- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Rapid Robert at the bat

#Shortstops: Rapid Robert at the bat

Bob Feller knew pitching. But his ability with a bat was, to be kind, less than Hall of Fame-worthy.

But thanks to a recent donation to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, “Rapid Robert” shares with a bat manufacturer his thoughts on bats and batting. The undated missive – typewritten, two pages in length, and on “Hilton Hotels Corporation” letterhead – is a rough draft addressed to longtime Hillerich & Bradsby Company executive Jack McGrath.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Hillerich & Bradsby, manufacturer of the famed Louisville Slugger bats, began turning bats for big leaguers in 1884. McGrath, who worked as a vice president of advertising, promotions and public relations for 48 years, died at the age of 79 in 1987.

Feller’s eight-paragraph correspondence with McGrath begins with his own youthful memories.

“I do know that my first bat was a pre-Little League Louisville Slugger and was painted green with tape on the handle,” Feller most likely dictated to a secretary. “I also planed bats on the farm in Iowa out of hickory and, of course, they weighed a ton.”

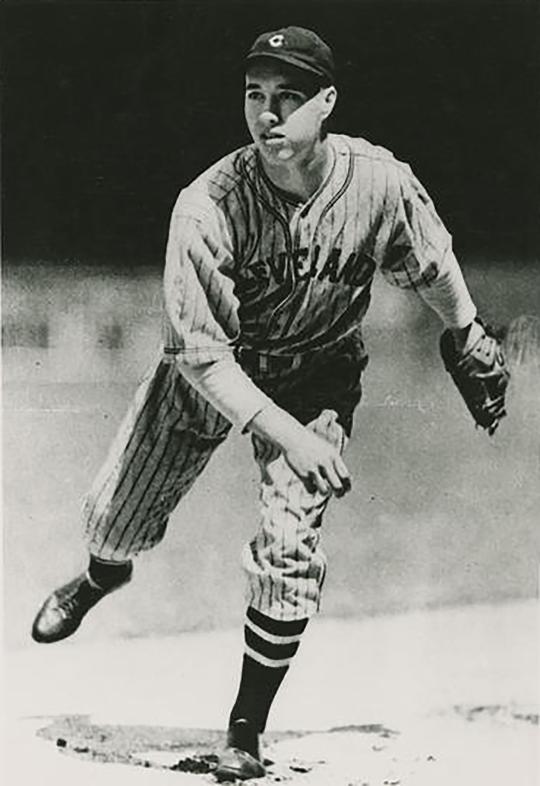

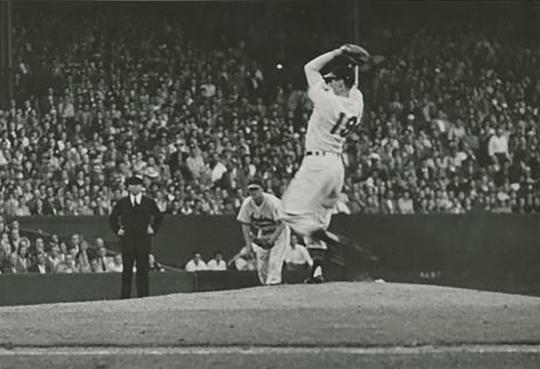

Feller’s mound accomplishments as a Cleveland Indians pitcher are legendary – including fanning 17 batters in one game at the age of 17, tossing three no-hitters and 12 one-hitters, and leading the league in strikeouts seven times despite losing almost four years in his prime due to military service. After ending his 18-year big league career with 266 victories and 2,581 strikeouts, Feller would be elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962.

But, as Feller readily admits, his career as a batsman was lacking, compiling a career batting average of only .151 (193-for-1,282) with eight home runs and 99 RBI.

“I did not sign a contract with Hillerich & Bradsby until I had been in the big leagues two or three years,” Feller said. “Of course, I’ve known many of your representatives throughout the years … and always enjoyed their personal concern … even though I was of no value to your company as a slugger or personality in promoting your bats.”

Feller then in the letter portrays his unique observation skills as a pitcher, explaining, with a bit of humor tossed in, how from the mound his certain insights would allow him an advantage.

“Of course,” Feller said, “I always checked the type of bats the opposition used, whether they are heavy, light, how the weight was distributed, and most important, did they have a thick or thin handle, which would affect somewhat the way I would pitch to them.

“About the most interesting and generally unknown fact about baseball bats and hitters in relation with pitchers is that in order to hit a fastball pitcher a batter should use a heavy bat and to hit a curveball or breaking ball pitcher a batter should use a light bat.”

“However, if a pitcher has both an overpowering fastball and a sharp curve then I presume a batter would use a medium weight club even though he would probably prefer to use a light bat and a heavy bat together on each swing, but the rules don’t permit that … If you think I’m being a little facetious you are absolutely correct.”

According to Hall of Fame Librarian Jim Gates, “Documents like this show why these small artifacts are important to save. They not only are an insight into the thought process and mindset – before analytics – of a great pitcher like Bob Feller, but they also document how correspondence once worked.”

The letter in question was donated to the Hall of Fame earlier this year by Richard Koloda of Wayland, Ohio.

“I found it when I was cleaning out my late brother's house in Seven Hills, Ohio, among some family papers,” wrote Koloda in a recent email. “My mother, Ruth, worked for Bob Feller (I assume his insurance agency) sometime in the 1970s. I remember her getting signed photos of Bob for us.

“As for donating it, I believe as Indiana Jones would say, ‘It belongs in a museum.’ And if I held on to it, my daughter would likely throw it out, as she never heard of Bob Feller.”

Feller, who had been in the insurance business since he retired from baseball in 1956, began working for Cleveland’s Sheraton Hotel in 1969. He would later work for Hilton Hotel in Cleveland as Director of Sales-Sports.

The longtime Indians star, who passed away in 2010 at the age of 92, ends the letter with a rousing celebration of the National Pastime.

“A baseball bat and a ball,” he said, “are the two most essential items in the American sports scene and have furnished millions of baseball fans with thousands of thrills throughout the history of baseball.

“And if baseball is dying, if anyone alive today should have the privilege of living long enough to be invited to baseball’s funeral, they no doubt would have outlived Methuselah by 2,000 years.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

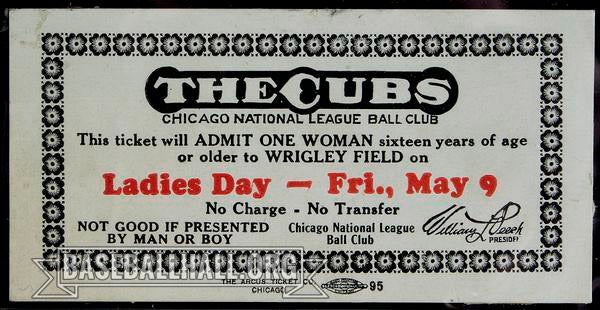

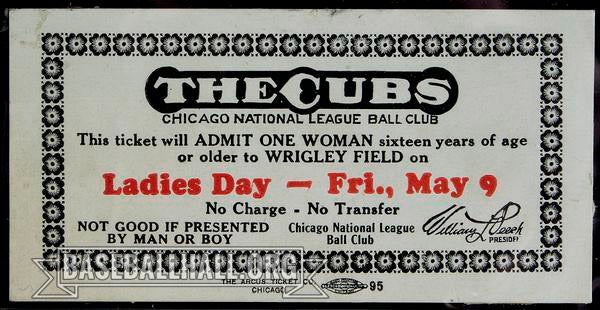

#Shortstops: Ladies Day promotions gave women the chance to cheer

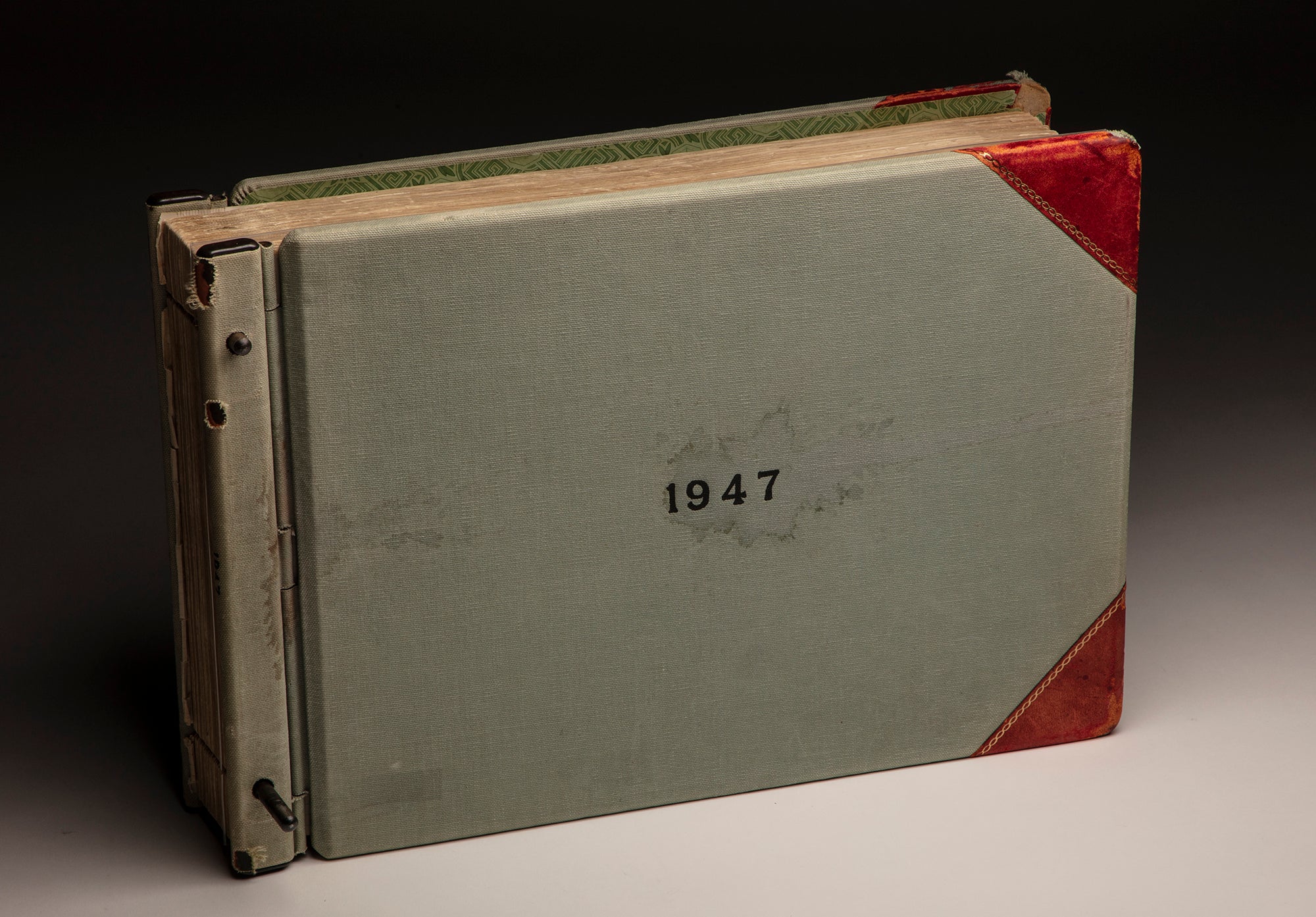

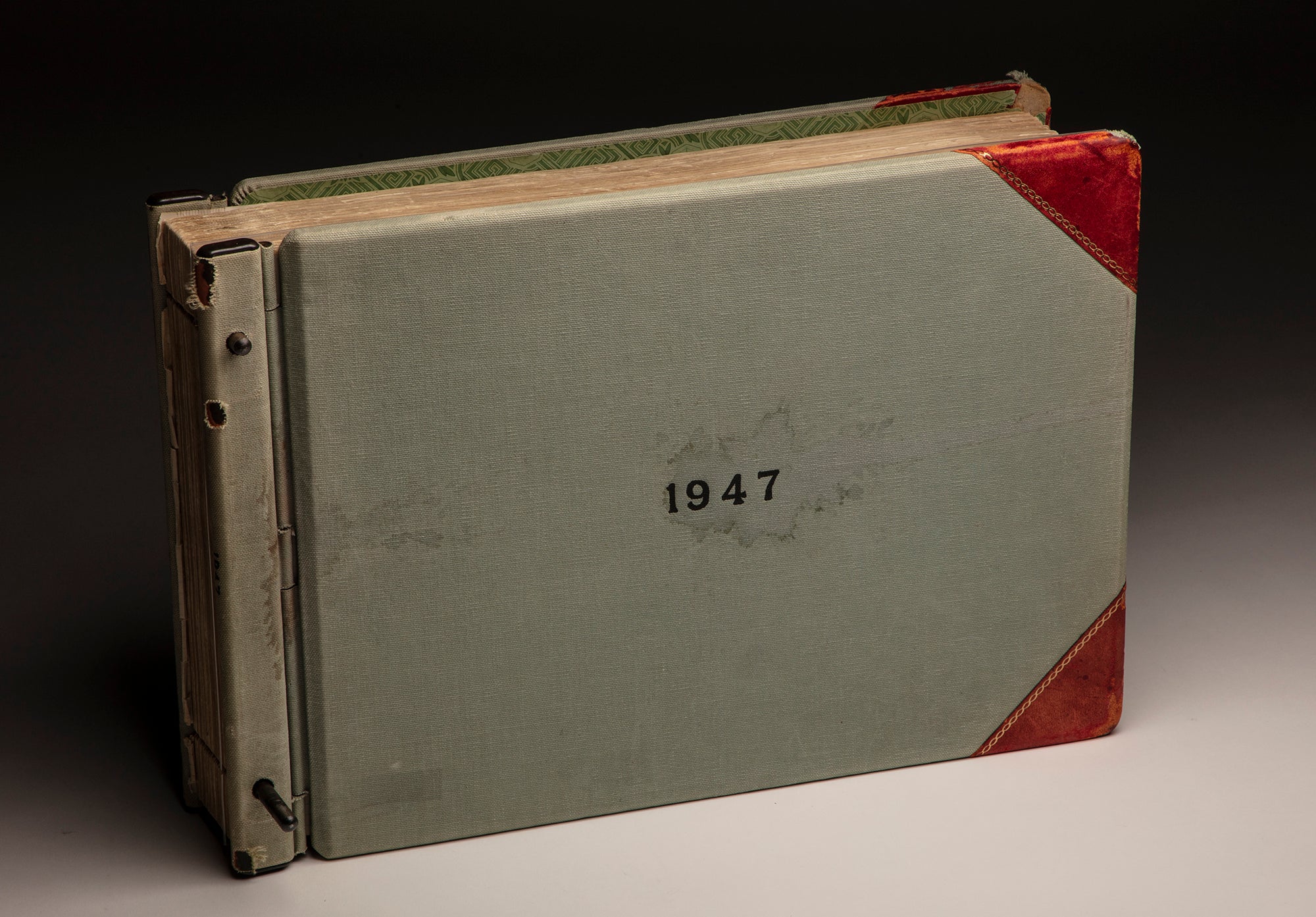

#Shortstops: A Page in Time

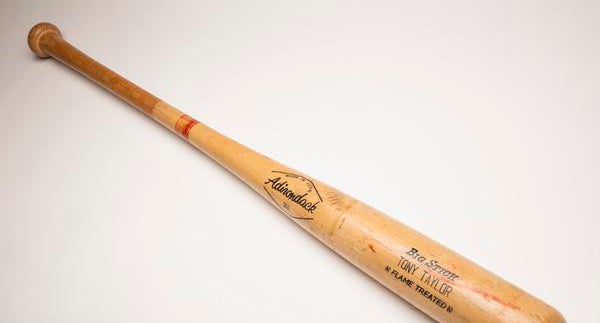

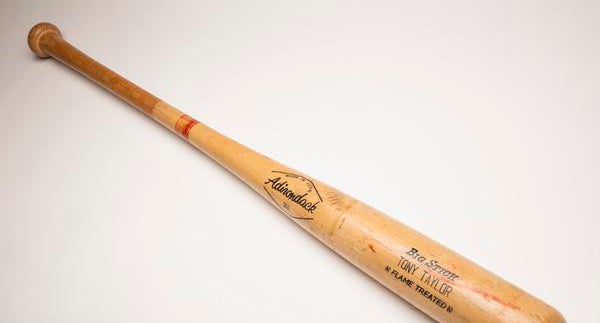

#Shortstops: Borrowed bat provides power for Schmidt

#Shortstops: His 'Airness’ Takes on Baseball

#Shortstops: Ladies Day promotions gave women the chance to cheer

#Shortstops: A Page in Time

#Shortstops: Borrowed bat provides power for Schmidt