- Home

- Our Stories

- Innovations that debuted in Spring Training

Innovations that debuted in Spring Training

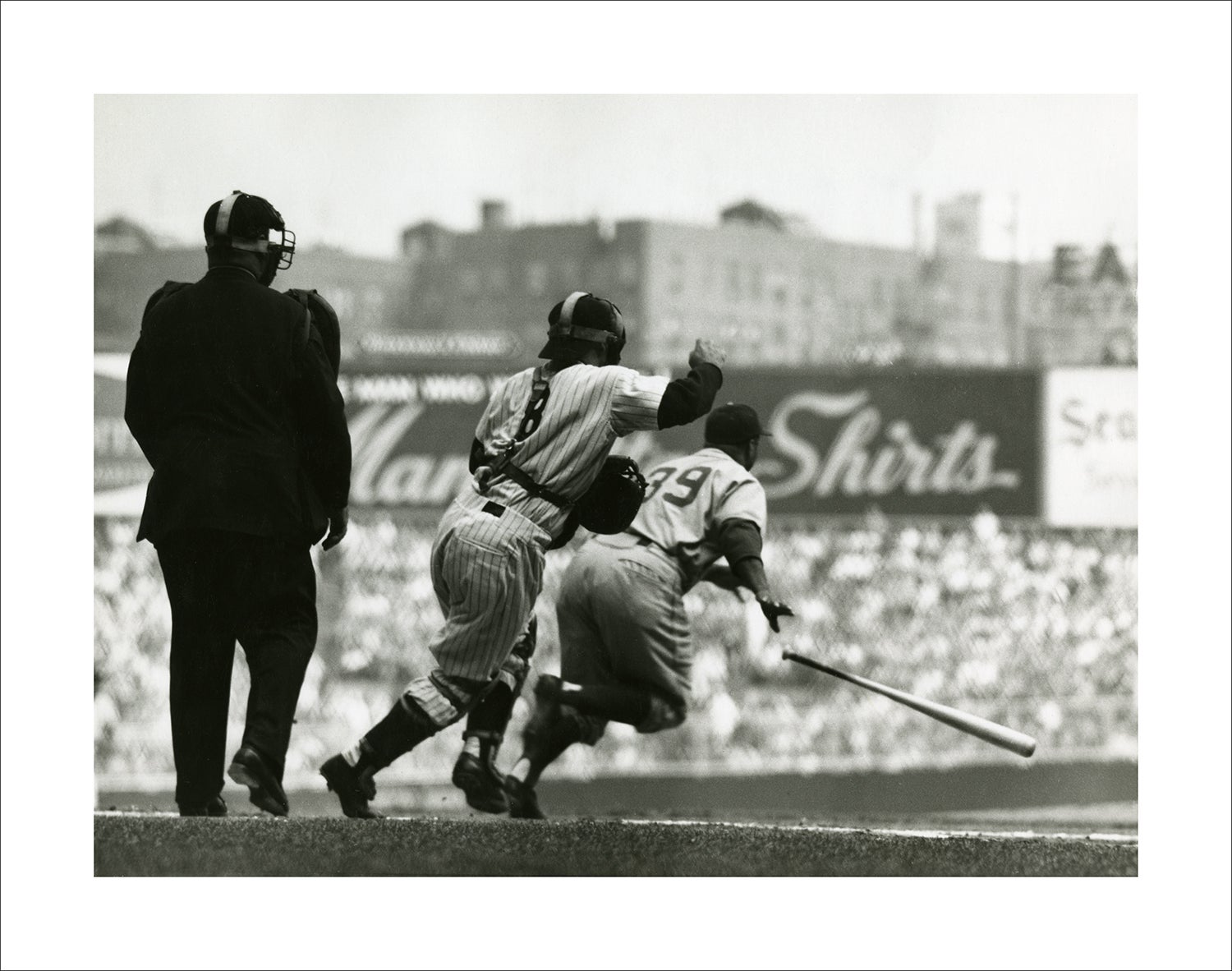

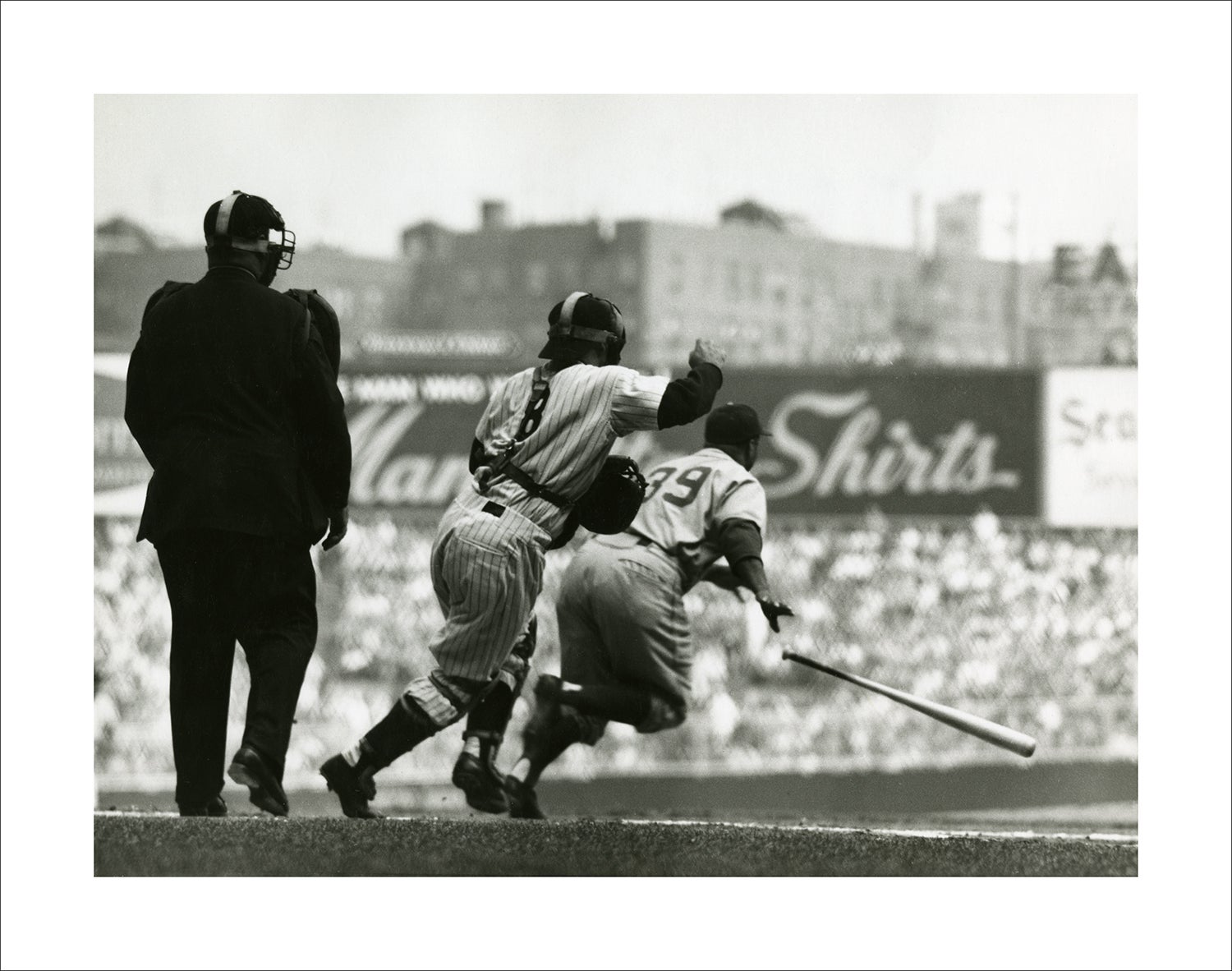

When future Hall of Famers Joe Medwick and Pee Wee Reese each came to bat wearing a special caps on March 8, 1941, the accounts from that Spring Training game in Havana, Cuba, drew notice from newspapers around the country.

Today, it would be news – not to mention a rules violation – if a player did not wear protective headgear during an MLB game. But in 1941, a Spring Training innovation changed the National Pastime forever.

On that day, the Dodgers were playing the Cleveland Indians in Havana, Brooklyn’s spring home as it prepared for the coming regular season. While it remained unnoticed by fans in the stands, Brooklyn stalwarts Reese and Medwick each faced the opposing Cleveland pitcher with a “Brooklyn Safety Cap” atop his head.

Reform often comes slowly in baseball, and for generations there was powerful resistance to any form of head protection in the National Pastime. Though players were reluctant, occasional forms of batting helmets would appear over the decades, dating back to the 19th century, but were short-lived and soon abandoned. Previous protective head devices were often disregarded as too bulky, cumbersome and unsightly.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

But by the spring of 1941, the Dodgers, at the behest their red-headed president, Larry MacPhail, had seen enough. Because Reese and Medwick had suffered devastating beanings the previous year, the visionary who had brought night baseball games to the big leagues in 1935 now wanted his player investment protected with skull insurance.

“Both Pee Wee and Joe pronounced the helmets 100 percent okay,” MacPhail said. “If these helmets had been compulsory last year, we wouldn’t have lost Reese, Medwick or (Hugh) Casey by beanings.”

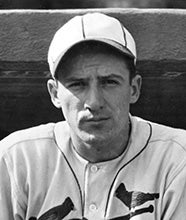

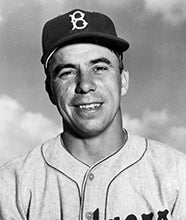

In 1940, Reese, a 21-year-old rookie shortstop with Brooklyn, was hit by Chicago Cubs righty Jake Mooty and had to spend two weeks in the hospital, while Medwick, recently acquired from the Cardinals for four players and $125,000, was later was beaned by the Cardinals’ Bob Bowman and was bothered by double vision for the remainder of the season.

“I never thought anyone could hit me in the head,” said Reese, who lost sight of the ball in the white shirts of the Wrigley Field fans sitting in the centerfield bleachers, “but that’s what happens if you can’t see the ball. I stepped right into it. They took me out on a stretcher, and I was out for 18 days.”

Telling the assembled media after the exhibition against the Indians that they had just witnessed “the biggest thing that has happened to the game since night baseball,” MacPhail explained that Reese and Medwick had just adorned what he called “a protector for batsmen” without anyone noticing. The new device, while resembling a regulation baseball cap, in fact had plastic protectors inside.

“Every player in the Brooklyn organization will wear this protector,” said MacPhail. “And I want to make a prediction that within a year every player in the major leagues will be wearing it.

“But the objection I heard from other club owners was that the players never would wear them,” he added. “Well, they wouldn’t wear a thing that was cumbersome and so conspicuous that everybody could see it. My players are solid for this one, and they’re all going to use it.”

Hall of Fame second baseman Billy Herman admitted years later that he wouldn’t wear one of the newfangled caps until MacPhail made the team wear them.

“I didn’t want to do it. But I wore one after he made us. It was a stupid attitude. You didn’t want to give the pitcher the satisfaction of knowing you were covering up your head,” Herman said. “And it was rougher in those days. Umpires never tried to stop it. No warnings. No nothing. It lasted all afternoon.”

The design, based on head protectors worn by jockeys, is attributed to Dr. Walter Dandy and Dr. George Bennett, both of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. With the goal of making it as light and unobtrusive as possible, the plastic sections cover essential parts of the head on both sides of the cap, held in sleeves either sewn or zippered in.

“Every Dodger is wearing one and there isn’t a complaint,” MacPhail said. “I see where Bill McKechnie [Reds manager] says that he wouldn’t be able to make the Reds wear such protection but either he’ll change his mind or his players aren’t too smart,” MacPhail said. “Maybe there will be some slight improvement in the device after we use it for a while longer and find out more. But I am convinced that we are on the right track at last. This cap is the product of months of experimenting. The plastic has the strength to withstand the weight of a baseball travelling 100 miles an hour. It won’t completely eliminate the possibility of a player receiving a slight concussion at the plate, but it should entirely eliminate fractures.”

MacPhail would add that a patent had already has been applied for, “although neither of these two gentlemen was or is interested in making any money out of it.”

“The credit belongs almost entirely to MacPhail,” Dr. Bennett said. “MacPhail liked the idea, but, most important, he pushed it. He worked with many persons on it, then made its use compulsory for every player in the Dodger system.”

According to reports, the insert protectors were a DuPont product made of cellulose acetate plastic, its trade name Plastacel, which was “a very lightweight substance capable is distributing the shock from a hard and swiftly thrown baseball so that it amounts to little more than the shock of a run-of-the-mill hailstone.”

Medwick, the slugging outfielder who captured the National League MVP Award in 1937 with the Gashouse Gang St. Louis Cardinals, said after the Spring Training game said about the protective cap: “You’d never notice you had it on. There’s not enough difference in the weight or the feeling to bother anybody.”

Among the thousands of three-dimensional artifacts in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s permanent collection is one of these rare examples of headgear from the sport’s long history. Donated by the widow of Dr. Dandy in 1976, the blue Brooklyn Dodgers cap with a white “B” on the front has its plastic inserts sewn in. A manufacturer’s label inside reads, “Brooklyn Safety Cap – Patent Applied For,” with the name “Dandy” and “7 3/8” printed on the inside leather band.

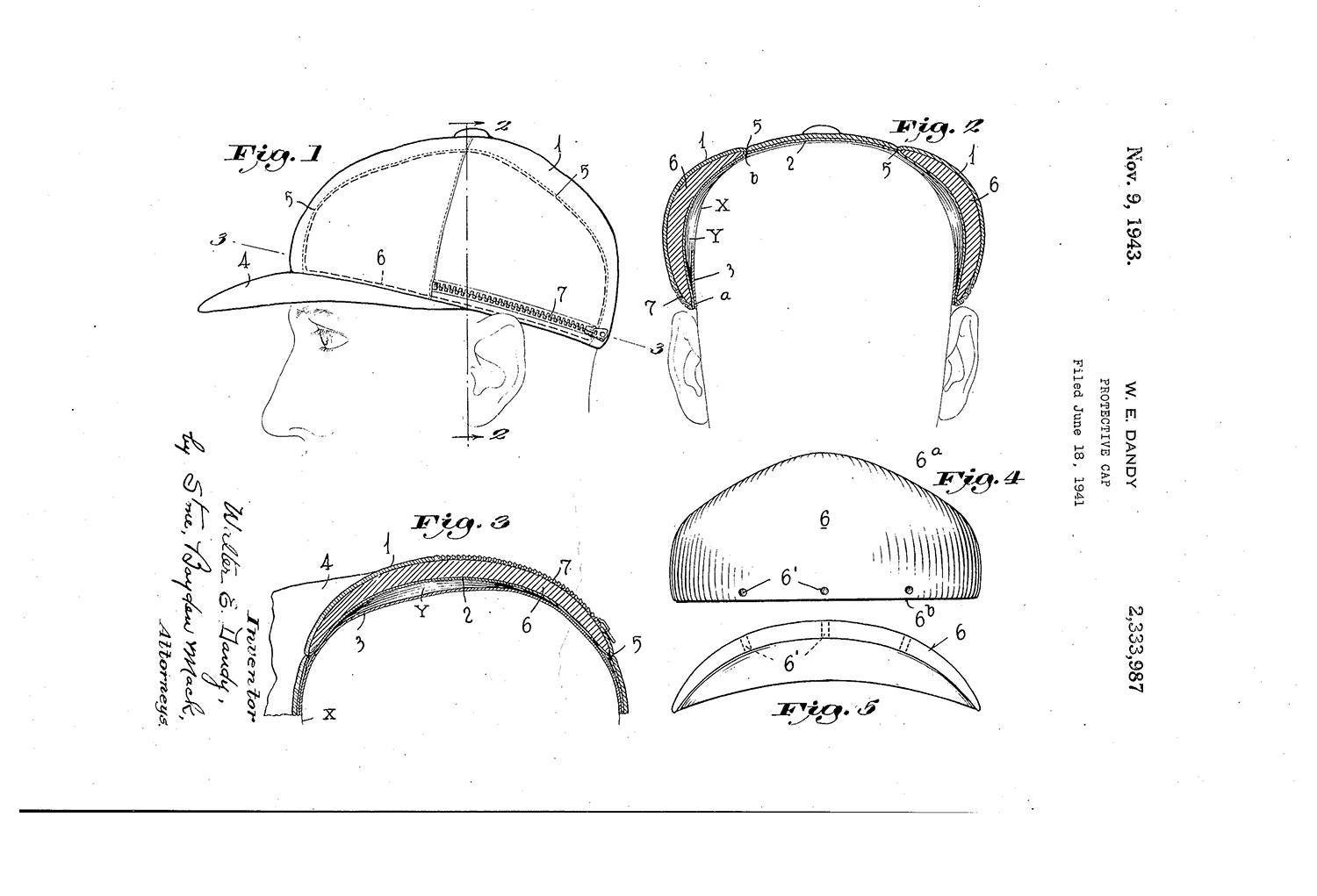

Dr. Dandy did apply for a patent for his protective cap in June 1941, the patent issued in November 1943. As part of his patent application, Dr. Dandy noted, in part, “As is well known, baseball players, especially when batting, are frequently struck on the head by a pitched ball and are sometimes badly injured. When at the bat, the side of the players head is disposed in the direction from which the pitched balls come, and thus the most vulnerable region, namely, the portion of the head just above and forward of the ear, is exposed to the danger of being hit.

“The general object of the present invention is to provide a cap having therein a protective shield or guard so positioned as to cover at least the most vulnerable portion of the players head.”

In February 1941, 21 years after the fatal beaning of Cleveland’s Ray Chapman, the Sporting News stated its case for sensible reform by the players: “Some day they will come to the conclusion it doesn’t pay to have their brains addled, skulls crushed and their careers shortened by wild pitches – and, in some cases, by ‘bean’ balls – perhaps their lives lost when they can avoid such catastrophic consequences by putting added protection inside their caps. If only one such accident is prevented, the helmet will prove its worth. It is to be hoped that players will ‘use their heads’ to give the new protective device a thorough trial, and if it is found it proves practical that the stars and rookies will universally adopt them.”

But players during this era often scorned protective headgear as unmanly.

“The ballplayer, quite naturally, is a sensitive figure,” said National League President Ford Frick in a 1940 interview. “He seems to feel that wearing protection up there is strictly sissy stuff.

“That’s too bad. What the player should do is consider the public more; his own vanity less.”

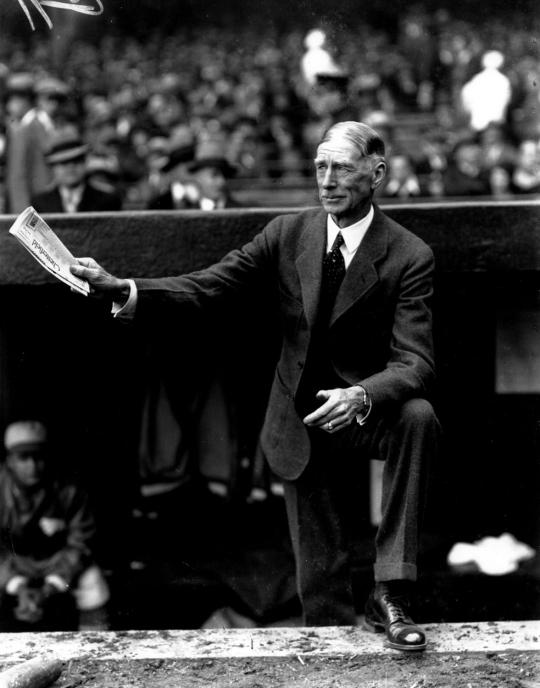

Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack, the legendary skipper of the Philadelphia Athletics, would offer his opinion in March 1941, a time when serious beanings in the game brought renewed attention to the issue.

“The man who invents a helmet that insures absolute protection will make a fortune,” the 78-year-old Mack said. “Some players may feel now it would reflect on their gameness to wear one but the time is coming when they will be standard equipment.”

Luckily for the Dodgers, when outfielder Pete Reiser was struck on the right side of his head by a pitch from the Phillies’ Ike Pearson in April 1941, subsequent x-rays showed no skull fractures. The attending doctor said the plastic protective plate which all Dodgers wear in their caps had saved Reiser from more serious injury, the ball connecting partly on the protector and partly on the right cheekbone, and the player would miss only two weeks.

With the evidence of the Reiser incident, the Senators and Giants announced that they too would be wearing a version of the new protective cap in 1941. But like previous attempts, these new helmets soon fell out of favor among players.

But common sense soon prevailed after decades of experiments, innovation and modification and nowadays it’s hard to imagine a big league hitter facing a pitcher with just a cap on his head. By 1958, both the American and National Leagues made it mandatory for its batters to wear some form of protective headgear; starting in 1971, all players were required to wear batting helmets.

“I may not look so hot in this thing,” said Hall of Fame third baseman George Kell, referring to a batting helmet, “but I’d rather be alive than pretty.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

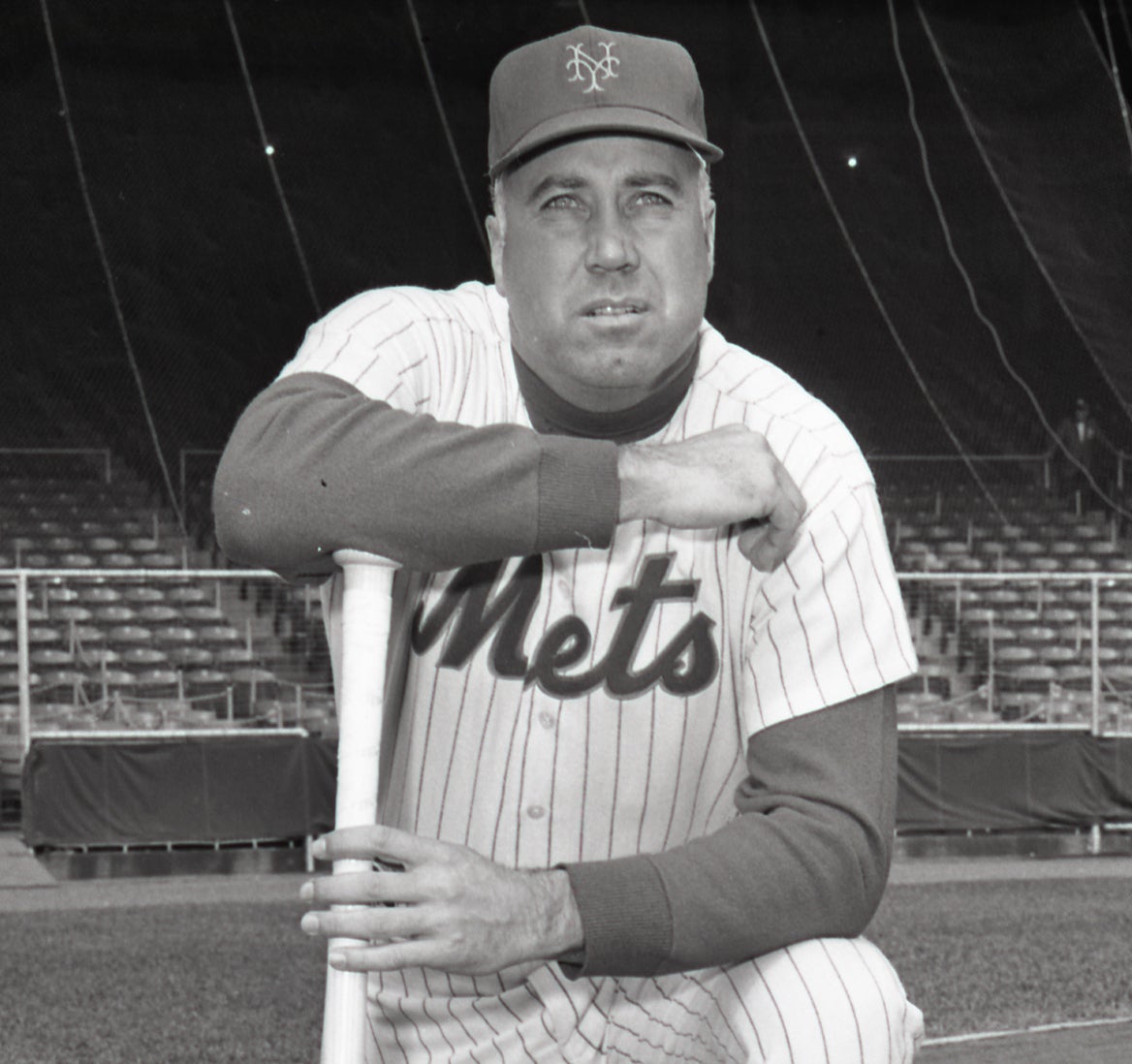

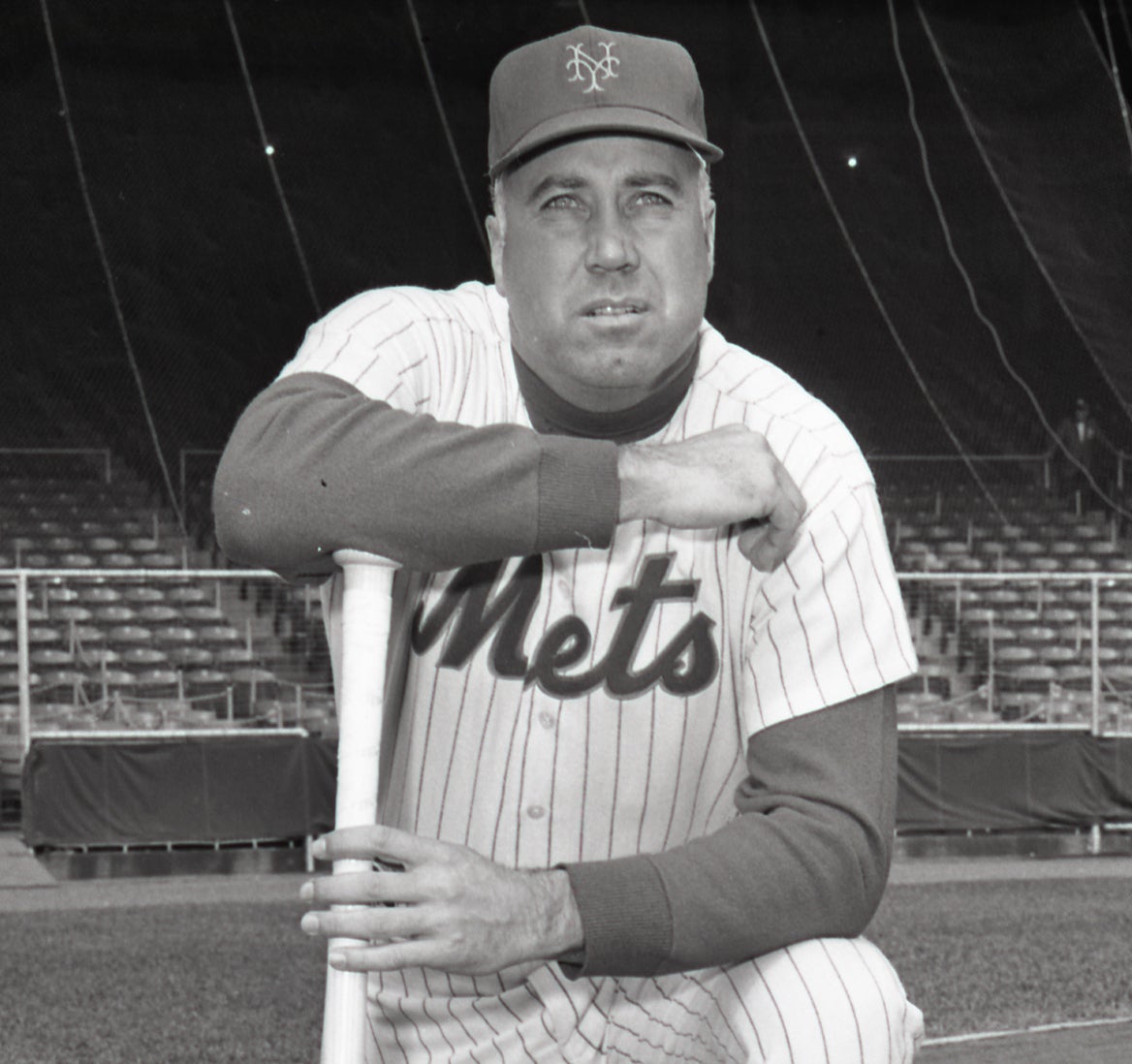

Dodgers sell Snider to Mets

Dominant Dodgers

Hall of Fame’s Picturing America’s Pastime Exhibit Opens Friday at Dodger Stadium

Vin Scully’s 2016 Dodgers Media Guide puts a 67-year long career into perspective

Dodgers sell Snider to Mets

Dominant Dodgers

Hall of Fame’s Picturing America’s Pastime Exhibit Opens Friday at Dodger Stadium