“As captain, I had to employ all me rhetoric to induce attendance, and often thought it was useless to continue the effort, but my love for the game, and the happy hours spent at the ‘Elysian Fields’ led me to persevere.”

- Home

- Our Stories

- Doc Adams helped shape baseball’s earliest days

Doc Adams helped shape baseball’s earliest days

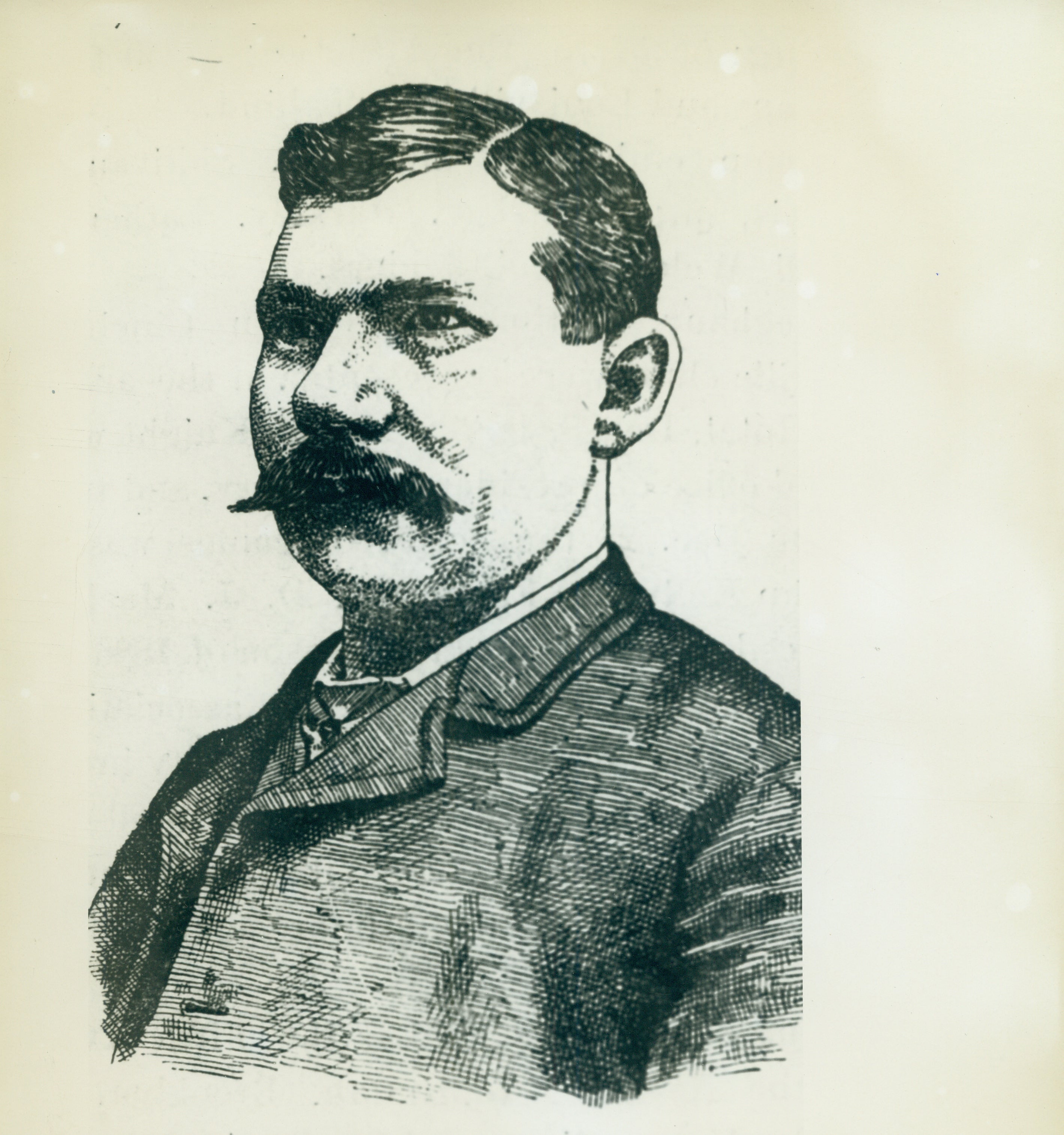

In the mid-19th century, Doc Adams was first introduced to “base ball,” a sporting activity with rules and regulations that varied from team to team. A few decades later, this figure from the game’s nascent years would be called by many the “Father of Baseball” due to his important contributions in turning the sport into the National Pastime.

Adams, a talented ballplayer who became a pioneering force on a multitude of fronts in baseball’s early years, is one of 10 finalists on this year’s Pre-Integration Committee ballot at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The Pre-Integration Committee will vote on Dec. 7 at baseball’s Winter Meetings in Nashville, Tenn..

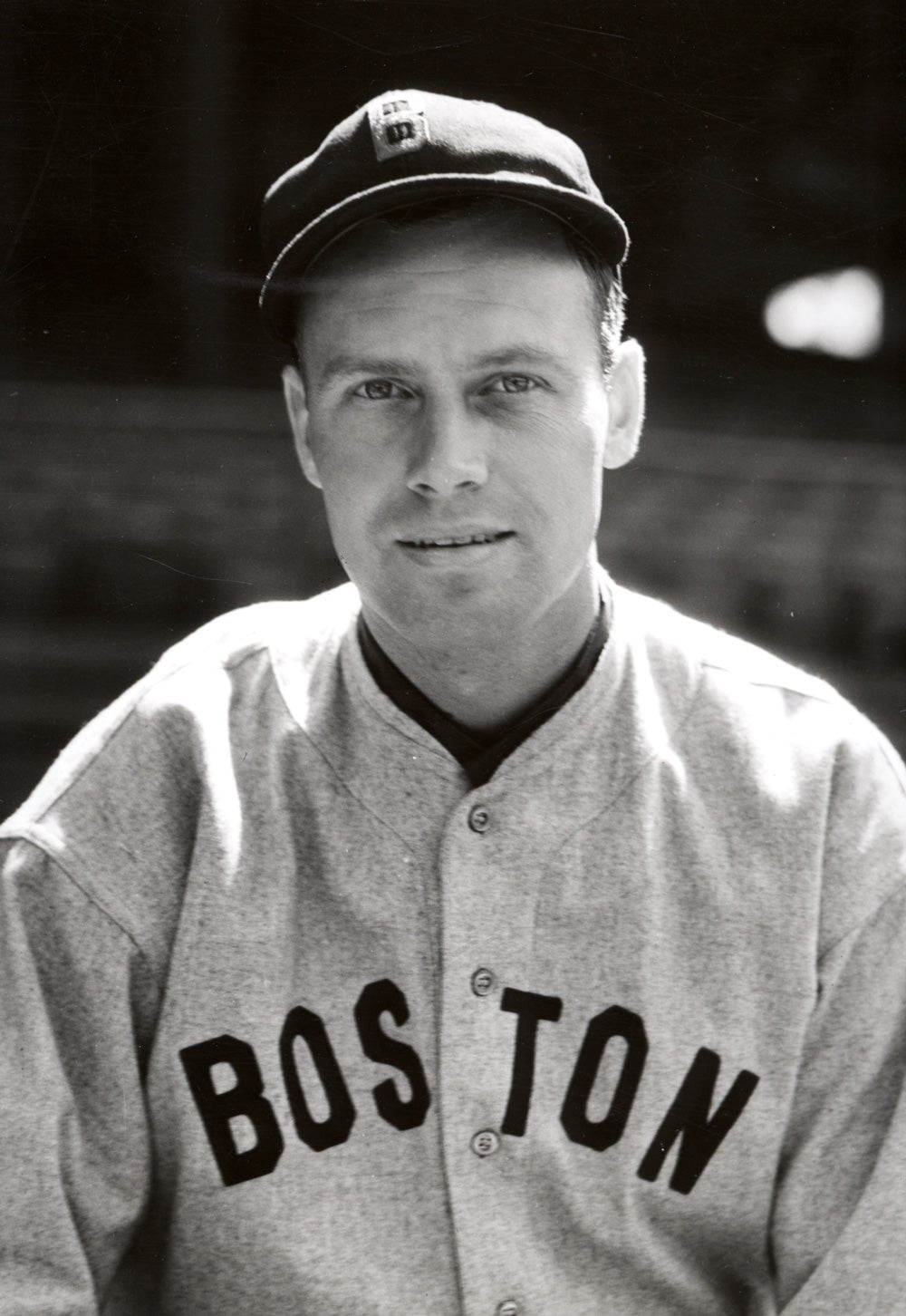

The 10 candidates on the Pre-Integration Committee ballot are: Sam Breadon, Bill Dahlen, Wes Ferrell, August (Garry) Herrmann, Marty Marion, Frank McCormick, Harry Stovey, Chris von der Ahe, Bucky Walters and Adams. Any candidate who receives at least 75 percent of all ballots cast will be enshrined in the Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2016.

Born Nov. 1, 1814, in Mont Vernon, N.H., Adams graduated from Yale College in 1835, then attended Harvard Medical School, from where he acquired a degree in 1838. By the next year he was in New York City establishing his own general practice. But it wasn’t long before Adams, some two decades before the start of the Civil War, was among the young professionals giving “base ball” a chance in this urban setting.

Adams, who joined the New York Base Ball Club in 1840, became a member of the famed Knickerbocker Base Ball Club in 1845, a few weeks after the club was formed. He would eventually play all positions, except pitcher, during his years with the club. Adams was elected president of the club in 1846, a position he held for the next three years and again from 1856 to 1858.

“In September 1845 some young men formed the Knickerbocker base ball club. They went into it just for exercise and enjoyment, and I think used to get a good deal more solid fun of it than the players in the big games do nowadays,” said Adams in an 1895 interview. “About a month after the organization of this club, several of us medical fellows joined in. The following year I was made president, and served as long as I was willing to retain the office.”

The Knickerbockers, the most organized and influential of the baseball clubs during this period, were led in their formative years by Adams. Under his presidency, the Knickerbockers became the model for all other clubs of the time.

“Our players were not very enthusiastic at first, and did not always turn out on practice days. There was then no rivalry, as no other club was formed until 1850, and during those five years base ball had a desperate struggle for existence,” said Adams. “As captain, I had to employ all me rhetoric to induce attendance, and often thought it was useless to continue the effort, but my love for the game, and the happy hours spent at the ‘Elysian Fields’ led me to persevere.”

Prior to the mass production of baseball equipment, Adams helped standardize the game’s tools and learned how to make balls and bats for the Knickerbockers and later for other clubs.

“We had a great deal of trouble in getting balls made, and for six or seven years I made all the balls myself, and not only for our own club, but also for other clubs when they were organized,” Adams said. “I went all over New York to find someone who would undertake this work, but no one could be induced to try it for love or money.

“It was equally difficult to get good bats made, for no one knew anymore about making bats than balls. The bats had to be turned under my personal supervision, the workman stopping occasionally for me to ascertain when the right diameter and taper was secured.”

It was during the time between 1849 and 1850 that historians give Adams credit as the first to position himself as a short-fielder, which eventually became the shortstop position. He pioneered this innovative maneuver in order to relay throws from the outfield.

In 1856, Adams was a leading proponent in holding a convention of all baseball clubs to formalize rules.

“At the close of 1856 there were 12 clubs in existence, and it was decided to hold a convention of delegates from all of these for the purpose of establishing a permanent code of rules by which all should be governed … the result was the assembling of the first convention of base ball players in May 1857. I was elected presiding officer,” Adams said. “In March of the next year the second convention was held, and at this meeting the annual convention was declared a permanent organization, and with the requisite constitution and bylaws became the National Association of Base Ball Players.”

As a leading figure in these formative times, Adams played an important part in the evolution of the sport. In helping to establish such recognizable aspects of the game as having nine players per team, the nine-inning game, 90 feet between bases, and catching the ball on the fly rather than being able to catch the ball on a bounce for an out, he can lay claim as an important early figure.

“I was the chairman of the Committee on Rules and Regulations from the start and so long as I retained membership. I presented the first draft of rules, prepared after much careful study of the matter, and it was in the main adopted. The distance between bases I fixed at 30 yards,” Adams said. “In every meeting of the National Association while a member I advocated the ‘fly-game’ – that is, not to allow first-bound catches – but I was always defeated on the vote. The change was made, however, soon after I left, as I predicted in my last speech on the subject before the convention.

“The distance from home to pitcher’s base I made 45 feet,” he added. “I resigned in 1862, but not before thousands were present to witness matches, and any number of outside players standing ready to take a hand on regular playing days. But we pioneers never expected the game to be universal as it had now become.”

When Adams resigned from the Knickerbockers in 1862, he was awarded honorary membership and presented him with a scroll that proclaimed him “Nestor of Ball Players.” After leaving his medical practice, Adams relocated to Ridgefield, Conn., where he was the first president of the local bank and served in the state’s House of Representatives.

After Adams passed away at the age of 84 on Jan. 3, 1899, in New Haven, Conn., the New York Tribune’s obituary read, in part, “took the keenest pleasure in athletic sports, and soon after coming to New York became one of the earliest members of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, the first organization of its kind in existence. He became president of the club, and took the most active interest in its welfare and in the development of the game, even giving his personal attention to making bats and balls, articles then unknown to manufacturers, and retaining his position as an authority on all matters pertaining to the sport until he left New York.”

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

2016 Pre-Integration Committee Ballot

Bill Dahlen stands test of time

Ferrell remembered for pitching, hitting skill

Gary Herrmann - A King in Queen City

Marty Marion - No shortage of talent

Reds slugger Frank McCormick

19th century star Harry Stovey

Chris von der Ahe - A Magnate for Success

Bucky Walters - Making his pitch

2016 Pre-Integration Committee Candidates

Hall of Fame Weekend

Support the Hall of Fame

Related Stories

King John Schuerholz

Chris von der Ahe - A Magnate for Success

Astrodome barely contains Mike Schmidt’s blast

Doc Adams helped shape baseball’s earliest days

1953 Hall of Fame Game

Tigers trade John Smoltz to Braves

Carew had season for the ages in 1977

Bucky Walters - Making his pitch

Writers Elect Four to the Hall for the First Time in 60 Years

01.01.2023

Hall of Fame Celebrates World Series Weekend, Honoring Kansas City Royals, July 2-3 in Cooperstown

01.01.2023

JOHN SCHUERHOLZ, BUD SELIG ELECTED TO NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME BY TODAY’S GAME ERA COMMITTEE

01.01.2023