- Home

- Our Stories

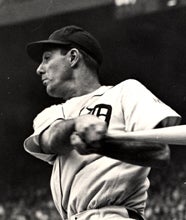

- Tigers move first baseman Hank Greenberg to the outfield

Tigers move first baseman Hank Greenberg to the outfield

By February of 1940, Hank Greenberg was one of the biggest stars – and best hitters – in the game.

From 1933-1939, the Detroit Tigers first baseman averaged .324 and led all of baseball in home runs twice during that span, falling just three short of eclipsing Babe Ruth’s record of 60 in 1938. The year before, he drove in 184 runs – still the third-best single season total of all time.

As Spring Training 1940 inched closer and closer, the last thing Greenberg needed to prove was that he could hit.

But by demonstrating his ability to transition from first base to the outfield, Greenberg provided the key to unlocking an American League pennant for the Tigers.

On Feb. 15, 1940, Tigers manager Del Baker and general manager Jack Zeller informed Greenberg that he would be shifting from first base, a position he had played for the past seven seasons, to left field. It was their attempt to solve a long-standing conundrum within the organization: Where to play Rudy York.

York, a fellow slugger like Greenberg, had tried his hand at playing the outfield and behind the plate. But the best fit for York, it seemed, was at first base.

And like Greenberg, he was too powerful of a hitter to remove from the lineup.

Fortunately, Greenberg was never one to shy away from a challenge.

“I didn’t have to move off first base,” he clarified to reporters. “Mr. Briggs and Del Baker asked me if I was willing to make the shift. They didn’t tell me to. I didn’t have to give it much thought. Any kind of a move that could keep both Rudy York and myself in the batting order would be a great help to the club. Rudy is convinced he can’t play the outfield, but can play first base. That put it strictly up to me to move to the outfield if I wanted to help the club.”

In 1940, Hank Greenberg would become the first baseball player to win two MVP awards at two different positions: first base and left field. (National Baseball Hall of Fame)

Share this image:

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The transition wasn’t flawless for Greenberg. He had to switch from using his “scoop shovel” first baseman’s mitt to an outfield mitt. He had to teach himself the long follow-through of an outfielder’s throw, as opposed to snapping the throw with his wrist as he had done before. And he had to get used to running more frequently, since he would be responsible for covering all of left field. But he understood what was at stake, and Greenberg’s dogged work ethic hastened the learning process for him that season.

“I’ve always had a high opinion of any athlete who isn’t afraid of hard work and who drives himself in a constant search for perfection,” said Fred Haney, former manager of the St. Louis Browns. “That morning Hank phoned me [before we played the Tigers]. ‘Fred, he said. I’d appreciate it if you’d let me borrow your field early so that I can get in some practice as an outfielder.’ He worked for hours, shagging flies and judging line drives caroming off the fence.”

Greenberg’s hard work paid off. By the end of the season, his fielding percentage only saw a slight dip, from .993 the year before to .954. He led all American League leftfielders in putouts (298) and assists (14), and won his second AL Most Valuable Player Award in six years, becoming the first baseball player in history to win two MVP awards at two different positions.

Offensively he remained untouchable, leading the league in home runs (41) and RBI (150). Under Greenberg’s lead, the Tigers won the AL pennant that year, and narrowly missed winning the World Series, falling 4-3 to the Cincinnati Reds.

But to Hank, it was as simple as just doing his job.

“I didn’t want to embarrass myself or the ball club,” he said to The New York Times. “If I had been a businessman, I would want to protect my investment. As a ballplayer, I had to protect the only investment I had, my physical skills. When I was a kid in the Bronx, I played ball eight hours a day for nothing. But when I was being paid to do the same thing, the least I could do was give my employer full value for his money.”

Alex Coffey was the communications specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

The Return of Hank Greenberg

Goslin’s walk-off clinches Tigers’ first title

The Return of Hank Greenberg