- Home

- Our Stories

- A Century-Old Tradition

A Century-Old Tradition

More than a century ago, in the summer of 1912, athletes from the United States won 65 medals at the Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, sharing first place in the overall medal count with the host country. That impressive showing was nothing new. In fact, at the conclusion of the Stockholm games, the USA had amassed 410 medals since the Olympics were re-introduced in 1896 – nearly twice as much hardware as runner-up Great Britain, with 228 medals. (If one includes the medals earned in the oft-overlooked 1906 Games, the U.S. outpaces Great Britain 434 to 232.)

Why did the United States fare so well in the Olympics? Historians offer various explanations, but former ballplayer turned sporting goods mogul A.G. Spalding forwarded a unique perspective in his Official Base Ball Guide for 1913:

I may be a prejudiced judge, but I believe the whole secret of these continued successes is to be found in the kind of training that comes with the playing of America’s national game, and our competitors in other lands may never hope to reach the standard of American athletes until they learn this lesson and adopt our pastime.

Spalding continued:

An analysis of the 1912 Olympian Games shows that the American showed to best advantage in contests where the stress of competition was hardest. In the dashes they were supreme; in the hurdles they were in a class by themselves, and in the high jump and pole vault there was no one worthy of their steel. Whenever quick thinking and acting was required, an American was in front. Does not this fact prove that the American game of base ball enables the player to determine in the fraction of a second what to do to defeat his contestant?

This theory is typical Spalding: Full of bluster and questionable leaps of logic. But you have to hand it to the future Hall of Famer: He was well-aware that he owed his successful career to baseball and promoted the game at every turn. But our National Pastime had more than just an indirect affect on the 1912 Games. Two baseball games were actually played at the Stockholm Olympics, the first time the game was incorporated into the celebrated athletic competition.

The original plan called for two teams comprised of U.S. track-and-field athletes to play an intrasquad game on Wednesday, July 10. The winners would later face the Västerås’ Basebollklubb, a two-year-old club that held the distinction of being the first baseball organization in Sweden. However, the American Olympic Committee balked at this arrangement, as many of the U.S. athletes scheduled to participate in the ball game would still be competing in the events for which they were actually sent to Stockholm. Thus, an alternate arrangement was devised, with the first baseball game to take place on Monday, July 15, the final day of track-and-field events. By that date, enough U.S. athletes would be available to face the Västerås’ Basebollklubb. And the following day, the Americans would stage the intrasquad contest.

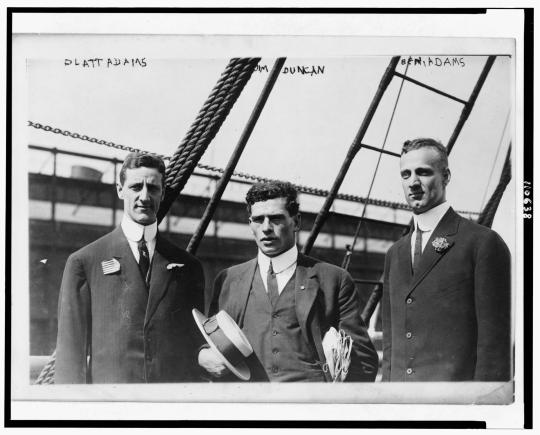

On the morning of July 15, the Americans and Swedes took the field at Östermalm Athletic Ground, the main venue for the Olympic equestrian events. Even though the Americans were track-and-field athletes, not baseball players, it was clear that they would outmatch the Västerås club. For this reason, the U.S. “loaned” four players to the Swedish team to take on the more demanding positions of pitcher and catcher. Ben Adams, who had earlier secured a silver medal in the standing high jump and a bronze in the standing long jump, took the mound for Sweden. And Wesley Oler, a high jumper from Yale, went behind the plate donning a Swedish uniform and the “tools of ignorance.” Frank Nelson, who earned a silver medal in the pole vault, and Harlan Holden, a competitor in the 800-meter dash, also took turns on the mound for Sweden.

The teams agreed to play a six-inning contest, but when the U.S. scored four runs in the first, it quickly became clear that Västerås would be vanquished. Even allowing the Swedish club an extra three outs in the final inning, the Americans emerged with a convincing 13-3 victory.

Besides fielding a winning baseball club, the United States team featured an impressive group of track-and-field athletes, including eight Olympic medalists. And here’s a trivia question that should stump even the most impressive of baseball aficionados: Who was the only member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame to participate in the first baseball game played at the Olympics? The answer: George Wright. The former shortstop for the famous 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings umpired that USA vs. Sweden contest.

For the intrasquad contest that took place the next day, the American contingent split into two teams: the U.S. East and the U.S. West. Abandoning these rather boring titles, the Easts adopted the name “Olympics,” an obvious nod to the event at which the game was played, while the West dubbed themselves the “Finlands,” in honor of the ship (the S.S. Finland) upon which the American athletes sailed to and from the Summer Games.

A total of 20 U.S. athletes took part in this second ball game, with most of the Americans from the previous day’s exhibition taking part in the contest. Additionally, five Olympians who the day before had been busy competing in their track-and-field events (the 4 × 400 meter relay, triple jump and decathlon) joined their compatriots. Included among these was the great Jim Thorpe, the gold-medal winner of both the pentathlon and decathlon events at these Olympics, and a future major league ballplayer.

Given the track-and-field background of each of the ballplayers, it should come as little surprise that aggressive base-running was the order of the day. The large crowd in attendance witnessed no fewer than 14 stolen bases (seven per team), with 800- and 1,500-meter runner Walter McClure leading the pack by pilfering three bags.

After nine innings, the Olympics finished off the Finlands, 6-3, thus ending the sport’s exhibitions in Stockholm. Baseball would resurface sporadically at the Olympics, with additional exhibitions taking place in Berlin (Germany) in 1936, Helsinki (Finland) in 1952, Melbourne (Australia) in 1956, and Tokyo (Japan) in 1964. But it was not until the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles that baseball truly took hold at the Games, first as an official demonstration sport and then, from 1992 to 2008, as a fully recognized official sport of the Olympic Games.

Baseball was voted out of the 2012 Summer Olympics in 2005, the first sport voted out of the Olympics since polo was eliminated in 1936. As of December 2014, the International Olympic Committee signed off on changes that would allow 2020 Summer Olympic organizers to potentially resurrect baseball and softball.

Tom Shieber is the senior curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Baseball at the Olympics

Year, Host City, Status, U.S. Result

1912: Stockholm, Exhibition, U.S. 13, Sweden* 3 and an intrasquad game

1924: Paris, Exhibition, U.S. 5, French* 0

1936: Berlin, Exhibition, Two All-Star U.S. teams played

1952: Helsinki, Exhibition of Pesäpallo,** Two Finnish teams played

1956: Melbourne, Exhibition, U.S. 11, Australia 5

1964: Tokyo, Exhibition, U.S. 6, Japan 2

1984: Los Angeles, Official Demonstration Sport, Silver***

1988: Seoul, Official Demonstration Sport, Gold

1992: Barcelona, Full Medal Event, 4th

1996: Atlanta, Full Medal Event, Bronze

2000: Sydney, Full Medal Event, Gold

2004: Athens, Full Medal Event, Didn't qualify

2008: Beijing, Full Medal Event, Bronze

*Both were local club teams and not national teams

**Finnish version of baseball

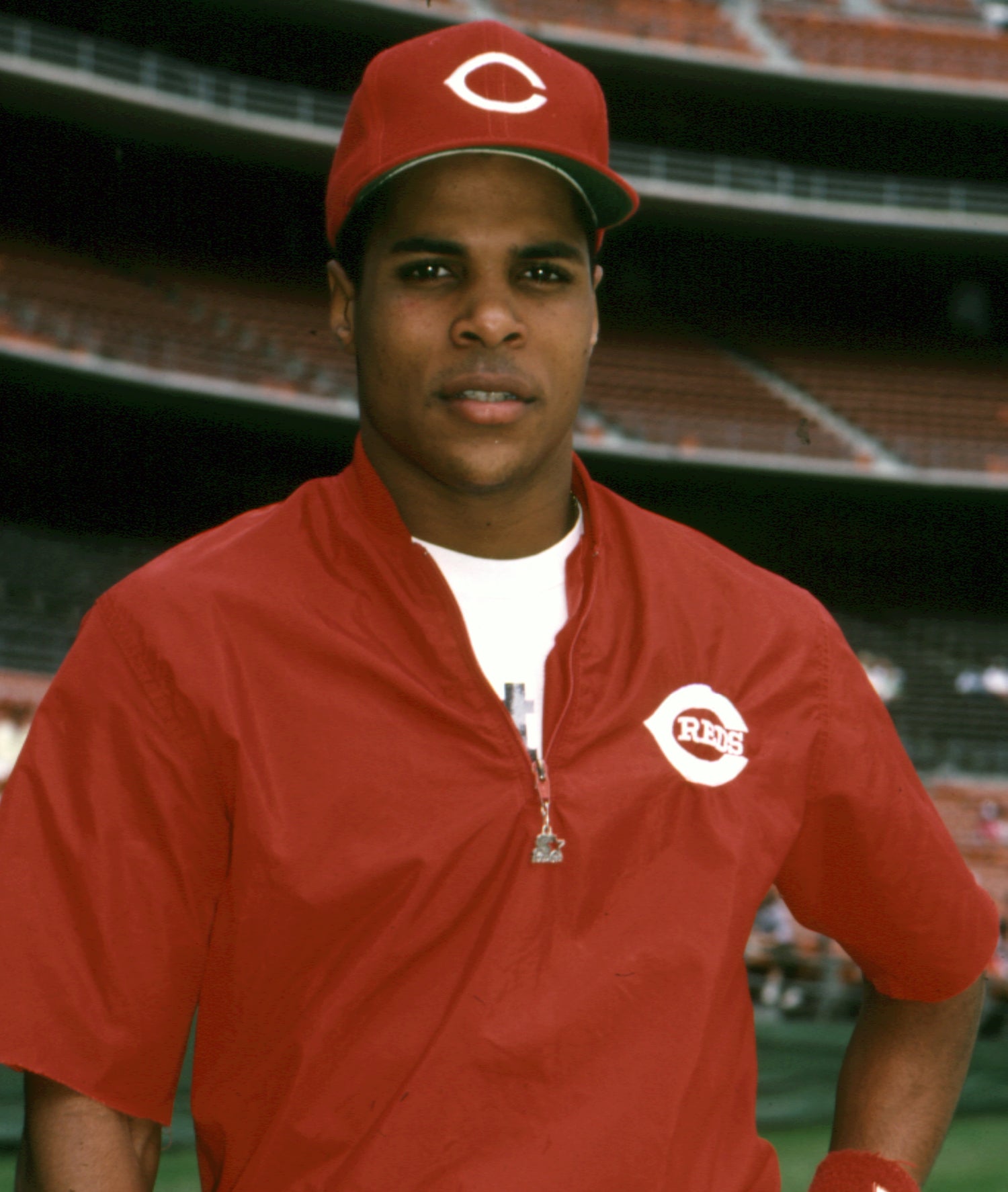

***U.S. team included 2012 Hall of Fame Inductee Barry Larkin