- Home

- Our Stories

- Lou Gehrig’s legacy celebrated every day at Hall of Fame

Lou Gehrig’s legacy celebrated every day at Hall of Fame

Lou Gehrig, who has been a constant presence at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for more than eight decades, remains a beloved figure to generations of fans.

With the news that Major League Baseball will celebrate Lou Gehrig Day on June 2, the date of his passing will become an annual celebration of his singular legacy.

The slugging Yankees first baseman is noted for his consecutive games played streak and remembered for his life’s tragic end due to a disease that would bear his name. His accomplishments and what he stands for as an icon of American sports culture have long been a pillar of the Hall of Fame’s guest experience.

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

“For more than 80 years, Lou Gehrig’s legacy has played a significant role in building the character of our National Pastime,” said Hall of Fame Chairman Jane Forbes Clark. “The Museum has been entrusted with the preservation of this legacy through generous donations of important artifacts that bring to life, and preserve, his heroic performances, inspiring sportsmanship, and his unmatched legacy of incredible courage. We honor Lou Gehrig, not only in our Hall of Fame and throughout the Museum’s exhibit areas, but also within our educational programming, where we use the example of his life to teach future generations important lessons of character.”

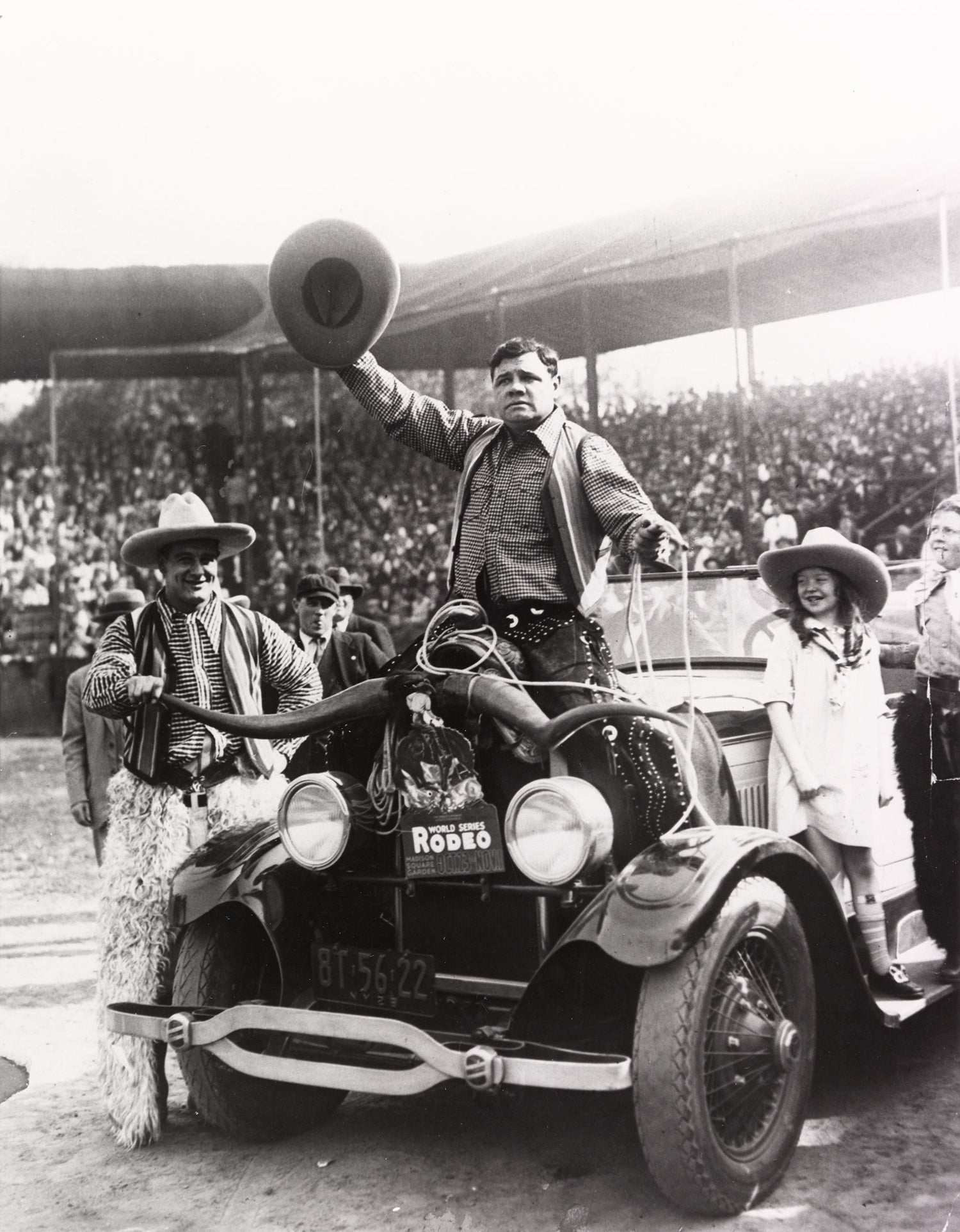

The name Lou Gehrig still conjures images of greatness, even though he played his last game in 1939. Teaming with Babe Ruth to form one of the game’s greatest offensive duos, Gehrig spent his entire 17-year career as a first baseman with the New York Yankees, helping the team to six World Series titles. During his illustrious career, he posted 13 consecutive seasons with more than 100 runs batted in and 100 runs scored, knocked in an American League record 185 runs in 1931, won the Triple Crown in 1934, and played in 2,130 consecutive games, a record that would stand until 1995 when Cal Ripken Jr. passed it.

As has been retold in numerous articles, television shows, books and movies, the end came suddenly shockingly for Gehrig. A slow start to the 1939 season ultimately resulted in the 35-year-old taking himself out of the lineup on May 2 after a then-record 2,130 consecutive games. Eventually, in mid-June he decided to put himself in the hands of the experts at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., to determine just why he had lost his baseball abilities so suddenly.

The Mayo Clinic’s report, in part, read: “After a careful and complete examination it was found that he is suffering from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis … The nature of this trouble makes it such that Mr. Gehrig will be unable to continue his active participation as a baseball player inasmuch as it is advisable that he conserve his muscular energy.”

“What my physical examination revealed came as a distinct shock to Mrs. Gehrig and myself,” Gehrig said at the time. “Before I went to the clinic I made a thousand guesses as to what might be the matter with me. What the tests showed was the one thing I never suspected. Mrs. Gehrig and I are fully resolved to face the situation calmly.

“It’s something to know what was wrong with me. I was sure that there must be some unrevealed reason why a man in such good general health as I enjoy should suddenly lose the coordination needed for playing baseball. Going to the Mayo Clinic was the best move I ever made.”

Gehrig even joked about the many physical examinations he underwent at the Mayo Clinic. “They even made an x-ray picture of my head,” he said, before adding with a grin, “but they didn’t find anything there.”

Later that summer, on July 4, 1939, Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day was held at Yankee Stadium, where Gehrig uttered the now famous and poignant words at a home plate ceremony: “Fans, for the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break I got. Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.”

On Dec. 7, 1939, the Baseball Writers’ Association of America voted unanimously to suspend the waiting period and elected Gehrig to the Baseball Hall of Fame immediately. The Hall of Fame’s first Induction Ceremony was held earlier that year, on June 12, 1939.

After Gehrig died at the age of 37 on June 2, 1941, the Hall of Fame announced that his plaque would be draped in black for 30 days and the flag at the Cooperstown shrine would remain at half-staff until June 15.

Less than two weeks after Gehrig passed, the annual Hall of Fame Game exhibition held at Cooperstown’s historic Doubleday Field between the Reds and Indians included a memorial to the lost legend. After bugler blew “Taps” before the contest, a tribute was read to the silent crowd.

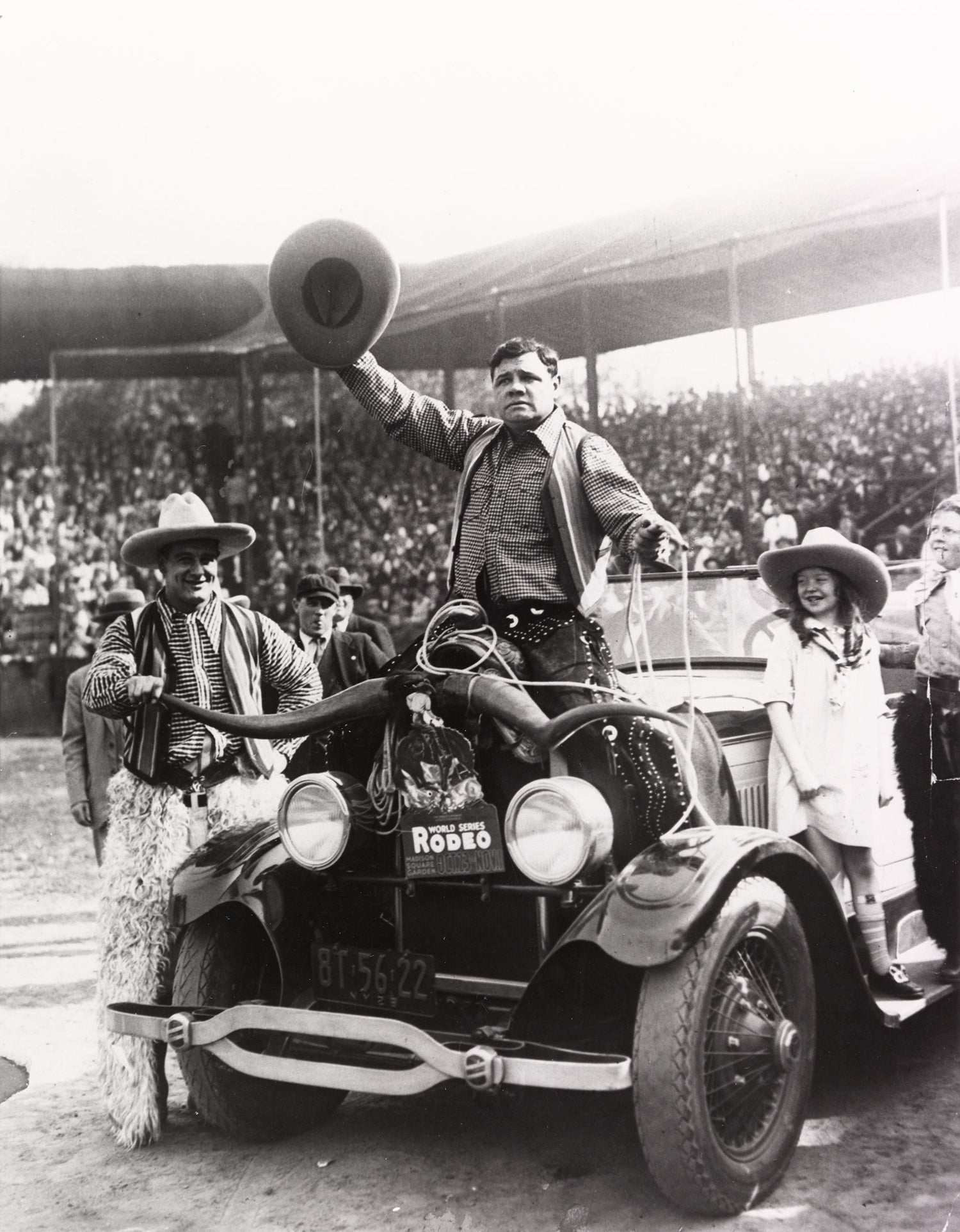

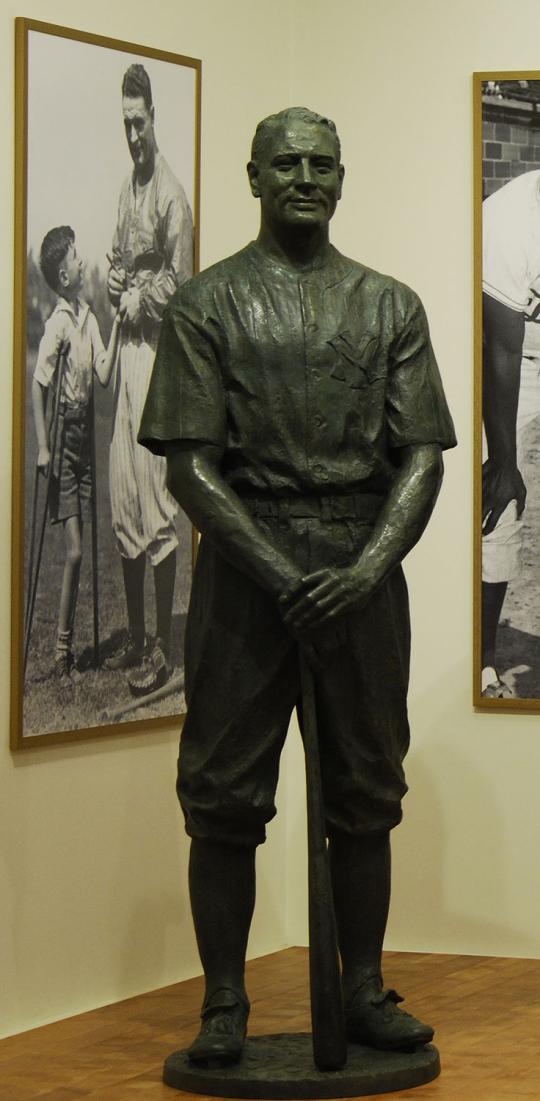

Today, a statue of Gehrig welcomes nearly 300,000 guests to the Hall of Fame every year. Standing alongside statues of Roberto Clemente and Jackie Robinson in the Museum’s foyer, these three works of art comprise the Hall of Fame’s Character and Courage presentation, celebrating individual stories of dedication, hard work and perseverance that continue to inspire generations of fans.

Walking through the Museum, Gehrig is featured in multiple exhibits, including the Timeline, One for the Books, Shoebox Treasures, Autumn Glory and Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend.

Thanks to the generosity of Gehrig, his wife Eleanor, his mother Christine, and others, hundreds of artifacts and library items are now a part of the permanent collection of the Hall of Fame.

Included among these donated Gehrig items, which help share Gehrig’s life on and off the field, his locker from Yankee Stadium; a mitt used circa 1932; the bat used during the 1937 All-Star Game to hit a home run off of Dizzy Dean; a trophy presented as a farewell gift to Gehrig on July 4, 1939 at Yankee Stadium from his Yankee teammates; a road jersey belonging to Gehrig from his final season in 1939; a bracelet Gehrig had made for his wife from gemstones from his awards; Gehrig scrapbooks compiled by his wife as well as the movie prop versions of these scrapbooks from “The Pride of the Yankees” film; and the official letter diagnosing Gehrig’s disease from the Mayo Clinic.

Arguably the most cherished item he was given on Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day, July 4, 1939, was this trophy from his teammates. On one side of the trophy were the names of all his current teammates; the other side a poem written by New York Times sports columnist John Kieran. According to Kieran, one day Gehrig pointed to the trophy from his teammates and said, “You know, some time when I get – well, sometimes I have that handed to me – and I read it – and I believe it – and I feel pretty good.”

The Hall of Fame also displays the Lou Gehrig Memorial Award plaque, which recognizes each of the annual winners of this prestigious award, created in 1955 and presented annually by the Phi Delta Theta International Fraternity to the big league player who best exemplifies the spirt and character of Gehrig, both on and off the field.

Through the Hall of Fame’s educational efforts, lessons of Gehrig’s character continue to influence young baseball fans. “Character Education: The Iron Horse” is one of 16 educational curriculum modules available for free on the Hall of Fame’s website and delivered to students both here in Cooperstown and across the country virtually.

Jonathan Eig, author of the 2005 bestseller Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig, may have explained Gehrig’s greatness the best.

“The entire 1938 season, you could make a case, was the most remarkable of all Gehrig’s challenges he had to overcome because he’s basically playing much, if not all, of the season with the symptoms of ALS,” Eig said. “I think it’s a type of courage to persevere and to keep yourself going and to never give up. Certainly when he’s facing symptoms of ALS he doesn’t know it yet. He’s clearly a sick man, a dying man, and he’s playing on.

“That’s some of the greatest courage that we’ve ever seen on a baseball field, in my opinion. I think it’s right up there with what Jackie Robinson did.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium

#Shortstops: Lou Gehrig’s gift

Trophy Gehrig presented his mother a part of Museum collection

Gehrig, Ruth round up funds for NYC hospital

Lou Gehrig Day at Yankee Stadium

#Shortstops: Lou Gehrig’s gift

Trophy Gehrig presented his mother a part of Museum collection