- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Gehrig’s legacy shined bright in Normandy

#Shortstops: Gehrig’s legacy shined bright in Normandy

Lou Gehrig’s legacy far outlasted his lifespan. And 75 years ago. Gehrig’s ongoing heritage allowed him to be a part of a major turning point in World War II.

The D-Day invasion of northern France, which took place on June 6, 1944, had 160,000 Allied troops – including future Hall of Famers Yogi Berra and Leon Day – secure the landing on the Normandy beaches. With the French coastline heavily fortified by Nazi Germany, more than 9,000 Allied soldiers were killed or wounded. But their sacrifice allowed the Allies a foothold in Europe.

Seventeen months earlier, Christine Gehrig, the mother of the late star first baseman with the New York Yankees, was christening the Liberty ship “Lou Gehrig.” The ceremony took place at the South Portland (Maine) Shipbuilding Corporation on Sunday, Jan. 17, 1943.

“It was the finest tribute ever paid my son,” said Christine Gehrig after she had cracked a champagne bottle attached to a small wooden baseball bat – a devise designed by the shipyard workers – against the bow of the S.S. Lou Gehrig.

Today, that christening bottle is one of more than 40,000 three-dimensional artifacts in the permanent collection of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

The green glass champagne bottle, with gold foil still at its top, tied at its neck with red and blue ribbon, and surrounded by a mesh covering, and situated inside a carved-out bat barrel, measures 25 inches in total. It is supported by a wooden base with an engraved plate that reads, "Christening Bottle / S.S. Lou Gehrig / Mrs. Christine Gehrig / Mother of the late Lou Gehrig / Sponsor / Launched January 17, 1943 / South Portland Ship Building Corporation / West Yard, South Portland Maine.”

Soon after Christine Gehrig passed away in March 1954 at the age of 72, her attorney announced that she had willed all her trophies and awards received by her late son, including the christening bottle, to the Hall of Fame.

Lou Gehrig – elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939 - tragically died at age 37 on June 2, 1941, the result of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). A film based on his life, “The Pride of the Yankees,” was released in 1942.

But how did Lou Gehrig’s name appear on this particular vessel?

A contest was announced for New York State schools to see how much scrap a student body could gather per person of their high school population. The contest ran for two weeks, from Oct. 16 to Oct 30, 1942. Children who collected scrap in the school salvage program were invited to name Liberty ships for the outstanding figures of their states.

While Kansas schoolchildren chose aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart, Texas schoolchildren picked Bigfoot Wallace, a famous Texas Ranger, and Minnesota schoolchildren selected the Mayo Brothers, founders of the Mayo Clinic, New York’s schoolchildren went with baseball great Lou Gehrig.

Gehrig was the second baseball figure, after Christy Mathewson, to have a Liberty ship named in his honor. John McGraw would become the third in September 1943.

The United States – which entered WWII after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 – would mass produce more than 2,700 Liberty ships between 1941 and 1945. The 10,500-ton cargo vessels were 440 feet long and 56 feet wide. The first was christened Patrick Henry.

“The career of this great American,” said New York State Education Commissioner George D. Stoddard, “has been a challenge and an inspiration to our youth. His skill at first base without a miss for a total of 2,130 consecutive games over a 14-year period created a new impulse among all sports-loving youth.

“Our young people were quick to recognize, however, that Lou Gehrig was more than a professional athlete. Studious and of high character, he took a deep interest in the welfare of youth. His magnificent determination to carry on in the face of ill health and his courage in overcoming the ravages of disease will always be remembered as the mark of a great sportsman.”

A total of 221 New York State schools participated in the salvage campaign and collected 23,688,074 pounds of scrap. Lou Gehrig was chosen out of the more than 600 names submitted of New Yorkers no longer living. The Lake Pleasant Central Rural School students had final choice by turning in the largest amount of scrap per pupil.

This came before “The Spirit of Lou Gehrig,” a fully equipped Army field ambulance, was purchased with $2,000 raised by students at the High School of Commerce and presented to the Army in January 1944. Gehrig was a Commerce graduate.

When it came time to launch the S.S. Lou Gehrig, Christine Gehrig was accompanied to Maine by a trio of high school students representing the top schools in the recent salvage campaign.

From Lake Pleasant was Vernon Yennard, 16, from the New York champ in scrap collections with approximately 119 tons of scrap – an average of 2,791 pounds of salvage per student. Hartwick High School, the second-place finisher, averaged 2,368 pounds of salvage per student, was represented by 15-year-old Norman R. Jensen; while third-place Mountaindale Central Rural School, represented by 16-year-old Leo Tansky, averaged 1,406 pounds of salvage per student.

Hartwick High School, which consolidated with Cooperstown High School beginning in the 1957-58 school year, is only seven miles from the Baseball Hall of Fame.

The Jan. 17, 1943 morning launching in South Portland, Maine, of the S.S. Lou Gehrig was set for 9:35 a.m. – based on high tide – and the shipyard stopped operations to hear the brief addresses over a loudspeaker system before the painted-gray ship splashed into Portland Harbor.

The three students were introduced to the assembled workers by H. Perry Smith of the New York State Salvage Commission, who described Gehrig’s career as a “challenge and inspiration to the youth of the country.”

Yennard, speaking for his Lake Pleasant classmates who had picked him as their representative, said, “In our collection of scrap metal, victory and peace were our motivating factors. If we have done anything, we consider it a duty to our country and we are extremely pleased to take part in the launching of the Liberty ship, the Lou Gehrig.”

South Portland Shipbuilding Corporation President Chester L. Churchill, who said that Gehrig “was a fighter who played to win, and we must be fighters and we must play to win,” added that the school scrap metal drive in New York had brought enough metal for 3 ½ boats the size of the S.S. Lou Gehrig. The S.S. Lou Gehrig skipper, Capt. John J. Dougherty, expressed hope that the ship would prove as “indestructible as Lou was.”

The Sporting News, considered at the time as “The Bible of Baseball,” editorialized in its Jan. 28, 1943 issue the appropriateness of naming a Liberty ship after Lou Gehrig.

“As Gehrig represented youth at its best, it was particularly fitting that his name should be suggested for a ship by youngsters from a rural school in New York State, who gained that privilege because of their activity in collecting scrap to help the war effort,” it read. “As Lou himself would have felt he was highly honored, could he have known the esteem and patriotism which furnished the basis for the selection. It proves the extent of the first baseman’s influence on young America.

“The game is proud to have produced such men and appreciative of the fact that, while they are not here to serve today, their ideals go marching on and their names still mean something in this service to their country.”

The S.S. Lou Gehrig was later included in “Operation Neptune,” a part of the D-Day invasion of France by the Allied forces. It carried 480 men and 120 vehicles, landing in Normandy on June 19, Gehrig’s birthday.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Trophy Gehrig presented his mother a part of Museum collection

Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium

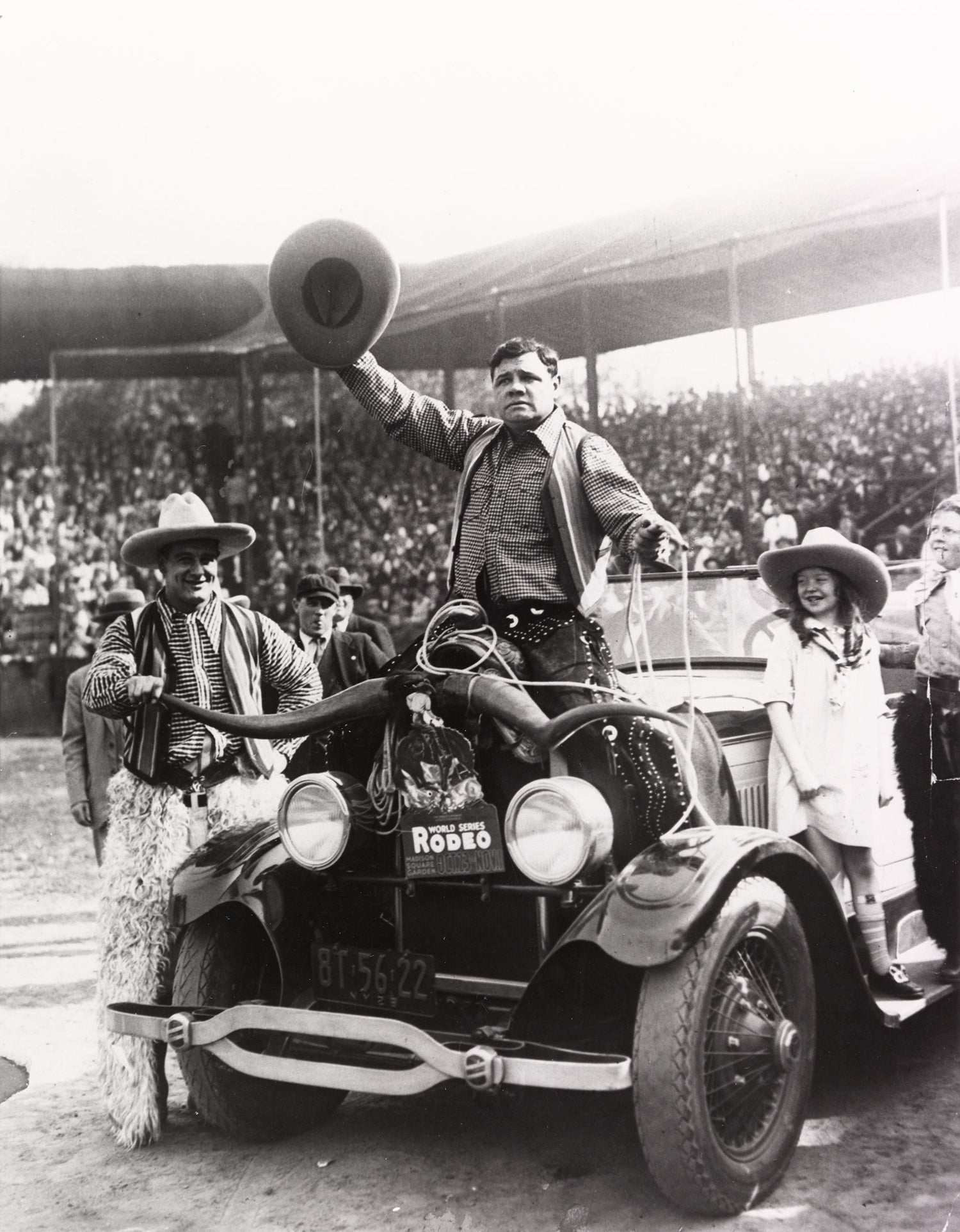

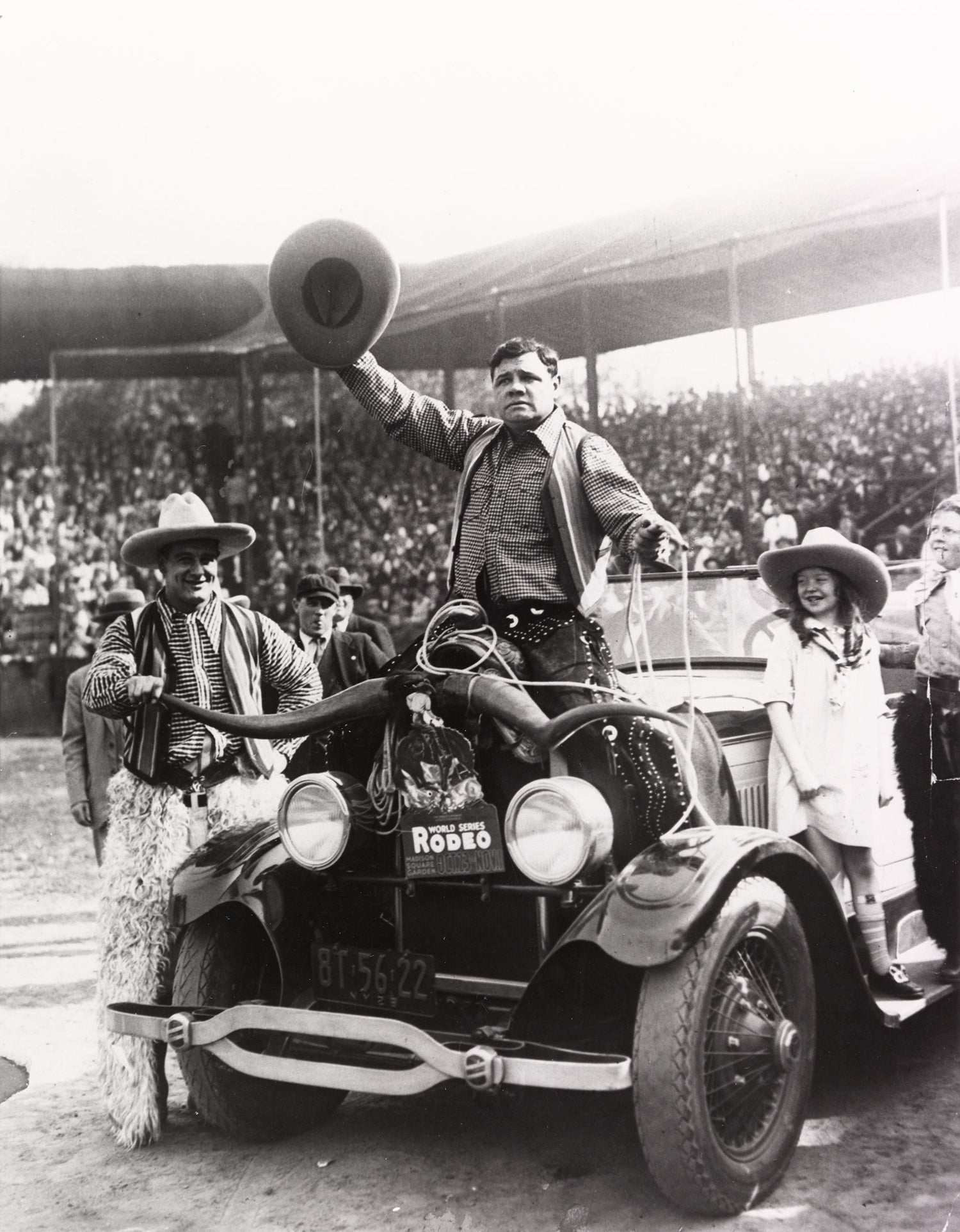

Gehrig, Ruth round up funds for NYC hospital

#Shortstops: Lou Gehrig’s gift

Trophy Gehrig presented his mother a part of Museum collection

Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium

Gehrig, Ruth round up funds for NYC hospital