- Home

- Our Stories

- New book details making of ‘Pride of the Yankees’

New book details making of ‘Pride of the Yankees’

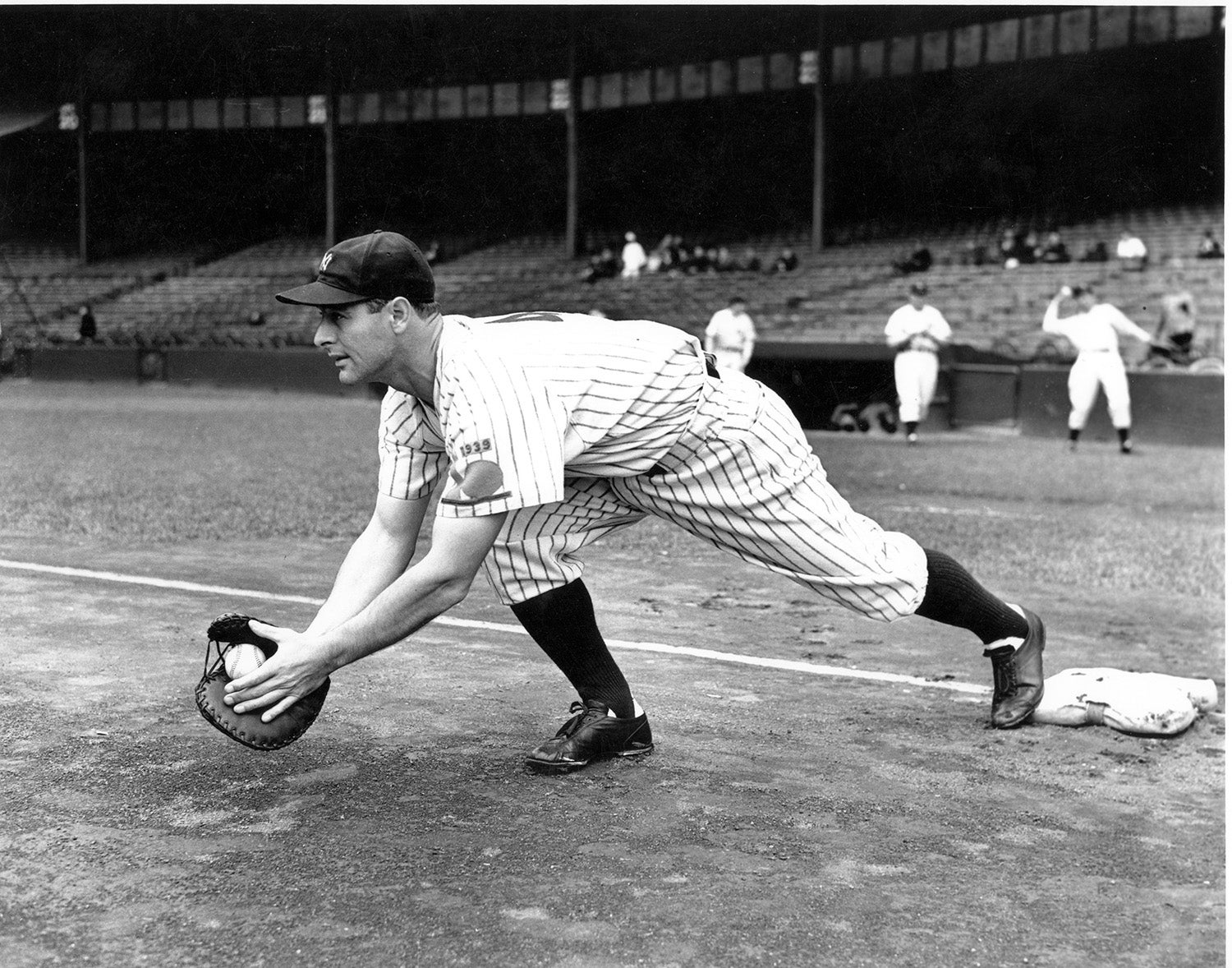

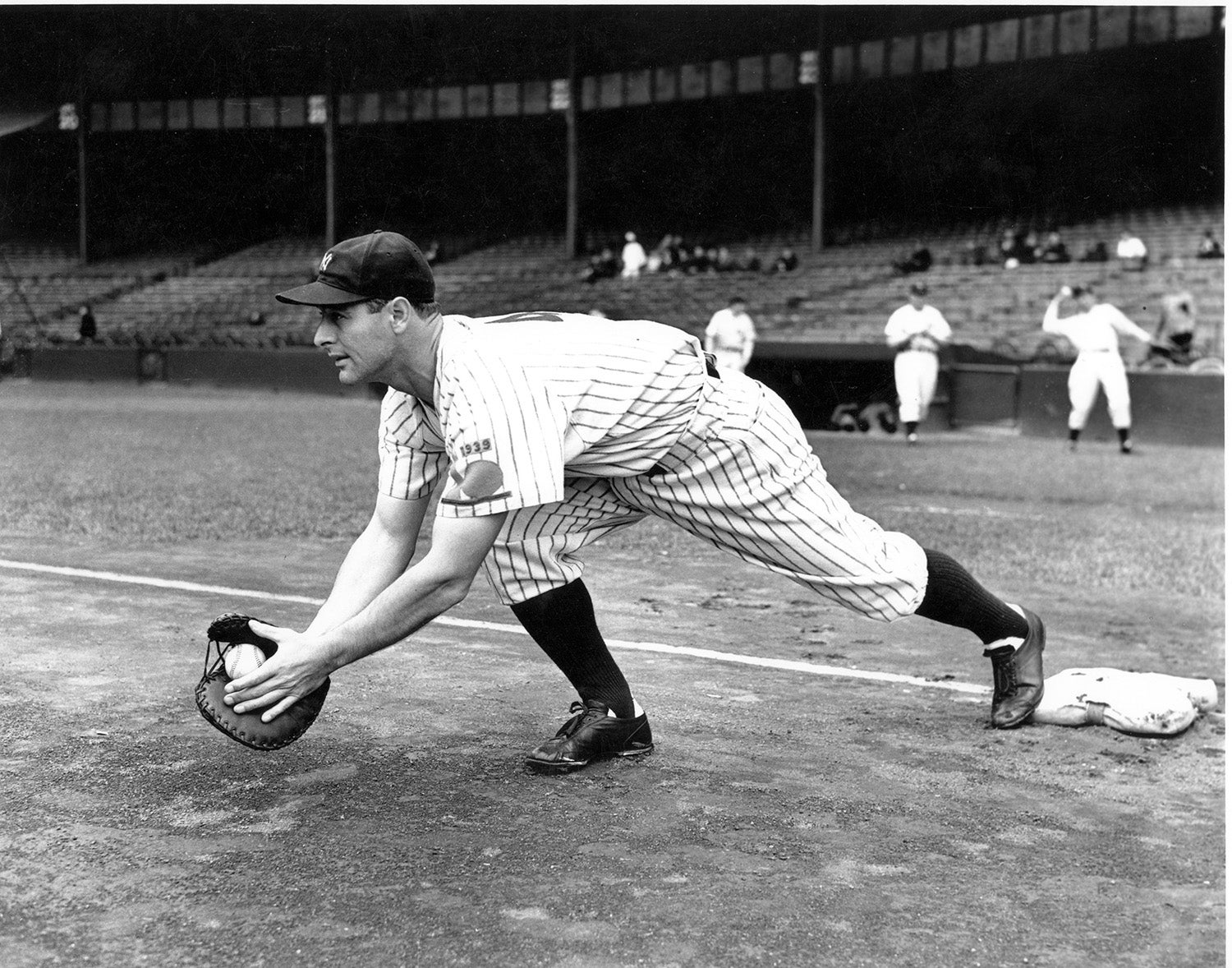

Seventy-eight years ago, on July 4, 1939, Lou Gehrig, beloved by the public for his 2,130 consecutive-games-played streak, made one of the most memorable speeches in the annals of sports. Heartfelt and poignant, this man with less than two years to live shared his deepest feelings with a stunned Yankee Stadium crowd.

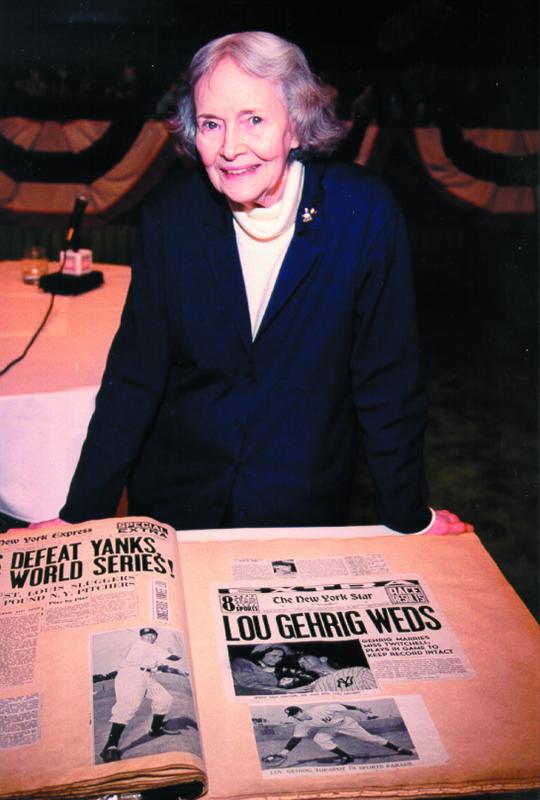

Gehrig’s life story would famously reach the silver screen in 1942 with The Pride of the Yankees, starring Gary Cooper as the strapping first baseman of the New York Yankees and Teresa Wright as his devoted wife Eleanor. The making of the famed biopic is the subject of author Richard Sandomir’s new book, The Pride of the Yankees: Lou Gehrig, Gary Cooper, and the Making of a Classic.

Sandomir, a reporter for The New York Times, will take part in the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s summer Authors Series program. He’s scheduled to talk about his book at the Museum’s Bullpen Theater at 1 p.m. on Wednesday, June 28, with a book-signing to follow.

It was on Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day, when the Iron Horse uttered the famous words at a home plate ceremony at Yankee Stadium: “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The next day’s New York Times wrote “the vast gathering, sitting in absolute silence for a longer period than perhaps any baseball crowd in history, heard Gehrig himself deliver as amazing a valedictory as ever came from a ball player.”

Gehrig had been forced to retire as a player two weeks earlier due to his being diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, the disease that today bears his name. But on this hot and muggy day, he was being showered with kind words and numerous gifts.

The Independence Day event, held between games of a doubleheader against the visiting Washington Senators, saw 61,808 fans pack the bunting-draped ballpark. For over 40 minutes Gehrig was heralded by members of the 1927 Yankees (including Murderer’s Row leader Babe Ruth), New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Postmaster General James A. Farley.

As part of a recent interview with Chris “Mad Dog” Russo on SiriusXM, Sandomir talked about Gehrig’s celebrated speech (a complete recording of which does not exist), comparing both the actual event and the re-imagined portrayal on celluloid.

“He certainly didn’t go to the microphone with anything in hand, which makes the speech all the more remarkable. He did it off the top of his head,” Sandomir said. “And Eleanor told at least four different stories about the genesis of the speech: They wrote it together; he wrote it himself; he rehearsed it; he didn’t rehearse it. Babe Ruth could have done a speech without a problem off the top of his head, but not Gehrig.

“At some point during the making of the film, Eleanor Gehrig, who was sending letters either through her agent Christy Walsh or directly to Sam Goldwyn [the film’s producer], was saying, ‘Here is the speech that should be rendered exactly like this for the movie.’ But the version that she gave is different in many ways from the way newspapers recorded the speech. Reporters certainly were not ready to transcribe the speech. Nobody expected Gehrig to make a speech and nobody was there to transcribe it as if it were a presidential address. The ‘luckiest man’ line is in different places. They weren’t ready for it or they took bad notes. I’m not really sure. Some of them had the ‘luckiest man’ line later on than it was. He delivered that ‘luckiest man’ line the second line in the speech. In the movie it’s the last line, moved for dramatic effect.”

Sandomir also shared a story of how the emotional impact of the speech played a role in the subsequent production of the Gehrig film.

“Perhaps the most important figure involved in the making of the movie is a fellow named Niven Busch, a writer who in 1929 was working for The New Yorker and he’s assigned to do a profile of Gehrig,” Sandomir said. “He goes to the Gehrig family house in New Rochelle. Gehrig was a quiet, withdrawn, not very sociable guy. So Niven Busch came away with a very bad impression of Lou, basically saying, ‘This guy doesn’t even deserve to have fans he’s so dull.’ Flash forward a dozen years later, Gehrig is dead, Busch is now a story editor for Goldwyn and he’s recommended the Gehrig story as a movie. Goldwyn says, ‘No, baseball is box office poison. You want to see baseball go to a game.’ That much he knew. He knew nothing else about baseball other than he would not make a movie about it.

“So Busch had another idea. He got a hold of the newsreel of Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day and he somehow persuaded Goldwyn to sit down in his screening room and watch it. He runs it once and who knows whether Goldwyn was fidgeting in his seat until he got to the end when the speech is made, because there is a lot of ceremonial stuff – the giving of the gifts, the speeches by Farley and La Guardia and Yankees manager Joe McCarthy. Finally he gets to the Gehrig speech. Lights go up after the speech is delivered. Goldwyn is crying. ‘Run it again.’ They run it again. The lights go up. He says to somebody there: ‘Get Mulvey on the phone.’ Jim Mulvey is his chief aid at Goldwyn Pictures. And he said, ‘Find Eleanor Gehrig. We’re going to make an offer.’ At that point nobody else had made a strong offer and Eleanor’s agent, Christy Walsh, was getting frustrated. Finally, Goldwyn comes forward with $30,000. Mind you, this all happens within six weeks of Lou dying. Lou’s dead on June 2, 1941, and the deal is announced on July 15.”

According to Sandomir, the speech didn’t spur Goldwyn; it was Gehrig’s death.

“I think it was the death that made it movie-worthy. It had to be tragic,” Sandomir said. “Because Gehrig on his own was not the most interesting guy. He was a great ballplayer but if Lou Gehrig had lived to be a ripe old age, no movie would be made about him. There would be no ‘Pride of the Yankees.’ What Goldwyn wanted was not baseball. He saw in that newsreel the story of a courageous man. Add that to the love story between Eleanor and Lou and that was the movie. There’s maybe 10 or 12 minutes of baseball action in the movie.”

On Dec. 7, 1939, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America voted unanimously to suspend the mandated five-year waiting period and elected Gehrig to the Baseball Hall of Fame immediately. Less than two years later, Gehrig died at the age of 37 on June 2, 1941.

Bill Francis is a Library Associate at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Lou Gehrig hits four consecutive home runs

Lou Gehrig appears in his 2,000th consecutive game for the Yankees

The Wright Stuff

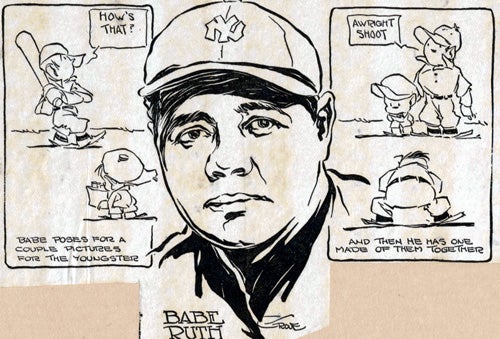

The Voice of Babe Ruth

Lou Gehrig hits four consecutive home runs

Lou Gehrig appears in his 2,000th consecutive game for the Yankees

The Wright Stuff