- Home

- Our Stories

- Larry Walker has been a Hall of Famer for years, thanks to Larry Doby

Larry Walker has been a Hall of Famer for years, thanks to Larry Doby

At the age of 18, Larry Walker was playing professional baseball with some of the best athletes in the sport. But this future Hall of Famer was not the Larry Walker recently elected to the Cooperstown shrine.

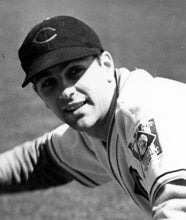

In 1942, Larry Doby was a senior at Eastside High School in Paterson, N.J. He was renowned in the area for his athletic prowess – dazzling teammates and opponents as a scholastic star in baseball, basketball, football and track. But to retain his amateur eligibility, the college-bound Doby took a unique summer job under an assumed name.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Acquiring a pseudonym to protect one’s amateur status was not uncommon in the first half of the 20th century, with legends such as Lou Gehrig and Eddie Collins taking on their clandestine monikers at one time. For the 18-year-old Doby – a left-handed batter and right-hander thrower – a chance to get paid while playing in the high-caliber Negro National League for the nearby Newark Eagles was an offer to good to pass up.

Doby was born in Camden, S.C., and soon moved to New Jersey with his mother. It wasn’t long before the teenager established himself in his new North Jersey hometown as an outstanding four-sport star.

The high school senior was feted and showered with accolades during the first half of 1942. In February, Doby was given a testimonial dinner at his church attended by more than 130 well-wishers. That winter he led the boys hoop team to postseason success. And in the spring – while also starring on a semipro baseball team – he participated on the high school baseball and track teams at the same time.

According to reports, Doby’s best year of high school baseball came in 1941 when he batted .559 for the season and was chosen an All-State first baseman. Selected as an All-State second baseman in 1942, he batted .400 that season.

“When a particular gent by the name of Doby is feeling good – woe be it to any team, barring none. Doby, in most people’s estimation, is the nucleus of the Ghost’s attack, and it is more than self-evident that he is,” wrote The Garfield (N.J.) Guardian in March 1942, referring to Doby’s play in the state basketball tournament. “When Eastside faced Garfield the second time out, Laughing Larry Doby, who doesn’t laugh when he’s performing, was the sparkplug as he singlehandedly maneuvered Eastside to a thrilling victory. A salute to Larry Doby, a ballplayer’s ballplayer on any club.”

With World War II raging in Europe and the future of professional baseball – segregated or not – in doubt, Larry Walker (alias Larry Doby), with his high school graduation still weeks away, made his professional debut as a ballplayer on May 31, 1942, at Yankee Stadium. This was despite many in Paterson thinking he was better at basketball than baseball.

With 17,000 in attendance for the Sunday afternoon Negro leagues doubleheader, the Baltimore Elite Giants took on the Philadelphia Stars in the opener and the Newark Eagles met the New York Cubans in the nightcap.

“Larry Walker, newcomer from Los Angeles, Calif., made his Negro National League debut with the Newark Eagles in Yankee Stadium last Sunday, poking a single on his second trip to the plate,” wrote the Baltimore Afro American after the Eagles’ 8-3 win. “He moved to second on Leon Ruffin’s bunt and scored as Leon Day got one of his safeties.”

This newcomer Walker (Doby) – who played third base, batted seventh in the lineup, and went 1-for-4 with a run scored in his pro debut – was given the fictional backstory that he was from California. But the Newark ball team he was joining was for real, led by future Hall of Famers Willie Wells, Ray Dandridge and Day.

A few days after his Eagles introduction, The Morning Call of Paterson, N.J., published this laudatory note: “Track lettermen at Eastside were announced yesterday, and when Larry Doby’s name was posted, it meant another chapter in the school’s athletic history being written by the Negro race. He is now the first four-letter athlete in Eastside’s history, having won varsity letters in baseball (3), basketball (4) and football (4). His total of 12 varsity letters is also a new school record.”

Amazingly, Doby, still just a high school senior, was soon gaining positive notices for the Eagles.

“The Newark club’s best known performers,” wrote the Dayton Daily News on June 11, 1942, “include right-fielder Ed Stone, centerfielder Lenny Pearson, shortstop and manager Willie Wells, third baseman Larry Walker and first baseman Francis Matthews.”

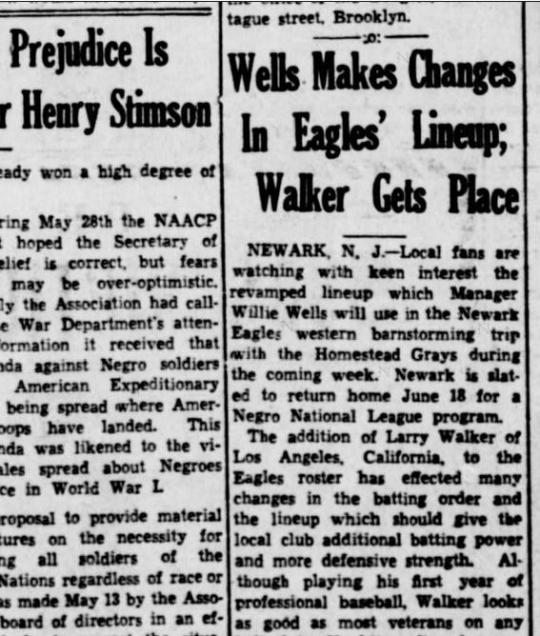

“The addition of Larry Walker of Los Angeles to the Eagles roster has effected many changes in the batting order and the lineup which should give the local club additional batting power and more defensive strength,” it read in the Chicago Defender on June 13, 1942. “Although playing his first year of professional baseball, Walker looks as good as most veterans on any ball club. He hits well and covers third base with marked confidence and enthusiasm.”

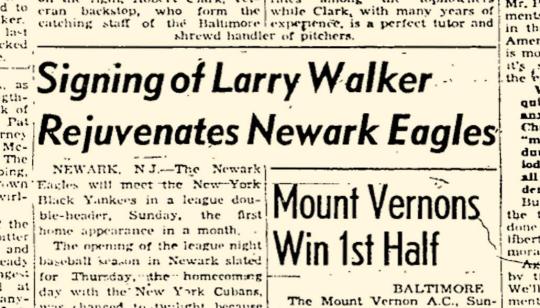

“When Larry Walker joined the team at Yankee Stadium two weeks ago, the Los Angeles, Calif., tosser was assigned to third base,” the Afro-American story of June 20, 1942, wrote under the bold headline Signing of Larry Walker Rejuvenates Newark Eagles. “He, incidentally, showed considerable hitting prowess.”

When it was time for Doby to finally accept his high school diploma – one of 334 Eastside High students to graduate – the local Paterson, N.J., newspaper, The News, wrote glowingly, “Included in the list is Larry Doby, brilliant Negro athlete. Doby, only Eastside athlete to ever win four letters (football, baseball, basketball and track), earned All-State recognition in all these sports except track.”

Soon enough, Doby had been moved by the Eagles to the outfield – the position he would eventually play in the integrated big leagues – and not skip a beat.

When the Homestead Grays hosted the Eagles for a doubleheader at Griffith Stadium on June 6, 1942, the Washington Post, in a preview of the Newark team, wrote, “The outfield is comprised of Larry Walker, prized rookie, and Ed Stone and Jim Brown, established veteran stars.”

Two months later, The New York Age on August 15, 1942, continued to sing the praises of the still misidentified Larry Doby: “Larry Walker, the new Eagles centerfielder, has become an overnight sensation. He plays the pasture post like a veteran and makes it look particularly easy. He hits well and has accounted for a major part of the locals hitting strength.”

By mid-September, with his college career looming, Walker was still gaining notices.

Doby would end that inaugural pro season, according to information provided by a National Baseball Hall of Fame-sponsored study and published Baseball-Reference.com, batting .333 (19-for-57) with three doubles, two triples, nine RBI and 12 runs scored.

After initially attending Long Island University to play basketball, Doby transferred to Virginia Union University in the winter.

But in the spring – and after receiving his draft notice – he was playing for the Newark Eagles again, only this time under his given name.

“Larry Doby is a youngster who starred for Paterson Eastside High School before joining the Eagles,” wrote The Morning Call on May 29, 1943. “He is a fine fielder, speed merchant on the bases, and has been hitting the ball at a terrific pace.”

By July 1943, though, Doby would by leaving for service in the armed forces, joining the Navy and finding himself at the Great Lakes (Ill.) Naval Training Station.

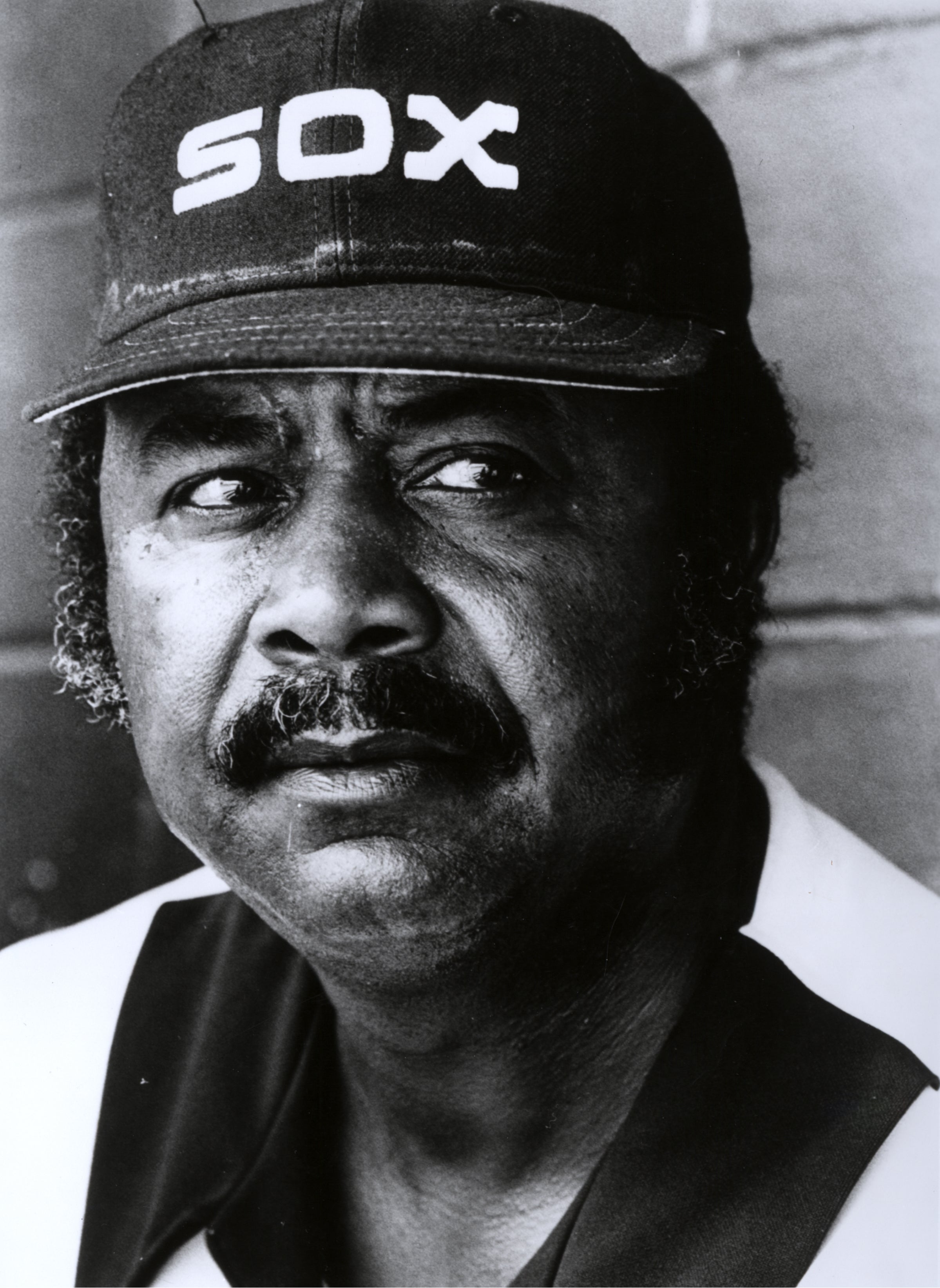

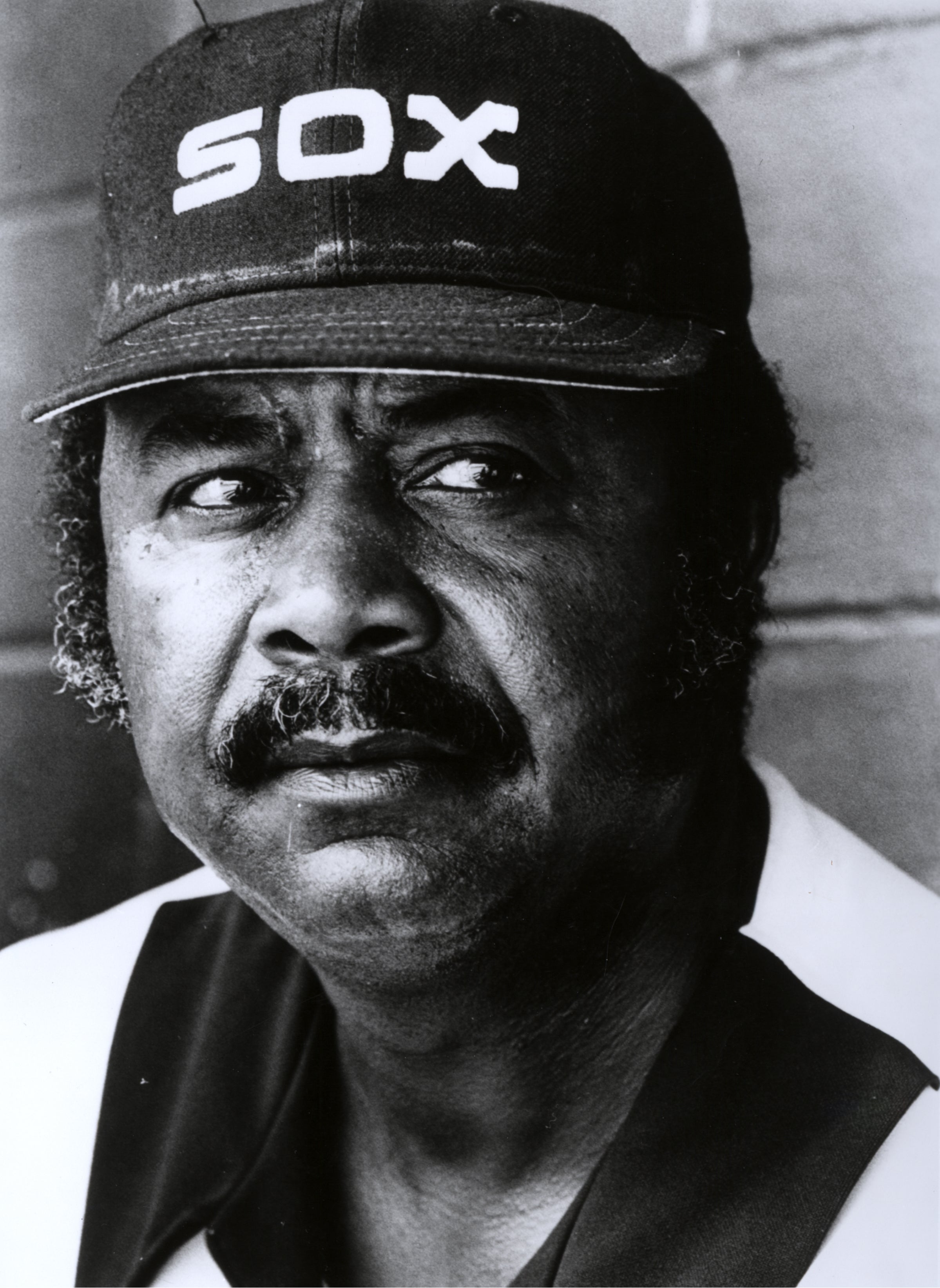

After three years in the service, the 22-year-old Navy veteran was discharged in January 1946 returned to the Newark Eagles late that year. In 1947, Doby made news across the country when on July 2 it was announced that Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck purchased the Negro Leagues star from the Eagles.

“The acquisition of Larry Doby is a routine baseball purchase – in my mind,” said Cleveland manager and shortstop Lou Boudreau. “Creed, race or color are not factors in baseball success whether it be in the major or minor leagues. Ability and character are the only factors.

“Doby will be given every chance, as will any other deserving recruit, to prove that he has the ability to make good with us.”

But before Doby left the Negro Leagues for good, he homered with his wife and mother in the stands in his farewell game with the Eagles on July 4. The next day he made his big league debut – only a few months after Jackie Robinson’s appearance with the Brooklyn Dodgers – to become the first African-American to play in the American League.

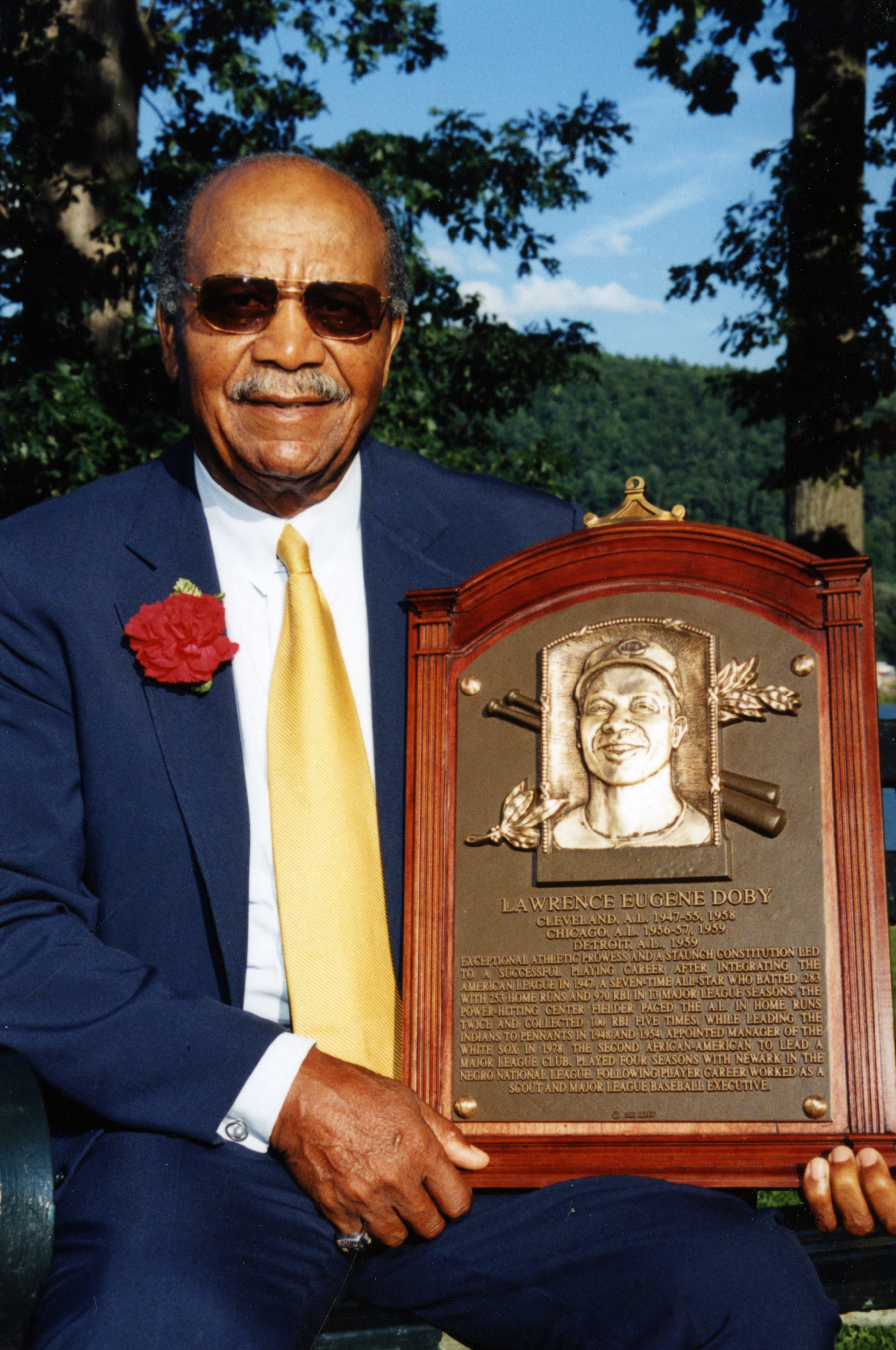

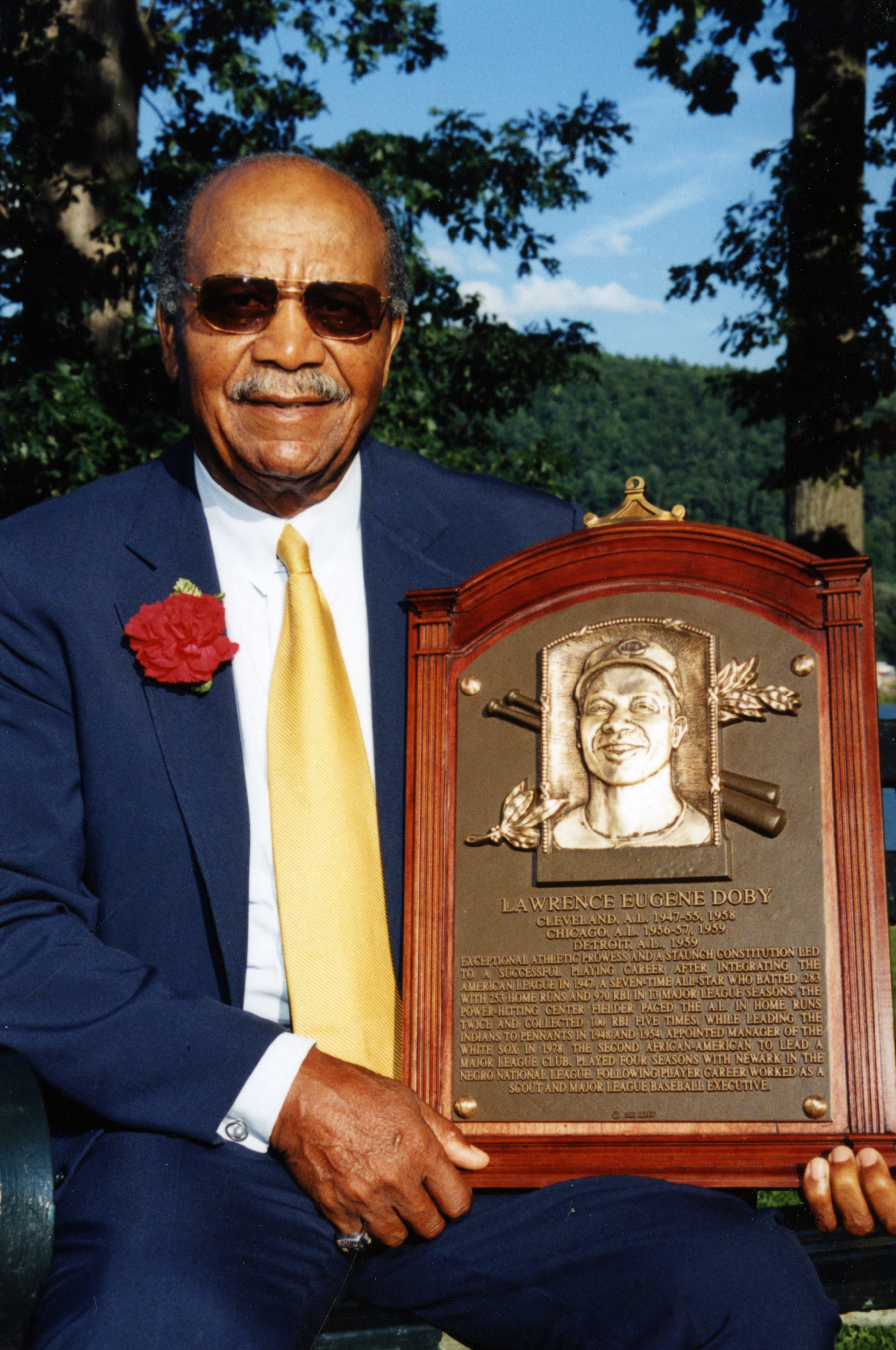

In 1997, 50 years after making his trailblazing debut with the Indians and a year before he was to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, Doby, a seven-time All-Star himself, was named the American League’s honorary captain at the All-Star Game in Cleveland. Colorado Rockies slugger Larry Walker was the Senior Circuit’s starting right fielder in that game on the way to a National League MVP Award winning season.

When Doby was asked about the irony, having once played under the name “Larry Walker,” he explained how his acquiring the name came about.

“To keep my scholarship, I couldn’t play pro baseball under my own name. My mother’s maiden name was Etta Walker, so my name with the Eagles was Larry Walker from June until September,” Doby said. “I never thought that name, Larry Walker, would pop up again.”

Doby would pass away on June 18, 2003, at the age of 79 in Montclair, N.J.

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Doby's pioneering path earned Hall of Fame plaque

Doby blazed trails on, off field

Doby made history with Indians

Veeck launches big league career by purchasing Indians

Doby's pioneering path earned Hall of Fame plaque

Doby blazed trails on, off field

Doby made history with Indians