- Home

- Our Stories

- Feller, Robinson make history with Hall of Fame elections

Feller, Robinson make history with Hall of Fame elections

In the 27 years following the first Hall of Fame election in 1936, no first-year candidate had earned a place in Cooperstown.

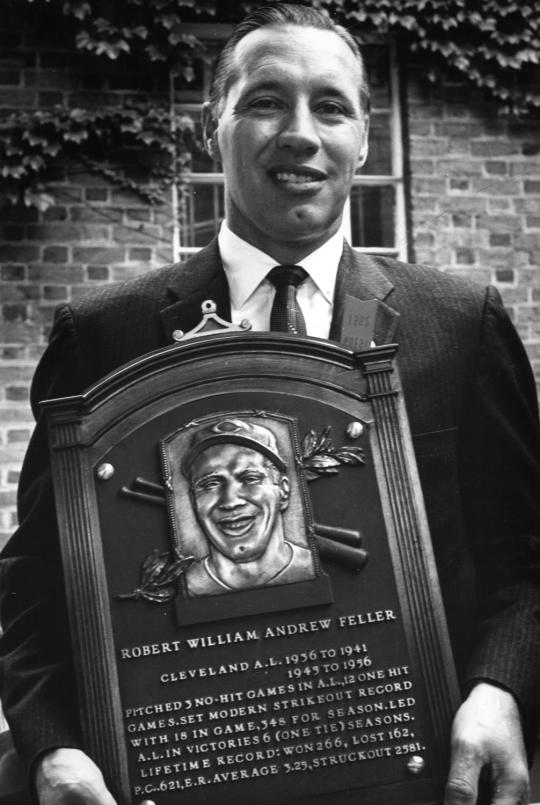

On Jan. 23, 1962, Bob Feller and Jackie Robinson – two men accustomed to blazing new trails – once again broke new ground, earning Hall of Fame induction in their first try on the Baseball Writers’ Association of America ballot.

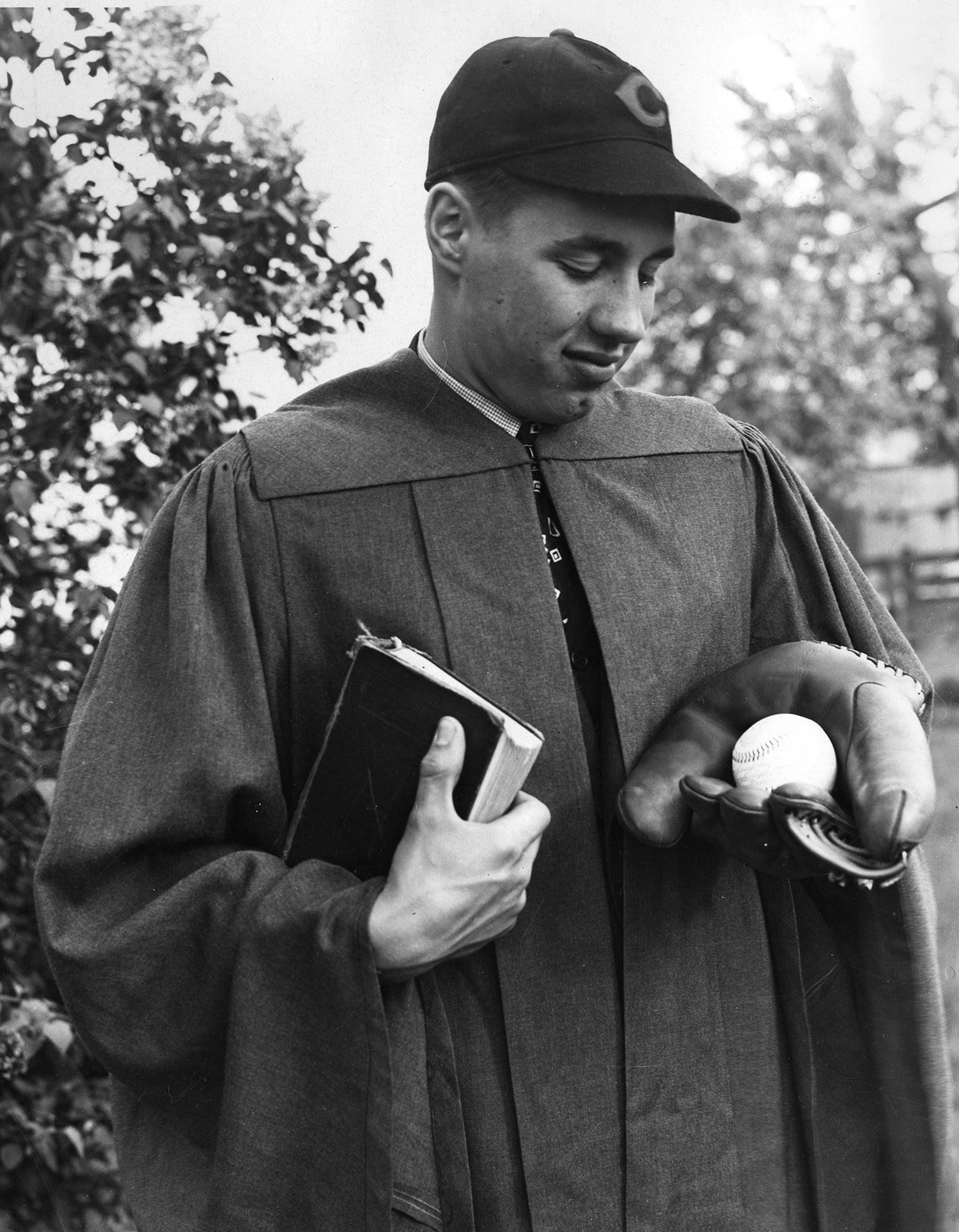

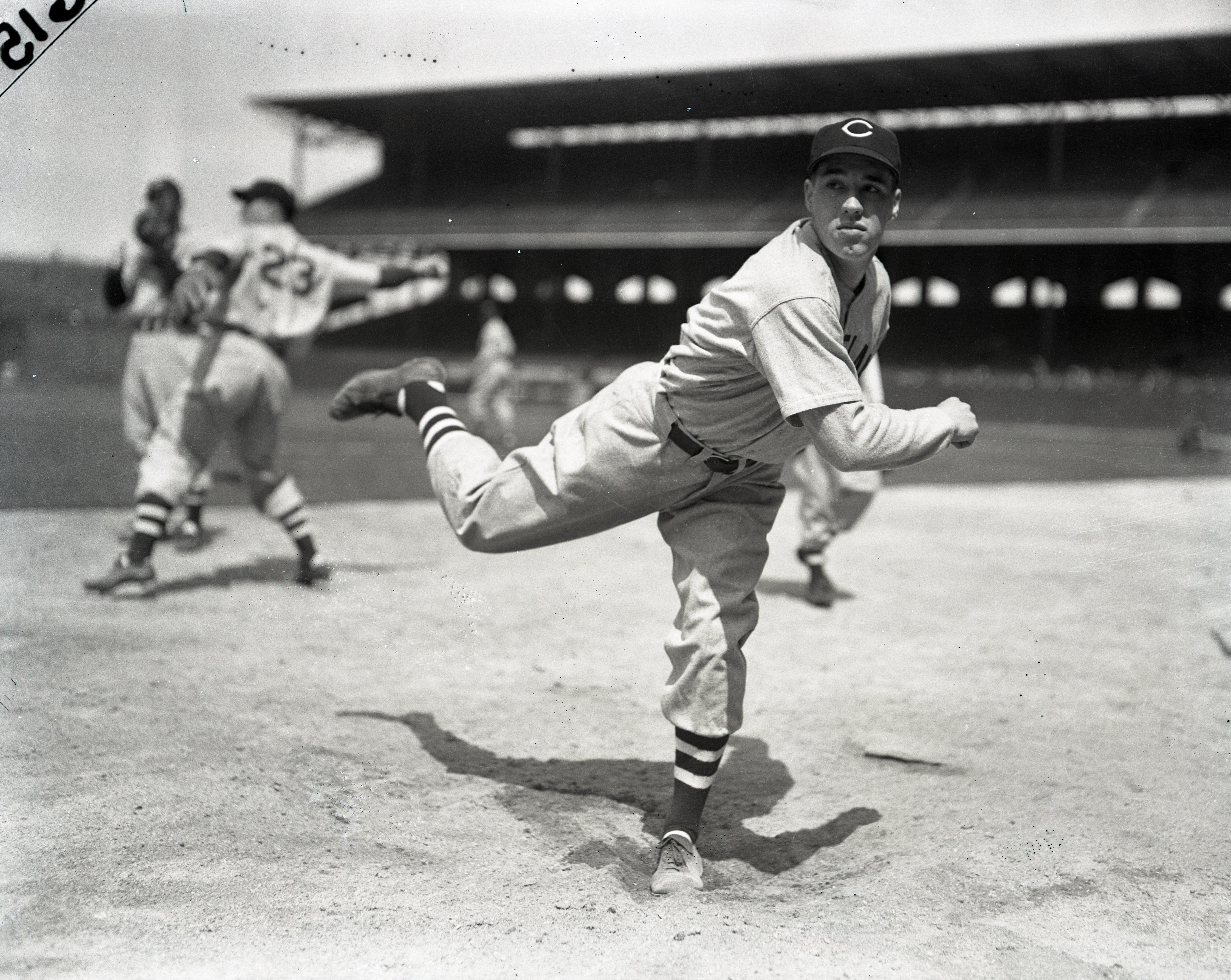

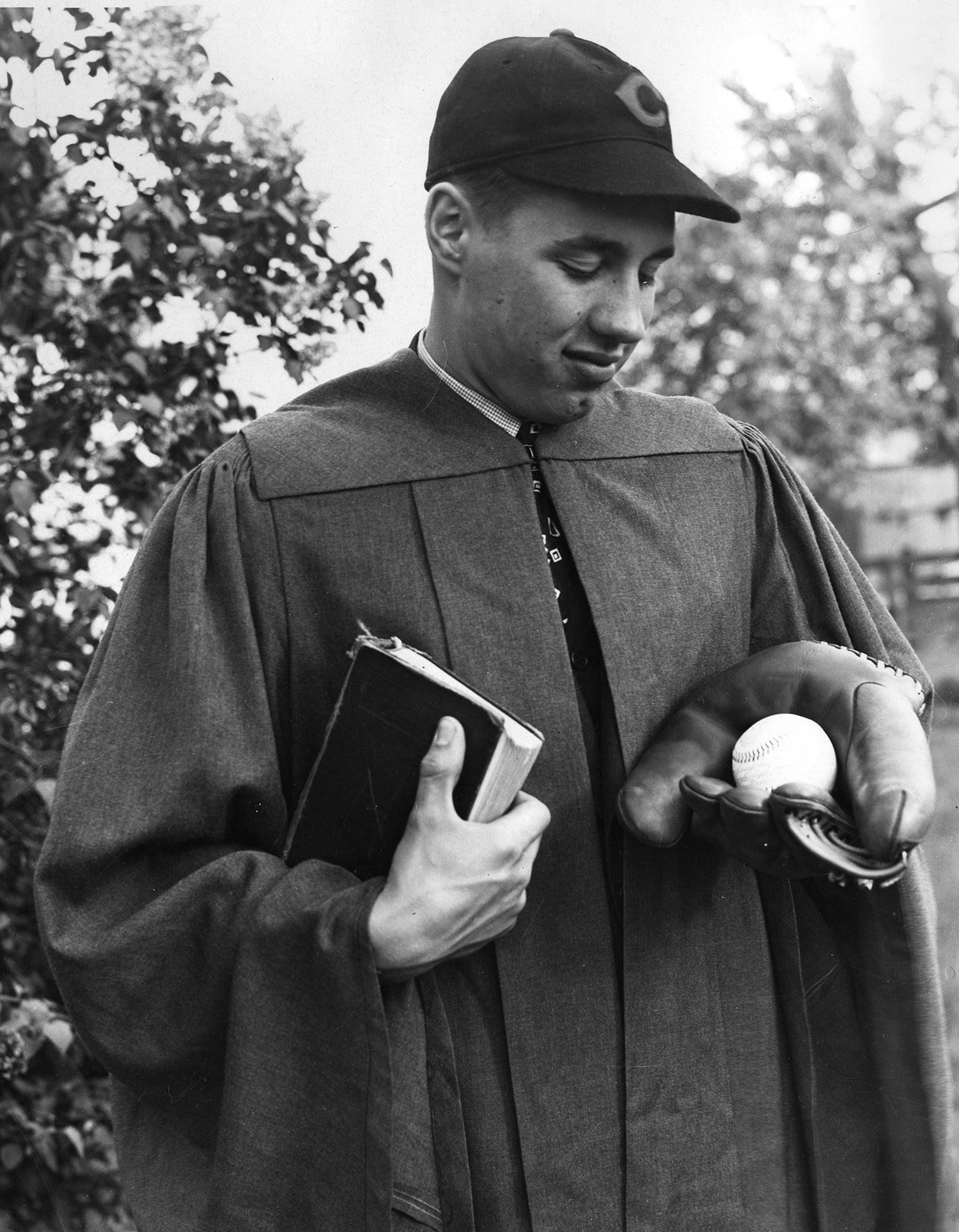

Feller and Robinson each retired following the 1956 season, and each rose to the status of cultural icon during their career in the big leagues. Feller broke into the majors in 1936 as a fireballing 17 year old – and became so popular that his high school graduation was broadcast on national radio.

By the end of the 1941 season, Feller had amassed 104 wins and three 20-victory campaigns. But the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, Feller enlisted in the Navy – spending three-and-a-half years serving his country in active duty.

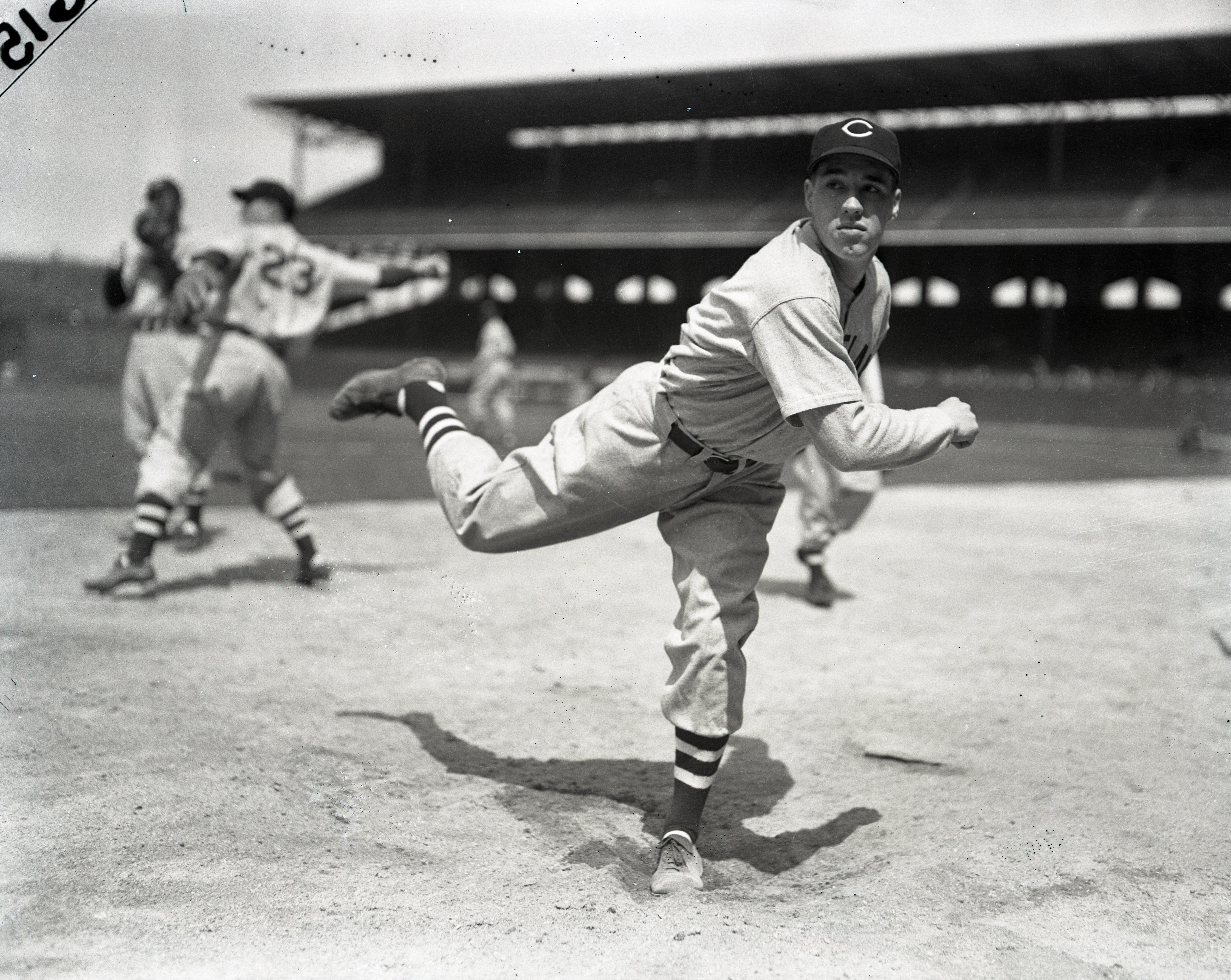

When he retired, Feller had totaled 266 wins and 2,581 strikeouts. He was named on 93.8 percent of the Hall of Fame ballots in 1962, the fourth-highest percentage ever at the time.

“It wasn’t until you hit against him,” said Hall of Fame pitcher Ted Lyons. “that you knew how fast he really was… Until you saw with your own eyes that ball jumping at you.”

Robinson became the first African American to appear in a modern big league game when he broke the color barrier on April 15, 1947 for the Brooklyn Dodgers. As a rookie during Feller’s ninth big league season, Robinson hit .297 with 125 runs scored and a National League-best 29 stolen bases, winning the first ever BBWAA Rookie of the Year Award.

In 10 big league seasons, Robinson hit .311, winning the NL Most Valuable Player Award in 1949. He led the Dodgers to six NL pennants and the 1955 World Series championship.

In the 1962 BBWAA election, Robinson was named on 77.5 percent of all ballots cast.

“Robinson could hit and bunt and steal and run. He had intimidating skills, and he burned with a dark fire,” wrote author Roger Kahn, who covered the Dodgers as a newspaper beat reporter in the early 1950s. “He wanted passionately to win… He bore the burden of a pioneer and the weight made him more strong.

“If one can be certain of anything in baseball, it is that we shall not look upon his like again.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related stories

Robinson’s Royal history

Jackie Robinson, circa 1946

Bob Feller pitches the first of 12 career one-hitters

17-year-old Bob Feller makes his first major league start

Robinson’s Royal history

Jackie Robinson, circa 1946

Bob Feller pitches the first of 12 career one-hitters