Age is a question of mind over matter. If you don't mind, it doesn't matter.

- Home

- Our Stories

- Satch's Swan Song

Satch's Swan Song

Aging legend came back for one historic night in the big leagues

Much of the infectious allure of Leroy “Satchel” Paige lies in the mystery: Was it real or was it a myth?

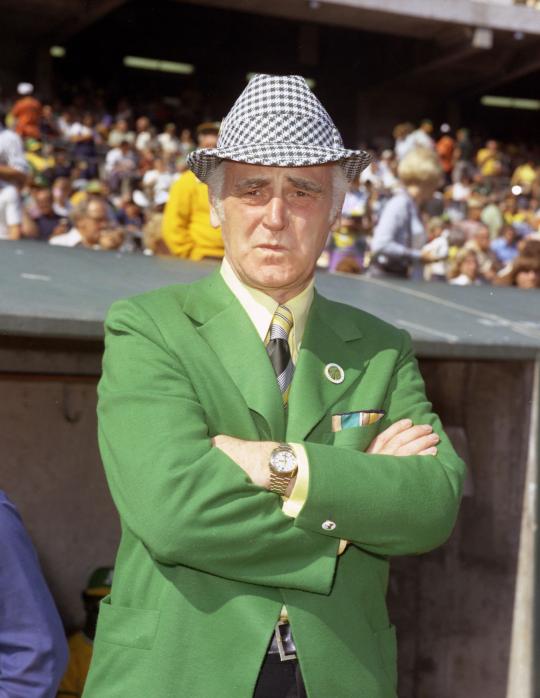

Some of that mystery is based in the numbers. Paige himself claimed to have pitched around 2,500 games in his life, with at least 50 no-hitters, and estimated that around 10 million people saw him play. The numbers seem inconceivable until one recalls that Paige pitched for more than 40 years – often year-round.

The other mysteries are evoked from the stories. Did he really have his infielders sit down before striking out batters? (Yes.) Did he really intentionally load the bases in the 1942 Negro League World Series to strike out Josh Gibson on three pitches? (According to accounts, yes.) Was his stuff – the bee-ball, jump ball, two-hump blooper and that incredible fastball – really that good? (According to numerous Hall of Famers including Joe DiMaggio, Dizzy Dean and Bob Feller, yes.)

By the evening of Sept. 25, 1965, all of these legends from Satchel’s past in the Negro Leagues, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, the major leagues and everywhere in between had been well established and distributed.

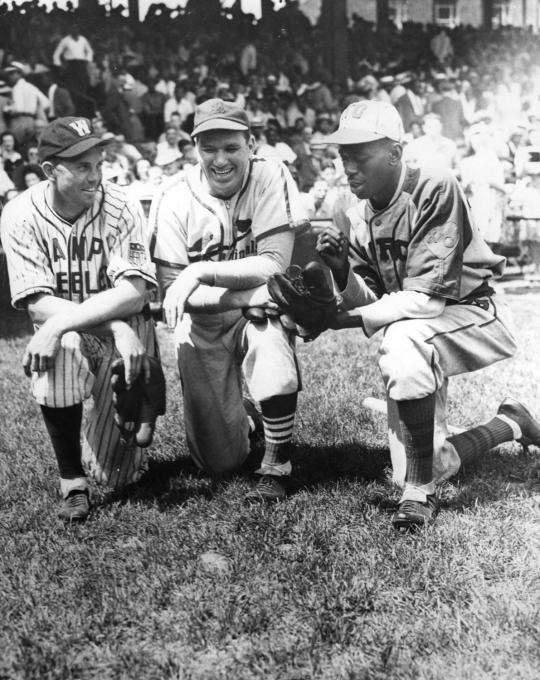

So what a thrill it must have been for the 9,289 fans at Kansas City Municipal Stadium to see the 59-year-old Satchel Paige written down as the home team’s starting pitcher that evening. It was one last chance, or so maybe it seemed, to add another mythical story to the legend.

Looking For Another Chance

More than a decade had passed since Paige had proved to the world that he could pitch in the major leagues, helping Cleveland win the 1948 World Series and earning All-Star selections in his late 40s in 1952-53. But Ol’ Satch did not slow down after the Browns released him in early 1954. In fact, his first assignment after the major leagues was playing basketball with Abe Saperstein’s Harlem Globetrotters. A quick stop in the Carolina League followed before Paige’s old friend Bill Veeck signed him to pitch with the Triple-A Miami Marlins from 1956-58. Paige also had a stint with the Cardinals’ Triple A affiliate in Portland at age 54.

Paige’s desire to return to the major leagues was undoubtedly founded on pride, but it was also financially based, as he was seeking to complete five years of big league service time to qualify for a player’s pension. Veeck was unable to convince his White Sox staff to take him in, but the old pitcher found a home with another lively owner: The Athletics’ Charlie Finley.

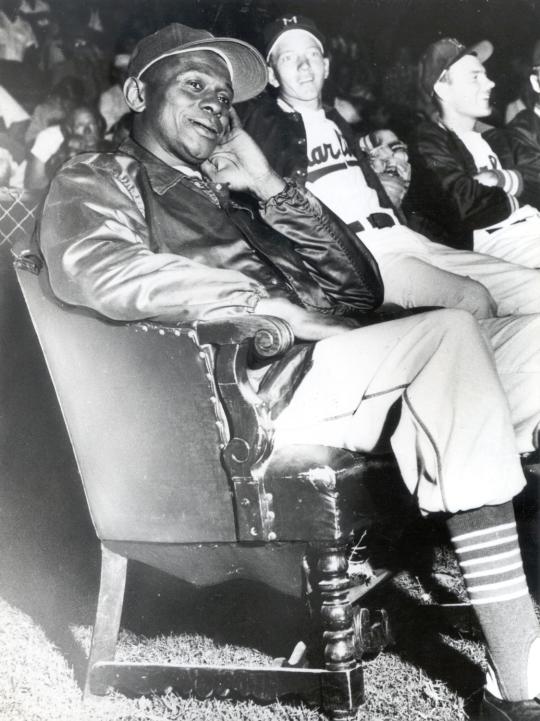

Mired in last place, Finley’s club was in the midst of a lost season. The A’s were 40 games back and not even Finley’s antics – which included bringing a live mule into the press box – could bring in fans. Finley devised one last gimmick and called it “Satchel Paige Appreciation Night.” But this would not be a run-of-the-mill old timer’s celebration: No bobbleheads, truck rides or ceremonial first pitch. Paige was going to start the game on the mound against the Red Sox. At age 59 years, 2 months and 18 days, he would become the oldest player in major league history, surpassing infielder Charley O’Leary (age 58).

“I thought they were kidding,” Paige admitted to reporters in the days leading up to his return. But then he recovered himself, adding, “I think I can still pitch and help this club.”

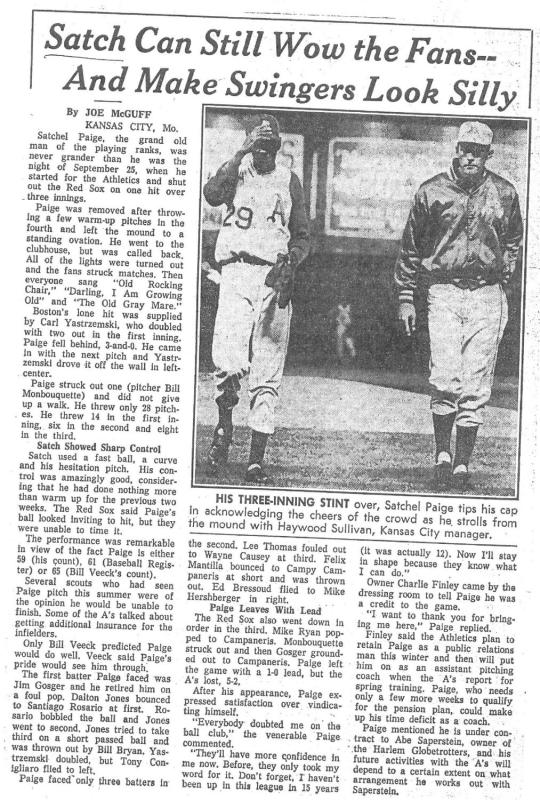

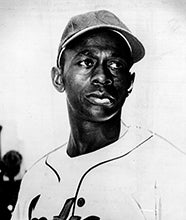

Satchel Paige relaxes in a special chair while playing with the Triple-A Miami Marlins. Paige pitched with Miami from 1956-58. BL-1843-63e (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Share this image:

Still Untouchable

Paige was equal in showmanship to Finley, and he helped the owner all he could between innings. He sat in a rocking chair beside the A’s underground bullpen (“At my age, I’m close enough to being below ground as it is,” Paige explained) with a nurse on hand to run liniment into his aging right shoulder and an errand boy to grab him fresh glasses of water.

But when it was time to play ball, Paige was all business. Boston centerfielder Jim Gosger began the game with a pop out. Then Dalton Jones reached second base on an error but was caught stealing. Up came future Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski, whose father, Carl Sr., had faced Satchel in a Long Island semi-pro game nearly 20 years before.

After running the count to 3-0, Yastrzemski lifted a pitch the left center field wall for a double. As it turns out, Yaz would collect the only hit against Paige.

One by one, the Red Sox went down in order. Young slugger Tony Conigliaro, who had boasted before the game that he would crush the old man’s offerings, popped out. The next six Boston batters looked just as meek.

“Satchel had better swings off me than I had off him,” declared opposing pitcher Bill Monbouquette. A’s third baseman Ed Charles told reporters that Paige had only thrown 10 warm-up pitches, and threw a mid-80s fastball that danced around the hitters’ knees.

The fabled descriptions of Paige’s repertoire was familiar, and so was the score line: Three innings, one hit, one strikeout, no runs. All of it on only 28 pitches. All of it at 59 years of age.

Manager Haywood Sullivan brought Paige back out for warmup pitches in the fourth so that the crowd could send him off with a standing ovation. Afterwards in the clubhouse, Paige began to change into his street clothes before he was summoned back to the field once again. When he returned, he found the stadium lights shut off. The darkened grandstands flickered with lighters and matches as the crowd serenaded Paige with a rendition of “The Old Gray Mare.”

Many long years ago,

The old gray mare, she kicked on the whiffletree,

Many long years ago.

The old gray mare, she ain't what she used to be.

It seemed like a swan song to most everybody, but Paige, always eager to prove them wrong, saw his historic appearance as just the beginning.

“Now I’ll stay in shape,” Satchel told reporters after the game, “because now they know what I can do.”

'Maybe I'll pitch forever'

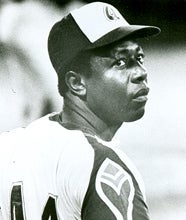

Paige never got another last chance, as his three innings at age 59 would be the final frames on his major league ledger. He would continue to pitch however, including a memorable appearance in 1968 (now at age 62) for the Triple-A Richmond Braves, when he retired Hank Aaron on three pitches in an intrasquad exhibition.

“Aaron tried to time the pitch,” wrote The Atlanta-Journal Constitution’s Wilt Browning of Paige’s third looping delivery. “He made a mighty swing. The ball clicked weakly against the top of Aaron’s bat and flew softly, with little arc, to the waiting third baseman for the out.

“The old man pounded his bony fist into his glove with the sort of youthful joy all of us could understand.”

"If Satch and I were pitching on the same team, we would clinch the pennant by July fourth and go fishing until World Series time."

In 1971, the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s newly formed Committee on Negro Leagues named Paige as its first electee, opening the door for many talented but less heralded Negro League stars in Cooperstown in the years to come. Satchel was the main attraction for the Induction Ceremony on Aug. 9, 1971, and in his speech he explained how he picked up his James Brown-like qualities that made him the hardest-working showman in baseball.

“We played up in Canada and if I didn’t pitch every day they didn’t want the ball club,” said Paige. “And that’s how I started to pitching every day. I pitched in 165 ball games in a row because if I didn’t pitch they didn’t want the club in town, let alone there. So, I began to learn how to pitch by the hour, or by the week, or whatever you may call it. And so I guess all that got me up here to Cooperstown.”

Matt Kelly is the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Museum’s Film Fest a hit with fans, filmmakers

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

#CardCorner: 1971 Topps Jerry Grote

Satch's Swan Song

Babe Ruth clubs his first major league homer

1989 Hall of Fame Game

The Babe of Fenway

Ernie Banks wins second straight NL MVP award

1975 Hall of Fame Game

BA MSS 67, Folder 21, Corr_1958_12_28

01.01.2023

Today’s Game Era Committee Ballot to Be Considered Dec. 4 at Baseball’s Winter Meetings

01.01.2023