- Home

- Our Stories

- Skip Lockwood's Journey

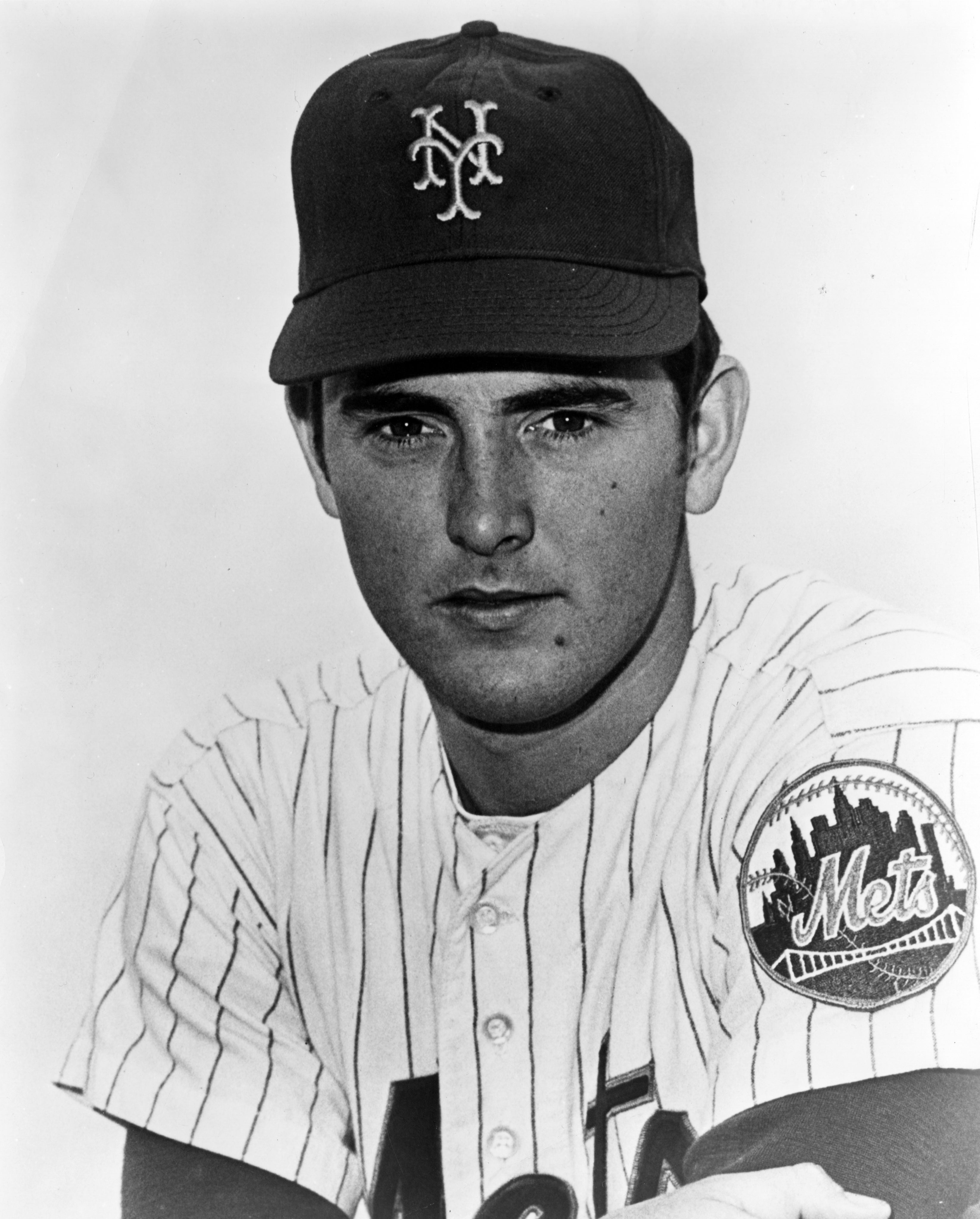

Skip Lockwood's Journey

A gifted storyteller, Skip Lockwood used his 13 years as a big league baseball player to write an insightful book on his diamond experiences as well as entertain a captivated audience during a recent speaking engagement at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

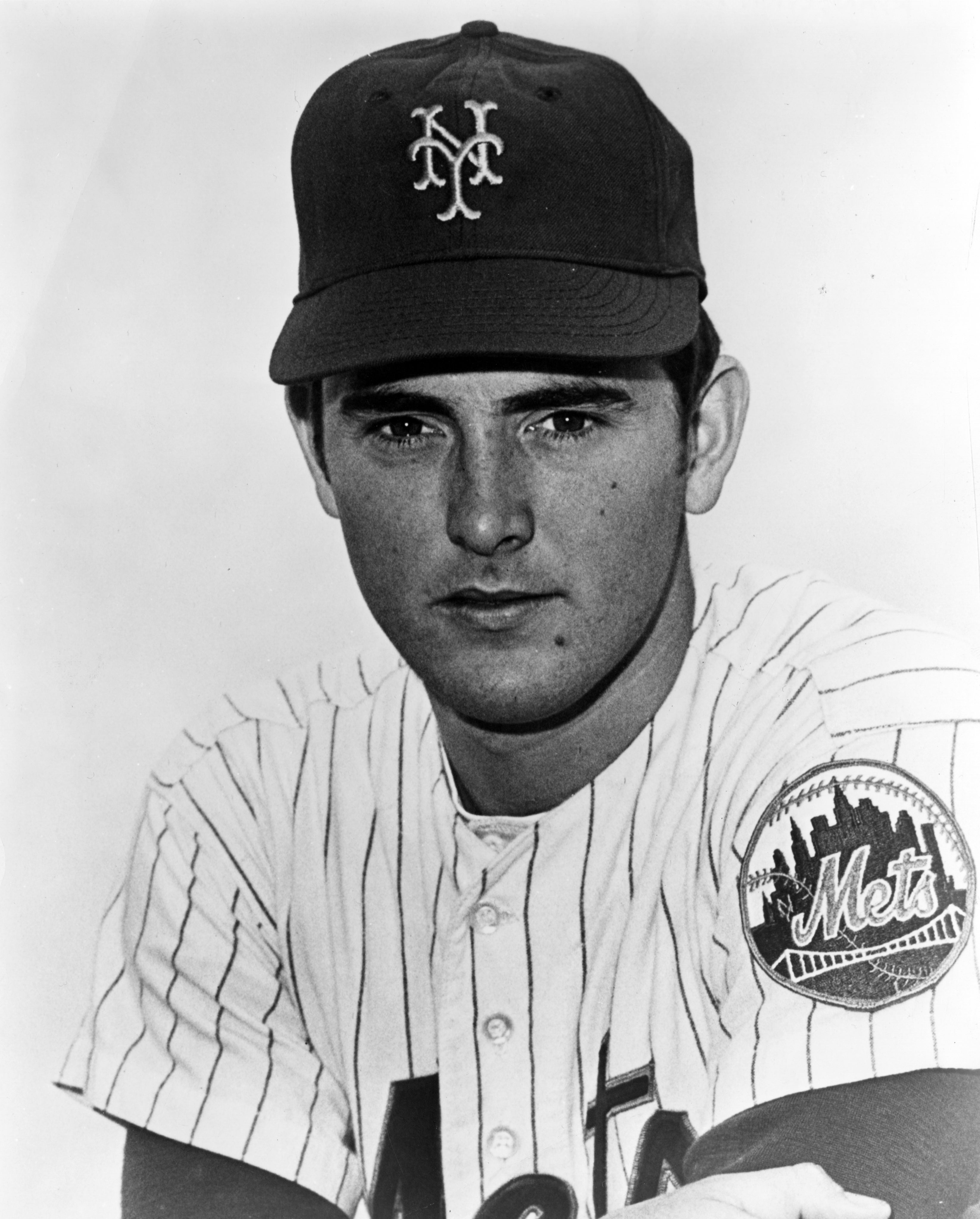

Lockwood, whose most productive seasons came as a New York Mets reliever in the late 1970s, was in Cooperstown as part of an Authors Series program held inside the Bullpen Theater on Aug. 15. After showing the crowd a glove he wore on his left hand during his playing career – it’s even included in the action shot on his new book’s cover – and his MLB lifetime pass that allows him and a guest to attend any regular season game, Lockwood shared tales included in the 2018 release, “Insight Pitch: My Life as a Major League Closer,” from a pro career that lasted from 1966 to 1981.

“I wanted to write a different book – not your standard baseball memoir,” said Lockwood in an interview before his program. “The book is more about visualization and preparation. What I would like the reader to take away is that as a metaphor for other things that you do in your life, this book can be the stepping stone to how you think about those things.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“Baseball is better if you plan for the negative and the positive,” added Lockwood, who said he wrote every word without the use of a ghostwriter. “So if you plan to strike everybody out and you go out there and the first guy walks, there goes your preparation. So you have to prepare for the game as it really occurs and what you’re going to do when things don’t go well. It’s a thoughtful approach to baseball.”

After joking the book has gotten some great reviews, even from “people without my last name,” he shared his thoughts on the Hall of Fame, a place he once visited while accompanying the Mets to a Hall of Fame Game in the ’70s.

“The Hall of Fame is a memorial to so many gifted men and women,” Lockwood said. “The guys that are here that I know, that I played with them and against them, were exceptional in their own way. It’s just amazing to see what a testimony this is.

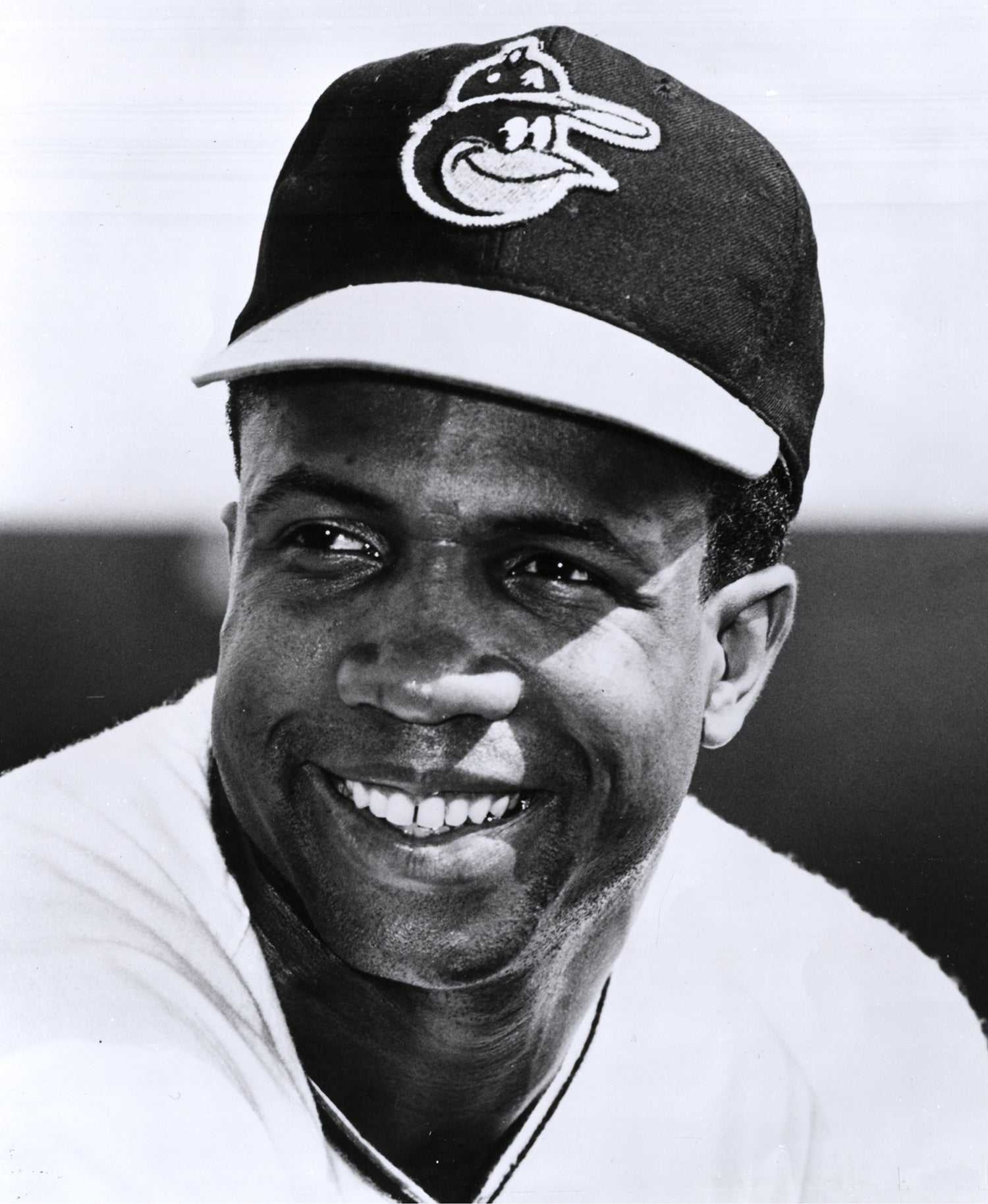

“For me, the Hall of Fame has always been something that was a goal – a little bit too far out of reach for me – but boy, when I played with guys that were going to go to the Hall of Fame you could see the difference. They were guys in the clubhouse that demanded a presence, they were guys on the field that you had to notice. Even guys in their waning years. Like when I played with Frank Robinson with the Angels, he was such a stately, eloquent figure in baseball that it was just a privilege to wear the same uniform as him.”

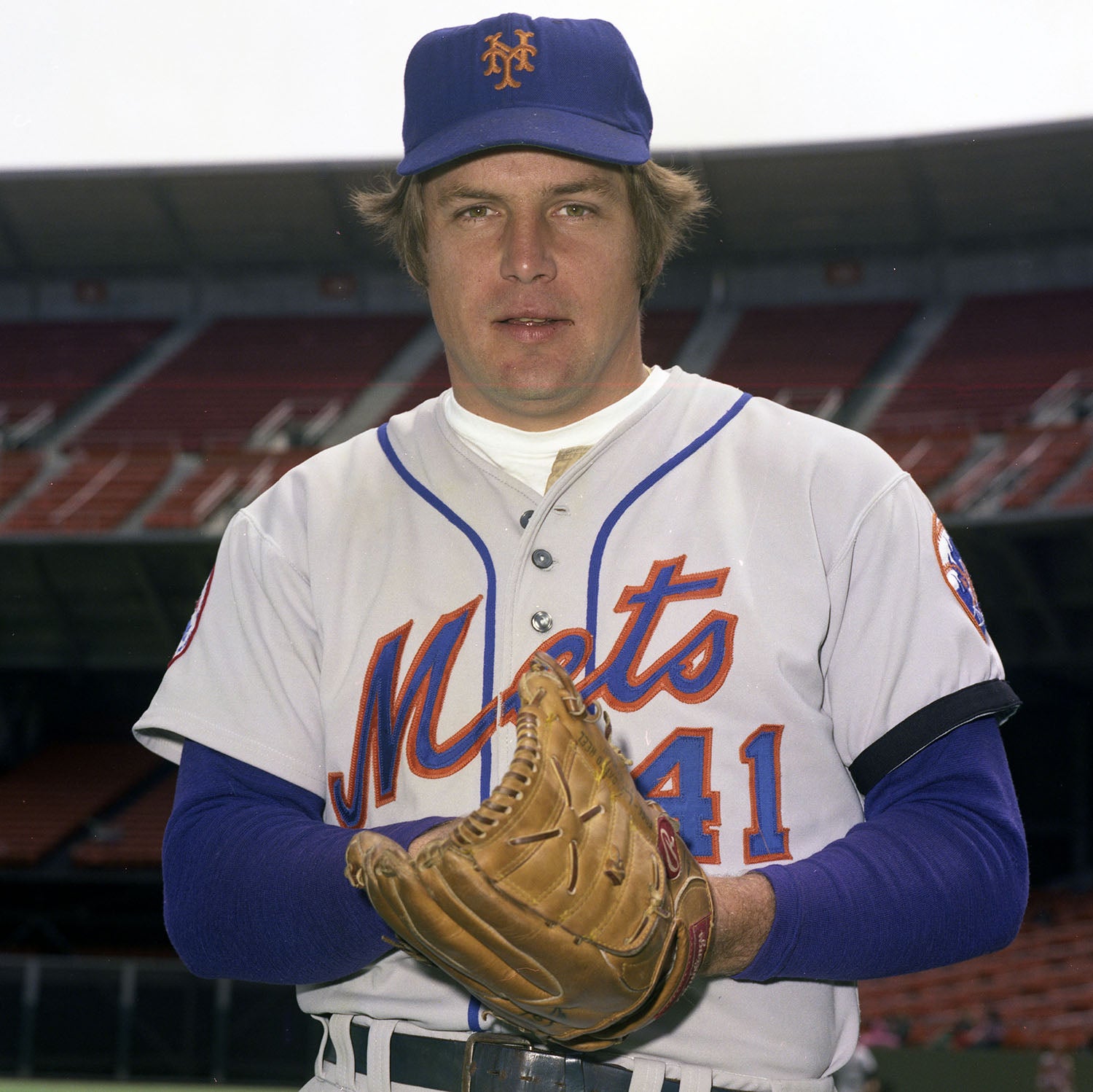

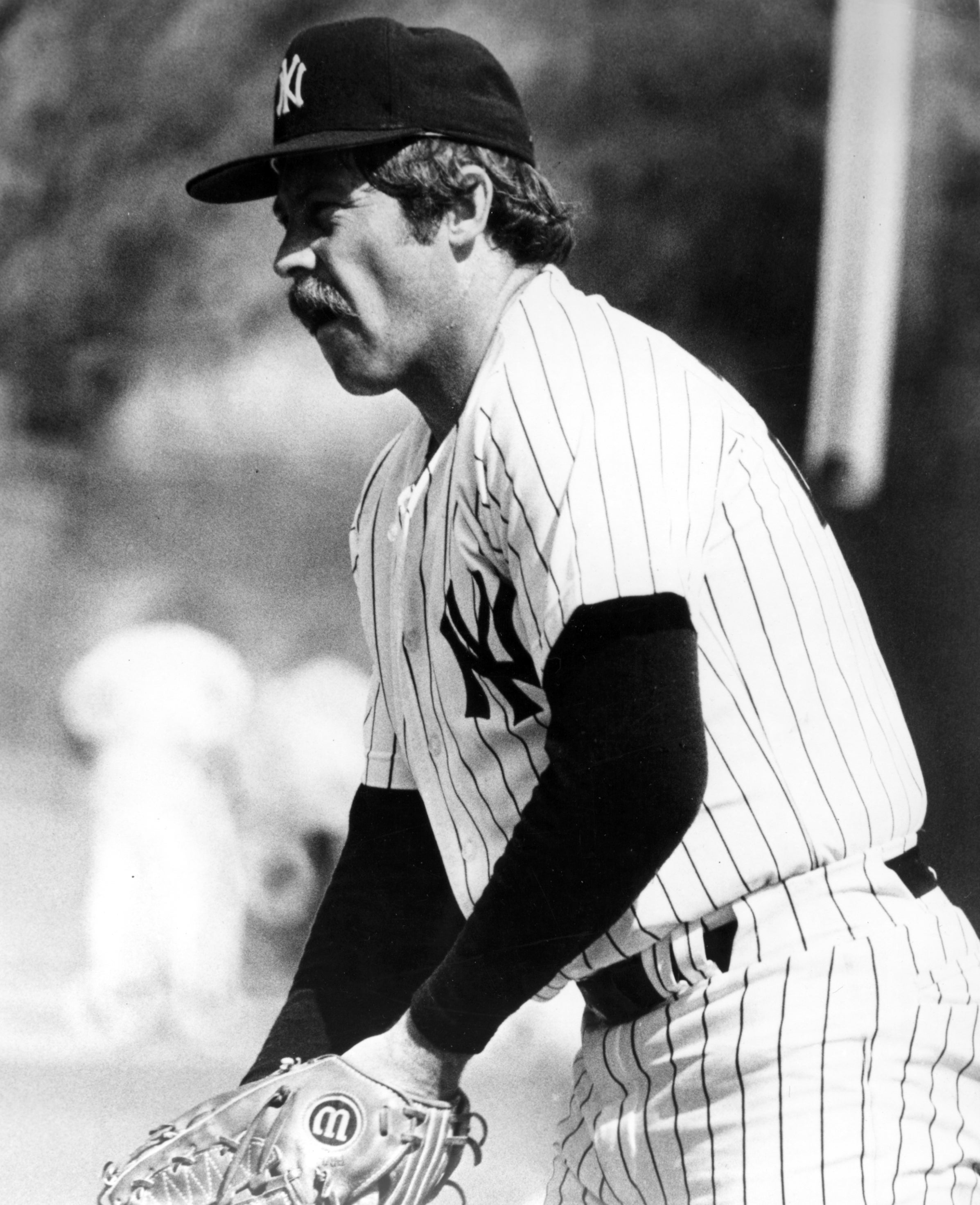

Over his career, Lockwood was also teammates with such Hall of Famers as Catfish Hunter, Carl Yastrzemski, Nolan Ryan, Tom Seaver and Carlton Fisk.

“Catfish was out of Hertford, North Carolina, just this rawboned rookie. He was my roommate in Spring Training and there couldn’t have been two more opposite people in the world: A guy from North Carolina and a guy with glasses from Boston and talked funny,” Lockwood recalled. “And it’s hard to capture exactly what Tom Seaver meant to me. He was the ‘poster boy’ for baseball in New York. His preparation for the game was different than anybody else I had ever met. He was so intense and so thorough. He had a book on hitters as to how to get them out – I didn’t even have a book. He was a guy that I tried to model myself after. And I was a veteran player at the time. To be able to change and be thoughtful in your approach and to be deliberate in what you do every day was very new for me and Tom was the architect of that for the whole team.

“Tom was, hands down, the guy that led our team.”

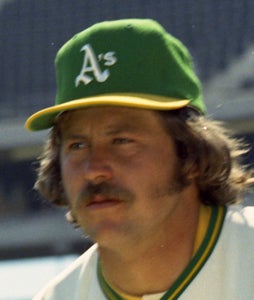

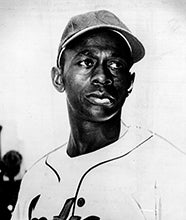

Lockwood’s rookie season was 1965, a year the then-third baseman spent with the Kansas City Athletics. Not only was Hunter on the team, but another future Hall of Famer, Satchel Page, at the reported age of 59, had a three-inning scoreless stint against the Red Sox on Sept. 25 of that year.

“He was tall and rangy - looked like somebody had left a hanger in a suit of clothes – and we lockered together that one day. I had a stool and he had a rocking chair,” Lockwood, who was only 19 on that September day, remembered. “I really didn’t know who it was until he came in and I kind of figured it out after a group of reporters came in with him. He shared story after story. I had to go out for batting practice, but I wish I would have stayed in the clubhouse and listened to all the stories.”

Because of the bonus rules then in effect, Lockwood had to stay on the big league roster for the entire 1965 season or risk being lost to another team. A third baseman at the time, he eventually made the successful transition to starting pitcher and then closer.

“I wasn’t a great hitter in pro ball, but I was a great hitter in high school because all they had was fastballs and I could hit those. I came out of the service and back to trying to be a third baseman, but it just wasn’t there. Once they find out you can’t hit a curve that’s all you see,” Lockwood said. “Charley Finley (owner of the Athletics) bailed me out and gave me a job as a pitcher.

“There were a lot of things about being a starting pitcher that I loved, but I didn’t like waiting two or three days to have to pitch again. It wasn’t the exact right fit for me. So when I got a chance to be a relief pitcher and then the closer, that was a good fit.”

According to Lockwood, his pitching repertoire consisted mainly of a single pitch.

“I’ll tell you exactly what I told catcher John Stearns the first day I got to the Mets. He said, ‘What do you throw?’ and I said, “I throw a fastball.’ He said, ‘Okay, I’m still listening,’ and I said, ‘You heard it. I throw a fastball,’” Lockwood said.

“I had a little curve ball, but it was a ‘show you’ pitch. I went out there on a wing and a prayer with those two pitches and it doesn’t take long for the batters to figure it out.”

Lockwood, who has been pitching with an injured right arm for some time, saw his big league career come to an end in April 1981 when the Massachusetts native was released by his hometown Red Sox.

“The therapy for a hurt arm back then was you try and throw and if it hurts you wait a week. So I spent a whole half season doing that, hoping that it was going to be better. So when the Red Sox signed me I still didn’t know whether or not I could get back up to speed with the fastball,” he said. “As it turns out there was some sort of pinched nerve in the shoulder. I could get it to home plate, but I didn’t have that extra that I needed.

“Today, I think they could fix it and I could pitch 10 days later. It proved to be the ending of my career and I did it in front of my hometown fans in Boston, which was kind of embarrassing.”

In summing up his major league career, which ended with a 57-97 record, a 3.55 ERA and 68 saves, Lockwood said he had a few regrets.

“I played with intensity. Maybe too much intensity. I felt that my role in the game was to be better than the last pitcher that they just took out. Throw harder, be more aggressive. But in order to do that you have to really lather yourself up. I wish I had relaxed more and smelled the roses because it ends awfully quickly,” he said. “So I remember my career as fast and furious, but I’m glad I had the years that I had and very pleased it lasted as long as it did.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Tom Seaver strikes out 10 straight Padres

Seaver, Ryan combine for 26 Ks in sweep of Padres

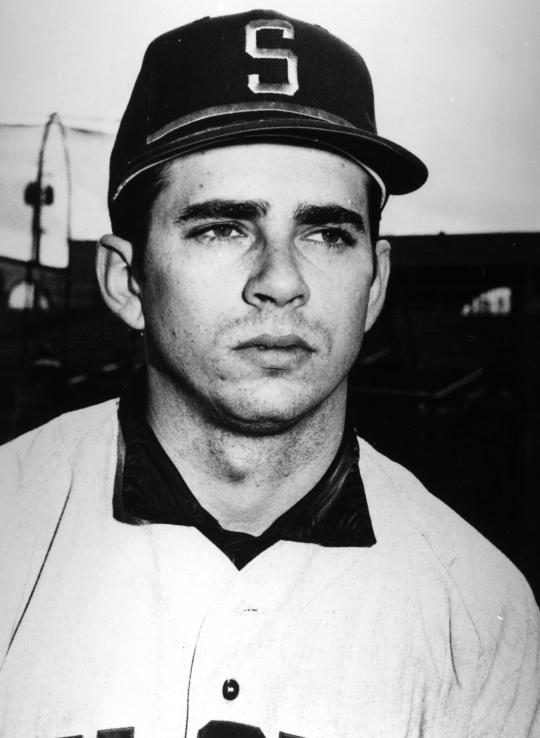

Satchel Paige pitches for A’s at age 59

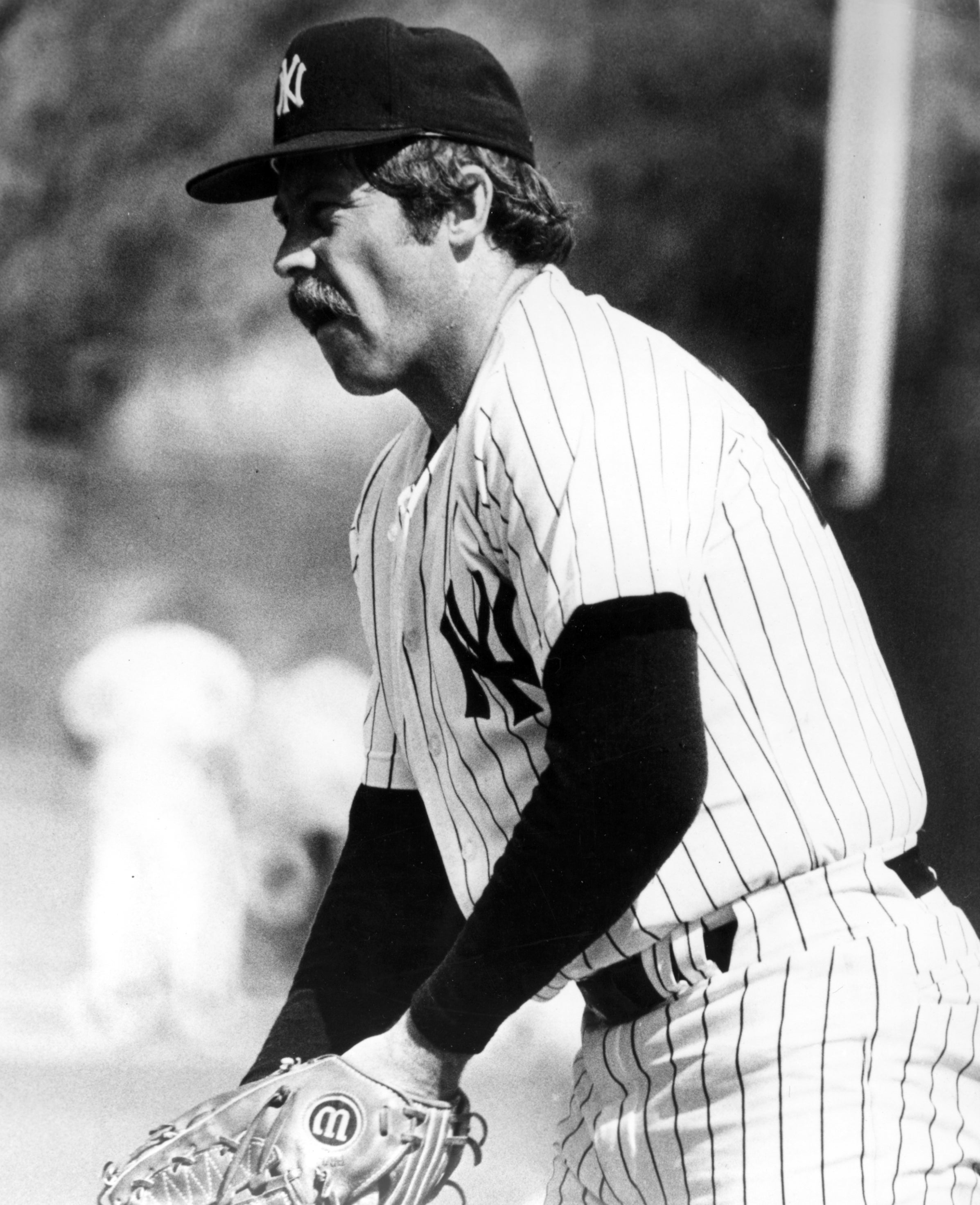

Catfish Hunter signs free agent contract with New York Yankees

Tom Seaver strikes out 10 straight Padres

Seaver, Ryan combine for 26 Ks in sweep of Padres

Satchel Paige pitches for A’s at age 59