- Home

- Our Stories

- Lou Brock traded to Cardinals

Lou Brock traded to Cardinals

The perspective history affords can be daunting.

“Thank you, thank you, oh, you lovely St. Louis Cardinals. Nice doing business with you. Please call again any time.”

Such were the words of Chicago Daily News sportswriter Bob Smith, penned on June 16, 1964. The source of Smith’s gratitude? The day before, the Cardinals had dealt one of the top pitchers in the National League, Ernie Broglio, to the Cubs. Broglio had gone 18-8 the year before, and had led the NL with 21 victories a few years before that. It was a six-player deal and all it cost the Cubs was Brock, who would turn 25 years old three days after the trade.

Little did Smith – or anybody else – know the “business” Smith was so gleeful about would soon be one of the most infamous trades of the 20th century.

“They wanted to run our GM Bing Devine out of town at first,” Cardinals star Mike Shannon told the Chicago Tribune. “But as players, we knew the possibility of Lou.”

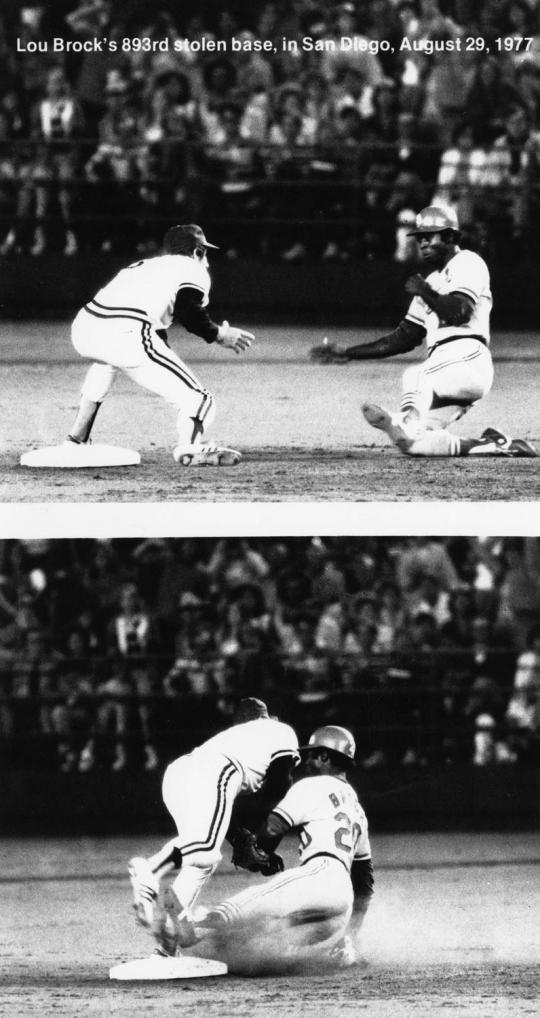

At the time, no one – not even Devine — truly knew the possibility of Lou. A .251 hitter at the time of the trade, he would hit .348 with 33 stolen bases for the Cardinals the rest of that season. But that 1964 campaign was just a precursor to a historic career – going on to join the 3,000-hit club and become the greatest base-stealer, with a then-record total of 938 thefts, in baseball history.

Broglio, hampered by injury, would win a total of seven more games before retiring after 1966 season.

But the Lou Brock whose star is imprinted in the St. Louis Walk of Fame is not the same Lou Brock who started his big-league career at Wrigley Field on Sept. 10, 1961. For him, the game-changer was team dynamics. The Cubs’ managerial system of rotating coaches sent the young center fielder mixed messages, and gave him little room for growth.

“It was like being in a prison yard with everyone waiting for you to do something wrong,” Brock told the Chicago Tribune. “There was the thrill, yes, of coming to the major leagues – but I was scared to death…No one even showed me how to flip the sunglasses, or when to do it. There I was, alone, learning on my own.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

As a fresh-faced ballplayer out of Southern University with only one full season of minor league experience, the experimental system in Chicago was a poor introduction to the major leagues. So the stark difference he encountered in St. Louis sparked a wave of change that he would ride through until the end of his 19-year career.

On his first full day as a Cardinal, Manager Johnny Keane brought Brock to left field, and told him that “It’s a big one and it’s all yours. If you can do what I think you can, you ought to be able to play out here the rest of your life.”

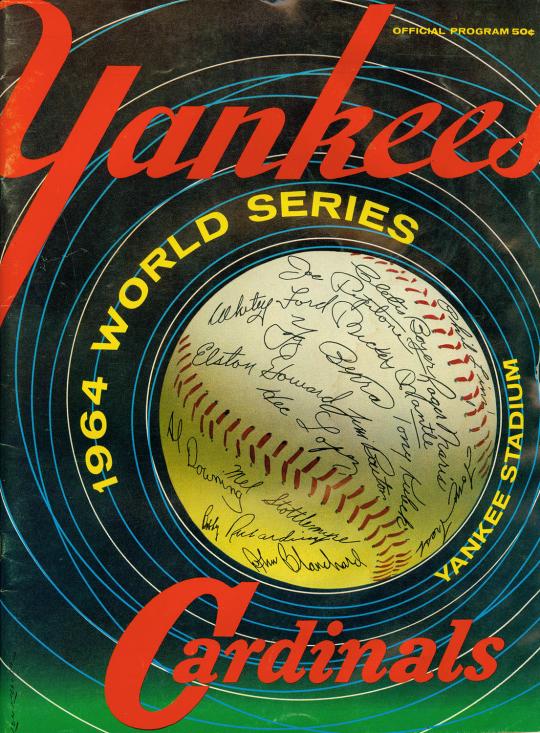

He took Keane’s vote of confidence and ran with it, lifting his 28-31 team from eighth place in the National League to winning the 1964 World Series. His relationship with the Cardinals was a reciprocal one – as he got better, they got better – an achievement that, looking back, Brock sees as the highlight of his historic career.

Days after being inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1985, he spoke with reporters about what he saw as his legacy. He told them that stolen-bases and hits aside, he strongly felt that it was the “ability to light the fuse to enthusiasm, to cause teams and myself to play to the limits of their ability. That gives you a purpose for being there. You become a chemist which makes a team tick. I think I had that ability.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Mentioned Hall of Famers

Related Stories

Pick a Pair: Hall of Fame Class of 2016 makes draft history

Umpires Break Through Glass Ceiling

Bob Gibson wills Cardinals to Game 7 victory in 1964 World Series

Library research a hallmark of Museum’s mission

Judy Johnson elected to the Hall of Fame

1986 Hall of Fame Game

Writers Elect Four to the Hall for the First Time in 60 Years

Baseball Road Show

01.01.2023

Hall of Famers PLAY Ball in Cooperstown in Support of Museum’s Education Programs

01.01.2023

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Remembers Yogi Berra

01.01.2023