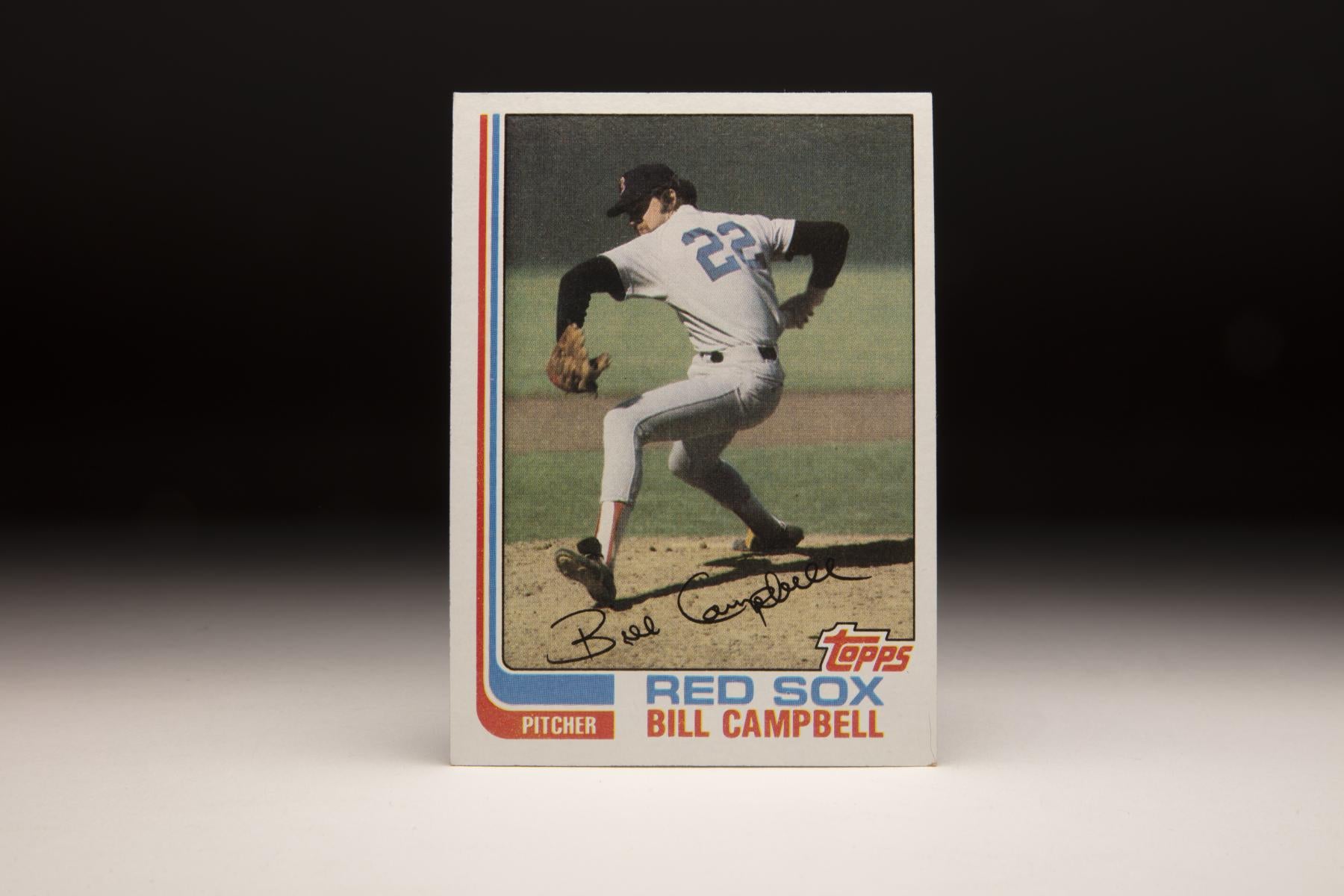

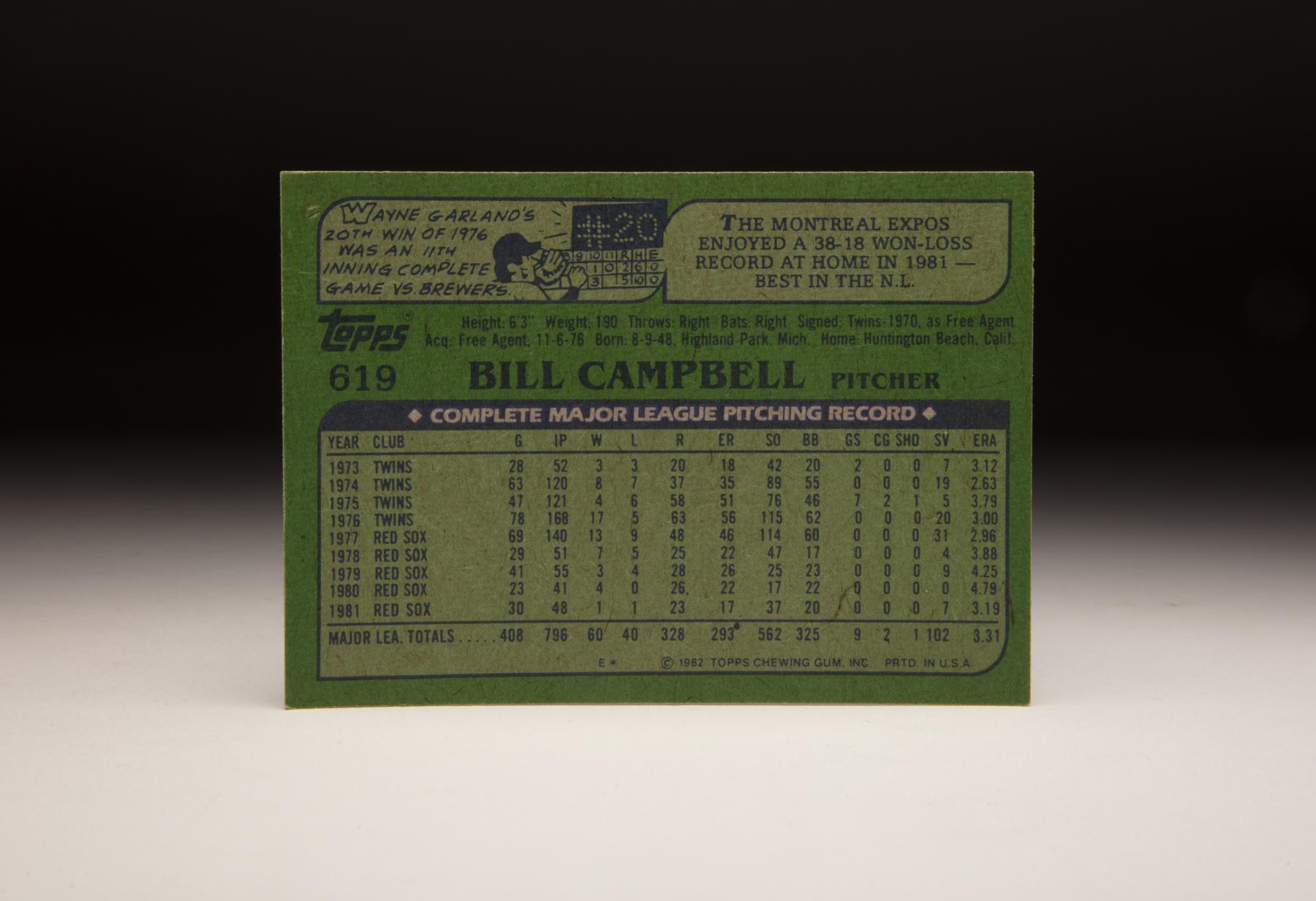

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Bill Campbell

Undrafted out of high school and a veteran of nearly a year of military service in Vietnam, Bill Campbell was an unlikely pioneer in baseball’s free agency era.

But as one of the top relief pitchers of his time, Campbell proved to be one of the most sought after commodities of the first true class of free agents.

Born Aug. 9, 1948, in Highland Park, Mich., Campbell’s family moved regularly during his youth as his father took on different jobs. Eventually landing in Southern California, Campbell fell in love with baseball and played collegiately at Mount San Antonio College, a two-year school. But before he could enroll at a four-year college, Campbell was drafted by the U.S. Army as America ramped up its involvement in the Vietnam War.

Campbell spent almost a year in Vietnam serving as a radio operator near the demilitarized zone.

“Vietnam is something that still lives with me,” Campbell told the Charlotte News in 1972 when he was a minor leaguer in the Twins system. “My best friend was killed just before I got over there and the only way I could attend his funeral was to be a part of the military escort. So I was very patriotic and wanted to go (to Vietnam) to avenge my friend’s death. But when I got there and looked around, I realized (Vietnam) was something different.”

The experience quickly matured Campbell, and when he returned to the United States after his tour he enrolled in college and began playing semipro baseball. Pitching against a Twins rookie team, Campbell authored a no-hitter. On Sept. 25, 1970, the Twins – duly impressed – signed Campbell to a contract and sent him to Wisconsin Rapids of the Class A Midwest League for the 1971 season.

After going 5-3 with a 1.14 ERA over 63 innings in 1971 – missing much of the season due to a separated shoulder – Campbell was promoted to Double-A Charlotte the next season.

“Minnesota said I was going to Class A ball this year and I told them I could pitch in (Double-A),” Campbell told the Charlotte News. “I thought I was in Class A until (Charlotte manager Johnny Goryl) put in a plug for me. (Goryl) made the difference.”

Using a screwball that complimented a sinking fastball, Campbell went 13-10 with a 2.42 ERA in 29 starts for Charlotte, earning the Southern League’s Pitcher of the Year Award.

Promoted to Triple-A Tacoma in 1973, Campbell was named to the Pacific Coast League All-Star Game and had a 10-5 record and 3.65 ERA in 18 starts before the Twins brought him to the big leagues in July. Manager Frank Quilici quickly moved Campbell into high-leverage relief situations, and he finished the year with a 3-3 mark and seven saves in 28 games, working to a 3.14 ERA and striking out 42 batters in 51.2 innings.

In 1974, Quilici made Campbell his closer and Campbell responded with two wins and six saves in the month of April, allowing his first earned run on April 29. The league caught up to Campbell a bit over the next five months but he still finished the season with an 8-7 record, 19 saves and a 2.62 ERA over 63 games.

In Spring Training of 1975, Campbell briefly tested the Twins’ rule against beards, reporting with facial hair and refusing to shave while he consulted union head Marvin Miller. But when Miller informed Campbell he would have to abide by the Twins’ policies, Campbell relented.

Beset by several injuries to their starting rotation, the Twins experimented with Campbell as a starter that season – and Campbell notched his first and only career shutout against the Rangers on July 4. But even in the wake of that success, Campbell was ready to head back to the bullpen.

“I think I can do the club more good as a relief pitcher,” Campbell told the Minneapolis Star Tribune. “I have the arm to pitch three or four times a week.”

In 47 appearances in 1975, including seven starts, Campbell went 4-6 with five saves and a 3.79 ERA. Then in 1976, new Minnesota manager Gene Mauch – who had experienced the value of strong bullpen arms with Mike Marshall in Montreal – made Campbell his closer.

Campbell thrived under the heavy workload, going 17-5 with 20 saves and a 3.01 ERA in an American League-best 78 games while finishing seventh in the AL Cy Young Award voting and eighth in the league MVP race.

Campbell remains the only pitcher in history with at least 17 wins and 20 saves in one season.

Campbell’s gamble paid off. By not signing his 1976 contract, Campbell became eligible for the first free agent re-entry draft and was selected by 12 teams, including the Red Sox. With the help of pioneering agent LaRue Harcourt, Campbell signed a five-year deal worth $1 million with Boston on Nov. 6, 1976. He had balked at signing his 1976 deal with the Twins after Griffith stood firm on his offer of $23,000, about $7,000 less than Campbell requested.

“Now I’m financially secure and won’t have to be concerned with contracts for a long while,” Campbell told the Associated Press. “I have to go out shopping right away. I have to get a birthday gift for my wife.”

Campbell became the first of the new class of free agents to announce signing with a new club, agreeing to a deal less than 48 hours after the Red Sox selected him the re-entry draft. Among modern era free agents, only Messersmith signed a contract before Campbell.

Campbell struggled in his first few appearances with the Red Sox in 1977, allowing nine earned runs in his first five games while racking up three losses. But he picked up his first save on April 26 against the Brewers, notched his first win five days later with three shutout innings against the A’s and went back to his workhorse ways of 1976 for the rest of the season.

In June, Campbell recorded eight saves and a win in a 22-day span before notching nine saves and a victory in 11 games in September. He finished the year with a 13-9 record, 31 saves and a 2.96 ERA in 140 innings over 69 games – marking the fourth straight season he pitched at least 120 innings.

“I’ve learned this year that you’ve got to keep going,” Campbell told the AP. “Early in the season I’d come in with the lead and I’d get lackadaisical. Now I go in and I really concentrate, pitching as if I always have a one or two-run lead.”

Campbell’s arm, weighed down by years of throwing the screwball, would not be right for a while. He appeared in 41 games in 1979, going 3-4 with nine saves and a 4.28 ERA. Then in 1980, Red Sox team physician Dr. Arthur Pappas diagnosed the problem as a weakened supraspinatus muscle in his shoulder, located around the rotator cuff. Campbell rehabilitated at Boston’s Children’s Hospital Medical Center and did not appear in a game until late June.

In 23 games in 1980, Campbell was 4-0 but with a 4.79 ERA and no saves. But he rebounded in 1981 to go 1-1 with seven saves and a 3.17 ERA in 30 games in that strike-shortened season, proving to teams – as his contract with the Red Sox expired – that he was healthy again.

On Dec. 8, 1981, new Cubs general manager Dallas Green signed Campbell to a three-year, $1.2 million deal that would bring the reliever to Chicago.

“Based on his past, it’s obvious he's capable of saving us a lot of games,” Green told United Press International. “The arm injuries that have cropped up in recent seasons have disappeared and at the end of last season the Cubs’ scouting staff felt Bill was throwing as good as they’ve ever seen him throw.”

When the Phillies would not consider Buckner’s contract demands, however, the trade was revised. It turned out to be a win for the Cubs, as Dernier and Matthews helped lead Chicago to the NL East title that year. But Campbell pitched effectively for Philadelphia, going 6-5 with a save and a 3.43 ERA as a setup man for closer Al Holland.

On April 6, 1985, the Phillies – in what as perceived as a salary move to clear Campbell’s $400,000 salary from their books – traded Campbell and Iván DeJesus to the Cardinals in exchange for pitcher Dave Rucker.

“We hope he does the job in the bullpen that he’s done with various clubs,” Cardinals general manager Dal Maxvill told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about Campbell following the trade.

Maxvill was building a relief staff that would be known as a “bullpen by committee” as the Cardinals tried to replace future Hall of Famer Bruce Sutter, who left for Atlanta following the 1984 season. Deftly handled by manager Whitey Herzog, the group of Jeff Lahti, Ricky Horton, Ken Daley and Campbell helped the Cardinals close down games for most of the year until fireballing rookie Todd Worrell debuted in late August.

Campbell finished the season with a 5-3 record and four saves in 50 appearances, posting a 3.50 ERA.

Pitching in the postseason for the first time, Campbell worked 2.1 scoreless innings over three games in the NLCS vs. the Dodgers as St. Louis advanced to the World Series. In the Fall Classic, Campbell’s first two outings were scoreless before he allowed one run in 1.2 innings in the Game 7 finale against the Royals – failing to squash a Kansas City rally in the third inning after starter John Tudor faltered.

In six postseason games that October, the 37-year-old Campbell allowed just one run.

A free agent again following the season, Campbell signed with the Tigers and manager Sparky Anderson penciled him into a setup role. But a balky elbow limited to Campbell to just 34 games, during which he posted a 3-6 record with a 3.88 ERA.

Released by the Tigers following the season, Campbell signed with the Expos during Spring Training of 1987.

“He’s an experienced guy,” Expos general manager Murray Cook told the Montreal Gazette. “He doesn’t have great stuff anymore but he continues to put pretty good numbers on the board.”

But after allowing nine earned runs over seven appearances, Campbell was released on May 1. He would later pitch in the Senior Professional Baseball Association but would never appear in a big league game again.

Later, Campbell would claim his former agent, LaRue Harcourt, lost hundreds of thousands of dollars Campbell had earned due to tax shelter schemes that went bad.

Campbell would go on to serve as a longtime coach in the Brewers organization and was the club’s big league pitching coach in 1999. He passed away on Jan. 6, 2023, having visited the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown for the first time only a few months before.

In exactly 700 big league games, Campbell was 83-68 with 126 saves and a 3.54 ERA. For a player who took an unconventional path to the majors – and who never expected to have a long career – it was truly a remarkable record.

“I’ve come to a realization,” Campbell told the AP in 1977, “that a guy like me is only in the game for five years or so.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum