- Home

- Our Stories

- #Shortstops: Eliza Green became the first female official scorer in 1882

#Shortstops: Eliza Green became the first female official scorer in 1882

In celebration of Women’s History Month, the Hall of Fame presents a series of stories about legendary and pioneering women in baseball.

As a girl growing up near Rochester, N.Y., in the 1850s, Eliza Green was a frequent visitor to the nearby home of famed suffragist Susan B. Anthony. Some of Anthony’s can-do feminism must have rubbed off on the young woman. In her 30s, she would secretly become baseball’s first female official scorer, for the Chicago team now known as the Cubs. She served in this capacity from 1882-1891.

“I was living opposite the Chicago ball field at the time,” she recalled in a 1920 newspaper profile. “I was very much interested in the national sport and always kept a detailed score of the games.”

Mrs. Williams, as she was known at the time, was such a fixture at the ballpark, that she was familiar to Albert Spalding, the President of the Chicago Club. He was aware that she had a keen eye for the game and that she kept a mean scorecard.

Spalding was also dealing with a lot of “kickers” on his team. In the baseball lingo of the day, “kicking” referred to quibbling over decisions by official scorers, umpires, even the manager.

Players were very interested in getting awarded hits rather than errors, or in not being charged with errors in the field, so they would pester the official scorer.

Spalding decided to ask Mrs. Williams to become the club’s official scorer, and to do it in secret.

She would file the reports under her maiden name, and using only her initials, and thus the Cubs’ official scorer became “E.G. Green.”

“No one suspected me, not even Pop Anson’s wife, who sat beside me at many games and with whom I chatted freely concerning plays,” recalled Eliza in 1920.

Another source reports that she frequently sat in the player’s wives section. Her son later recalled: “Manager Anson never knew who was (the) official scorer for the club, nor did any of the players, newspapers, or the public. I used to mail the scores to league headquarters for her, and I did not know it. Even Nick Young, who received them, did not know who E.G. Green was.”

In an ironic twist, the players who were kicking over some of her calls came to ask her about them – not knowing that she was the official scorer.

“The funniest feature of my experience as official scorer was that some of the players, ascertaining that I was an expert, came to me to ask about certain plays over which disputes had arisen,” Green said. “They asked what I thought of the plays; were they correctly umpired, and was this a hit, was this an error? I told them what the plays, hits, and errors were, as I judged them to be, and they accepted my decisions without a protest. Not one of them suspected what I was really doing for club management.”

At some point her husband died, and she married John A. Brown, who was the team’s treasurer. Brown became stepfather to her son, Charles Green Williams, who later succeeded his father as treasurer of the team and also became traveling secretary – a position he held until jumping to the Federal League’s Chicago Whales in 1914.

E.G. Green stopped being official scorer in 1891, after 10 years with the club, due to an illness. Her second husband also died, and she married a third time, to Homer Daggett, of Attleboro, Mass.

The early lessons she learned from Susan B. Anthony stuck with her, and she became a seven-time National Secretary of the Women’s Relief Corps, from 1908-1924, serving as that body’s President in 1918-1919. She ran against four men for Mayor of Attleboro in 1920, though she didn’t win. She was thought to be the first woman in New England to run for such a position.

Tim Wiles is the former director of research for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#Shortstops: Another view of Effa

#Shortstops: Jimmy Dugan had it all wrong

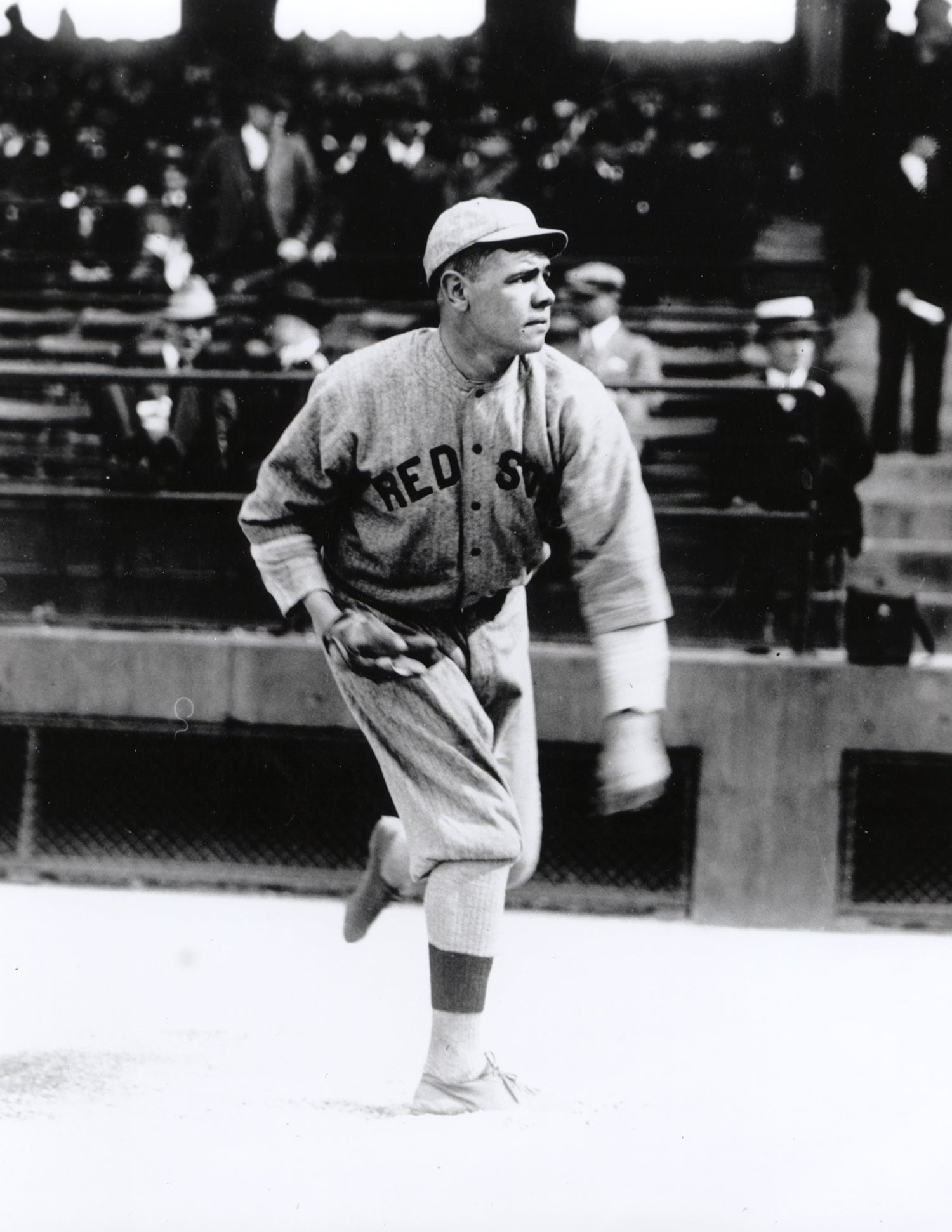

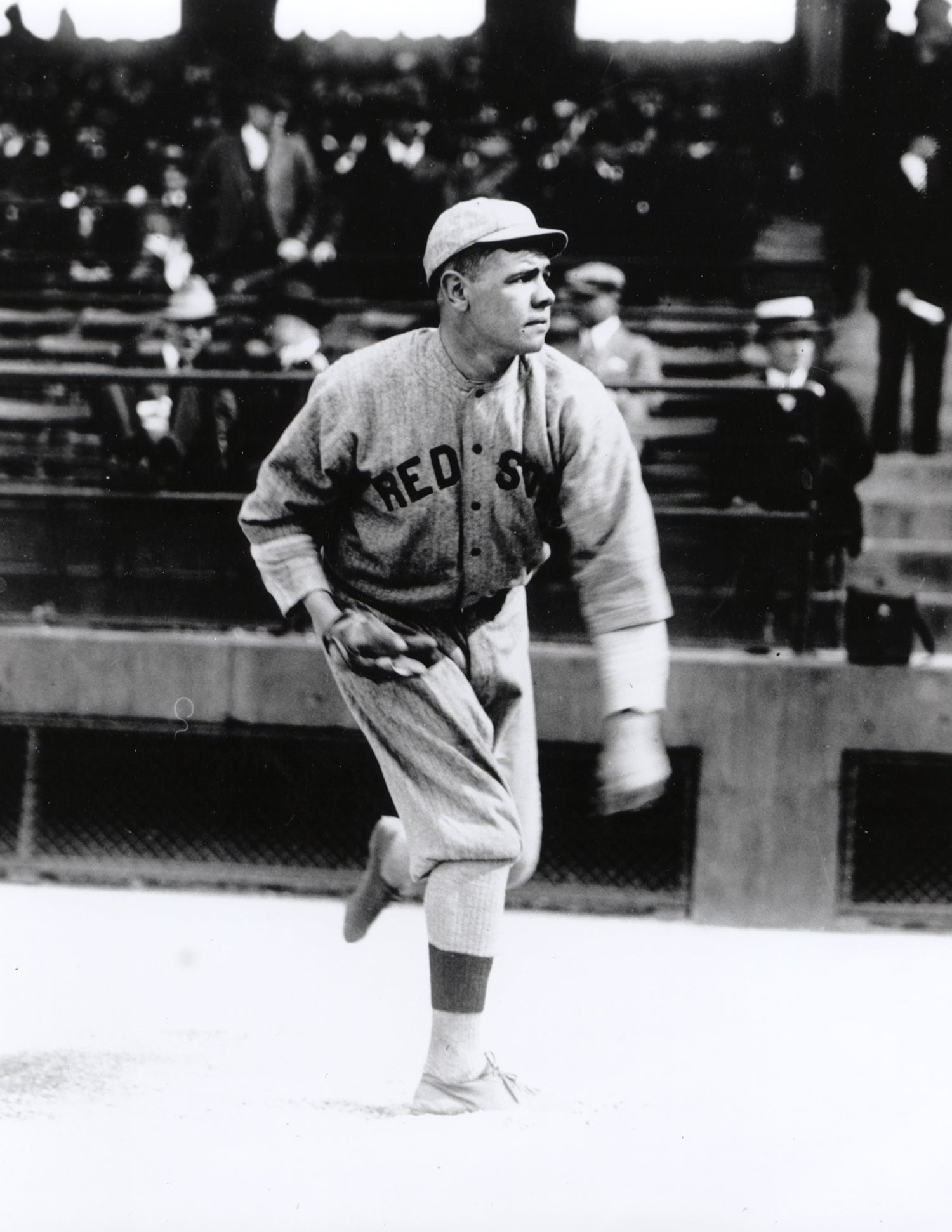

#ShortStops: The Sultan of Southpaw Shutouts

Related Stories

#Shortstops: Another view of Effa

#Shortstops: Jimmy Dugan had it all wrong