Unless you’ve ever been on the inside and worked with him, there’s no way you can appreciate (Schuerholz’s) baseball intelligence

- Home

- Our Stories

- Hall of Fame Class of 2017

Hall of Fame Class of 2017

The most exclusive team in sports has five new members.

Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines and Iván Rodríguez join John Schuerholz and Bud Selig as the Class of 2017.

Today's Game Era candidates, John Schuerholz and Allan H. “Bud” Selig were elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame on Sunday, Dec. 4, becoming members 313 and 314 of the Cooperstown shrine.

They will join Bagwell, Raines and Rodríguez as the Class of 2017, to be inducted July 30 in Cooperstown as part of the July 28-31 Hall of Fame Weekend. The Weekend festivities will also feature the presentation of the J.G. Taylor Spink Award to Claire Smith for writers and the presentation of the Ford C. Frick Award to Bill King for broadcasting excellence.

Since the inaugural Class of 1936, the National Baseball Hall of Fame has honored the game’s legendary players, managers, umpires and executives. Included in the 317 Hall of Famers are 220 former major league players, 30 executives, 35 Negro Leaguers, 22 managers and 10 umpires. The BBWAA has elected 124 candidates to the Hall while the veterans committees (in all forms) have chosen 167 deserving candidates (96 major leaguers, 30 executives, 22 managers, 10 umpires and nine Negro Leaguers). The defunct “Committee on Negro Baseball Leagues” selected nine men between 1971-77 and the Special Committee on Negro Leagues in 2006 elected 17 Negro Leaguers.

There are currently 74 living members.

Voting Results

BBWAA

| Ballots Cast: 442 | Needed for Election: 332 |

| Votes | Percentage | |

| 381 | Jeff Bagwell | 86.2% |

| 380 | Tim Raines | 86.0% |

| 336 | Iván Rodríguez | 76.0% |

| 327 | Trevor Hoffman | 74.0% |

| 317 | Vladimir Guerrero | 71.7% |

| 259 | Edgar Martínez | 58.6% |

| 239 | Roger Clemens | 54.1% |

| 238 | Barry Bonds | 53.8% |

| 229 | Mike Mussina | 51.8% |

| 199 | Curt Schilling | 45.0% |

| 151 | Lee Smith | 34.2% |

| 105 | Manny Ramírez | 23.8% |

| 97 | Larry Walker | 21.9% |

| 96 | Fred McGriff | 21.7% |

| 74 | Jeff Kent | 16.7% |

| 59 | Gary Sheffield | 13.3% |

| 45 | Billy Wagner | 10.2% |

| 38 | Sammy Sosa | 8.6% |

| 17 | Jorge Posada | 3.8% |

| 3 | Magglio Ordóñez | 0.7% |

| 2 | Édgar Rentería | 0.5% |

| 2 | Jason Varitek | 0.5% |

| 1 | Tim Wakefield | 0.2% |

| 0 | Casey Blake | 0.0% |

| 0 | Pat Burrell | 0.0% |

| 0 | Orlando Cabrera | 0.0% |

| 0 | Mike Cameron | 0.0% |

| 0 | J.D. Drew | 0.0% |

| 0 | Carlos Guillén | 0.0% |

| 0 | Derrek Lee | 0.0% |

| 0 | Melvin Mora | 0.0% |

| 0 | Arthur Rhodes | 0.0% |

| 0 | Freddy Sanchez | 0.0% |

| 0 | Matt Stairs | 0.0% |

*All candidates in italics received less than 5% of the vote on ballots cast and will be removed from future BBWAA consideration

Today's Game Era

12 Votes Needed for Election

- John Schuerholz

16 votes, 100% - Bud Selig

15 votes, 93.8% - Lou Piniella

7 votes, 43.8%

Harold Baines, Albert Belle, Will Clark, Orel Hershiser, Davey Johnson, Mark McGwire and George Steinbrenner each received fewer than five votes.

Jeff Bagwell

The story is so famous, it has become the first cautionary tale for every new big league general manager.

The Boston Red Sox, desperate for bullpen help during the 1990 stretch drive, target the Astros’ Larry Andersen – a 37-year-old veteran of four teams who has posted earned-run averages below 2.00 for each of the two previous seasons.

In exchange, the Red Sox offer a 22-year-old Double-A third baseman who is batting .333 for the New Britain Red Sox but has only four home runs. But a little more than 400 days later, Jeff Bagwell wrapped up a rookie season in Houston where he hit .294 with 15 homers and 82 RBI – a season that would eventually win him the 1991 National League Rookie of the Year Award by a near-unanimous vote.

It was the beginning of a career that would take Bagwell to the Hall of Fame.

Born May 27, 1968, in Boston, Bagwell was the Red Sox’s fourth-round draft choice in 1989. He had received little attention as a high school player in Middletown, Conn., but found a place on the University of Hartford squad.

A lifelong Red Sox fan, the trade to the Astros devastated Bagwell – at first. But soon, Bagwell saw the trade as the platform that eventually launched his career.

After his Rookie of the Year season, Bagwell’s power numbers continued to climb before beginning an assault on the record books in 1994. That season, Bagwell hit .368 with 39 homers and 116 RBI in just 110 games in a season that was cut short by a strike, winning the NL Most Valuable Player Award. Suddenly, fans and media alike began to take note of the first baseman – the Astros moved him across the diamond before his big league career even began – with the shoulder-wide batting stance and fearless disposition.

Bagwell continued to put up astounding numbers in the next decade, scoring 100-or-more runs in eight of nine years from 1996-2004 and driving in more than 100 runs seven times in that span. He also averaged better than 113 walks a year during those seasons.

From 1996 through 2001, Bagwell totaled at least 30 home runs, 100 runs scored and 100 RBI per season – making him one of just six players in history (along with Alex Rodriguez, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Babe Ruth and Albert Pujols) to reach those marks in at least six straight years.

Perhaps most importantly, Bagwell turned the Astros into an annual postseason contender – helping Houston advance to the playoffs six times from 1997-2005.

But early in the 2005 season, Bagwell removed himself from the lineup due to a right shoulder that had caused him four years of constant pain. The arthritic condition – produced by bone-on-bone wear and tear – left him virtually unable to throw a baseball.

Bagwell willed himself back onto the Astros’ roster for their 2005 run to the World Series, but called it quits after he was unable to appear in any games in 2006.

The final numbers: a .297 batting average and Houston club records of 449 home runs and 1,529 RBI (good for 49th all-time and just eight behind Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio).

His 1,401 walks rank 28th all-time, and his .408 on-base percentage ranks 39th. Bagwell was selected to four All-Star Games, finished in the top 10 in the National League MVP voting six times, won three Silver Sluggers and also captured a Gold Glove Award in 1994.

Tim Raines

Tim Raines finished his big league career as the most successful base stealer – ranked by percentage – in MLB history.

He is now a part of baseball’s most exclusive club: The one percent of big leaguers who have been elected to the Hall of Fame.

Born Sept. 16, 1959 in Sanford, Fla., Raines was selected in the fifth round of the 1977 amateur draft by the Montreal Expos. During his first full season in the big leagues in 1981, he batted .304 with 71 stolen bases in a strike-shortened campaign – electrifying fans with his speed. He finished second in Rookie of the Year voting, 19th in MVP voting and earned his first All-Star selection.

Raines earned All-Star Game selections in each of his first seven full seasons. He finished in the top 10 in MVP voting three times and won a Silver Slugger and a batting title in 1986 with a .334 average. He led the league in stolen bases from 1981-1984 and in runs scored in 1983 and 1987.

In 1991, after 13 years in Montreal, Raines signed with the White Sox as a free agent. After five years on the South Side, Raines went to the Yankees and got a taste of postseason success. Raines helped the Bronx Bombers to World Series Championships in 1996 and 1998.

Six months after signing a free agent contract with the Athletics in 1999, Raines was diagnosed with lupus. He spent the rest of the year and all of 2000 undergoing treatment and recovery.

During his 23-year career, Raines recorded 2,605 hits, 980 RBI and a .294 batting average. He hit better than .320 for three in a row (1985-87) and his 808 stolen bases ranks fifth all-time.

Tim Raines finished his big league career with the highest percentage of stolen bases of any player with 400-plus steals.

Iván Rodríguez

The numbers are staggering for Iván Rodríguez, including the 14 All-Star Game selections and 13 Gold Glove Awards – both tops for any catcher in history.

But the best indicator of Rodríguez’s excellence may be his 2,427 games behind the plate. No one has caught more games at the big league level, and few can say they did it as well.

Born Nov. 27, 1971 in Manatí, Puerto Rico, Rodríguez was raised in Vega Baja and grew up learning the game in his baseball-crazed home country, beginning his catching career in Little League. He signed a free agent contract with the Rangers at age 16 in 1988, as the MLB Draft rules then in place did not extend to Puerto Rico.

By 1991, Rodríguez was considered one of the best catching prospects in the game – and was regarded as possibly having the best arm of any catcher in baseball before he even got to the big leagues. He made his debut with the Rangers on June 20, 1991 and finished fourth in the Rookie of the Year voting that year after hitting .264 with three homers and 27 RBI in 88 games. Defensively, he was as advertised – erasing 49 percent of the runners who tried to steal on him.

In 1992, he won the first of his 13 Gold Glove Awards and appeared in his first All-Star Game. And quickly, his offense caught up with his defense – as he topped the .300 mark in batting average for the first of eight straight years in 1995 while steadily adding power to his repertoire at the plate.

In 1999, Rodríguez put it all together – winning the American League Most Valuable Player Award by hitting .332 with 35 home runs, 113 RBI, 116 runs scored and 25 stolen bases. He became just the eighth catcher in history to post a season with at least 100 runs scored and 100 RBI, something no one has done since.

Rodríguez left the Rangers via free agency following the 2002 season, signing a one-year deal with the Florida Marlins. He proved to be the missing piece in Miami, hitting .297 with 16 homers and 85 RBI to lead Florida into the postseason. With the lights shining brightest, Rodríguez excelled – winning the NLCS MVP and eventually propelling the Marlins to the World Series title.

Following his one-year stint in Florida, Rodríguez signed with Detroit, bringing veteran leadership to a team that had lost an American League-record 119 games in 2003. The Tigers improved by 29 games in 2004 as Rodríguez hit .334 and won his seventh (and final) Silver Slugger Award.

By 2006, the man known as “Pudge” had led the Tigers to the World Series.

Rodríguez spent his final three seasons with the Yankees, Rangers, Astros and Nationals. By the time he retired following the 2011 season, he had totaled 2,844 hits – the most of any big leaguer who played at least 50 percent of his games behind the plate.

All totaled, Rodríguez hit .296 with 311 home runs, 572 doubles (26th on the all-time list among all players), scored 1,354 runs (best all-time among catchers) and drove in 1,332 runs (fifth all-time among catchers).

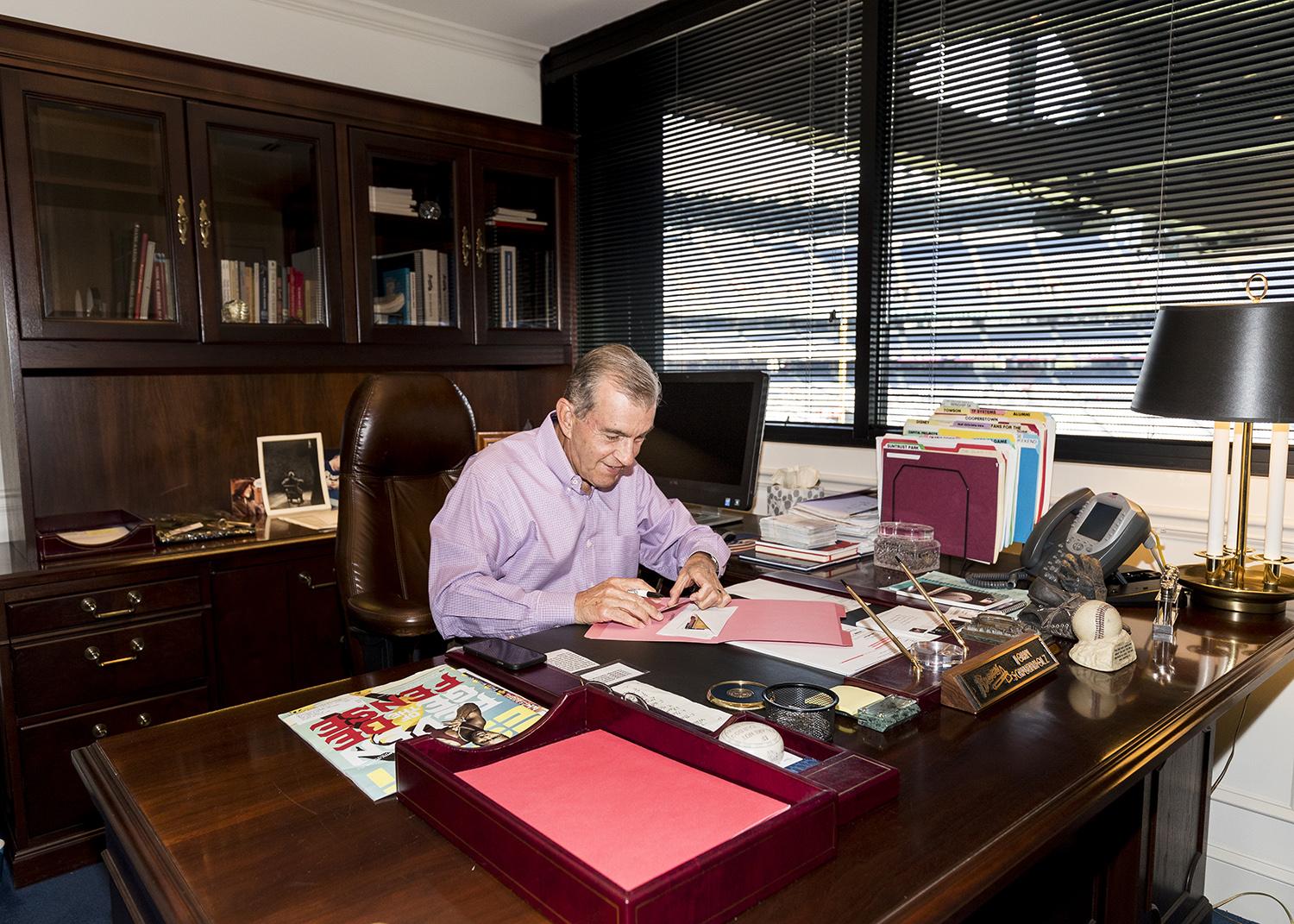

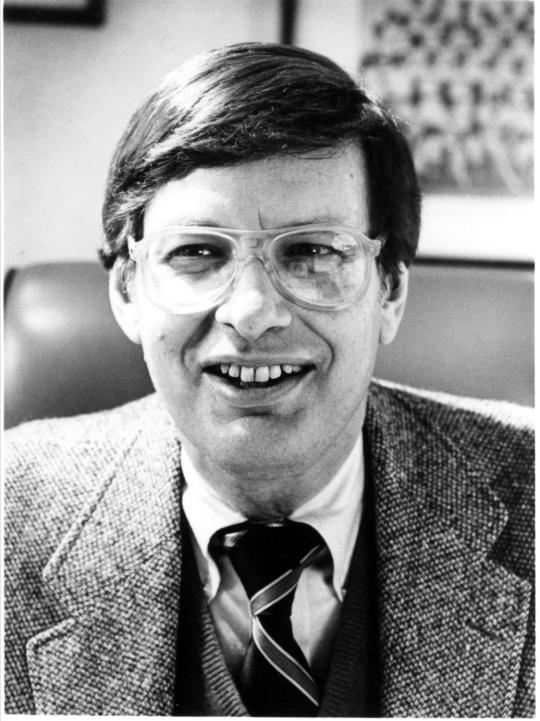

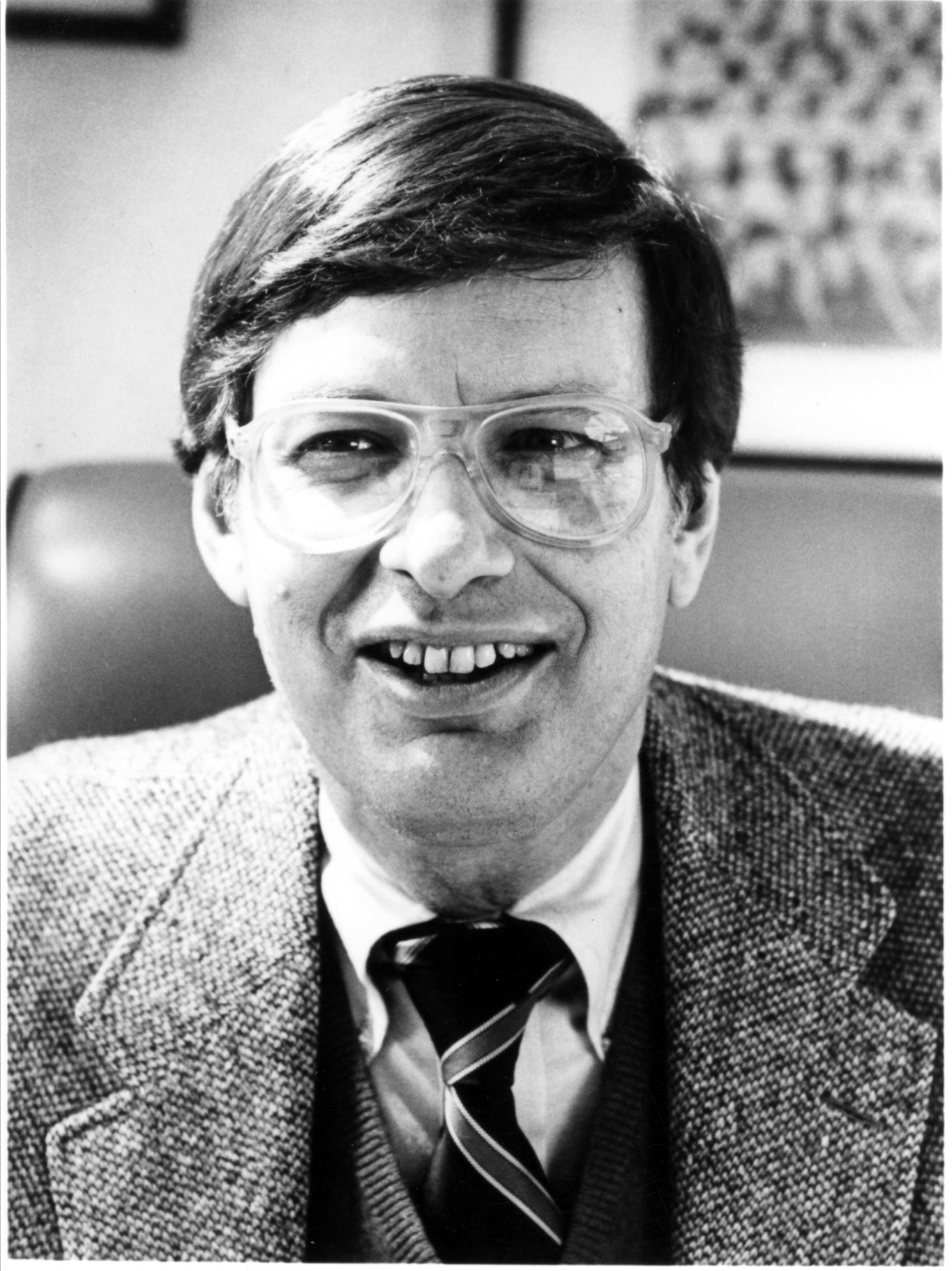

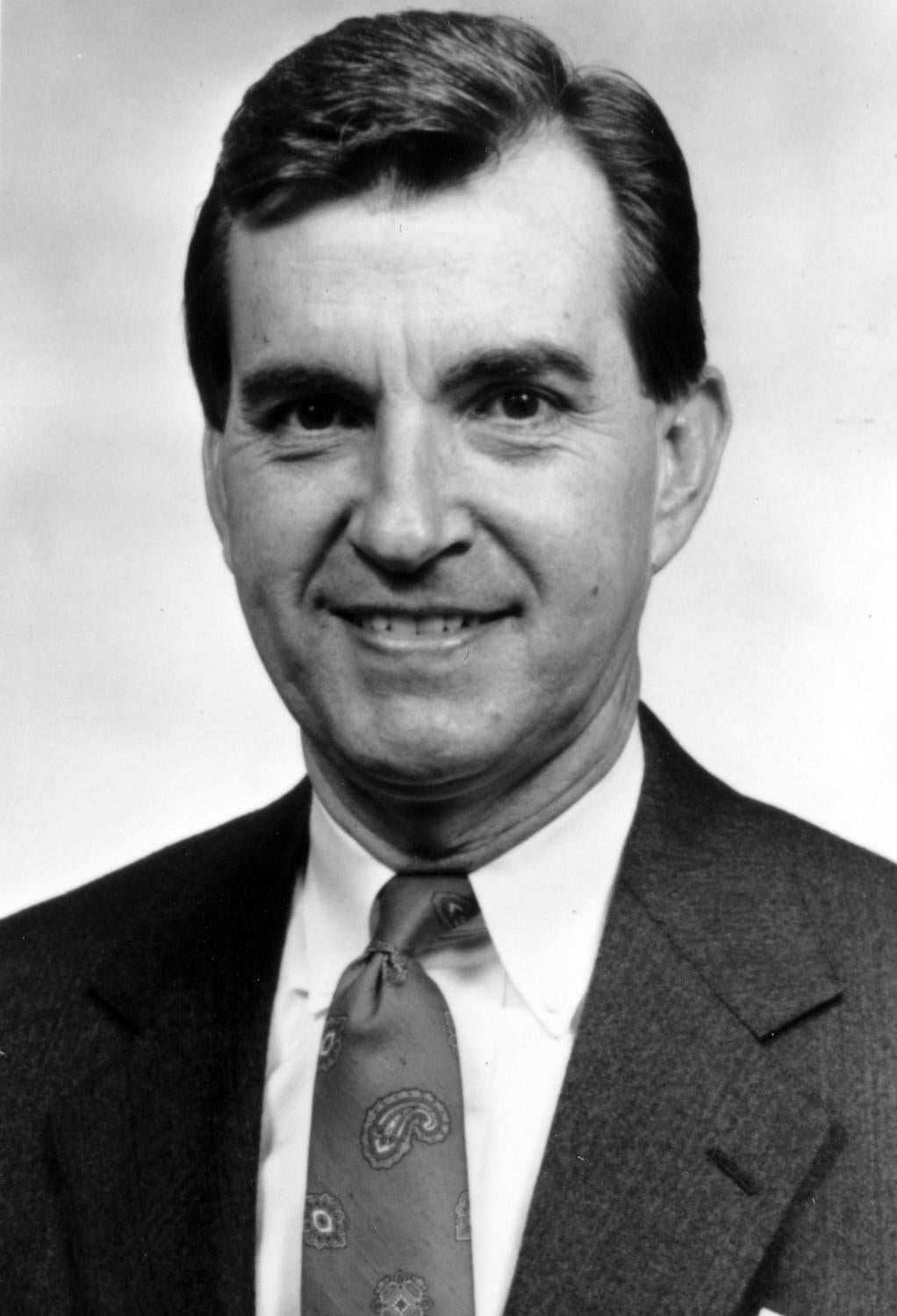

John Schuerholz

Born Oct. 1, 1940, Schuerholz was raised in Baltimore. His father, John, was a minor league second baseman in the Philadelphia A’s organization before a broken leg derailed his career.

Schuerholz followed his father’s footsteps in high school as a second baseman, but received no offers after graduating and instead enrolled at nearby Towson University. There, Schuerholz was an all-conference selection in both baseball and soccer and was named Athlete of the Year during his senior season.

With his degree in hand, Schuerholz became a junior high teacher in the Baltimore suburb of Dundalk. But in 1966, Schuerholz took one last shot at a baseball career – sending a letter of inquiry to Jerold Hoffberger, the president of the National Brewing Company and chairman of the Orioles.

The letter found its way to Orioles president Frank Cashen, who personally replied to every letter he received. That brought Schuerholz to the attention of Orioles director of player development Lou Gorman, who hired Schuerholz as a personal assistant.

Two years later, Gorman joined the front office of the expansion Kansas City Royals, and Schuerholz went with him.

“The very first day I started in that job (with the Orioles), my goal was to become a general manager of a Major League Baseball team,” Schuerholz said. “I gave myself five years, after which I would assess where I was in my career – because I felt I could always go back to teaching if I didn’t succeed.”

Five years into his baseball career, Schuerholz was still working for Gorman – helping lay the foundation for the talented Royals teams of the late 1970s that featured homegrown stars Frank White, Al Cowens and future Hall of Famer George Brett. Gorman was named the Royals’ general manager in the fall of 1975, and Schuerholz became the team’s farm director.

Then in early 1976, Gorman left to run the expansion Seattle Mariners – and Schuerholz was promoted to director of scouting and player development for the Royals. In 1979, Schuerholz was named Vice President of Player Personnel.

In 1981, Schuerholz took over for Joe Burke as the Royals’ general manager when Burke was promoted to team president.

“Unless you’ve ever been on the inside and worked with him, there’s no way you can appreciate (Schuerholz’s) baseball intelligence,” said former Braves executive Paul Snyder.

Schuerholz took over a Royals franchise that won four American League West titles in five years (1976-78, 1980) and an AL pennant (1980), but seemed to be in transition. By 1985, Schuerholz had re-tooled much of the team with younger talent – especially pitchers like Bret Saberhagen, Danny Jackson and Bud Black. In 1985, the Royals won their first World Series title – defeating the Cardinals in a classic seven-game battle.

Following the 1985 season, Schuerholz was named the Executive of the Year by the Sporting News.

“I want to be here. I like it here,” said Schuerholz in 1985. “I have a lot of my blood and sweat in this organization.”

But by 1990, Schuerholz – who signed a “lifetime” contract with the Royals in 1985 – was looking for a different challenge. He found one with the Braves, who had posted losing records from 1984-90 and were searching for a new general manager when Bobby Cox went back to the dugout after a stint as GM. Schuerholz immediately helped the Braves go from worst to first, winning the National League pennant in 1991 after finishing last in the NL West the year before.

Schuerholz inherited talent like Tom Glavine and John Smoltz, but added to the mix by acquiring Greg Maddux, Terry Pendleton and Fred McGriff over the next few seasons.

“(Schuerholz) knows what he wants,” said former Indians general manager John Hart. “He’s always prepared (during trade negotiations), and he doesn’t mince words.”

Under Schuerholz, the Braves embarked on a run unseen in big league history. For 14 seasons from 1991-2005, the Braves finished first in their division in every completed season. Atlanta advanced to the World Series four times in that stretch, winning the 1995 Fall Classic title.

He became the first general manager to lead teams to World Series titles in both the American League and National League.

“We could have been a one-shot wonder,” Schuerholz said during the Braves’ run. “The consistency of or success is a great source of pride for me.”

Schuerholz spent 17 years as the Braves’ general manager, then took over as team president following the 2007 season – a position he still holds.

John Schuerholz inherited talent like John Smoltz (far left) and Tom Glavine (middle left) when he joined the Braves in 1990, and manager Bobby Cox (middle right) was already on the scene. But over the next few seasons, Schuerholz brought in players like Greg Maddux (far right) that combined with the talent on hand to make the Braves a perennial contender. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

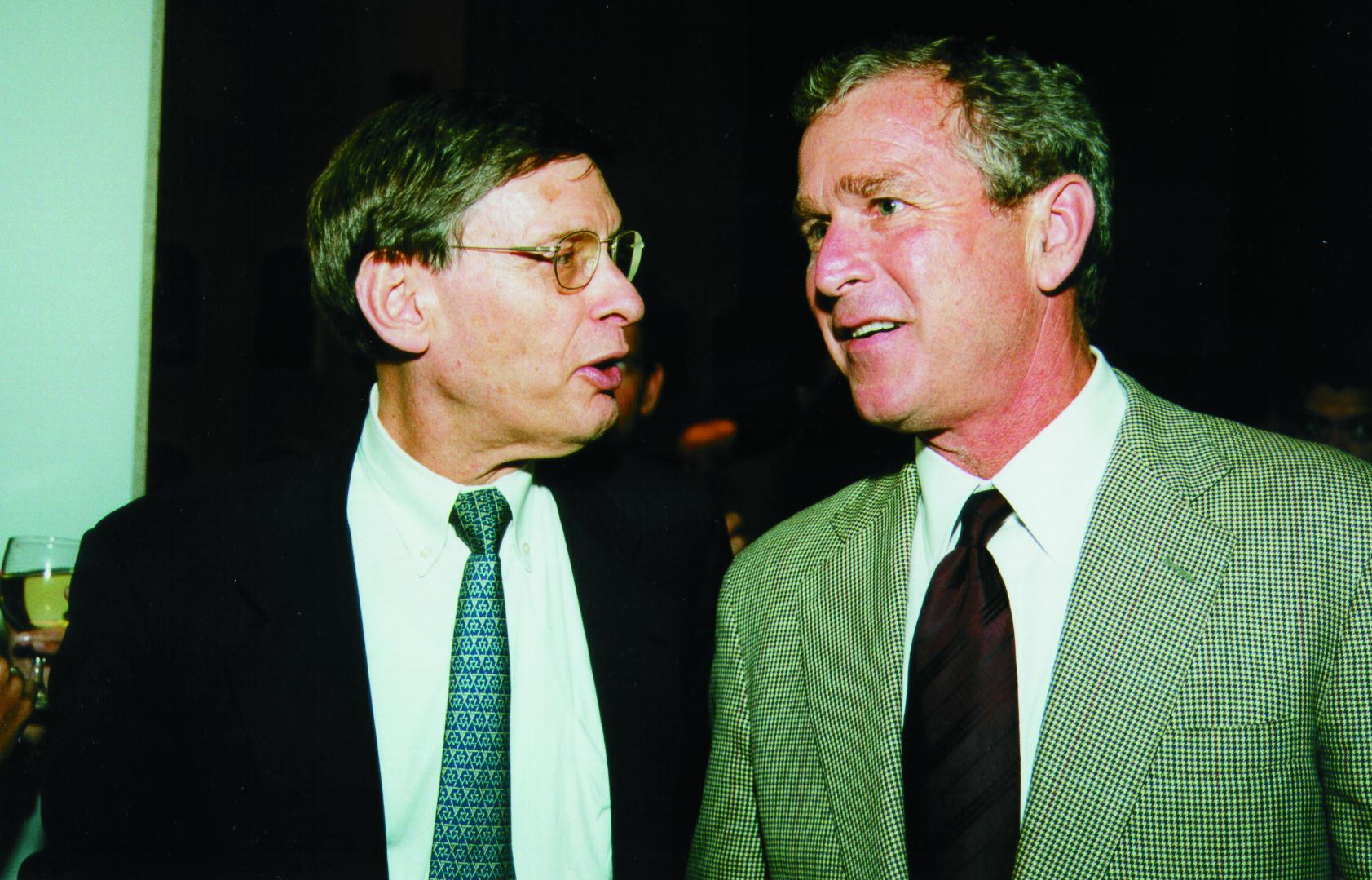

Allan H. “Bud” Selig

Born July 30, 1934, in Milwaukee, Wis., Selig came of age as an ardent baseball fan, giving up the game on the field after “a guy…threw a curve at me and I backed two feet out of the box.” Selig attended games of the minor league Milwaukee Brewers and eventually the Braves when they moved to Milwaukee in 1953. By then, Selig was at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, majoring in American History and Political Science.

He graduated in 1956 and – after a tour in the U.S. Army – joined his father at his Ford dealership in nearby West Allis, Wisc.

“Joe Torre said he bought his first car from me in 1960,” Selig said of the former Braves catcher and future Hall of Famer. “That’s true.”

By 1963, Selig was the largest public stockholder in the Milwaukee Braves.

But by 1965, the Braves had announced they were moving to Atlanta for the 1966 season, ending their 13-year run in Milwaukee. Selig sold his team stock and began work on bringing baseball back to his hometown even before the Braves had left.

After organizing successful exhibition games with MLB teams in Milwaukee, hosting regular season White Sox games at County Stadium and nearly acquiring the White Sox in 1969, Selig finally met his goal when he led a group that purchased the American League’s Seattle Pilots out of bankruptcy court on March 31, 1970. Seven days later, the new Milwaukee Brewers began their 1970 AL schedule.

Under Selig’s ownership, the Brewers grew into a powerhouse, winning the AL pennant in 1982 with a team that featured future Hall of Famers Rollie Fingers, Paul Molitor, Don Sutton and Robin Yount. Selig quickly became one of baseball’s most influential owners, helping identify and hire Peter Ueberroth as commissioner in 1984.

“He should have been Senate majority leader,” said White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, describing Selig’s ability to lobby for his position and form alliances. That skill would be tested when on Sept. 9, 1992 – two days after commissioner Fay Vincent resigned – Selig was named the Chairman of MLB’s Executive Council, making him the de facto commissioner.

Selig was quickly thrust into the battle between labor and management, which culminated with the 1994 strike and the cancellation of that year’s World Series. But with Selig in command, baseball slowly returned to normal with the resumption of play in 1995 and several key events – like Cal Ripken’s chase of Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games played record – that restored the game’s popularity.

On July 9, 1998, the owners removed the “interim” tag and made Selig the game’s commissioner. Over the next 16 years, Selig – whose total tenure as commissioner was exceeded only by that of Kenesaw Mountain Landis – oversaw expansion in 1993 and 1998, the addition of two Wild Card teams, the creation of interleague play, MLB.com, the World Baseball Classic and the introduction of instant replay as a tool for umpires.

“I learned that the best interests of the game are the most important thing,” Selig said. “They transcend my best interests, your best interests and everybody else’s.”

A $1.2 billion industry in 1992, the game’s annual revenues had grown to $9 billion by the time Selig left office in early 2015. He worked tirelessly to create revenue sharing policies that would benefit all teams, recognizing early in his tenure as commissioner that the game was growing and that all teams should benefit. In 2005, he launched the Commissioner’s Initiative on Sustainable Ballpark Operations, becoming the first professional sports league commissioner to create an initiative dedicated to promoting responsible environmental stewardship, which has now become standard practice in sports leagues throughout the United States and the world.

Under Selig, MLB enjoyed 20-plus years of labor peace following the 1994-95 strike and experienced a ballpark boom that featured almost two dozen new stadiums. Selig retired Jackie Robinson's No. 42 throughout baseball in 1997, oversaw the league's expansion into three divisions per league and helped establish the toughest anti-drug measures in all of sport.

“First and foremost,” Selig said, “I’m a fan.”