- Home

- Our Stories

- TV brought baseball to fans who had never seen a game

TV brought baseball to fans who had never seen a game

However clear Bill Stern’s rhetoric was, his subjects were opaque in baseball’s first televised game. Princeton edged Columbia, 2-1, on May 17, 1939, at Baker Field – broadcast to a handful of TV sets in the New York area.

In the stands were about 5,000 people. And due to the nascent technology, the person with the worst view at Baker Field had a better glimpse than the best view at home.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

W2XBS used a single camera fifty feet from home plate – “woefully lacking,” said The New York Times. One camera at one site “does not see the complete field. Baseball by television calls for three or four cameras.” At least the viewer didn’t suffer long. The 10-inning game took just two hours and 15 minutes.

The problem was the picture, which was delivered through NBC’s $150,000 van and relayed to a transmitter atop the Empire State Building, then picked up at local outposts. One 9 by 12 inch screen’s “outset was blurred, with reproduced faces dark,” said The Times. The ball was rarely seen. Players resembled “flies.”

On Aug. 26, 1939, NBC telecast a first professional game: Cincinnati at Brooklyn. "No monitor, only two cameras at Ebbets Field,” said Dodgers’ 1939-53 announcer Red Barber. “I had to watch to see which one’s red light was on, then guess its direction.”

Radio seemed immovable. In 1946, 140 million Americans owned 56 million radios compared to TV’s 17,000. But slowly, television became irresistible: by the mid-1950s, 10,000 TVs were being sold every day.

Springtime for TV baseball was really autumn 1951. The Dodgers and Giants tied for the National League pennant. CBS and NBC then aired a best-of-three playoff: The first national network sports telecast. Next, NBC began TV’s first national World Series. Postseason had a Southern sound: Florida’s Barber; Georgia’s Ernie Harwell and Kentucky’s Russ Hodges of the Giants; and Alabama’s Voice of the Yankees: Mel Allen.

“People ask why so many voices came from the South,” said Harwell. “We grew up in a storytelling place.”

Allen and Barber were baseball’s first two larger-than-life TV Voices, receiving the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s first Ford C. Frick Award for broadcast excellence in 1978. A distant cousin of poet Sidney Lanier, Red made the mound a “pulpit.”

Mel was even more identified with American TV at mid-century: Allen called 21 World Series, so famed that, hailing a cab in Omaha one night, he said simply, “Sheraton, please.” The cabby, not recognizing him in the dark, nearly drove off the road.

Post-World War II’s TV capital was Chicago, having one of every 10 TV sets by 1947. New York WPIX and WOR were first to put baserunner and closeup cameras near each dugout and first and third base. In 1951, WGN Chicago invented today’s center field camera. "A guy saw a schoolboy scoreboard and thought, ‘A camera there'd show the hitter and pitcher,’” Cubs and White Sox Voice Jack Brickhouse said. NBC first used it on the 1957 World Series.

Color TV commenced Aug. 11, 1951: Brooklyn at Boston. In 1952, the Fall Classic debuted the novel split screen. From 1947 through 1964, the Gillette Co. sponsored the Series.

“The whole country followed it – farmers, factory workers, kids smuggling radio into class. Life stopped for the Series,” said Family Ties TV creator Gary David Goldberg.

What they saw lingers. 1954: In the Giants-Indians opener, Vic Wertz tested New York’s young center fielder. “There’s a long drive way back in center field – way back, back,” cried Brickhouse. “It is – oh, what a catch by Mays!”

The game’s greatest moments seemed to be made for the nation’s newest craze.

In 1953, ABC launched sport’s first network TV series: Dizzy Dean’s megapopular Game of the Week. In 1955, joining CBS, Game lured 80 percent of sets in use. Dean sang "The Wabash Cannonball," deemed the universe pod-nuh, and interpreted English as no one has, or is likely to. A batter “swang.” A hitter stood “confidentially at the plate.”

In 1957, CBS added a Sunday to its Saturday Game, few knowing what Ol’ Diz would say next. By 1960, three networks covered 123 games, the precursor to baseball’s current alignment with Fox, ESPN, and TBS. By contrast, in 1966 NBC bought exclusivity, making it baseball’s only network and Curt Gowdy its primary voice.

Gowdy had been Red Sox 1951-65 lead announcer. Ninth in 1966, they won an Impossible Dream last-day 1967 pennant. Two years later the even more once-awful Mets won the Series.

“Waiting is [Cleon] Jones. The Mets are the world champions!” Curt said of Baltimore’s Dave Johnson’s ninth-inning fly. Ultimately, Gowdy called 12 World Series, 15 All-Star Games, and multiple Emmy Award-winning episodes of The American Sportsman.

In 1971, the Pirates’ Roberto Clemente showed what Commissioner Bowie Kuhn called a “touch of royalty.” That Oct. 13, 60 million saw No. 21 in the first Series night game on NBC from Pittsburgh in Game 4. In 1976, ABC began to share the postseason and All-Star Game. Its Monday Night Baseball starred, among others, Bob Uecker – to partner Howard Cosell, “Mr. Baseball.”

For a long time, interest rode a magic carpet woven by the 1975 Red Sox-Reds Classic watched in all or part by more than 124 million. Carlton Fisk’s drive off Fenway’s left-field pole for a 7-6 Game 6-winning home run was immortalized by replay – something invented as early as 1959 during a game when Yankees starting pitcher Ralph Terry yielded his first hit in the ninth inning. Videotape recently had let a home team air postgame highlights. On a whim, Allen asked director Jack Murphy about reshowing the hit – the first-ever replay.

At core, instant replay fits football like a glove. “It’s an analyst’s sport,” explained NBC’s Bob Costas. “(But) conversation fills baseball’s core. Talk about the guy sitting at the end of the dugout. Is he a character? Does he give guys the hot foot?”

In baseball, technology should aid personality, as Fisk’s shot showed while he was willing his ball to the fair side of the foul pole. The mix fueled highlight series like This Week in Baseball, gracing cable TV that relied, in turn, on satellite to link systems and swell interest. In 1976, Ted Turner bought the Braves, renaming WTCG Atlanta SuperStation WTBS. In 1982, Atlanta’s big-league record 13-0 start was, said mikeman Ernie Johnson, “the ‘two-by-four’ hitting America between the eyes.” SuperStation voices rose: WOR New York’s Tim McCarver, WTBS’s Johnson and Skip Caray, and WGN’s legendary Harry Caray. “There’s a long drive!” Harry bellowed. “It might be! It could be! It is!” whereupon Middle America celebrated.

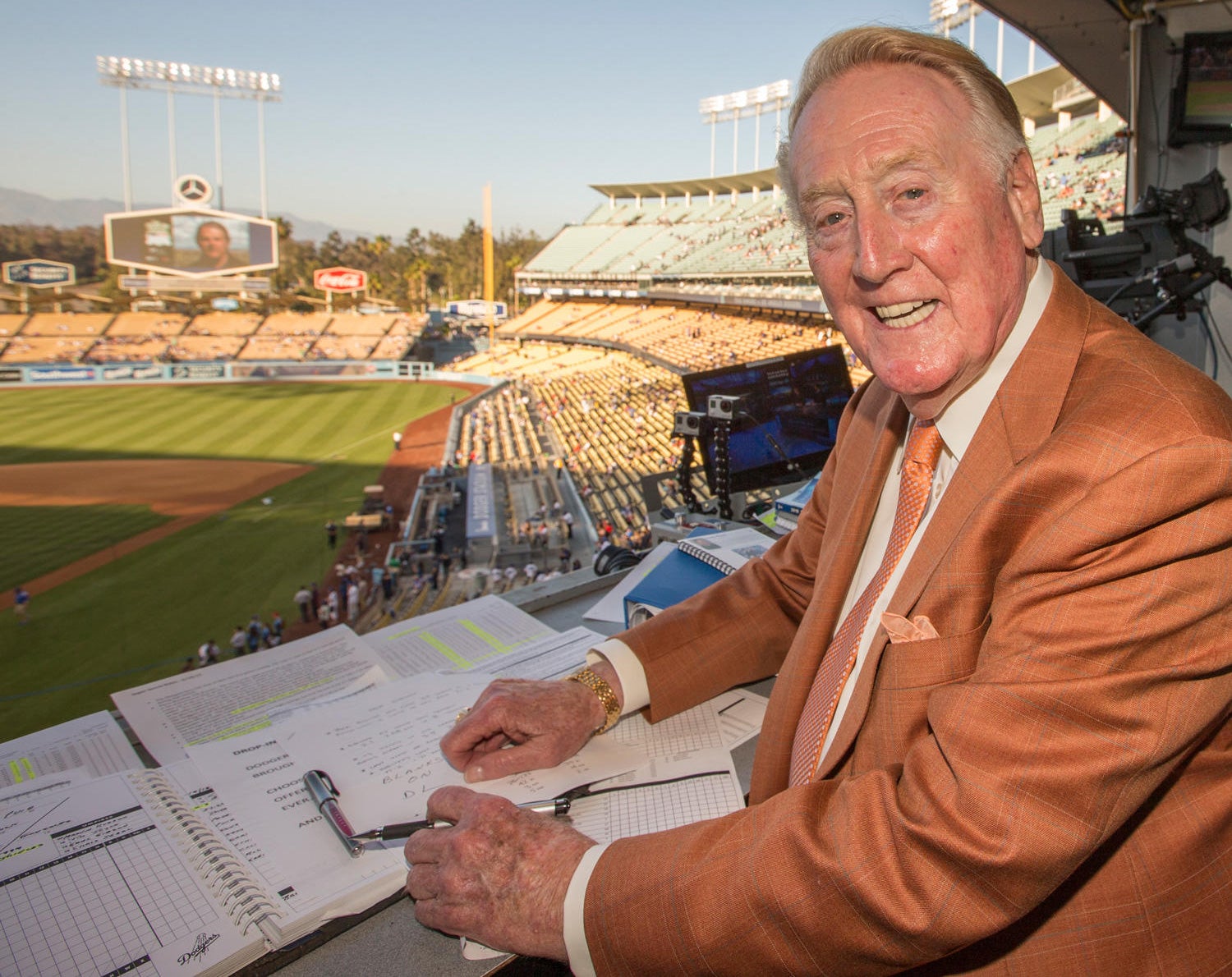

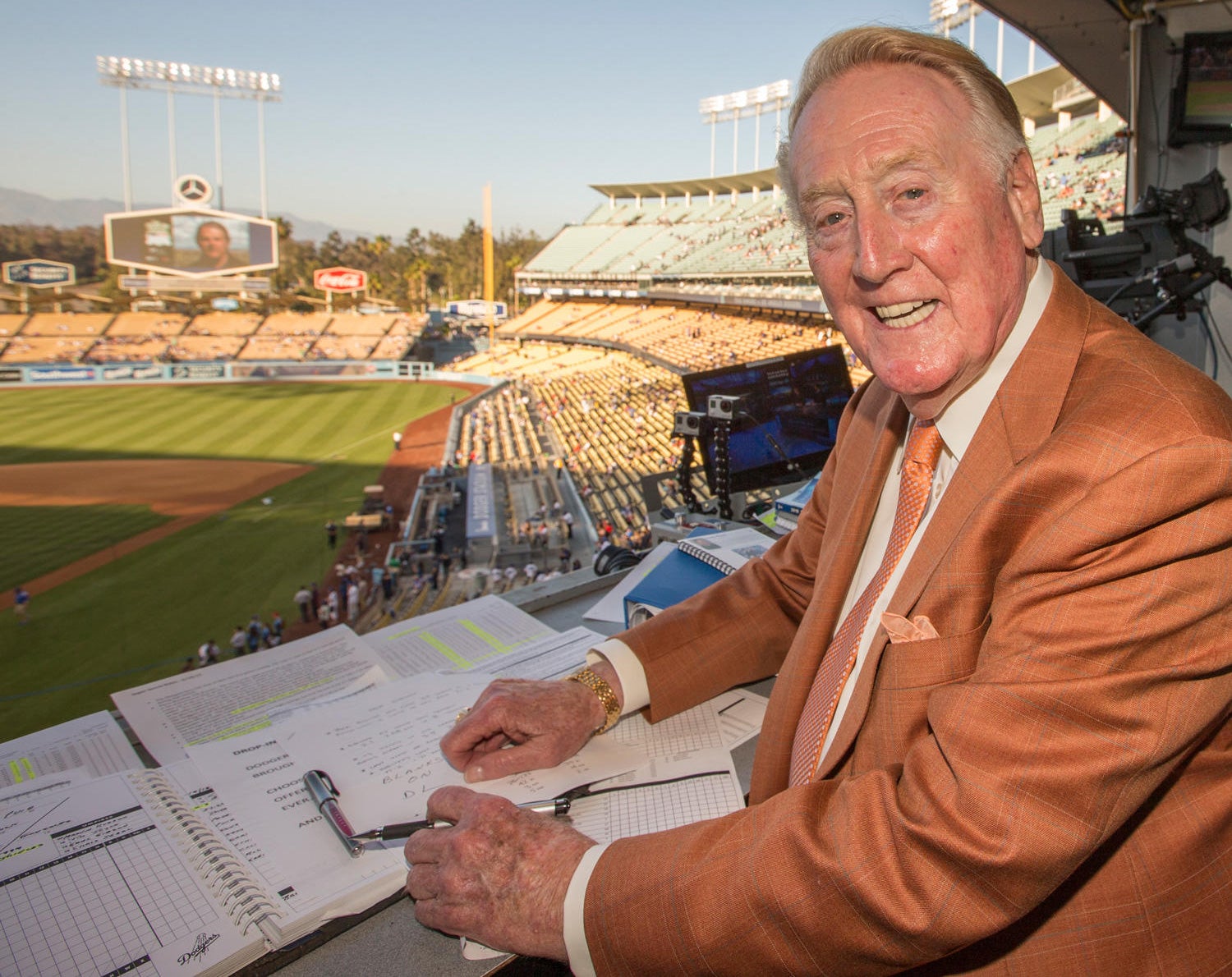

Cable’s birth eroded the network’s grip on the game, but the national broadcasters still captured America’s attention. Joe Garagiola replaced Gowdy on NBC play-by-play in 1976. Each’s analyst was Tony Kubek. In 1983, Vin Scully began play-by-play on NBC; Joe moved to analysis, and Kubek joined the backup Game’s Costas. Scully has 25 Series, 67 years of Dodgers play-by-play, a lifetime Emmy Achievement Award and the 1982 Frick Award. His history often parallels the game’s biggest moments.

Oct. 4, 1955: “Ladies and gentlemen, the Brooklyn Dodgers are the champions of the world!” April 8, 1974: Hank Aaron crossed a Ruthian line. “To the fence! It is gone!” Vin said, hushing. “A black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.” October 26, 1986: “So the [Mets] winning run is at second base,” he said in Series Game 6. “Litle roller up along first ...behind the bag …It gets through Buckner! Here comes Knight! And the Mets win it!”

Game 7 of the 1986 Series routed Monday Night Football in audience share (55 to 14 percent) and rating (38.9 to 8.8) by luring 81 million viewers – the most-watched-ever baseball game. It preceded Scully’s nonpareil call. But Scully had more to come just two years later.

Injured, L.A.’s Kirk Gibson seemed sure to miss Game 1 of the 1988 Series – until pinch-hitting in the ninth. Oakland led, 4-3, as Gibbie limped to a 3-2 count. “The game right now is at the plate … High fly ball into right field! She iiiis gone!” said Scully, stunned. Sixty-seven seconds later: “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened!”

Change, however, was inevitable. Out of the blue, CBS paid $1.04 billion for 1990-93 exclusivity. After the 1994-95 Baseball Network, Fox bought regular season coverage, sharing October’s with NBC. Fox’s Joe Buck became the Series’ youngest voice since Scully. ESPN came aboard in 1990 with five games a week, dropped to three, boasted the K Zone and first official’s replay, and launched a Sunday Night Baseball flagship.

The changes keep coming. But the fans’ love of the game on the screen remains the same.

“It’s just got everything,” former President George H.W. Bush said when asked why he loved the game.

Since 1939, televised baseball has shown us everything.

George Will said: “I write about politics, mostly to support my baseball habit.”

Due largely to TV, it is a habit hard to break.

Curt Smith is Senior Lecturer of English at the University of Rochester

Related Frick Award Winners

Related Stories

Red Barber made New York switch

Vin Scully came to Cooperstown in 1951

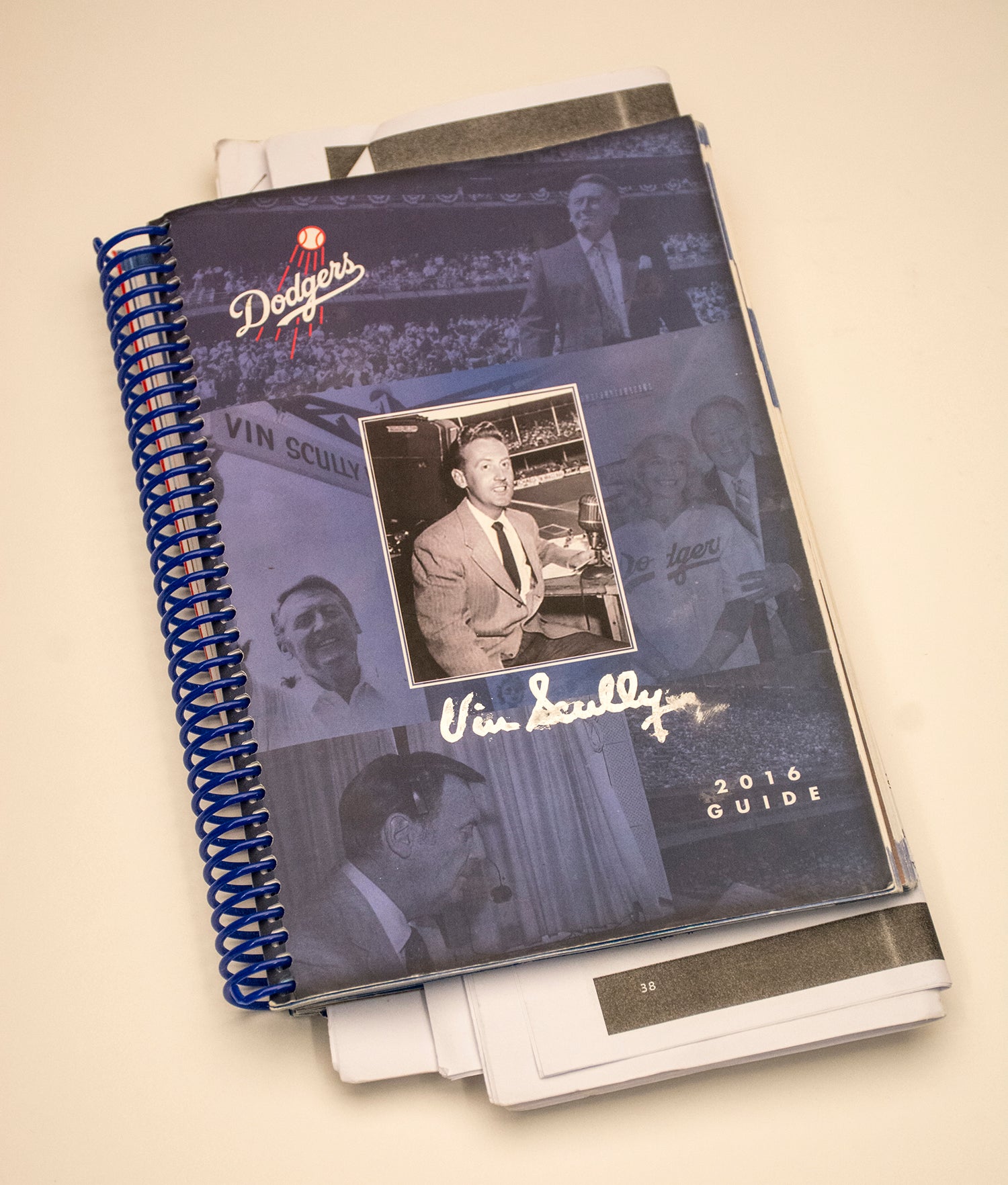

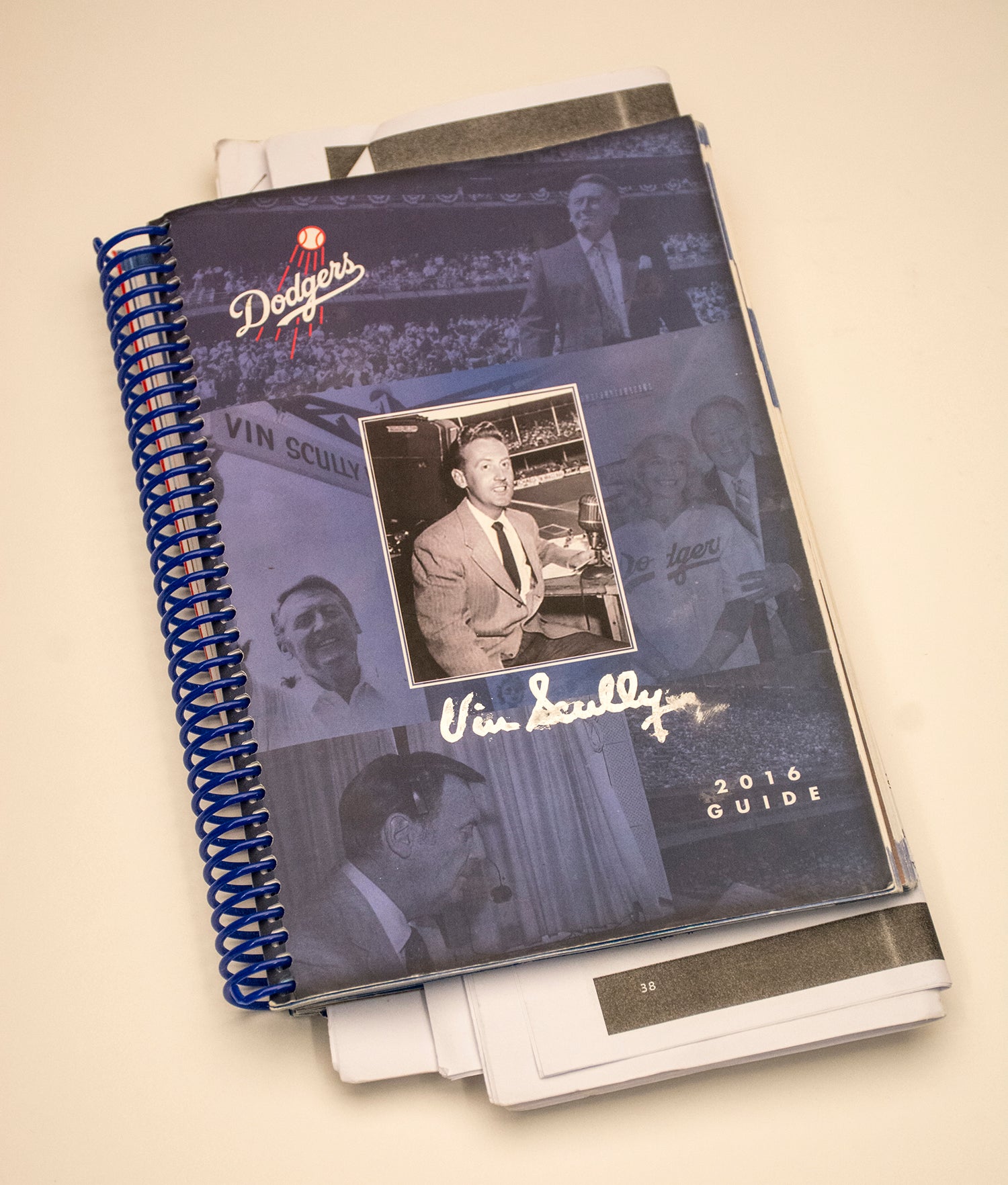

Vin Scully’s 2016 Dodgers Media Guide puts a 67-year long career into perspective

His calling: Broadcast legend and Frick Award winner Felo Ramirez saw it all

Red Barber made New York switch

Vin Scully came to Cooperstown in 1951

Vin Scully’s 2016 Dodgers Media Guide puts a 67-year long career into perspective