- Home

- Our Stories

- Justino Clemente, brother of Roberto, visits Hall of Fame

Justino Clemente, brother of Roberto, visits Hall of Fame

Roberto Clemente’s life ended tragically more than four decades ago.

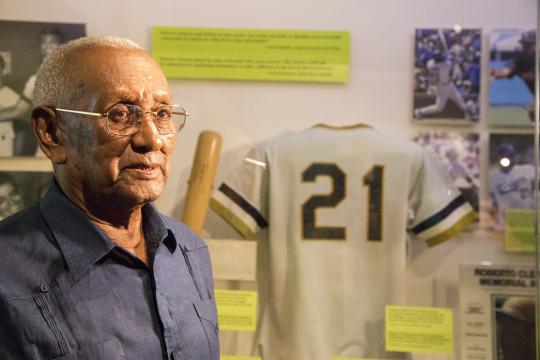

But thanks to the efforts of a fellow Hall of Famer, “The Great One’s” older brother and lone surviving sibling was able to visit the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for the first time – and help keep alive the memory of the Pittsburgh Pirates legend.

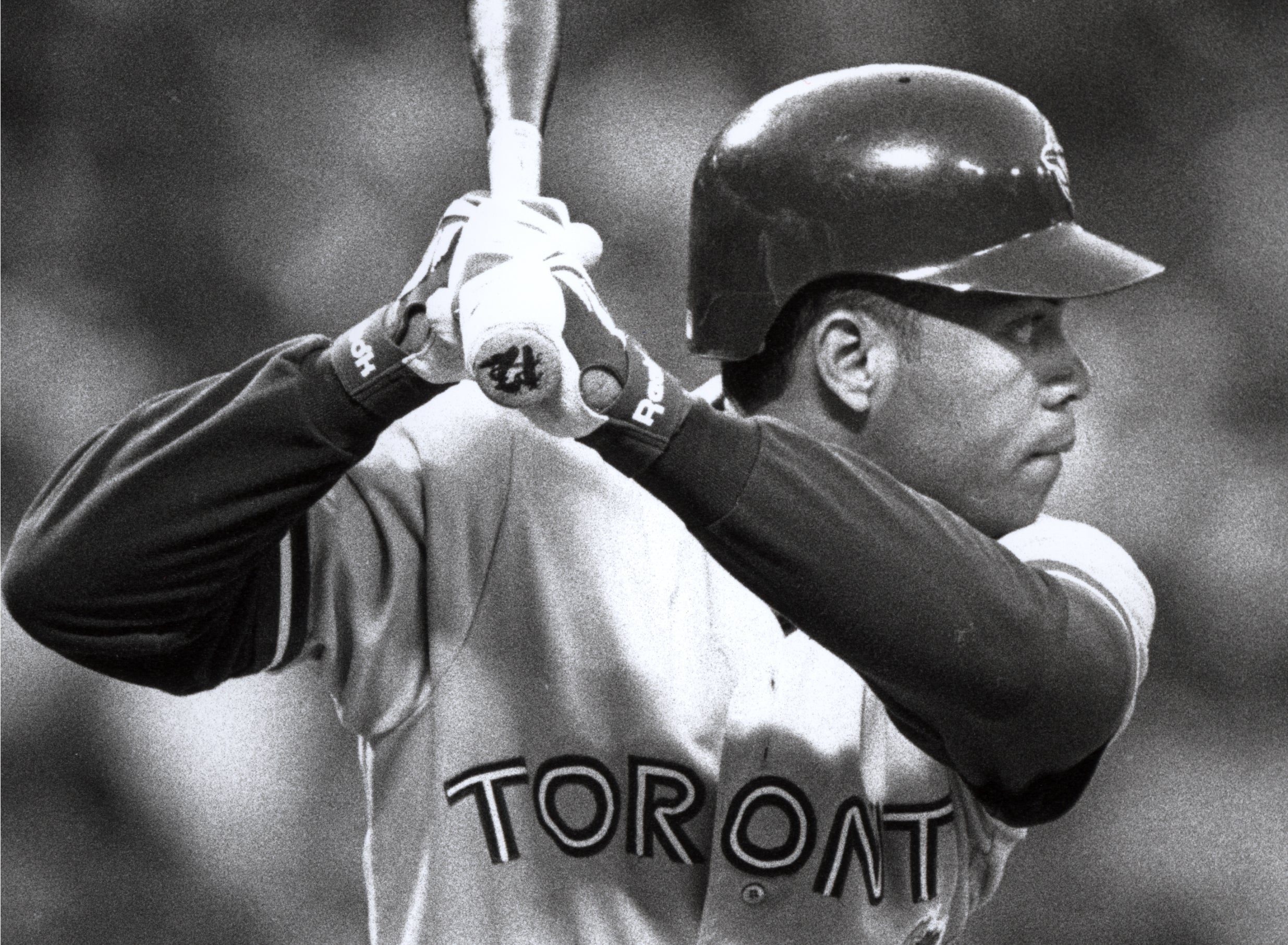

On Saturday afternoon, Sept. 29 – a day before the 46th anniversary of Clemente’s 3,000th big league hit – Hall of Fame second baseman Roberto Alomar, Class of 2011, and Justino Clemente, the 91-year-old brother of Roberto Clemente, participated in a Voices of the Game program in the Hall of Fame’s renovated Grandstand Theater. An hour prior, Clemente was apprehensive and emotional when first seeing his brother’s Hall of Fame plaque for the first time.

Alomar, Clemente, Orlando Cepeda and Iván Rodríguez are the only members of the Hall of Fame born in Puerto Rico.

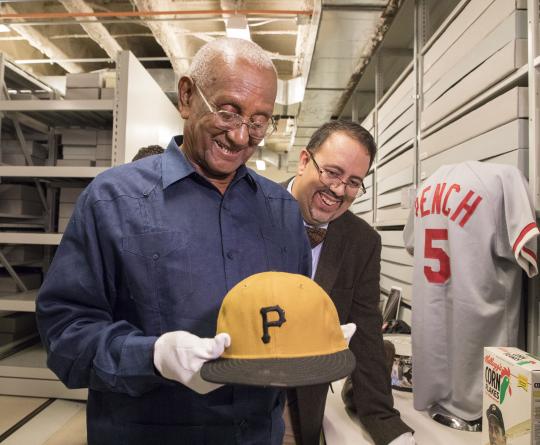

Justino Clemente, brother of Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente, holds the cap worn by Roberto when he recorded his 3,000th career hit on Sept. 30, 1972. Looking on is Adrian Burgos of La Vida Baseball, who served as Justino Clemente's interpreter during his visit to the Hall of Fame. (Milo Stewart Jr./National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The event, held in the midst of National Hispanic Heritage Month (Sept. 15-Oct. 15) and a month after what would have been Roberto Clemente’s 84th birthday, allowed the pair from Puerto Rico to share with the audience their recent journey of friendship that ultimately found them sharing a Cooperstown stage.

“He said it’s been a wonderful visit and it’s tremendous to be here,” said the Spanish-speaking Justino, translation on the stage provided by Dr. Adrian Burgos Jr., a history professor at the University of Illinois and the editor-in-chief of La Vida Baseball, a digital platform sharing stories of Latin Americans in baseball. “A lot of the work in getting here was done by Roberto Alomar arranging for him to be here and that in many ways he feels like he has gained a family member that has substituted for what he lost, and he wants to thank Roberto for bringing him and the family here.”

Thanks to the efforts of Alomar, Justino Clemente, usually called “Matino,” was accompanied on his trip to the Hall of Fame by wife Carmen and daughters Janet and Judy.

“To me, it is an honor to be able to bring him over here and to bring his family to join him at the Hall of Fame,” said Alomar, adding the two first met a year ago. “The way I met him, it was through a friend, after I found out that Justino always wanted to meet (me). That’s the only way I could meet him was through my friend. Finally I had a day where I could go and see him. I went to his house. I was impressed with his story about Roberto Clemente.

“I personally never saw Roberto Clemente play – I was too young – but Roberto Clemente for us is like God in Puerto Rico. I really appreciate what he has done not only for myself, but for all of those baseball players in Puerto Rico and other places in Latin America,” the 50-year-old Alomar added. “So I got to meet him (Justino) and one of his dreams was to come here so I promised him that I would take him here along with his family. And here we are.”

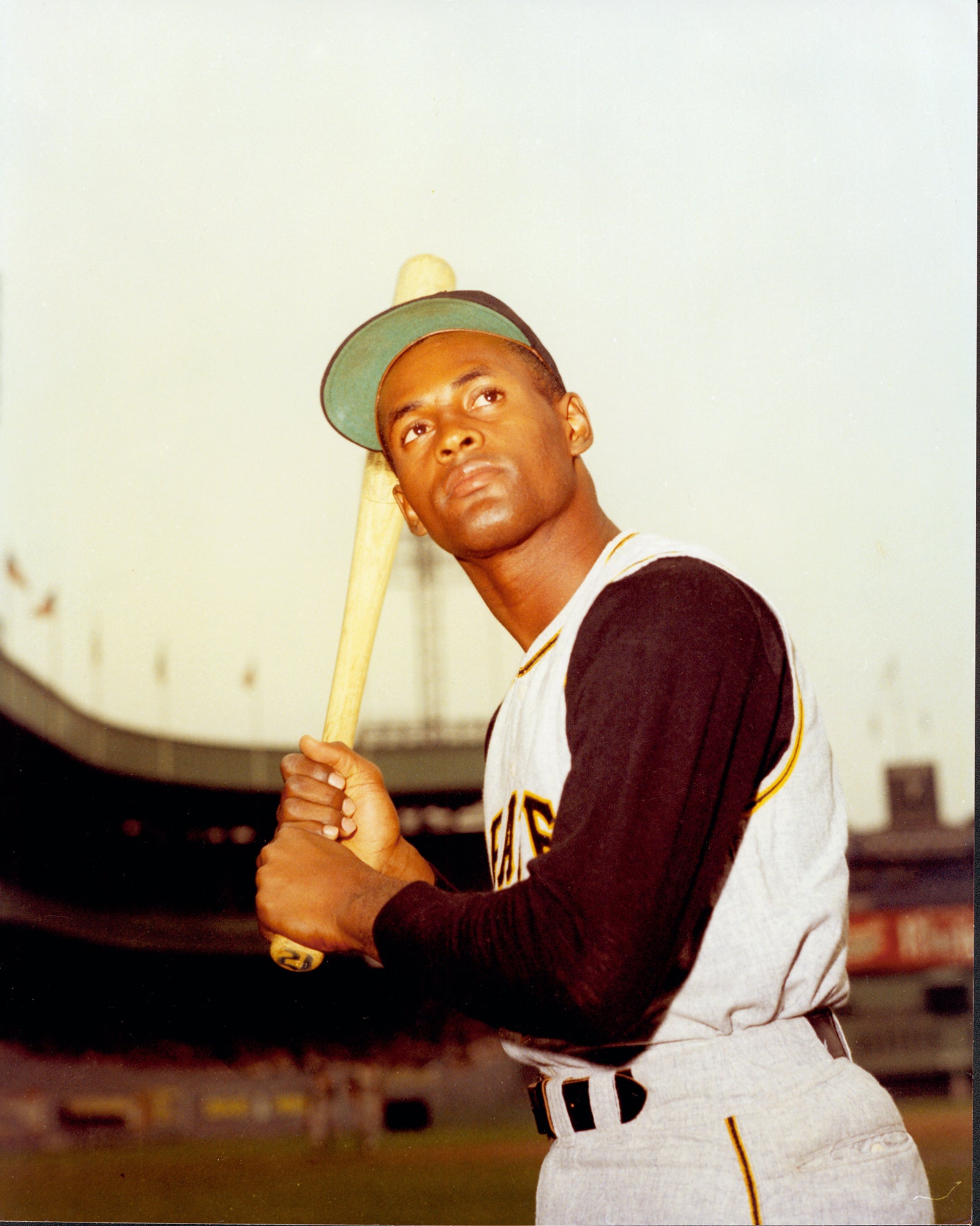

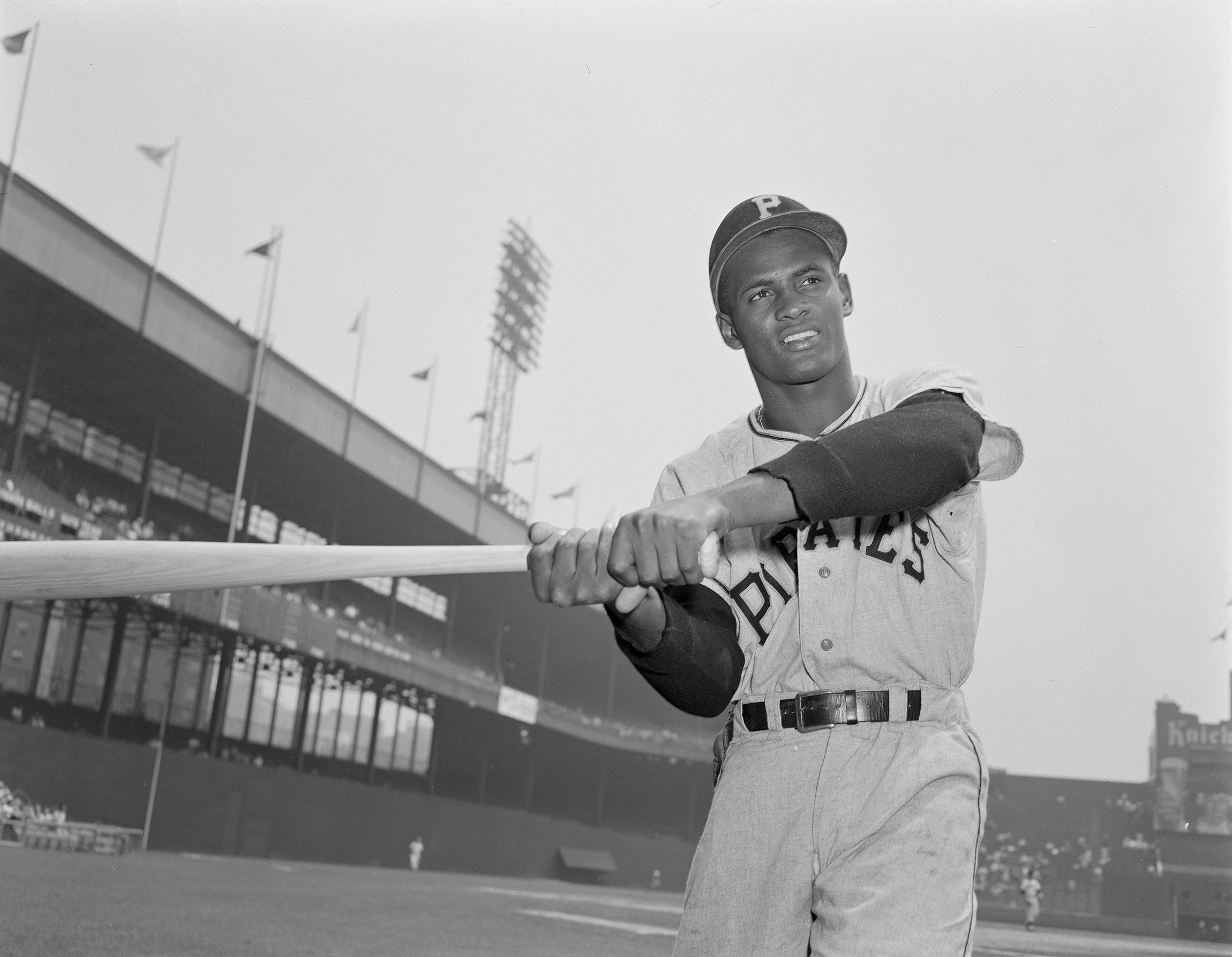

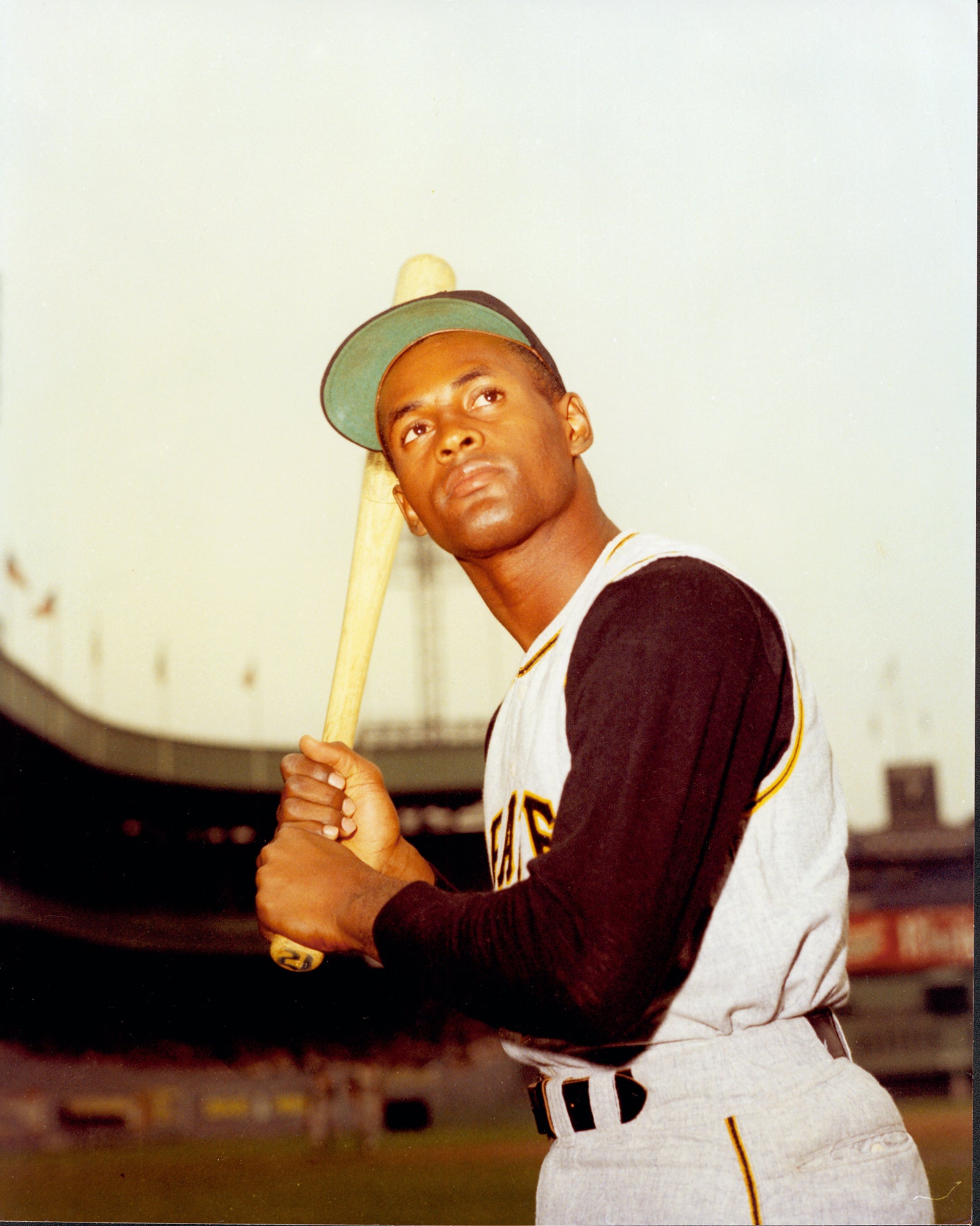

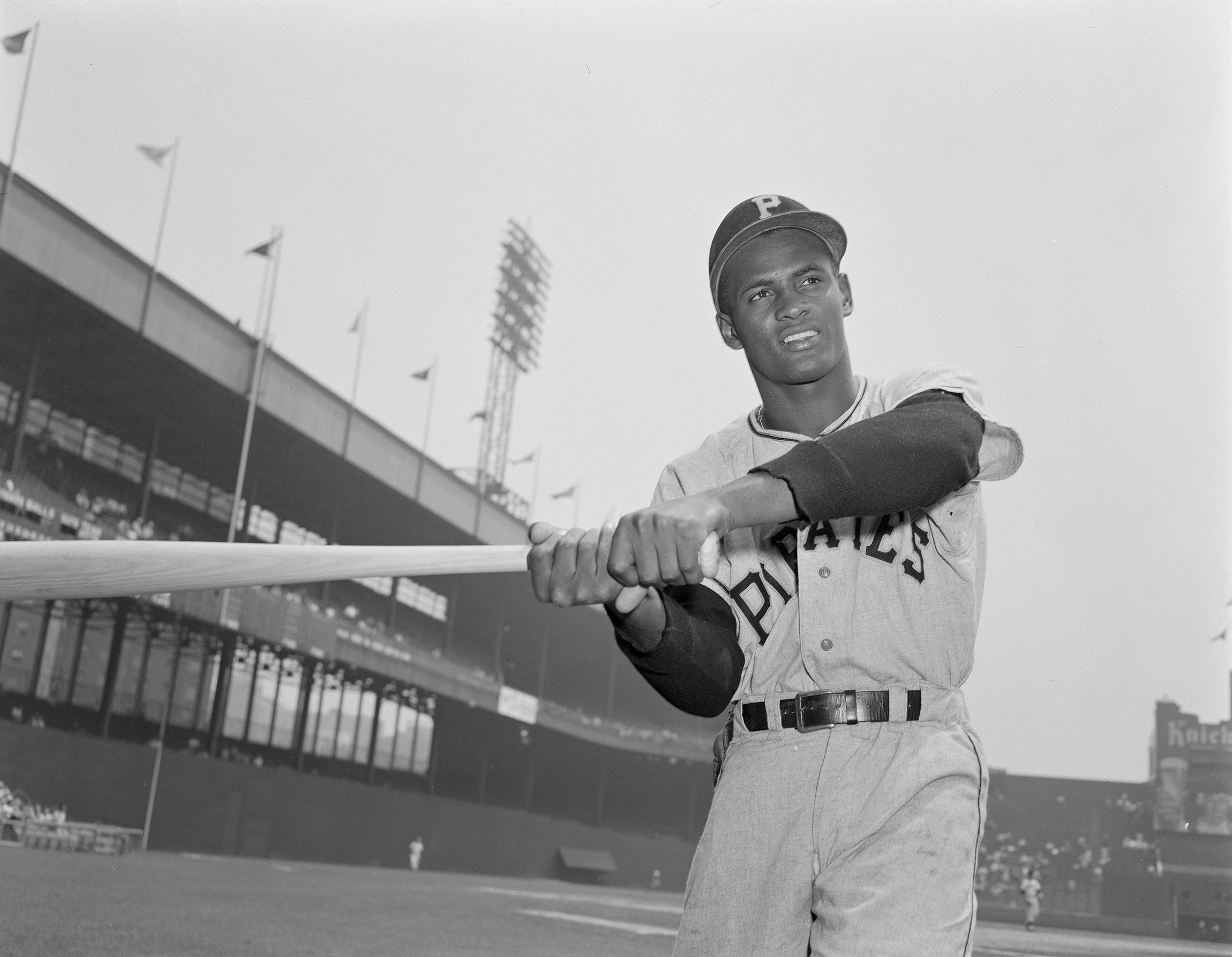

Clemente, a star right fielder with the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1955-72, died at the age of 38 on Dec. 31, 1972 when his plane delivering relief supplies to earthquake survivors in Nicaragua crashed at sea off the Puerto Rican coast soon after departing. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1973 – the first Latino enshrined – in a special election that waived the mandatory five-year waiting period.

Today, baseball’s Roberto Clemente Award is given annually to the player who "best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual's contribution to his team."

When asked if he was named after Clemente, Alomar initially demurred before admitting, “I don’t really know, but I’m going to say yes. They never told me. It is amazing how things worked out.

“I knew about Roberto Clemente when I was a kid. I remember when the incident happened, the tragedy of the plane, and I was four years old. I heard about it many, many, many times,” Alomar said. “But the amazing thing is that Roberto Clemente used No. 21 and I used No. 12. And he played the game one way, I played the game a different way, and we both now are in the Hall of Fame. I’m honored to be named Roberto. Roberto Clemente for us was an inspiration for not only the Puerto Rican people, but for all the Latin players.

“I’ll always respect Roberto Clemente for what he did on the field, but I respect him more for what he did off the field. A lot of people don’t talk about that. A lot of people know him as a great ballplayer, but he was a better person away from the game. I learned how to be who I am today from him – giving back to the community, giving back to the youth – so I’m following in his footsteps. I’m never going to be like him – nobody can be like him – but at least I can follow and I can try to simulate what he did.”

Asked what Roberto Clemente – the youngest of eight siblings – was like, Justino Clemente, seven years older than his Hall of Fame brother, shared stories about their life growing up together in Puerto Rico.

“He’s saying that Roberto started playing baseball when he was 8 or 9 years old and he would be with his brother all the time, but that one of the important things was the lessons that their father taught them,” Burgos relayed. “He told them that you are the equal of everyone and everyone is the equal of you regardless of color, regardless of background. That was a very important lesson that they learned.

“And he said their father also told them as they started playing baseball to always set an example and that if you are ever to become famous don’t forget to be the same that you were before – treat everybody well and everyone will respect you,” he added. “Their father couldn’t read and couldn’t write, but he raised them so that they would know how to conduct themselves and be an example to others.”

Justino Clemente then told a humorous anecdote about their father’s eventual love of baseball.

“Their father did not know anything about baseball, so they learned the game themselves. Their father didn’t teach them anything,” Burgos translated. “And so Roberto was playing and he went to a game between San Juan and Santurce. Roberto hits a home run and their father asked him, ‘Why is Roberto running around the bases like that?’ And so Justino explained that Roberto hit the ball on the other side of the fence and it’s what he gets to do.

“In the course of one season, by the end of that season, he knew hit-and-run, he knew about scoring position, what a dead ball meant. He was an expert by the end of that one season watching Roberto play.”

Justino Clemente would go on to say that his brother was taken aback by the treatment he received playing pro ball.

“Roberto as a young kid was kind of reserved and he took things to heart sometimes, but he was someone who liked being with people,” Burgos translated. “But his experience in the United States dealing with the racism really affected him quite a bit and it changed his personality. He became more guarded. When the press would come in the locker room he would try to hide. What Roberto would be wary of was would they be translating exactly what he was saying to the public or would they twist his words.

“Roberto would communicate with him and talk about some of the things that really bothered him. One of the main things was how in many instances the team would go out to eat somewhere that Roberto would have to stay behind on the bus because they didn’t serve black people. Roberto, as he became a bigger and bigger player, a bigger star, started telling the younger players on the Pirates we shouldn’t eat there if we all can’t eat together.”

Justino Clemente, a talented amateur ballplayer in his own right, would also help his brother when he was slumping.

“Roberto and Justino talked quite a bit,” Burgos said. “When Roberto was a major leaguer, they would talk over the phone and their father would actually tell Justino to go and help your brother and would send him to wherever Roberto was playing.”

On a private tour of the Museum’s collection storage area prior to the Voices of the Game event, Justino Clemente was shown a number of artifacts related to his brother, including a medal, a game ticket, the cap Roberto wore when he collected his 3,000th career hit, and even a cereal box with the Pirates star’s image on the front. But it was a 1952 Clemente contract to play Puerto Rican Winter League baseball with the Santurce Crabbers that surprised everyone when Justino admitted he that signed it instead of his father.

“Their father could not read or write so he couldn’t sign and so they brought the contact to him and at first he hesitated in signing it because he was thinking about Santurce already having Willard Brown, Bob Thurman and Buster Clarkson,” Burgos translated. “He was thinking is his brother really going to get a chance to play and he hesitated in signing. And another Puerto Rican player, Monchille Concepcion, brings the contract and basically puts it on his lap and says, ‘That’s between you and your family and you have to make a decision.’ And finally he says, ‘I’ll sign it,’ and he signs it.”

By the end of the day, Alomar talked of this year-old relationship with Justino Clemente that has blossomed.

“When I went to meet him for the first time I told his family that I could only be there for 10 minutes, thinking he was 90 years old and wouldn’t talk a lot. I stayed in his house for two hours talking about baseball,” Alomar said. “He has an amazing memory, loves talking baseball, and you can hear the stories about what Clemente had to go through in those days. I had a father, too, who played the game (former big leaguer Sandy Alomar Sr.), and my father went through a lot of tough times, the same way that Roberto did. And I went through some tough times, but not as tough as him.

“We will go through struggles in life, but if you are good to people, not matter the color, no matter what you come from, you can make a difference doing what you do. I couldn’t meet Roberto Clemente, but now, through him (Justino), I can feel Roberto Clemente and I can learn a little bit about his life. I cannot thank him enough for letting me be a part of his family.”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

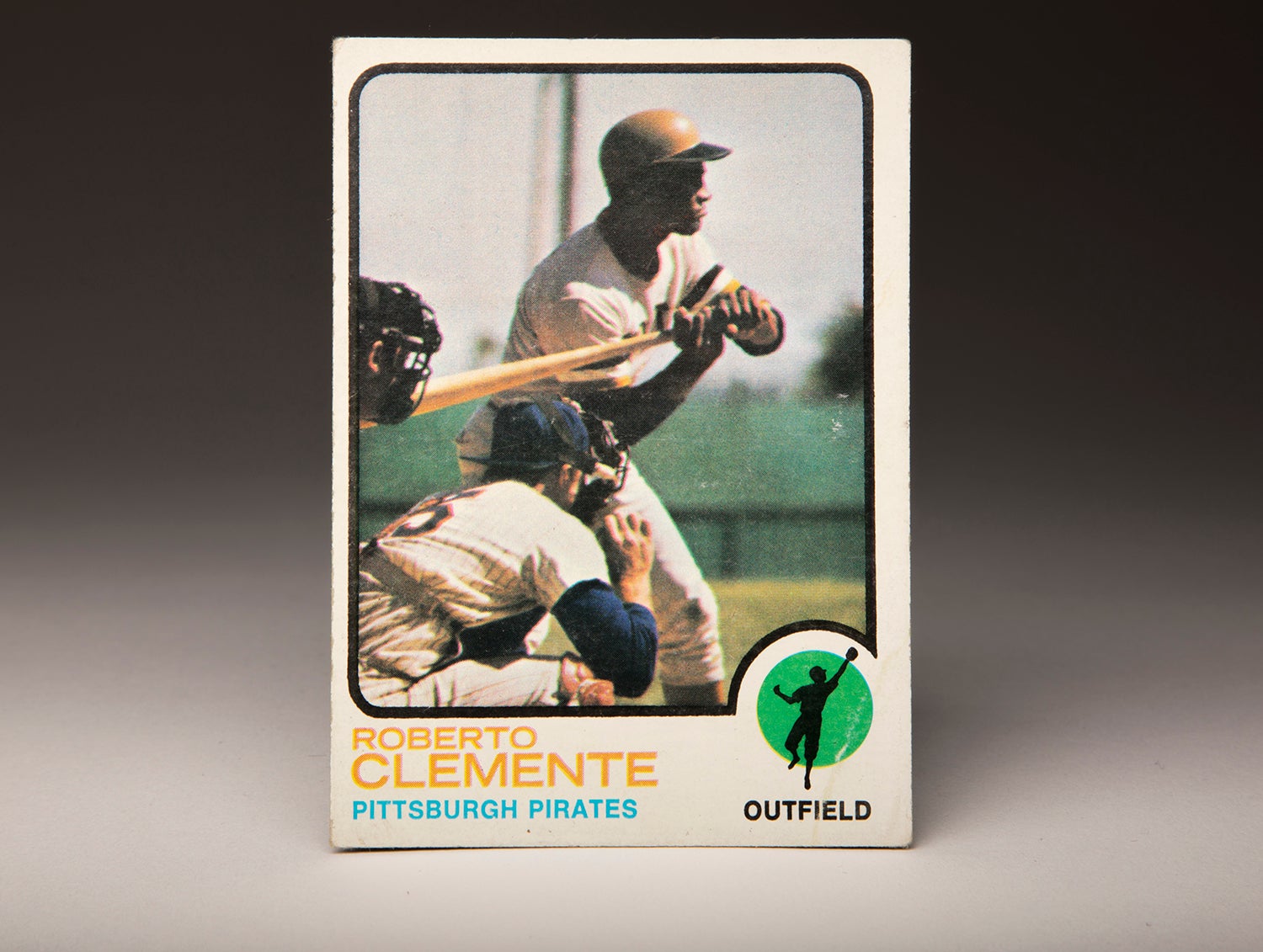

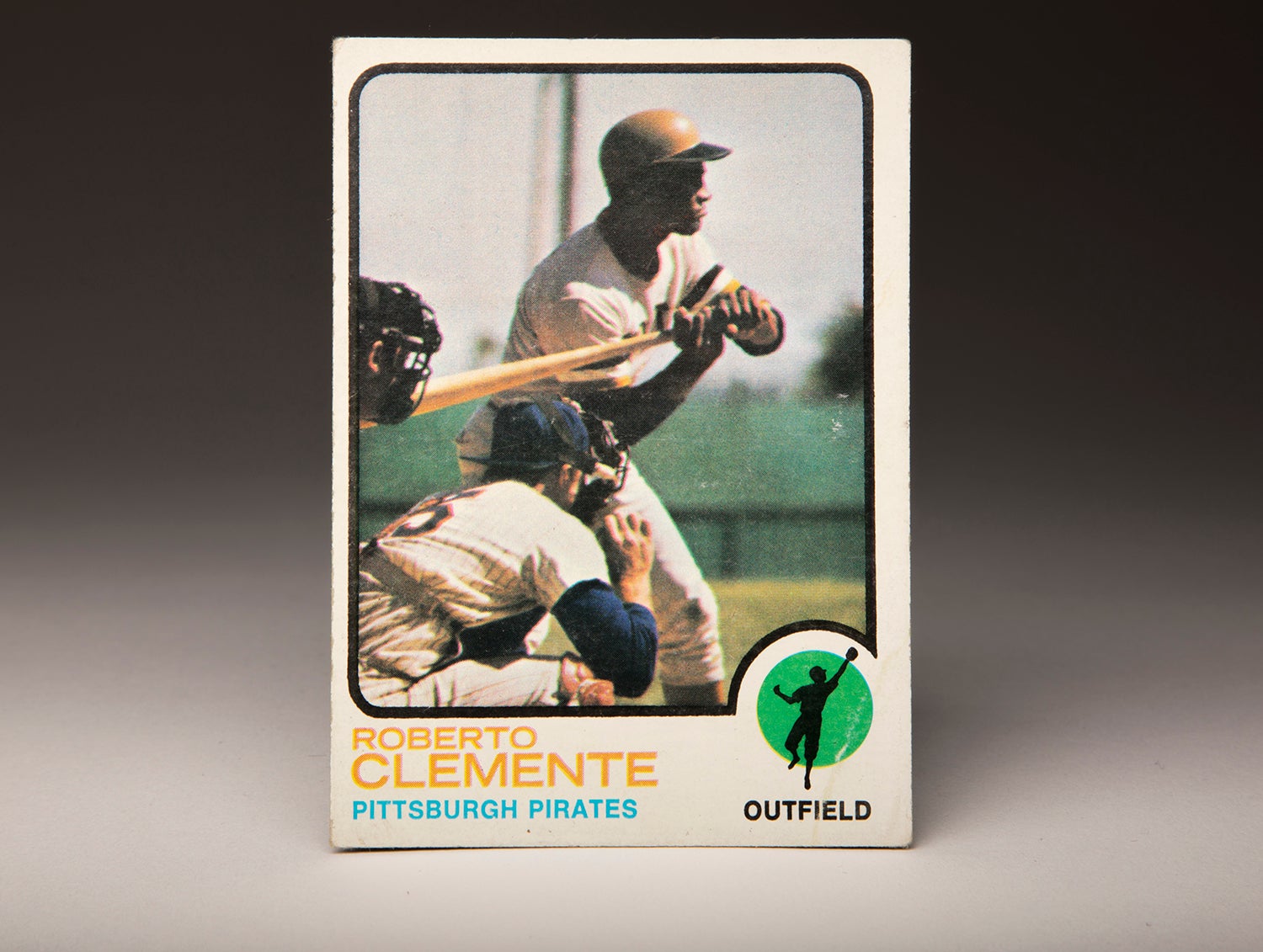

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Roberto Clemente

Roberto Clemente records 3,000th hit in final regular-season at-bat

Roberto Clemente named 1966 NL MVP

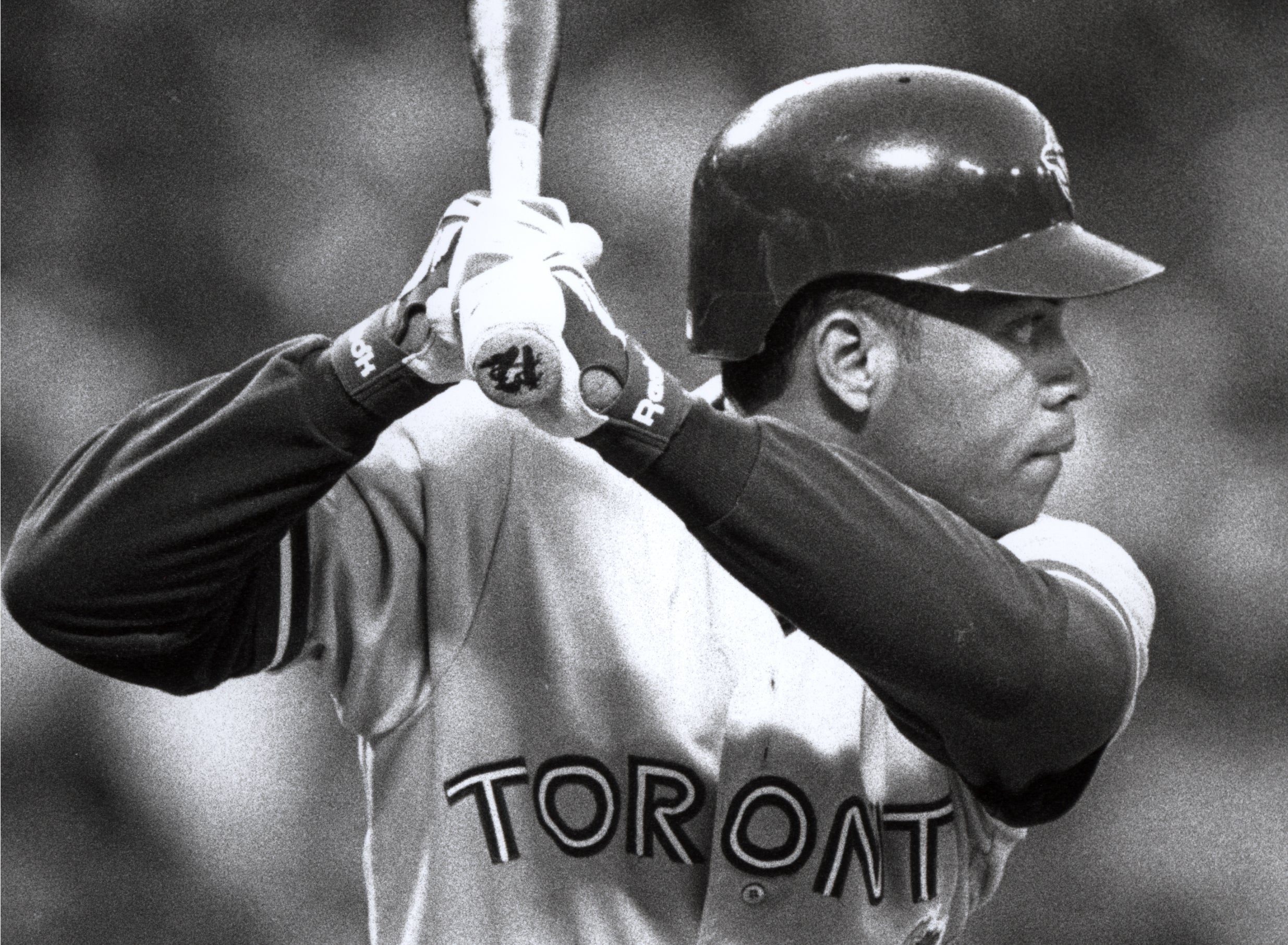

Roberto Alomar recalls his Game 4 1992 ALCS home run

#CardCorner: 1973 Topps Roberto Clemente

Roberto Clemente records 3,000th hit in final regular-season at-bat

Roberto Clemente named 1966 NL MVP