- Home

- Our Stories

- Maury Wills named one of 10 Golden Era Committee Hall of Fame finalists

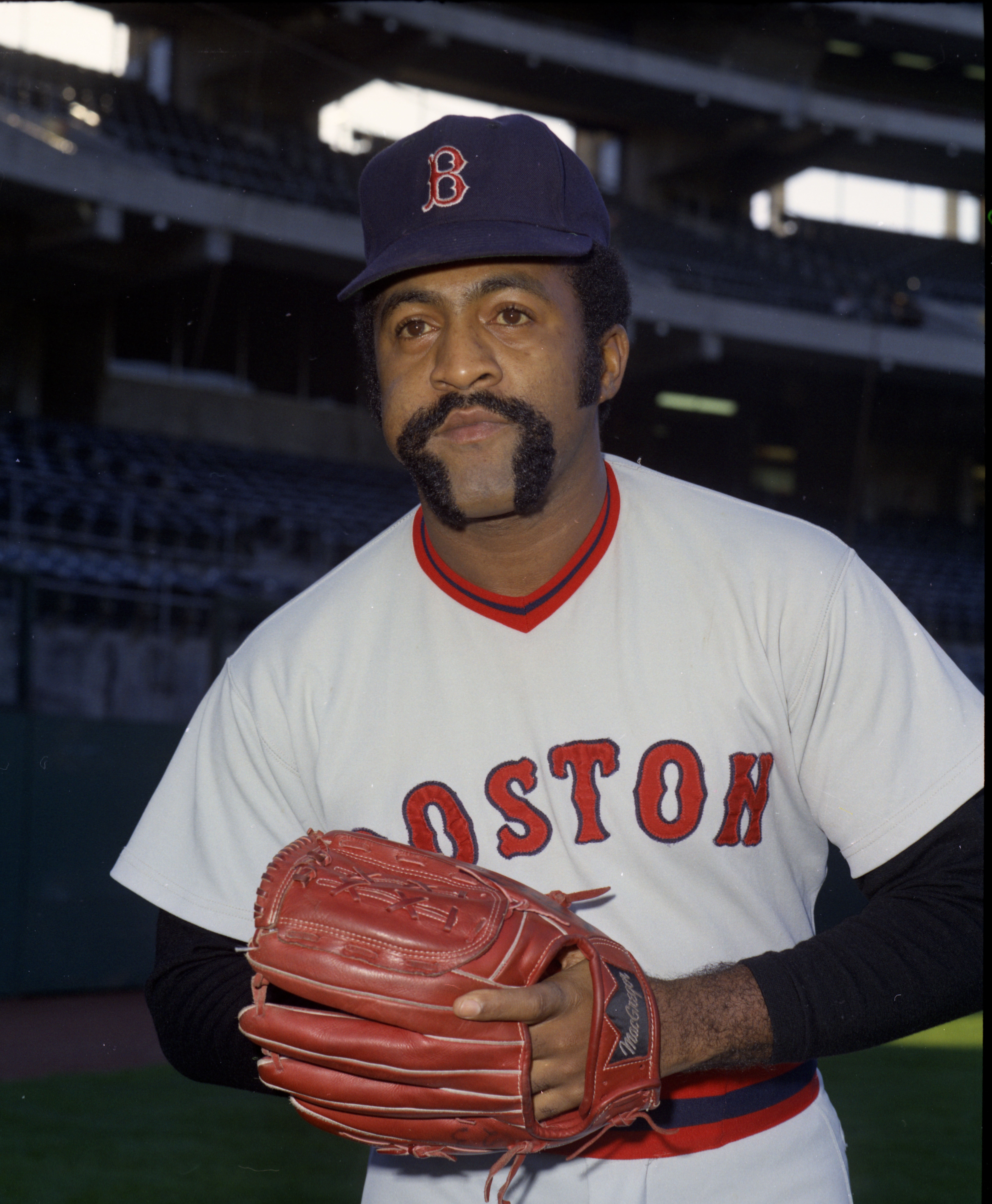

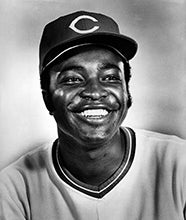

Maury Wills named one of 10 Golden Era Committee Hall of Fame finalists

He redefined what was possible on the basepaths, won the 1962 National League Most Valuable Player Award – en route to receiving MVP votes in seven other seasons – and was named to seven All-Star Games. But Maury Wills’ career might best be summed up by his three World Series rings as a member of the Los Angeles Dodgers teams that scratched for every run they could for a historically excellent pitching staff.

Wills, who ignited the Dodgers offense with speed and fearless play, was more often than not the author of the run support needed by Koufax, Drysdale and the rest of Los Angeles’ arms.

Now, Wills’ unique career path could take him all the way to Cooperstown.

Wills, who played 14 seasons for the Dodgers, Pirates and Expos, is one of 10 finalists on this year’s Golden Era ballot that will be considered by the committee on managers, umpires, executives and long-retired players at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The 16-person committee will vote at baseball’s Winter Meetings in San Diego, Calif., and the results of the vote will be announced Dec. 8.

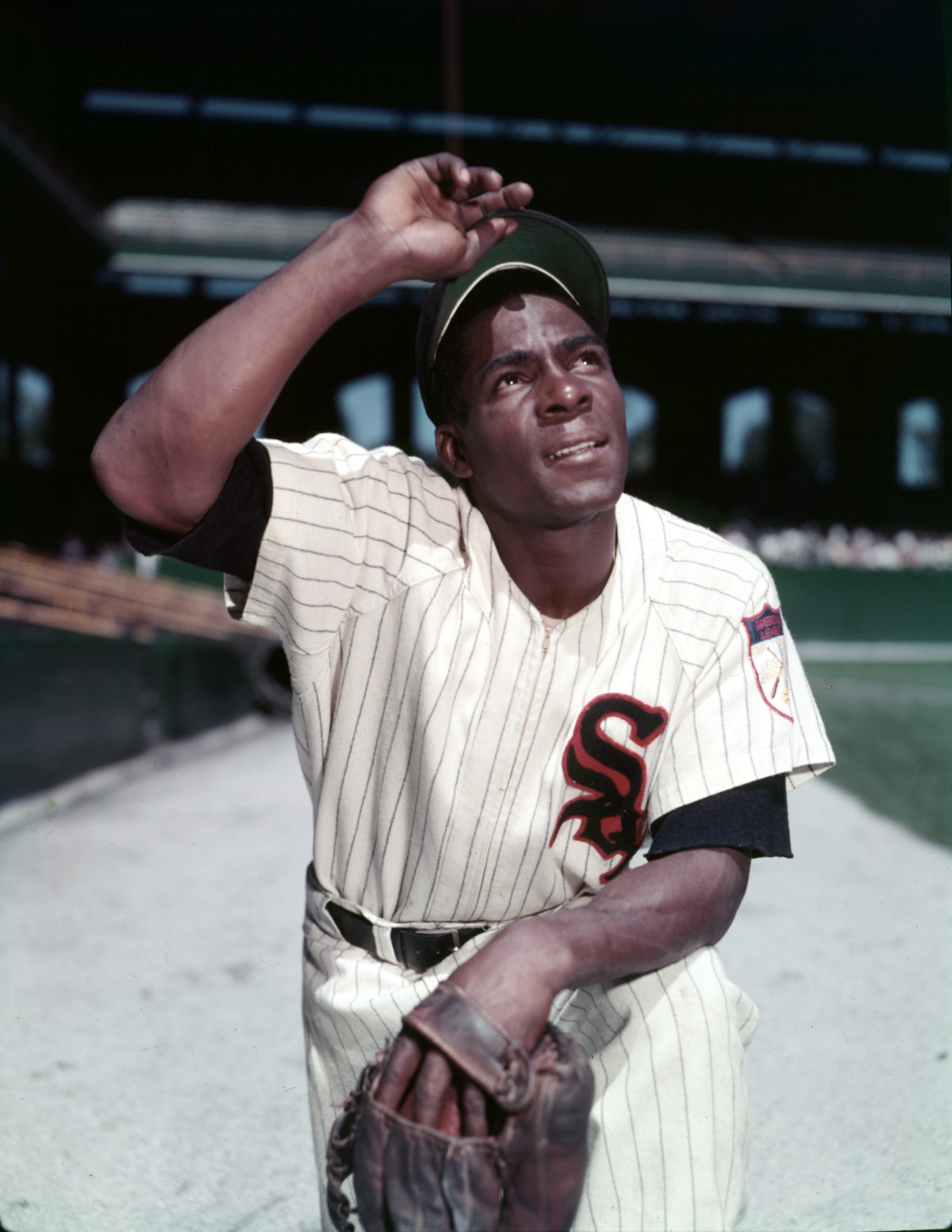

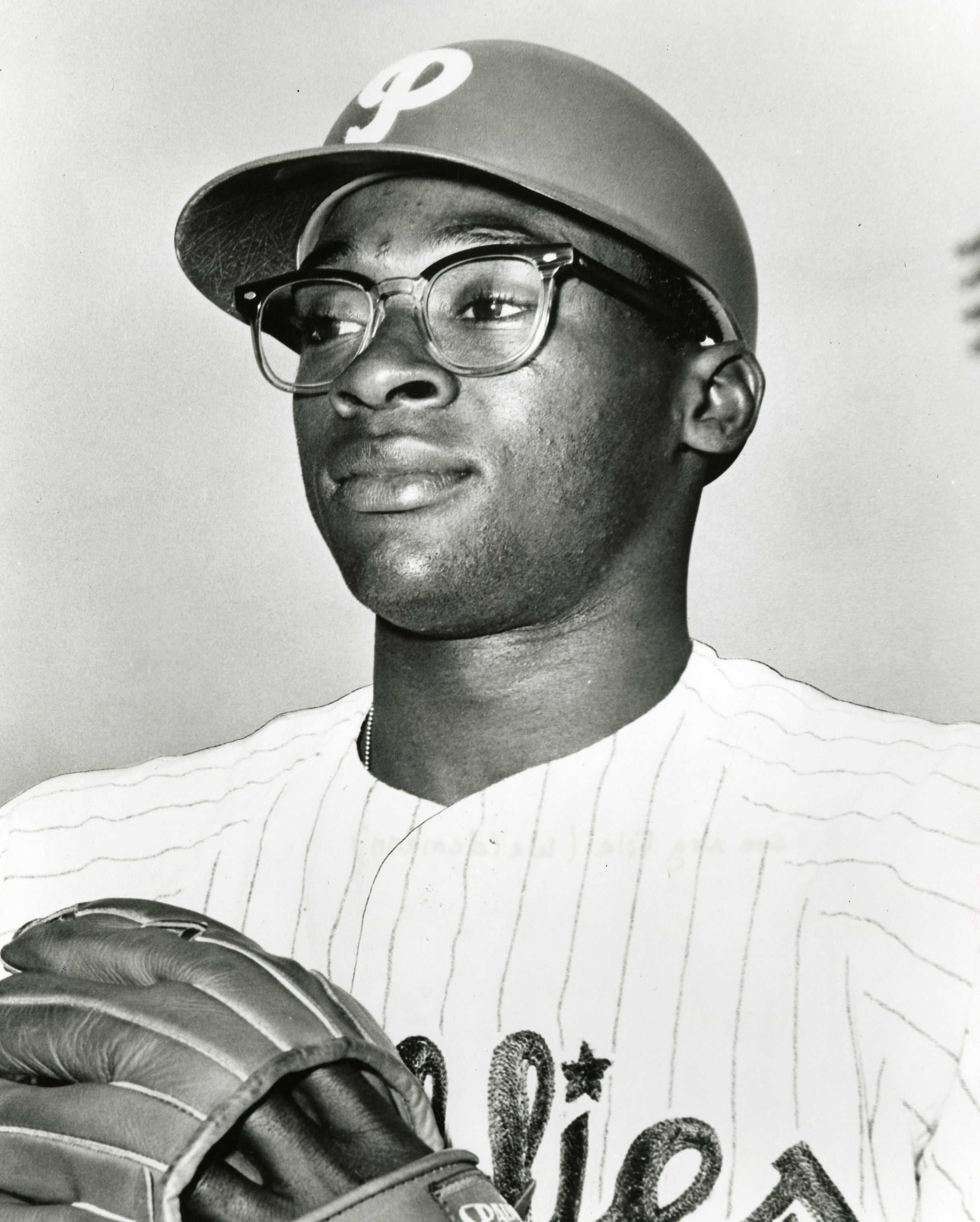

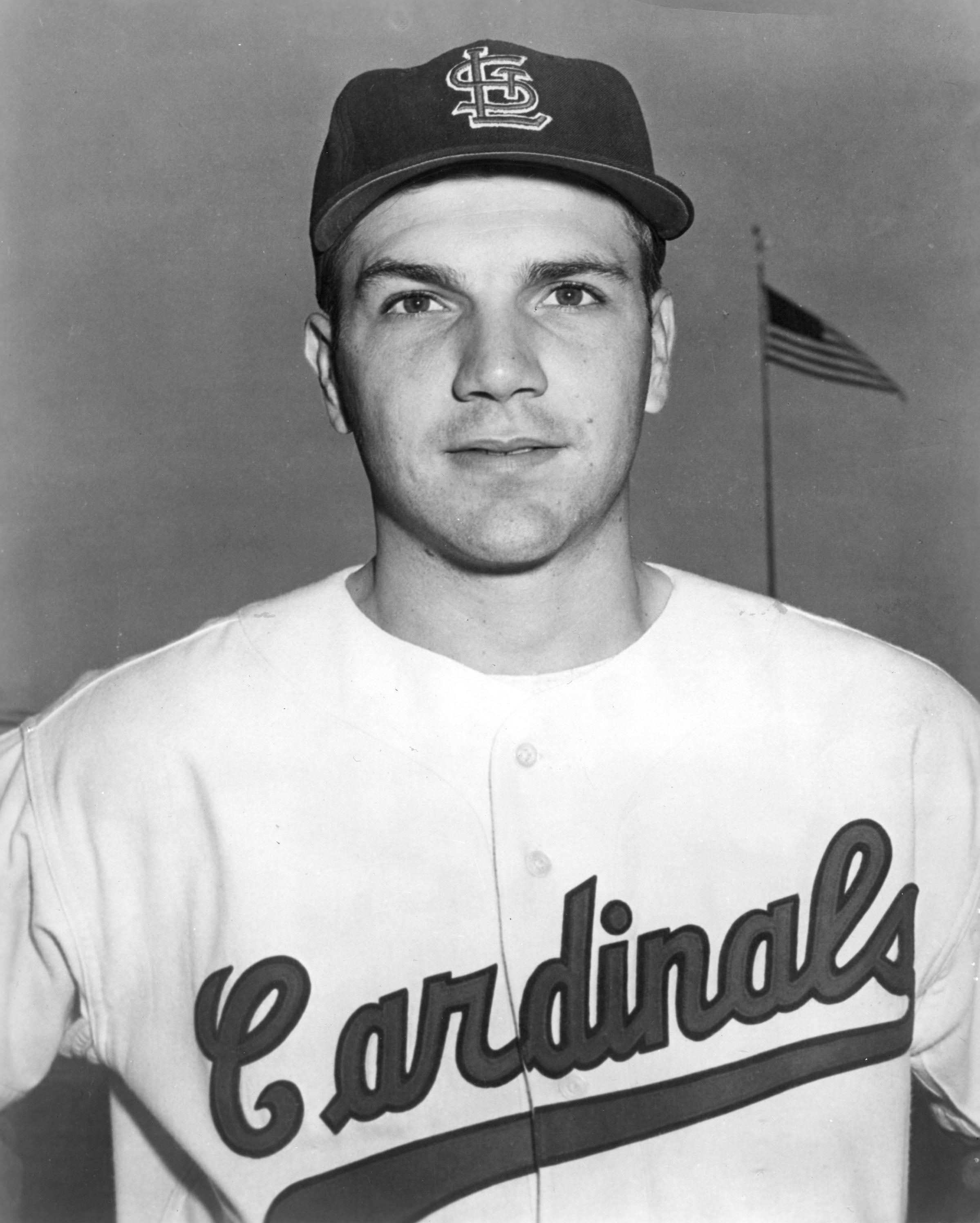

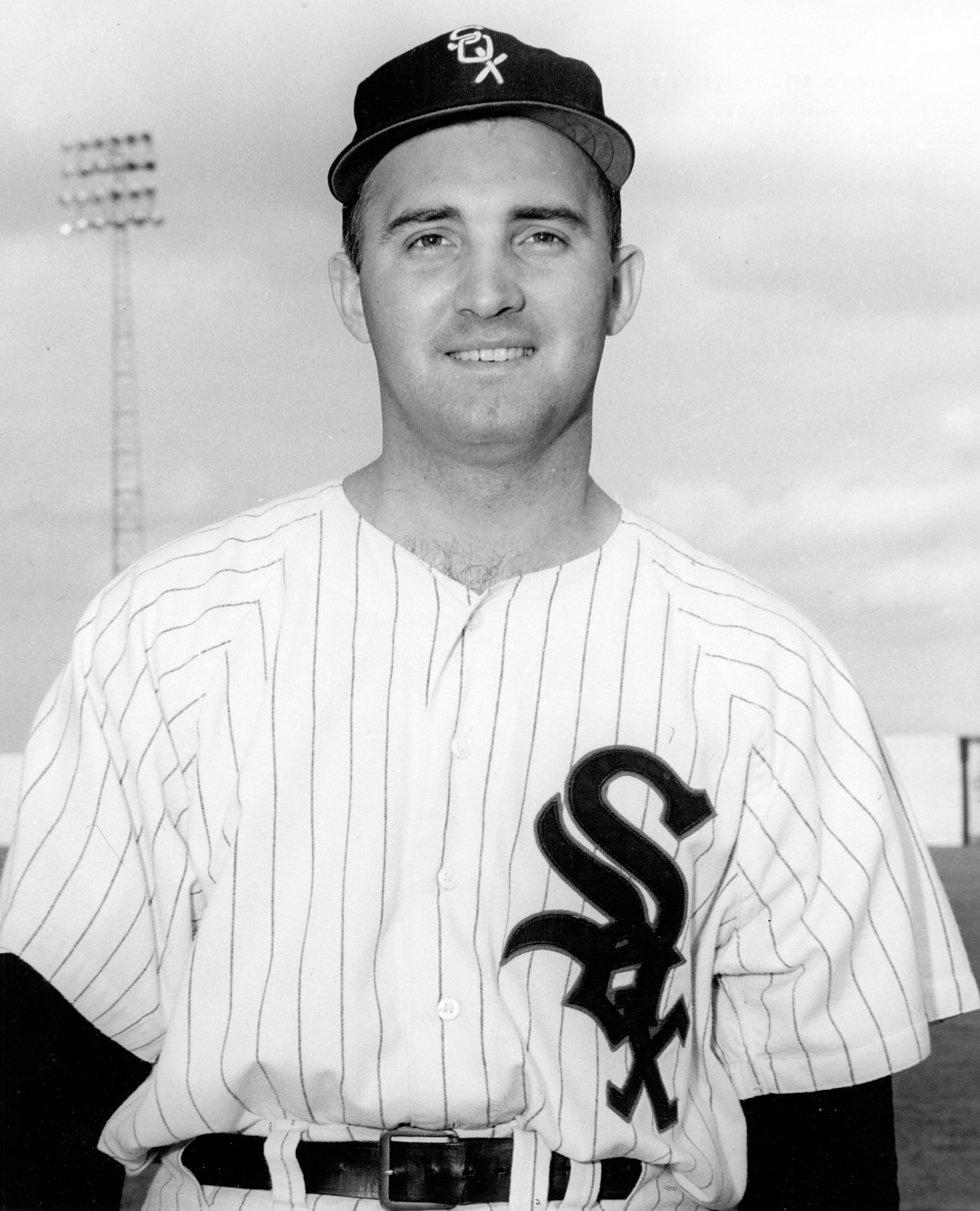

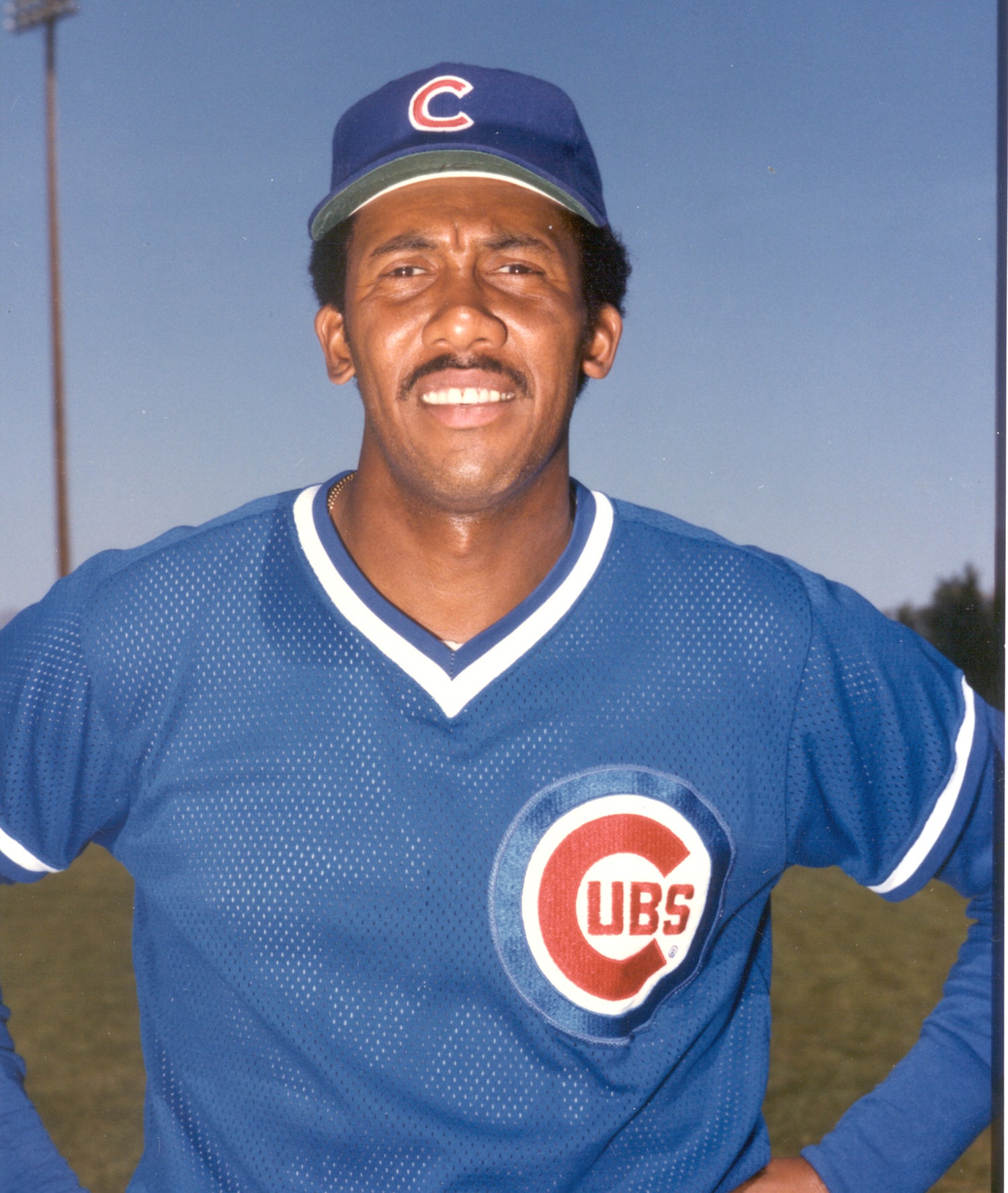

The 10 candidates on the Golden Era Committee ballot are: Dick Allen, Ken Boyer, Gil Hodges, Bob Howsam, Jim Kaat, Minnie Minoso, Tony Oliva, Billy Pierce, Luis Tiant, and Wills. Any candidate who is named on at least 75 percent of all ballots cast will be inducted in the Hall of Fame as part of the Class of 2015.

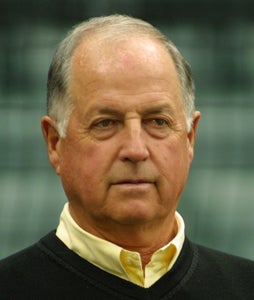

The Golden Era Committee consists of Hall of Famers Jim Bunning, Rod Carew, Pat Gillick, Fergie Jenkins, Al Kaline, Joe Morgan, Ozzie Smith and Don Sutton; baseball executives Jim Frey, David Glass, Roland Hemond, and Bob Watson; and veteran media members Steve Hirdt, Dick Kaegel, Phil Pepe and Tracy Ringolsby.

Bio

Born Oct. 2, 1932 in Washington, D.C., Wills grew up in the nation’s capital as one of 13 children and starred during his prep days as pitcher and as a quarterback on the football field. Upon graduation from high school, Wills signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers, who quickly converted Wills to a position player.

By 1953, Wills was playing shortstop for Class B Miami and seemed fast-tracked for the big leagues. But with future Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese entrenched at shortstop and young Don Zimmer on the horizon, the Dodgers allowed Wills to go to the Reds via the minor league draft following the 1956 season.

But after hitting .267 with 21 stolen bases for the Triple-A Seattle Rainers of the Pacific Coast League in 1957, the Reds returned Wills to the Dodgers. He stole 25 bases with the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in Spokane in 1958, then was sent to the Tigers in the offseason before Detroit sent Wills back to the Dodgers at the dawn of the 1959 campaign.

At that point, Wills was 26 years old and a career minor leaguer. But the 1959 season would prove to be his coming out party.

Again sent to the Pacific Coast League, Wills hit .313 in 48 games with Spokane that spring, stealing 25 bases. And with Zimmer struggling at the plate in Los Angeles, the Dodgers called up Wills for his big league debut on June 6. His numbers the rest of the year – a .260 batting average with 27 runs scored and seven stolen bases in 83 games – weren’t eye-popping, but Wills’ steady play at shortstop proved key as the Dodgers rallied to tie the Braves for the National League pennant before winning the best-of-3 playoff to advance to the World Series.

In the Fall Classic, Wills hit .250 as the Dodgers defeated the White Sox in six games to capture their first World Series title since moving to Los Angeles. They would win two more crowns in the 1960s – with Wills at the forefront of a team that relied on pitching, defense and plenty of speed.

In 1960, Wills won the first of six straight National League stolen base crowns – becoming the first National Leaguer (and only the second big leaguer) to win six consecutive titles. Wills’ 50 steals in 1960 marked the first time an NL player had reached that level since Max Carey in 1923.

“Maury is an inspiration to our players,” said Dodgers manager Walter Alston. “His fiery spirit rubs off on them.”

Following a league-leading 35 steals to go along with 105 runs scored and his first Gold Glove Award in 1961, the switch-hitting Wills set the baseball world on fire in 1962 with a season for the ages. Wills stole 104 bases, breaking Ty Cobb’s modern-era record of 96 thefts in 1915. Wills recorded 208 hits and scored 130 runs in 1962, hitting .299 while leading the league with 10 triples. The Dodgers led the NL race throughout the summer, only to be caught at the wire by the Giants – who defeated Los Angeles in a three-game playoff to advance to the World Series.

In addition to his Most Valuable Player Award, Wills won another Gold Glove Award at shortstop and set a record that might never be broken: Appearing in 165 regular-season games thanks to the three-game playoff.

“I practiced every conceivable play that might arise (so) I’d be ready for anything,” Wills told the Associated Press in 1973.

The next season, Wills posted his first .300 batting average season (.302) while stealing 40 bases for a Los Angeles team that won the National League pennant before sweeping the Yankees in the World Series.

Wills and the Dodgers missed the postseason in 1964, but rebounded to capture the NL flag in 1965. Wills stole 94 bases that season, becoming the first modern-era player with two 90-plus stolen base seasons. The Dodgers defeated the Twins in seven games in the World Series, with Wills tallying 11 hits and three steals.

Wills’ run as stolen base king ended in 1966, but the Dodgers won their third National League pennant in four seasons before falling to the Orioles in the World Series. Wills was named to his seventh All-Star Game that summer, but following the season he was traded to the Pirates for Bob Bailey and Gene Michael. The Dodgers fell to eighth place in the NL in 1967 while Wills became Pittsburgh’s everyday third baseman and helped the Pirates win 81 games by hitting .302 with 186 hits and 92 runs scored.

At 35 years of age in 1968, Wills stole 52 bases for the Bucs while hitting .278 during The Year of the Pitcher. Pittsburgh left Wills unprotected in the 1969 Expansion Draft, however, and he was taken by the Expos – where he played 47 games before being traded back to the Dodgers in a deal that sent Ron Fairly to Montreal.

In Montreal and Los Angeles in 1969, Wills hit .274 in 151 games, stealing 40 bases and finishing 11th in the NL MVP voting. He continued as the Dodgers’ primary shortstop through the 1971 season, hitting .281 in 149 games in ’71 while finishing sixth in the NL MVP voting at the age of 38.

“You can’t do it automatically,” Wills said. “Nothing’s ever automatic in this game. You’ve always got to drive.”

In 1972, prized prospect Bill Russell unseated Wills as the Dodgers shortstop, and Wills retired following the season with a career batting average of .281, 1,067 runs scored, 2,134 hits and 586 stolen bases. His career total in steals ranks 20th all-time – and 16th among modern-era players.

Wills remained in the game after his playing days as a broadcaster and later managed the Seattle Mariners in 1980 and 1981, becoming just the third African American to hold a big league managerial job.

But for a generation of players and fans, Wills’ will always be remembered for changing the game – 90 feet at a time.

“I will never look at the stolen base as not being meaningful,” Wills told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2003. “Nothing upsets the mind of a pitcher as much as good baserunning and base-stealing. Hitters go into slumps from time to time, but good base-stealers keep stealing bases.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

2015 Golden Era Candidate Bios