- Home

- Our Stories

- Proof on paper

Proof on paper

For accountants, a day’s work is not complete until the books are balanced.

For official scorers, the same holds true – except the books in question are scoresheet pages.

Stew Thornley has been balancing the books after Twins home games since 2007, serving as one of Major League Baseball’s official scorers in Minnesota. For him, the period of time following a game is a chance to go over his scorecard and transfer that information to the official scoresheets.

“We still do a paper scoresheet and it goes to Elias (Sports Bureau). To me, it’s a good thing to do,” said Thornley, a Minnesota native. “It’s nice when it gets quiet, and I enjoy doing it after the game, just as I enjoy filling [my score card] in as the game goes on.”

Broadcaster Doug Greenwald keeps score during a Spring Training game between the Giants and the White Sox in Scottsdale, Ariz. Hand-written scorecards and scoresheets are the first draft of history for baseball – and hundreds are preserved in the Library Archive at the Hall of Fame. (Brad Mangin/National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

It is important to note the difference between a scorecard and a scoresheet. Scorecards are what the official scorer and many fans around the ballpark use to keep track of the game’s action. The scoresheets, typically paper, function as extended box scores, providing a breakdown of each player’s statistics in hitting, fielding, and pitching, as well as any additional notes of events which happen during the game. These events may include instant replay challenges, ejections, or rain delays.

Each official scoresheet must be proven before it is sent to the Elias Sports Bureau, Major League Baseball’s official statistician. In other words, for each team, the total of runs, men left on base and opponent’s putouts must equal the number of at-bats, walks, sacrifices, hit batsmen and number of times first base is awarded due to interference. If these sums are equal for both teams, then the box score is considered proven.

Once the official scorer finalizes the game’s scoresheet and sends it off to Elias, typically the paper copy remains.

“We fax them or scan them or email them, so they still will go in to Elias, but there is the digital record that is done by MLB.com that goes in,” Thornley explained. “I would imagine to be able to spit out all of the information that goes into the stat packets the next day, there is probably a … computer taking those terabytes of information and processing them like that.

“The computer can also do more things than you would even have with the official scoresheets: Coming out with batting average, statistics against left-handed hitters or pitchers, or (statistics) with runners on base. The MLB.com version submits that file. But we as official scorers still fill out that scoresheet. … It takes about 20 minutes. It’s kind of relaxing. I find it to be a nice way to unwind after the game.”

And sometimes that leftover handwritten copy finds its way to Cooperstown.

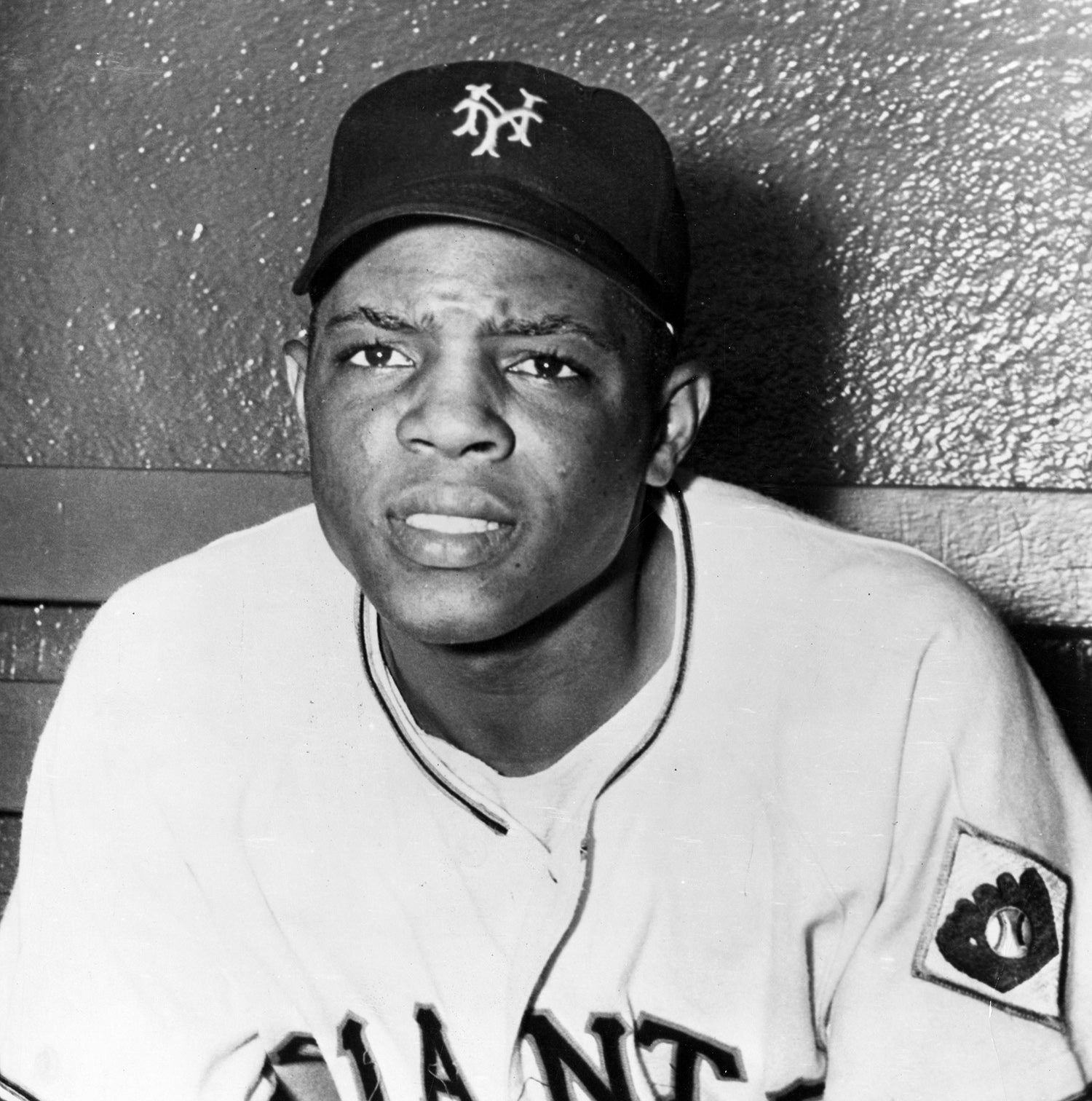

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Library has hundreds of scoresheets in its collection, many of which cover notable events in baseball history, and it received a considerable boost with the recent donation of scoresheets from New York Yankees home games. The Yankees scoresheets, covering much of the 2010 Postseason through the 2015 regular season, include achievements from players who may one day grace the Induction Stage in Cooperstown. Included are the scoresheet for Mariano Rivera’s final game, against Tampa Bay on Sept. 26, 2013, as well as the game (May 7, 2015 against Baltimore) in which Alex Rodriguez hit his 661st career home run, surpassing Willie Mays on the all-time home run list.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

“We are excited to add these scoresheets to our collection,” said Jim Gates, Librarian of the Baseball Hall of Fame. “With so much recordkeeping going digital, these documents show that handwriting still has its place in baseball. Along with the scorecards, they are solid documentation of what goes on in every Major League Baseball game.”

The Hall of Fame Library’s collection already featured scoresheets from numerous postseason games, including Game 6 of the 1975 World Series, which featured Carlton Fisk’s famous round tripper; the Sept. 30, 1972, game in which Roberto Clemente recorded his 3,000th and final hit; the first games played in San Francisco and Los Angeles in 1958 between the Giants and the Dodgers; and Bob Feller’s Opening Day no-hitter in 1940.

Gates, who has also served as an official scorer for nearby minor league and collegiate summer league games, noted that he uses his iPad to keep track of the play-by-play and simply submits the game data to the league not long after the last out. Technology might be making deep inroads into official scoring, but there is still a place for an individually compiled scorecard.

While most scoresheets contain similar information, the scorecards which contain the original information are “like snowflakes,” Thornley claims. “You’ll never find two alike.”

“I sort of like it, at the end, to look at (the scorecard), and it’s a work of art in the sense that it’s like a musical score of a great piece of music,” he said. “In the hieroglyphics that you have and the stanzas and things in a musical score that represent the music. This represents baseball and what happened, but the person recording it with baseball isn’t the composer of it. The people on the field are.”

One piece of data on the scoresheet which does not make it to the box score is the name and affiliation of the official scorer. Thornley and other members of the Society for American Baseball Research have created a committee to chronicle these individuals, using the Hall of Fame’s scoresheet collection as a jumping off point.

“For me, a big part of it is, as much as we can, to chronicle the history, both in overall trends from the 1880s when it was disorganized, to the time of the BBWAA taking it over, to when that transition was made when it wasn’t beat writers doing this on top of their regular jobs because there wasn’t a conflict of interest,” said Thornley, who also was interested in finding examples of “specific stories, incidents, things that have affected milestones or league leadership.”

Though their work appears every day in newspapers and on the internet, the names of past official scorers remain largely hidden from view.

“I think the recognition is good,” Thornley said. “They’re an important part of [baseball history], and with this committee too, is to raise the role and stature of official scorers too.”

With continued contributions to the Baseball Hall of Fame Library through scoresheet donations and additional research from SABR, additional light will be shed on those persons whose worth – and work – is proven night after night.

Matt Rothenberg is the manager of the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum