- Home

- Our Stories

- PCL helped propel baseball to its destiny

PCL helped propel baseball to its destiny

Like the prospectors who rushed west in the middle of the 19th century in search of precious metal, professional baseball eventually would discover there was gold in “them, thar hills” on the Pacific Coast.

And that would lead to the formation of a league in 1903, which for nearly a half-century would rival and – in some cases – outshine the established big leagues that had set up shop east of the Mississippi.

The Pacific Coast League eventually would be regarded by many as “the third major league,” and prompt MLB to finally realize in 1958 that there was a geographic void to be filled, resulting in the relocation of the Dodgers from Brooklyn to Los Angeles and the Giants from Upper Manhattan to San Francisco.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Other PCL markets later would be absorbed, with additional big league franchises sprouting in L.A. and the Bay Area, as well as in Seattle, San Diego and Phoenix as part of a major expansion that would mirror the country’s westward migration.

If the ambitious PCL owners and administrators had their druthers, MLB would have put down stakes in the west much sooner, with the Pacific Coast joining the American and National leagues at the game’s highest level. As it turned out, the establishment’s refusal to satisfy those ambitions actually worked to the PCL’s advantage as the circuit enjoyed several decades of prosperity, in some instances drawing bigger crowds and outbidding big-league clubs for skilled players.

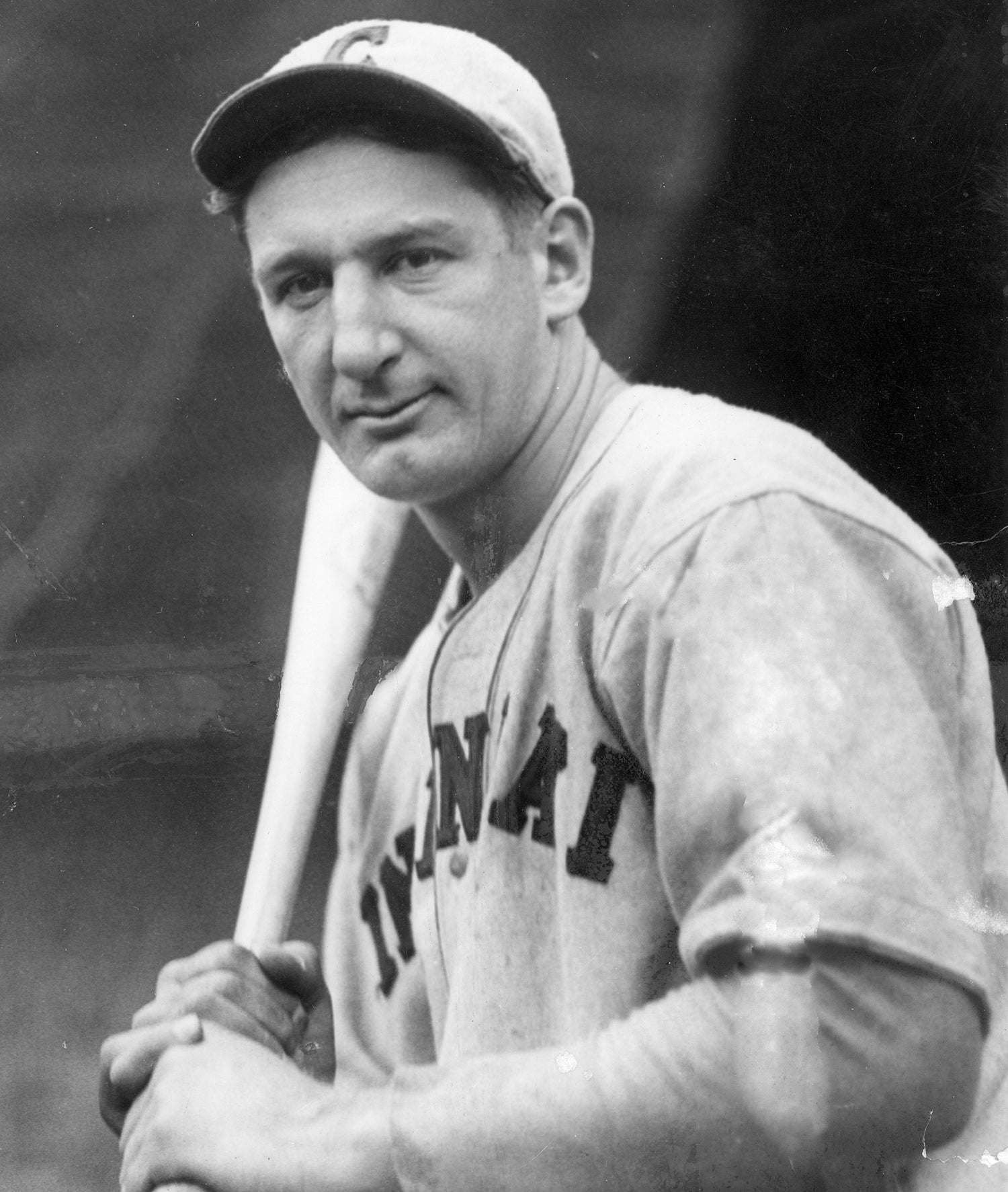

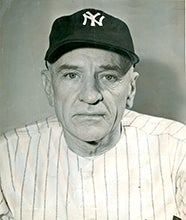

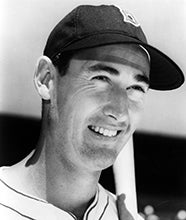

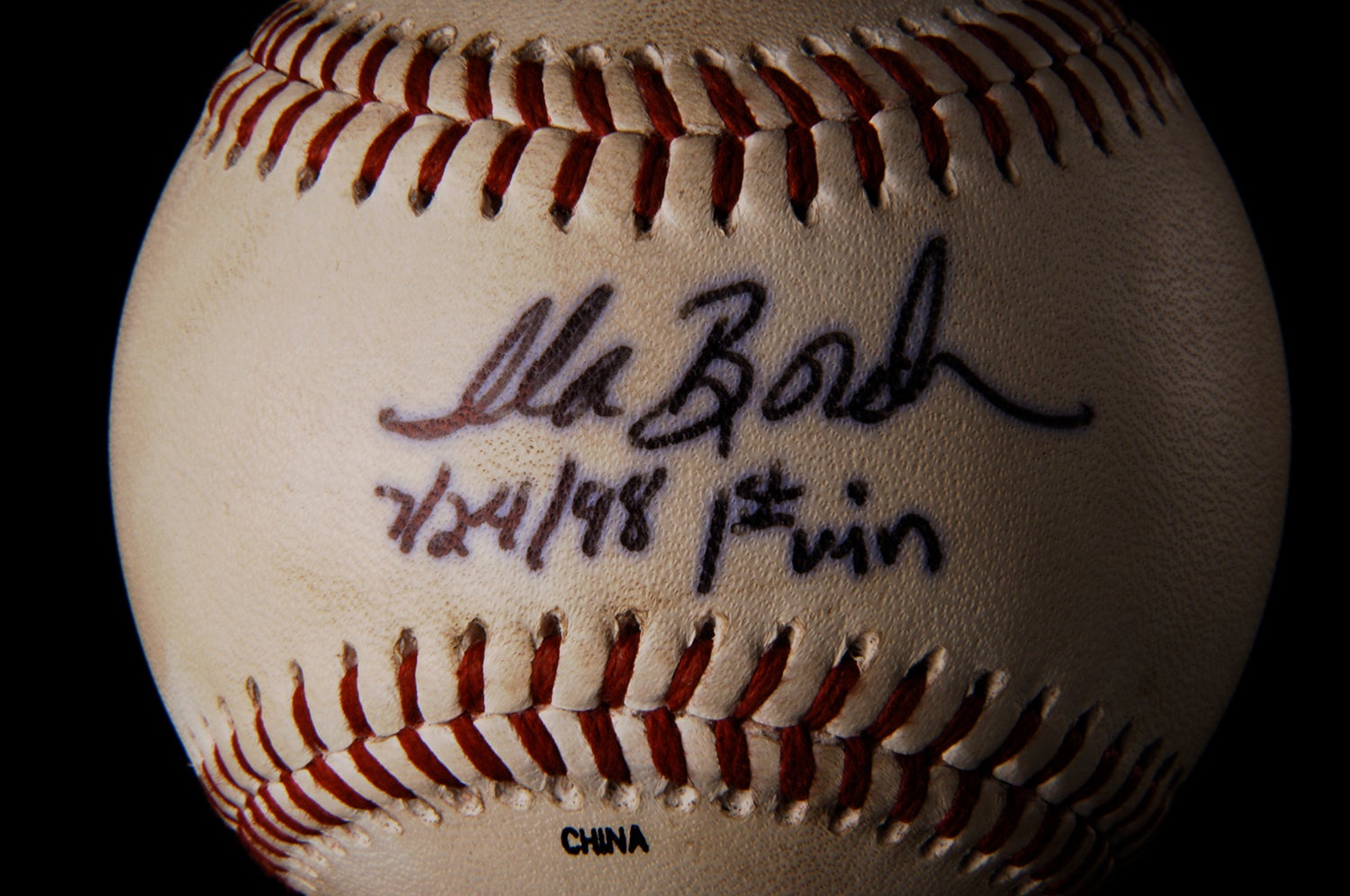

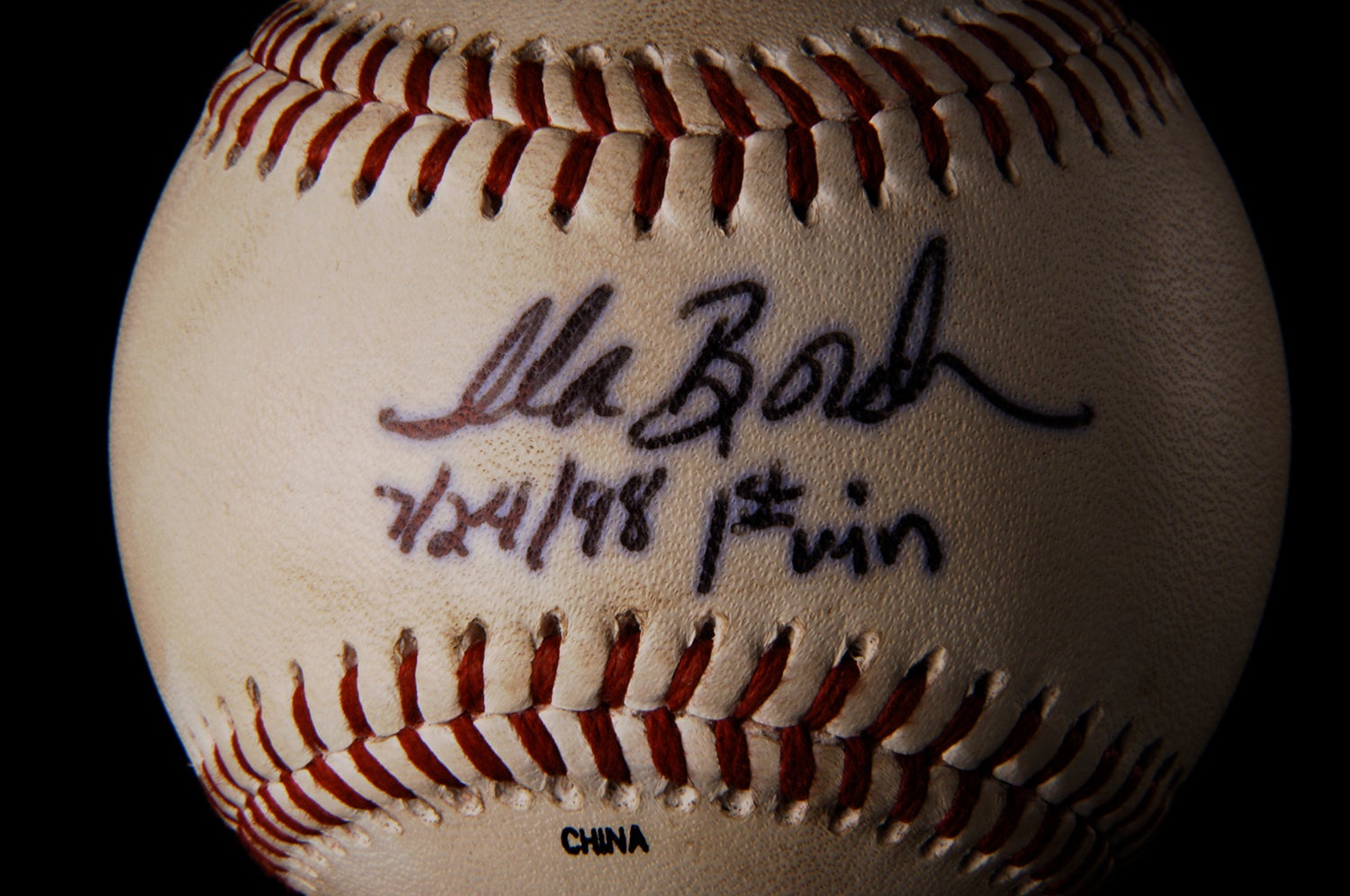

Roughly 60 members of the Baseball Hall of Fame have PCL ties. Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams began their Cooperstown journeys there. And Casey Stengel revived his left-for-dead managerial career there, catching the eye of the New York Yankees, who would take a chance on the “Old Perfesser” after he won a PCL title with the Oakland Oaks at the then-advanced age of 58 in 1948. Still other Hall of Famers – such as catcher Ernie Lombardi – would wrap up their professional careers in the PCL, earning robust salaries on the Left Coast after their big-league days were done.

The league also would produce a busload of players who would become West Coast baseball folk heroes. They would include legends such as Frank Shellenback, Jigger Statz, Steve Bilko and Ox Eckhardt.

“Many of these guys performed in era before the widespread availability of television, so they became as popular to West Coast fans as Major League Baseball stars were to fans on the East Coast and in the Midwest,’’ said Mark Macrae, director of the Pacific Coast League Historical Society. “And some fierce rivalries developed. The one between the Hollywood Stars and Los Angeles Angels became every bit as intense as the Dodgers-Giants and Yankees-Red Sox.”

There were times when the PCL proved to be ahead of the curve. One example being when it staged its first night game on June 10, 1930 in Sacramento – a full five years before an MLB team played under the lights.

“The biggest thing the old PCL had going for it was geography,’’ Macrae said. “When you look at the original 16 major league teams, they didn’t spread beyond St. Louis and the Mississippi River. So, you had this void of 1,600 to 1,800 miles where there wasn’t any quote-unquote major league baseball.”

The West Coast’s baseball roots run Grand Canyon deep.

“The sport had been played there since the Gold Rush of 1849,’’ Macrae said. “The Cincinnati Red Stockings barnstormed there and several teams began coming to California for spring training, so West Coasters had a long history of not only playing the game, but being fans of it. And as transportation improved, with the completion of projects such as the Transcontinental Railroad, there was a population boom and interest just kept mushrooming.’’

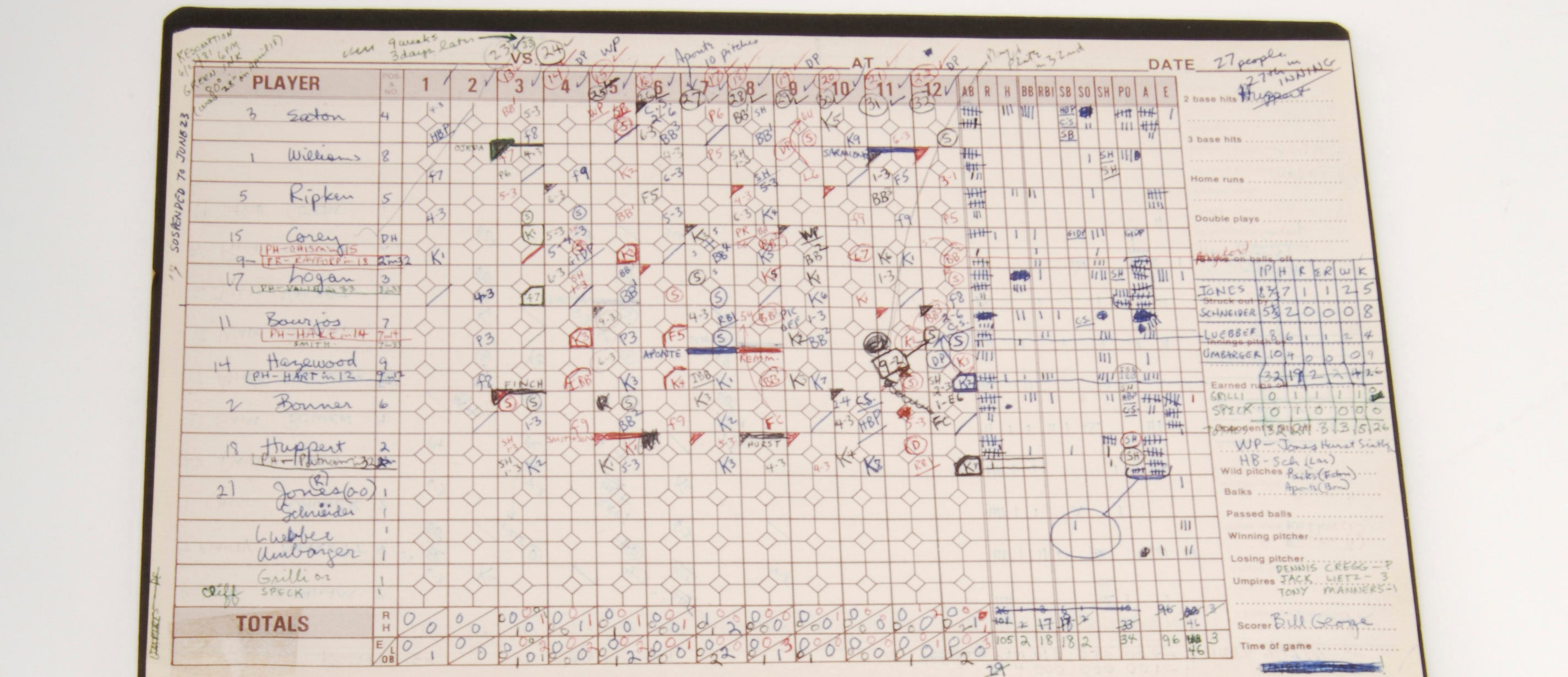

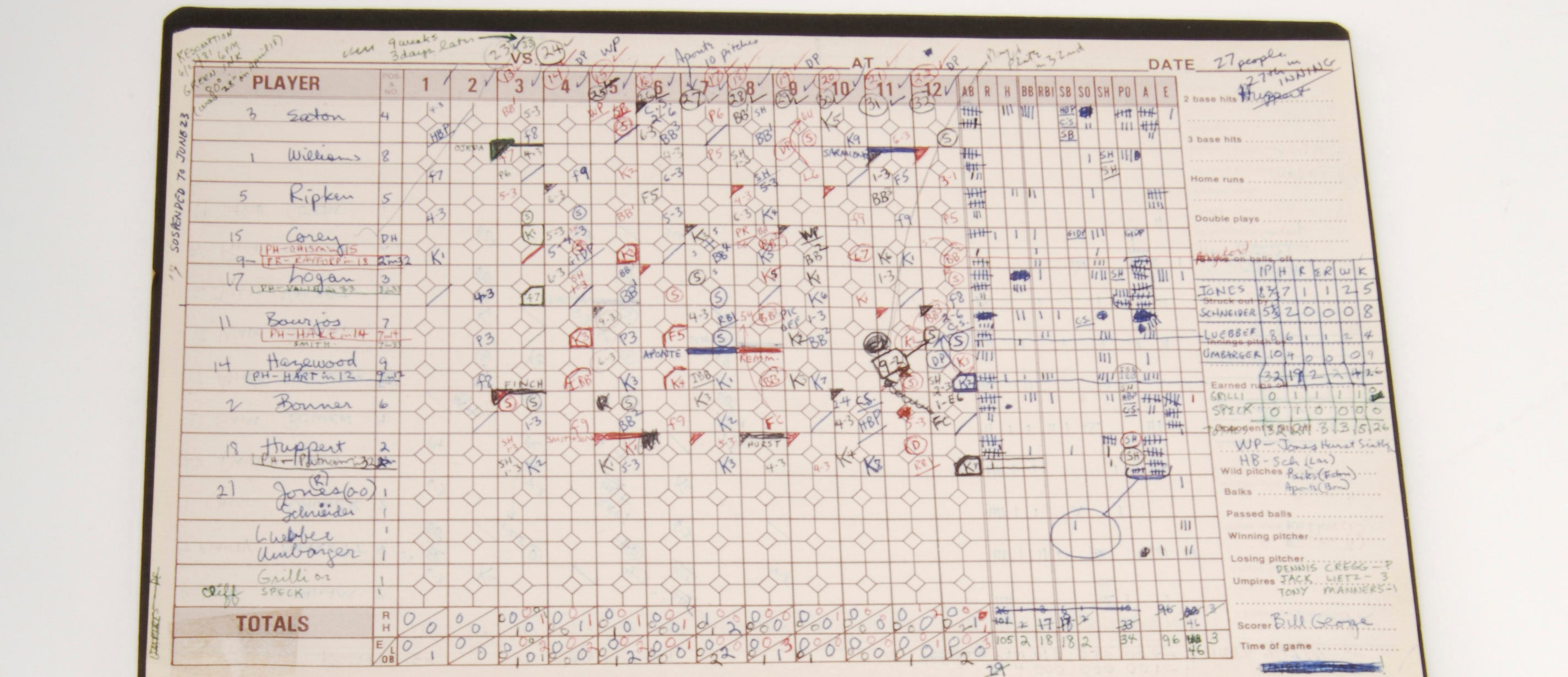

Climate also was a factor. Relatively calm winters enabled baseball to be played almost year-round, with PCL seasons running from late February to late November. Clubs averaged 180 games and schedules occasionally went longer, with the 1905 San Francisco Seals logging a PCL-record 230 games. The ideal weather and longer seasons were strong selling points during an era when ballplayers had to work off-season jobs to make ends meet.

“By extending your season by a month or two, that meant less time for players having to work often rigorous non-baseball jobs,’’ Macrae said. “You could extend your paychecks and make more money doing what you loved.”

And the salaries they received often were competitive with what American and National League clubs were paying. That, along with a less onerous travel schedule, prompted many players to eschew big league opportunities.

“PCL travel wasn’t as taxing as travel in the big leagues, where you might spend two or three days in a city, before climbing back onto the train,’’ Macrae said. “In the PCL, you’d spend six days in a visiting city. You didn’t feel as if you were constantly packing and unpacking a suitcase.”

The longer seasons contributed to some amazing records, including several that may never be broken. One such mark was established by the PCL’s Angels, who went 137-50 in 1934. That’s 21 more regular-season wins than the MLB record-setting 2001 Seattle Mariners. If you add on the six postseason wins the Angels recorded against the PCL All-Stars, the total balloons to 143, 18 more victories than the MLB combined regular/postseason record established by the 1998 Yankees.

It’s a safe bet, too, that spitballer Frank Shellenback’s career PCL pitching record of 295-178 will stand the test of all-time. He had pitched parts of two seasons with the Chicago White Sox, but when MLB outlawed his go-to pitch before the 1920 season, the man known as “Shelly” headed to Los Angeles and fashioned one of the most amazing pitching careers in professional baseball history. He amassed a 316-191 record, the vast majority of those minor-league decisions coming while pitching for PCL teams in Vernon (Calif.), Sacramento, Hollywood and San Diego.

Other minor league hurlers had won more games, but none of them did it against the caliber of hitters Shellenback faced.

Outfielder Arnold “Jigger” Statz is another legend whose PCL records appear unassailable. In 18 seasons with the Los Angeles Angels, he established marks for hits (3,356), runs scored (1,996), doubles (597), triples (136) and games played (2,790). Statz also spent eight seasons in the majors, and if you tack on the 737 hits he had playing for the Giants, Boston Red Sox, Chicago Cubs and Brooklyn from 1919 to 1928, he has a total of 4,093 hits, making him one of just seven players in professional baseball history to surpass the 4,000 mark.

This cap from the Pacific Coast League’s Hollywood Stars was worn by Charles Redling on July 5, 1930, in his only appearance in the PCL. The PCL featured some of the game’s best hitters and pitchers of the first half of the 20th century. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Statz also would receive minor acclaim for the technical advice he gave Ronald Reagan in the future President’s portrayal of pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander in the film “The Winning Team.” Hollywood connections would be another perk for PCL players, managers and owners, who would serve as consultants or doubles in baseball-related movies.

Perhaps no one took greater advantage of this proximity to the film and television industry than strapping Angels first baseman Chuck Connors, who wound up starring in several shows, most prominently as rancher Lucas McCain in “The Rifleman,” a popular late-1950s, early 1960s TV series.

L.A.’s Wrigley Field would become a regular filming site. “The Pride of the Yankees,” starring Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig, was shot there, as was the television show, “Home Run Derby,” featuring matchups between sluggers such as Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron and Harmon Killebrew.

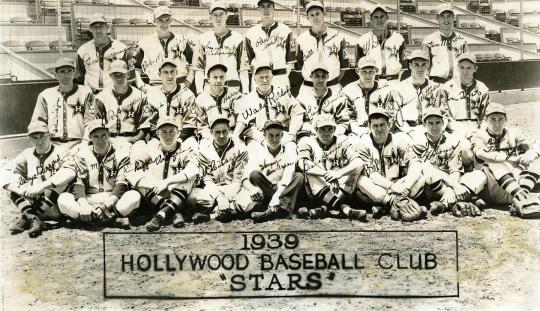

The 1939 Hollywood Stars featured almost two dozen players who appeared in a big league game, including future All-Star pitcher Bob Muncrief and former Brooklyn Dodgers star Babe Herman. The photo shows the uniform patch worn by teams throughout the 1939 season celebrating baseball’s centennial, which included the opening of the Hall of Fame. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Like Statz, Hall of Fame second baseman Tony Lazzeri holds a prominent place in the PCL record books. As a 21-year-old playing for the Salt Lake City Bees in 1925, he became the first player in professional baseball to slug 60 homers in a season. He also drove in 222 runs and scored an additional 202 while playing in 197 games that season. The Bees would sell his contract to the Yankees in 1925, and two years later Lazzeri would have a front-row seat as Babe Ruth became the first MLB player to smack 60 in a season. The Bambino almost had a PCL tie, too. Following the 1943 season, Ruth reportedly turned down the Oaks’ offer of $15,000 to manage their team, standing firm on his demand for $25,000.

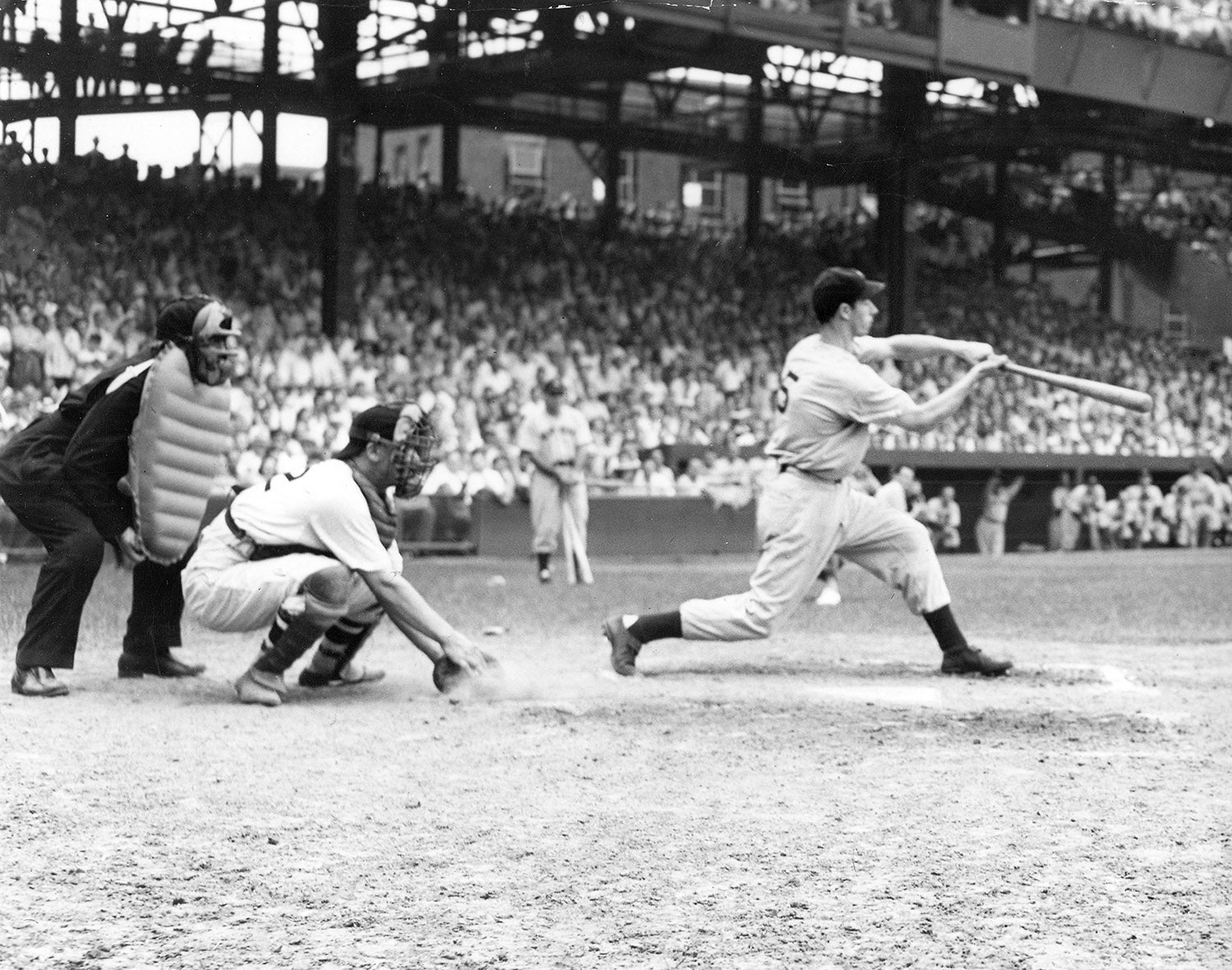

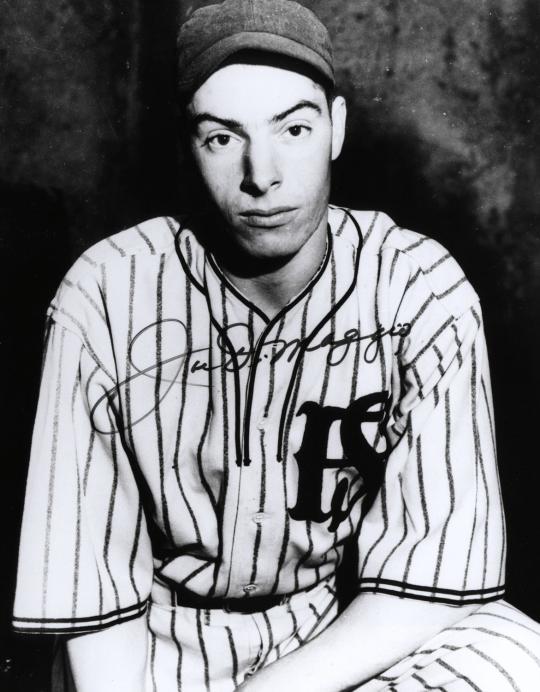

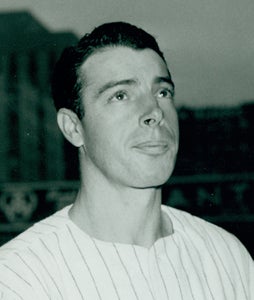

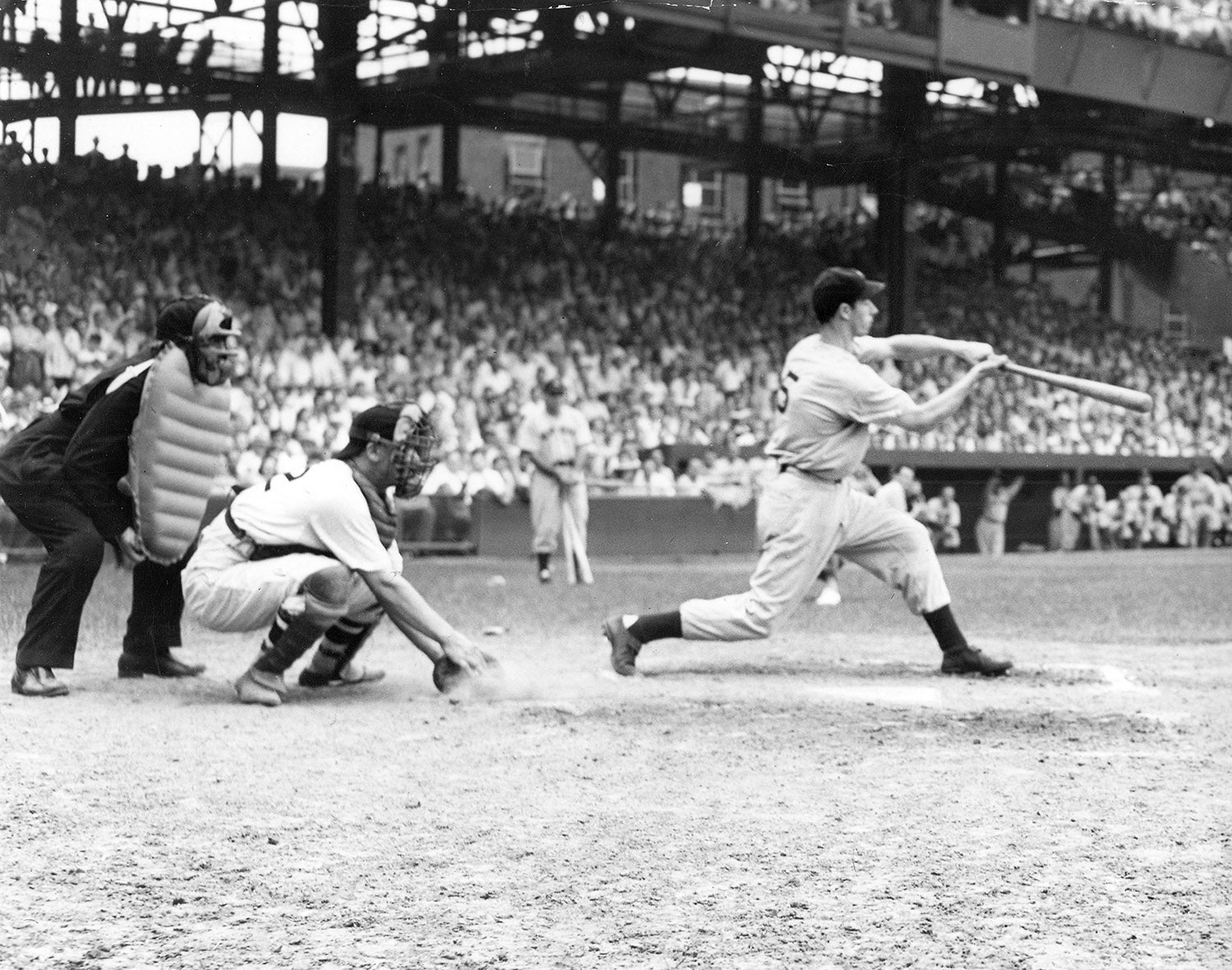

DiMaggio was another Yankee legend who left his mark on the PCL. In his three full seasons with the San Francisco Seals, he batted .340, .341 and .398, respectively, and past would become prologue during the 1933 season when he hit safely in 61 consecutive games. Known as “Deadpan Joe” because his face remained expressionless under pressure, DiMaggio would admit to feeling a great sense of relief when the streak finally ended. Two years later, he would sign with the Bronx Bombers, and in 1941 he would captivate the nation while hitting safely in 56 consecutive games.

Despite his impressive minor league streak, DiMaggio was not considered the best PCL hitter of that era. That distinction belonged to Ox Eckhardt, a raw-boned Texan, who still holds the league record with his .414 batting average in 1933. He batted .369, .371, .378 and .399 in four other seasons in the PCL, but his magic wand wasn’t magical in the big leagues, as he finished with a career .192 average in parts of two seasons. Still, his combined average of .366 is the best in professional baseball history, fractionally ahead of MLB record-holder Ty Cobb.

Slugger Steve Bilko also compiled scintillating PCL stats that didn’t translate into MLB stardom. From 1955-57, he crushed 148 homers and drove in 428 runs for the Angels while winning three consecutive league MVP awards, but he managed only 76 homers in 600 MLB games over 10 seasons.

Lefty O’Doul would win two National League batting titles and finish his 11 MLB seasons with a career .349 batting average, trailing only Cobb, Rogers Hornsby and Shoeless Joe Jackson on the all-time list. But the man who helped popularize baseball in Japan also proved his mettle as the PCL’s all-time winningest manager, posting a 2,094-1,970 record while piloting clubs in San Francisco, San Diego, Oakland, Vancouver and Seattle.

If owner and league president Pants Rowland had his way, the PCL would have leaped its “major” hurdle, but the American and National leagues were intent on maintaining a two-league setup. The best MLB would do was grant the PCL “open classification,” which gave the league the highest status ever accorded a minor league – a step above the Triple-A ranking of the International League and American Association, but a step below the bigs.

The relocation of the Dodgers and Giants put an end to any more talk about the PCL joining the big leagues. Several of its cities would be usurped by MLB, but the PCL would continue on at the highest level of the minor leagues – a distinction it still holds today.

Scott Pitoniak is a freelance writer from Pittsford, N.Y.

Related Stories

Nothing Minor About It

#Shortstops: No minor achievement

#Shortstops: Hooray for Hollywood

Joe DiMaggio makes his big league debut, recording three hits in the Yankees’ win

Nothing Minor About It

#Shortstops: No minor achievement

#Shortstops: Hooray for Hollywood