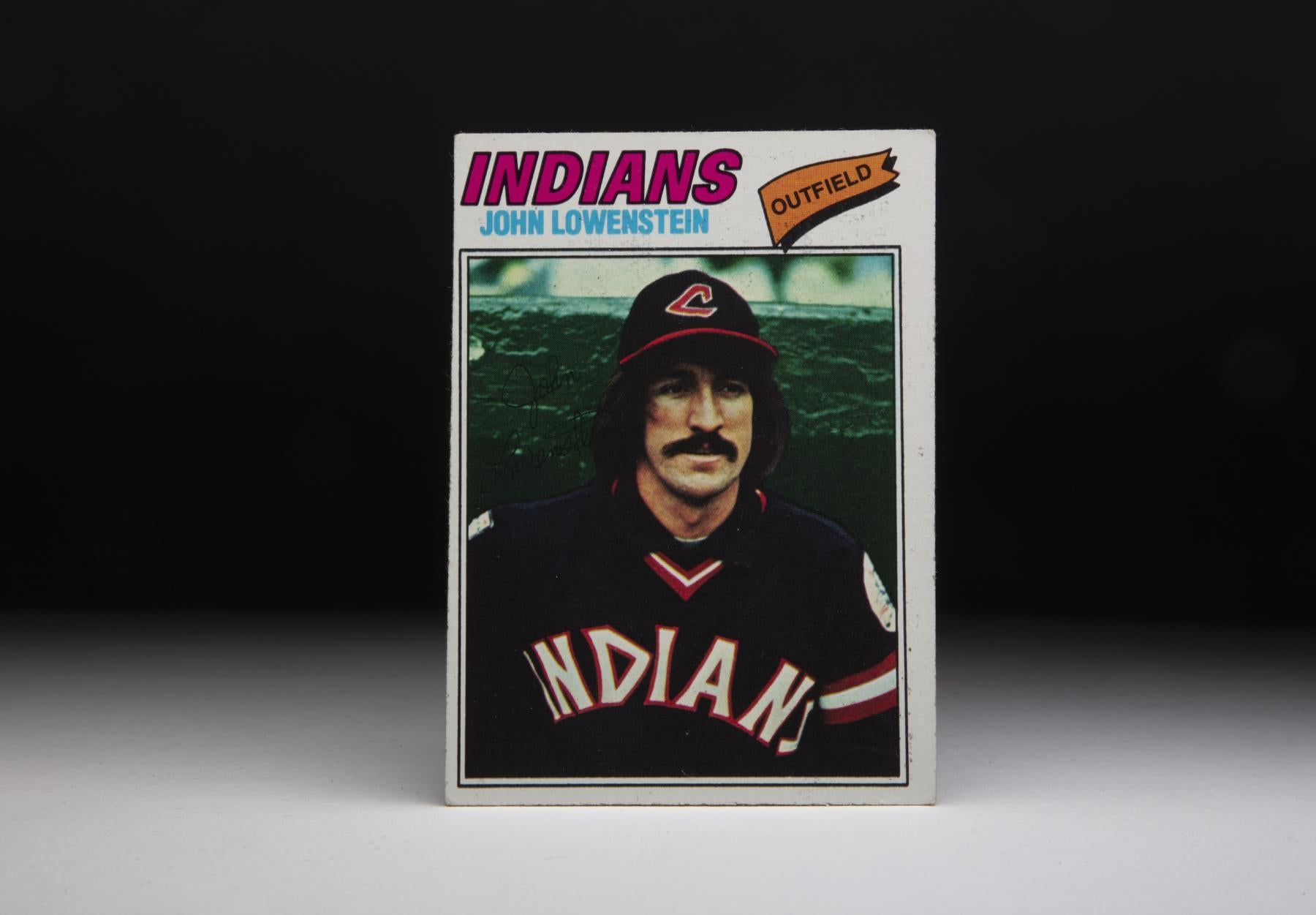

#CardCorner: 1977 Topps John Lowenstein

The all-time leader in virtually every offensive category among players born in Montana – and one of less than three dozen big leaguers native to the Treasure State – John Lowenstein was one of the most popular and quotable players of his generation.

Lowenstein was also a valuable and versatile player on some great and not-so-great teams of the 1970s and 80s.

John Lee Lowenstein was born Jan. 27, 1947, in Wolf Point, Mont., while his father was serving at Glasgow Air Force Base. The Lowensteins moved to Southern California when John was a preschooler and then later to Hawaii and back to California, and John honed his baseball skills in the year-round sunshine of the Inland Empire metro area.

“I’m really more oriented toward California,” Lowenstein told the Great Falls (Mont.) Tribune of his Montana roots. “That’s where I grew up, and that’s where I went to school.”

Playing youth baseball for Babe Ruth League and Legion teams and then at Norte Vista High School, Lowenstein showed enough skill to earn a spot on the University of California-Riverside team. Majoring in anthropology, the lefty-swinging Lowenstein led UC-Riverside to the NCAA College Division World Series in 1968 and was named the shortstop on the small school All-American baseball squad after hitting .393.

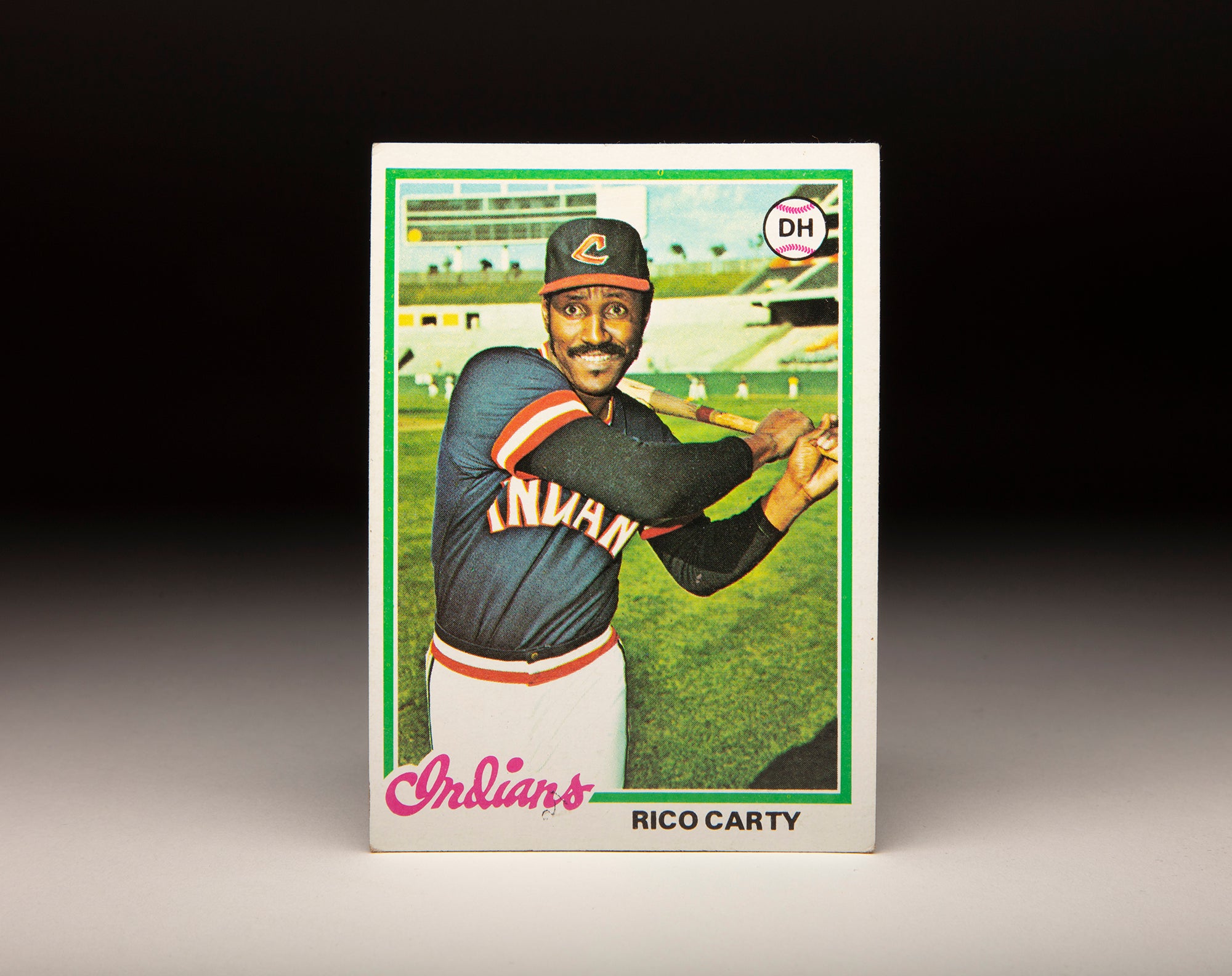

The Cleveland Indians selected Lowenstein in the 18th round of the June 1968 MLB Draft, and Lowenstein quickly signed and reported to Class A Reno of the California League – where he hit .323 in 48 games before earning a late-season promotion to Double-A Waterbury of the Eastern League.

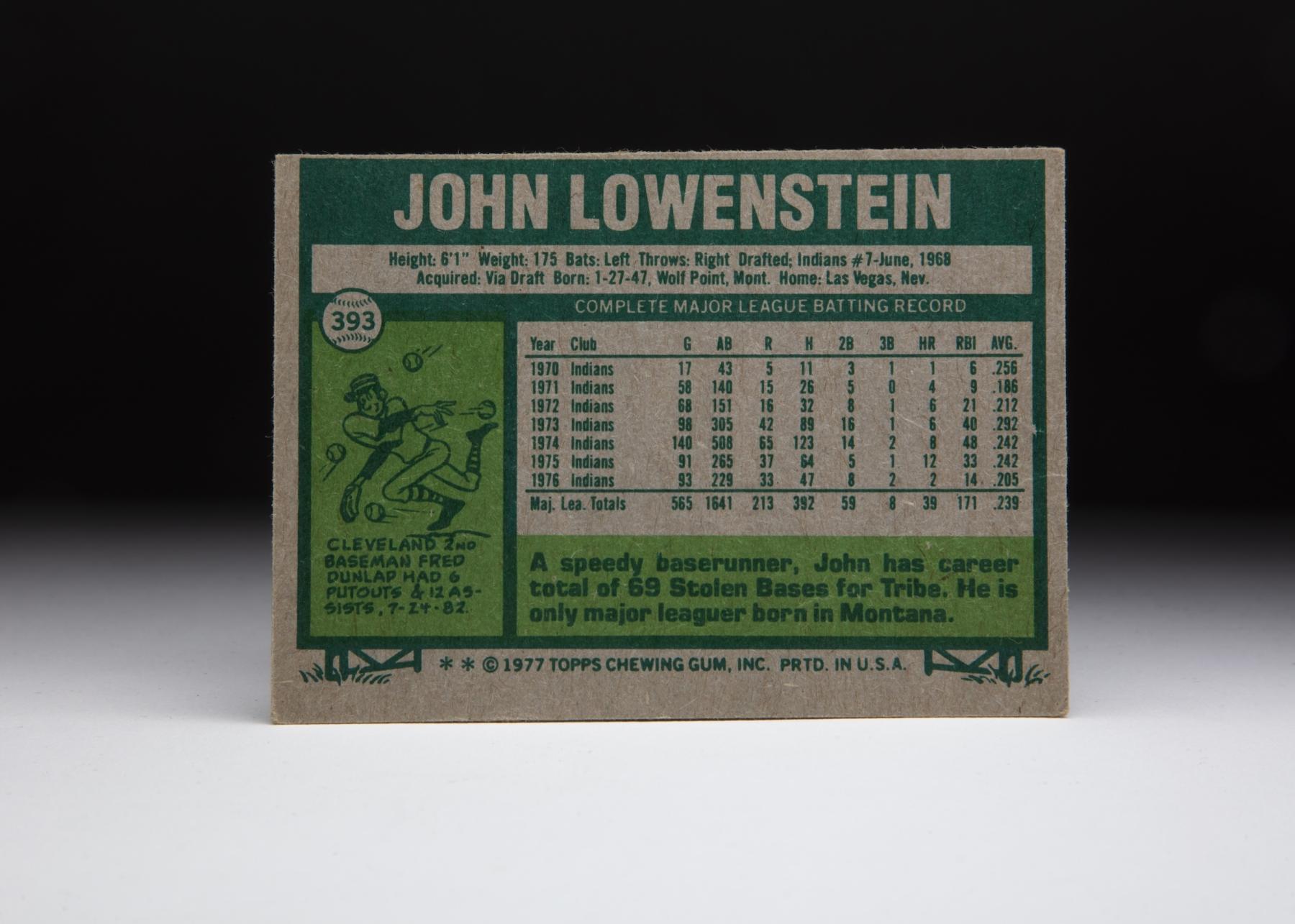

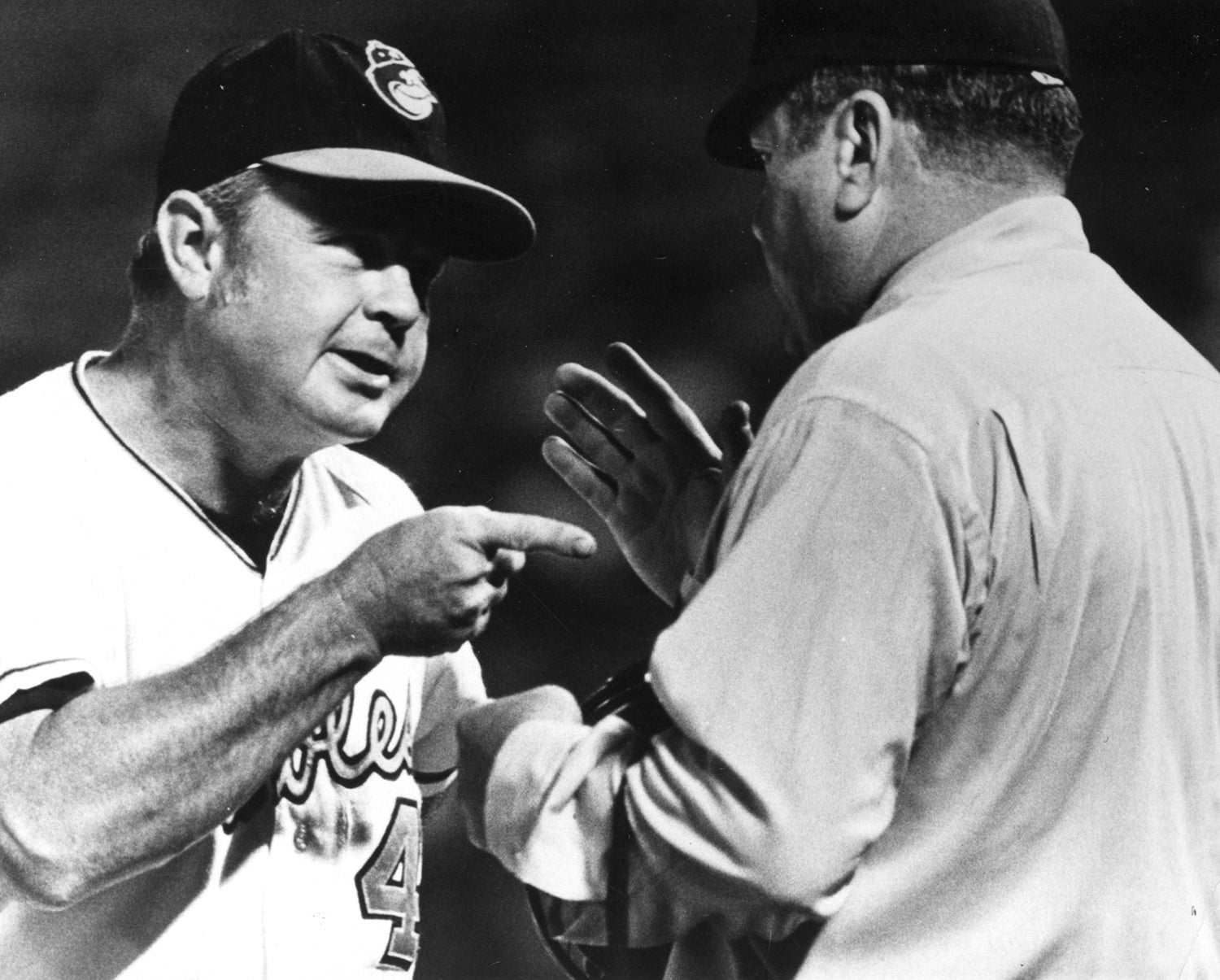

After missing most of the 1969 season while serving in the Marine Reserves, Lowenstein hit .330 with the Indians’ team in the Florida Instructional League and then began the 1970 campaign with Triple-A Wichita. Stationed at third base, Lowenstein hit .295 with 18 homers and a .394 on-base percentage in 108 games for the Aeros before earning a September promotion to Cleveland. In 17 games with the Indians, Lowenstein hit .256.

“I honestly don’t know what we would have done without John,” Wichita manager Ken Aspromonte, who would later manage Lowenstein in Cleveland, told the Wichita Eagle. “He’s played short, third, center and right. He’s hit the ball, made the plays, taken the extra base, everything anyone could ask.”

Lowenstein was named to the first-team American Association squad for his efforts. But the Wichita Eagle, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, took Lowenstein to task for not being very quotable – something that would radically change once Lowenstein reached the big leagues.

“His only interest,” columnist John Swagerty wrote, “was in proving he could play a little baseball. He has taken all the fun out of the game.”

Lowenstein reported to Spring Training with Cleveland in 1971 and quickly impressed manager Alvin Dark with his all-around ability as well as earning the nickname “Mini-Hawk” – a reference to his wardrobe choices that mimicked the flamboyant Ken “Hawk” Harrelson. Lowenstein’s versatility earned him a spot on Cleveland’s Opening Day roster.

“You can come here to Spring Training with all kinds of things in your mind,” Dark told the Associated Press. “But if a guy insists on making you change your mind, you’ve got to let him. And that’s what I’ve got to do now: Let Lowenstein change my mind – or at least keep giving him the opportunity to change it, if he can.”

With his batting average at .185 in mid-May, Lowenstein was sent back to Wichita. But he was recalled in early August after hitting .320 over 37 games when shortstop Jack Heidemann was sidelined with a knee injury. He finished the season batting .186 in 58 games before spending the entire 1972 season with the Indians, now led by Aspromonte. Lowenstein hit .212 in 68 games as a reserve outfielder and reprised that role in 1973, batting .292 in 98 games while playing every position except pitcher, catcher and shortstop.

Aspromonte entered Spring Training in 1974 looking for a permanent spot for Lowenstein.

“He’s too valuable,” Aspromonte told the AP. “I’ve got to find a spot for him in the lineup – someplace.”

Lowenstein, however, recognized that his versatility remained his greatest asset.

“I don’t know from one (day) to the next where I’ll be playing,” Lowenstein said. “You have to devote a lot of time and energy to playing all those positions. It’s not easy playing general maintenance.”

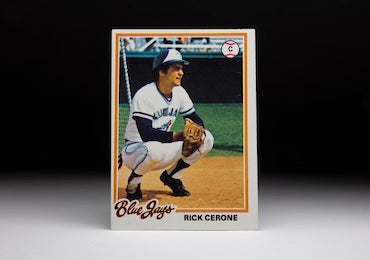

“God, I have to stay up so late to see Mary Hartman,” Lowenstein told the Tampa Bay Times of the difference between the Indians’ Spring Training in Tucson, Ariz., and the Blue Jays’ camp in Dunedin, Fla., referencing the late-night, off-beat soap opera “Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman”.

“That’s the difference between here and Tucson.”

After batting .242 for the third time in four seasons in 1977, Lowenstein was traded again – this time to the Rangers with Tom Buskey in exchange for David Clyde and Willie Horton.

“It’s nice to be with a contending club for a change,” Lowenstein told the Great Falls Tribune at the start of the 1978 season.

He hit .222 with 16 steals and a .363 on-base percentage off the bench during a season where the Rangers won 87 games but finished second in the AL West after being tabbed by many as the division favorites at the start of the campaign.

The Rangers placed Lowenstein on waivers after the season, and the Orioles claimed him for $20,000 on Nov. 27. It would be the start of a seven-year run in Baltimore that would see Lowenstein seemingly get better with age.

Lowenstein started Game 2 in left field and walked and scored in Baltimore’s four-run first inning during what became a 9-8 Orioles win. He had two more plate appearances in Game 3 and another in Game 4 as Baltimore advanced to the World Series. In the Fall Classic against the Pirates, Lowenstein started three games and appeared in three others hitting .231 with three RBI as Pittsburgh won the title in seven games.

In 1980, Lowenstein and right-handed hitting Gary Roenicke again platooned in left field, with Lowenstein receiving more play that usual when Roenicke fractured his left wrist in June. But Lowenstein himself was injured on Jun 19 when – after recording a pinch-hit single off Oakland’s Rick Langford – he was struck in the back of the neck by a throw by Athletics’ first baseman Jeff Newman as he advanced to second on the play. Lowenstein was in obvious pain and a stretcher was called to bring him off the field. But after a few seconds of being carried, Lowenstein bolted upright and thrust his hands in the air triumphantly to the cheering Memorial Stadium crowd.

“I had it planned halfway to the dugout,” Lowenstein told AP. “I had to value the moment because I may never have another chance. The joke would have been on me if I had had a broken neck.”

Lowenstein hit .311 with a .403 on-base percentage in 1980 as the Orioles won 100 games but finished second to the Yankees in the AL East. His average fell to .249 in 1981 but the Orioles were still more than happy with the Lowenstein/Roenicke platoon – a decision that would be rewarded handsomely over the next two seasons.

Age began to catch up with Lowenstein in 1984, however, as he hit .237 in 105 games. Then in 1985, Lowenstein was two for his first 26 when the Orioles decided to make a change. He was released on May 21, ending his career.

“He’s about the only guy I ever saw that the game didn’t get to,” teammate Tippy Martinez said. “I wish I had his attitude.”

Orioles pitching coach Ray Miller was even more effusive of his praise of Lowenstein, who finished his 16-year big league career with a .253 batting average and 881 hits in 1,368 games.

“It’s real nice of him to let me share some of his world,” Miller told the Arizona Republic. “And let me tell you, he’s got a great world. He can just sit and amuse himself by thinking.”

Lowenstein went on call Orioles games on television for a decade. He brought the same humor to the broadcast booth that he did to the field and the clubhouse.

“I’d like to say I’m taking a more businesslike approach to baseball this year,” Lowenstein told the Tampa Bay Times during his brief stay with the Blue Jays in 1977. “But I can’t! That’s not me.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum