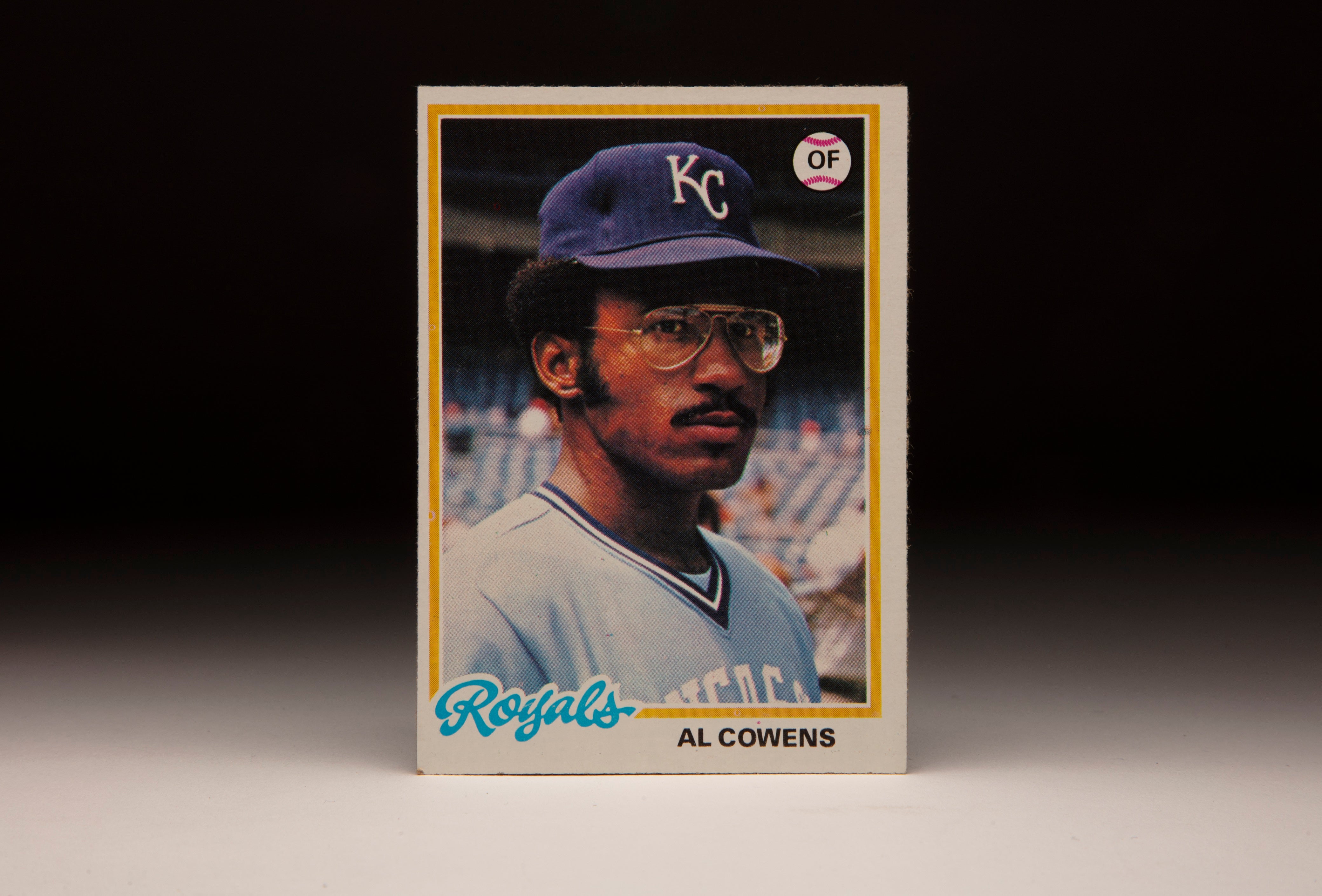

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Al Cowens

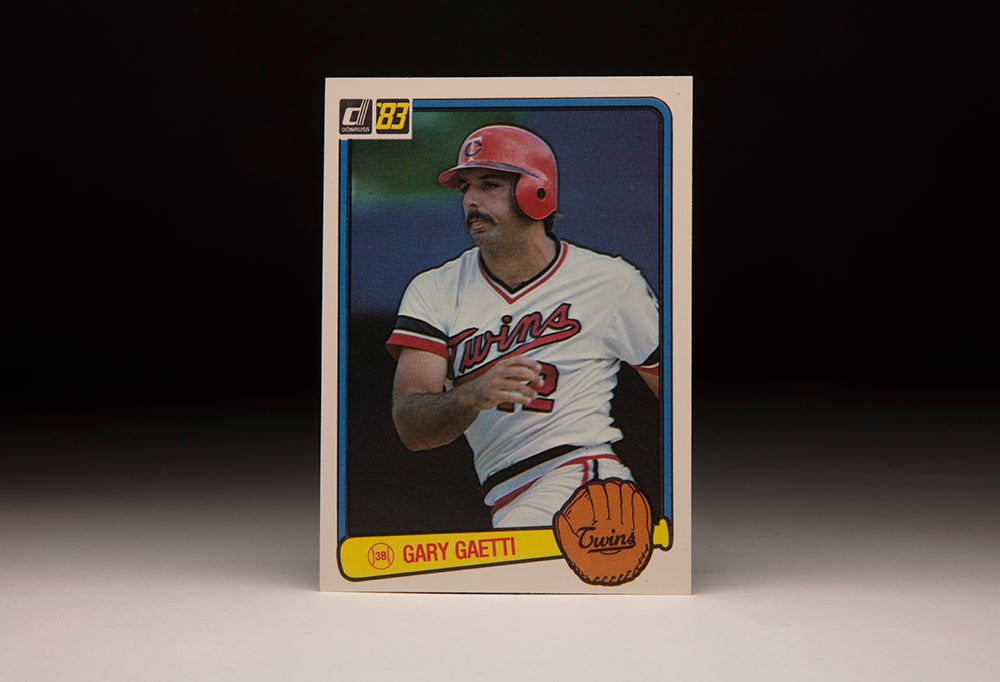

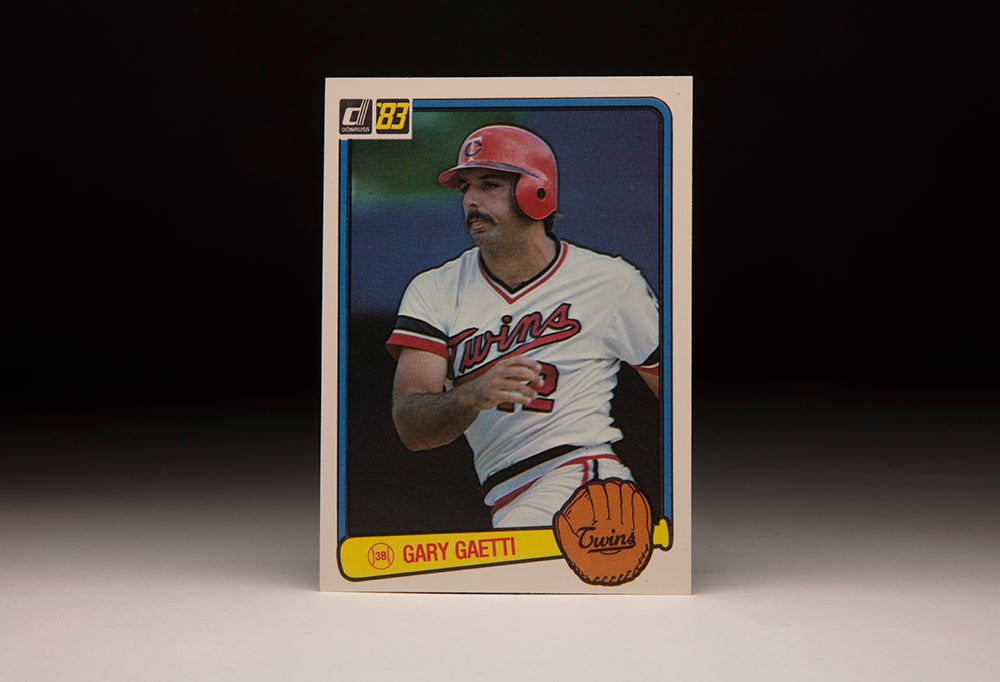

#CardCorner: 1983 Donruss Gary Gaetti

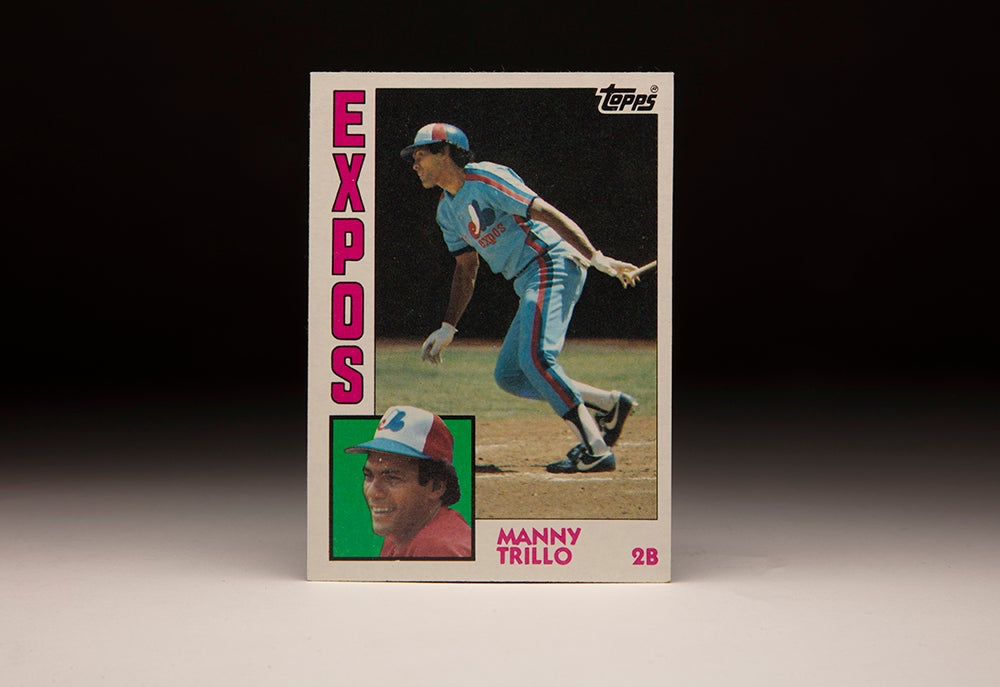

#CardCorner: 1984 Topps Manny Trillo

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bill Caudill

#CardCorner: 1978 Topps Al Cowens

#CardCorner: 1983 Donruss Gary Gaetti