- Home

- Our Stories

- ‘Ruptured Duck’ patch honored soldiers, including ballplayers, who served in World War II

‘Ruptured Duck’ patch honored soldiers, including ballplayers, who served in World War II

At first glance today, the term “ruptured duck” sounds like a hunting trip gone awry. Yet, for those who wore the “ruptured duck” emblem, they saw it as a source of pride.

And like so many pieces of American history, the “ruptured duck” made its way onto the baseball diamond.

The emblem was part of what are officially called the “Honorable Service Lapel Button” and the “Honorable Discharge Emblem,” but it was often referred to as the “ruptured duck” because it was thought the eagle looked more like a duck in poor shape. Some cite actress Hedy Lamarr as being the source of the term.

Though it is not clear whether there is any connection to the emblem, one of the U.S. bombers used in the 1942 Doolittle Raid on Japan was nicknamed the “Ruptured Duck.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

According to the United States federal government’s Institute of Heraldry, the Honorable Service Lapel Button was worn by those who served honorably in the Armed Forces prior to Sept. 8, 1939, and were only to be worn on civilian clothing. In 1947, only those who served honorably between Sept. 8, 1939, and Dec. 31, 1946, were to receive the button.

The Honorable Discharge Emblem was to be worn on military uniforms by those who were honorably discharged or separated from the military. The Institute of Heraldry notes that the “emblem will be worn as a badge of honor indicative of honest and faithful service while a member of the Armed Forces during World War II.”

The emblem also served as an identifying marker, allowing military officials to know the serviceperson was now a civilian and had been honorably discharged even though he was still wearing a military uniform. Transportation companies also recognized the emblem as a sign to provide the veteran with free or discounted travel.

In 1945, as baseball’s military veterans returned to ballparks throughout the country, the United States government wanted to extend the emblem to those who had served their country.

At the National League’s midsummer meetings held on July 12, 1945, in Washington, D.C., Chicago Cubs owner Philip K. Wrigley presented the other teams’ representatives with the emblems as supplied by the War Department. Even Wrigley was not impressed with the emblem, calling it “poorly designed and really a terrible thing, but nevertheless, that is what they have got.”

Wrigley – with the War Department’s desire to “publicize recognition of the discharge emblem” – suggested increasing the size of the emblem and placing it on the shoulders of the uniforms worn by returning veterans.

The government’s goal was to have this in place by July 4, 1945, though there were regulations which delayed implementation.

Apparently, Branch Rickey was concerned with the public’s perception of those who did not serve as they would be distinguishable from colleagues who were sporting the patch. Wrigley felt the public would already know who served and who did not.

New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham and St. Louis Cardinals owner Sam Breadon were on Rickey’s side of the argument.

“We have several players who enlisted and were turned down, legitimate 4-F’s,” Stoneham argued. “They were not trying to evade service or anything like that, and if you put an emblem on one player’s uniform, it would be a startling contrast, wouldn’t it, to the fellow who did everything to get in?”

“I don’t think it would be a good thing, personally,” Breadon noted. “Because there will be a lot of ex-service men and they will be rooting for the ex-service men when they start to come back, and if you take one of them out when he ought to be taken out and some other fellow goes in, it might make trouble that way.”

Wrigley simply wished to let his National League colleagues know that about 300 patches would be available and assured them that wearing a patch would not be compulsory.

Some ballplayers, in the major and minor leagues, did choose to sport the emblem on their sleeve when they left howitzer blasts behind in favor of home run blasts or returned to throw heat instead of live grenades.

Hiram Bithorn, who went 18-12 for the Cubs in 1943 before joining the U.S. Navy and serving at the San Juan Naval Air Station in his native Puerto Rico, was discharged in early Sept. 1945 and returned to active duty at Wrigley Field. Though he rejoined the Cubs, Bithorn did not pitch during the remainder of the 1945 season. Yet he sported the patch on his jersey top. His teammates – Peanuts Lowrey, Paul Gillespie, and Mickey Livingston – did the same.

A photograph in the Aug. 2, 1945, issue of the Sporting News shows six members of the Pacific Coast League’s Los Angeles Angels proudly displaying their sleeve patches. The caption claims that the Angels were the first team – presumably the first minor league team – to adopt the emblem on the uniform.

A 1945 team photographs of the American Association’s Milwaukee Brewers also reveals various individuals wearing the patch.

Shortly after the National League approved use of the emblem, American League president William Harridge notified his circuit’s teams that the Cubs were using the patches. If they chose, American League clubs could do the same.

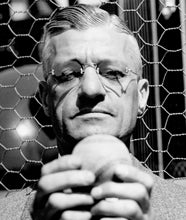

Alva Bradley of the Cleveland Indians returned the emblem sample Harridge sent, noting in his letter that “I would rather not have the Cleveland Ball Club get into this angle. I think it just as well that this be forgotten until the war is over.”

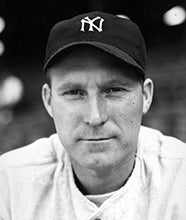

The New York Yankees felt otherwise. Pitcher Red Ruffing, who spent his time in the service in non-combat duty, came back to Yankee Stadium in 1945 and sported the emblem on his sleeve. Catcher Aaron Robinson joined Ruffing in wearing the patch.

Many Major League Baseball teams wore special uniform patches throughout World War II, but the “ruptured duck” patch was a source of pride for those returning ballplayers who served in the conflict. Though there does not seem to be any note of enmity between those who served and wore the patches and those who did not serve or served and chose not to wear the patch, those who sported the “ruptured duck” on the baseball diamond set themselves apart in more ways than one.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#GoingDeep: Reflections on World War II

Team Tours of Japan bridged cultural gap following World War II

Hall of Fame Veterans

#GoingDeep: Reflections on World War II

Team Tours of Japan bridged cultural gap following World War II