- Home

- Our Stories

- In 1971, Satchel Paige came to Cooperstown

In 1971, Satchel Paige came to Cooperstown

Leroy “Satchel” Paige had preached often about not looking back “because something might be gaining on you.”

But as the legendary pitcher, showman and civil rights activist approached the podium on the Library steps outside the Baseball Hall of Fame the morning of Aug. 9, 1971, he had no choice but to violate one of his most popular commandments.

For seven minutes, the Hall’s first Negro Leagues inductee would look back, with humor and poignancy, on a four-decade baseball odyssey that had seen him barnstorm to every nook and cranny of the United States – and beyond. That Paige had finally arrived at a destination he never thought would open its doors to him totally blew his mind.

The man who had struck out Jim Crow and laid the foundation for Jackie Robinson to integrate a sport and a nation soaked in the applause of the 2,500 mostly white spectators who had congregated in Cooperstown that historic day. But, while basking in the limelight, the tall, slender 65-year-old couldn’t help but feel conflicted. Voices dueled inside Paige’s head.

“Should he be grateful that the lords of hardball were finally acknowledging that blackball had brilliant players, or should he resent them – and all of America – for making him pitch his best ball in the shadows?” author Larry Tye explained in his award-winning biography, “Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend”.

“Was what counted that he was the first vintage Negro Leaguer to be voted into this most exclusive club and the (first) pitcher ever to make it with a losing record in the (white) Majors? Or was it that the Hall had tried to banish him to a separate and unequal wing?”

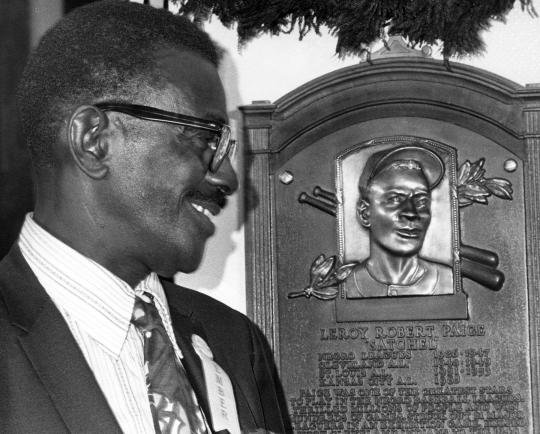

Though Paige had every right to be bitter, he opted to express gratitude rather than regret when he arrived at the podium and was shown the bronze plaque that would hang near ones immortalizing Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, Bob Feller, Dizzy Dean and Robinson.

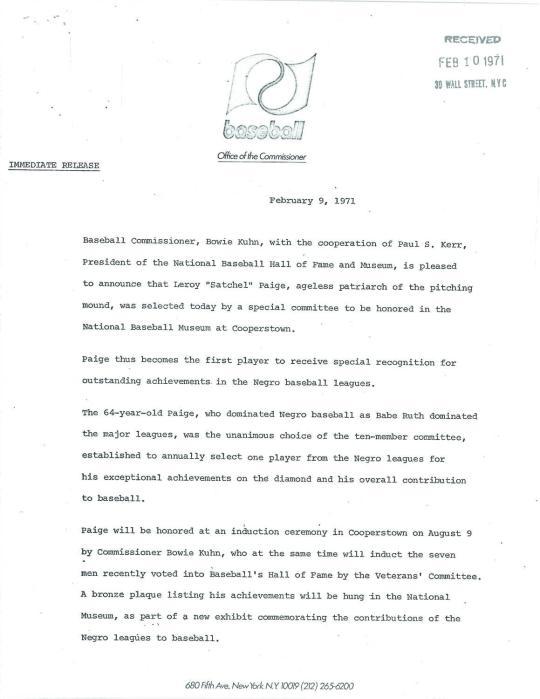

On Feb. 9, 1971, Paige had been nominated to the Hall of Fame, beginning a process that would end with his induction.

“Since I’ve been here, I’ve heard myself called some very nice names,’’ he began, grinning broadly beneath horn-rimmed glasses. “And I can remember when some of the men (enshrined in the Hall) called me some bad, bad names when I used to pitch against them.”

Paige evoked more laughter when he talked about how former Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck had been lambasted for signing him to a contract in 1948 at the advanced age of 42. “They told him to get anyone but Paige – he’s too old,’’’ Satchel said, pointing to his former boss in the crowd. “Well, Mr. Veeck, I got you off the hook today.”

Paige mentioned how he once pitched 165 straight days in a row, and jokingly explained why he took his sweet time walking to the mound. “I never rushed myself,’’ he deadpanned, “because I knew they couldn’t start the game until I got out there.”

His speech was interrupted by laughter 13 times, but it was much more than a comedic monologue. There were touching moments, too, like when he spoke candidly about how he wished he – not Robinson – had been the one to break baseball’s color barrier. But he added that, upon further reflection, he realized Jackie had been the right man for that enormous challenge.

Paige concluded by saying he “was the proudest man on the earth today,” prompting a standing ovation. Ted Page, a former teammate, was among those springing to their feet.

“I cried a little, but I came away from that ceremony a lot taller,’’ Page told the New Pittsburgh Courier, a newspaper with a predominantly Black readership. “When Satch stood up to be inducted, he was standing up for all of us who had played the game during the days when we knew we were good but weren’t recognized for being that way. His acceptance was vindication that we were as good as any man. I’m only happy that I was alive to see it.”

Paige’s unrivaled pitching and showmanship, particularly in interracial exhibition games against white aces like Dizzy Dean and Bob Feller, had paved the way for baseball integration. His induction into the Hall a half century ago would blaze trails, too. It opened the shrine’s doors for Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, and other Negro League legends whom history had forgotten. In the 10 years following Paige’s immortal moment, nine more of his Black contemporaries were enshrined. In 2006, a special committee righted a bunch more wrongs, electing 17 Black baseball pioneers, including the first female inductee, former Negro Leagues owner Effa Manley. In total, 34 Negro Leagues legends have followed Paige to Cooperstown.

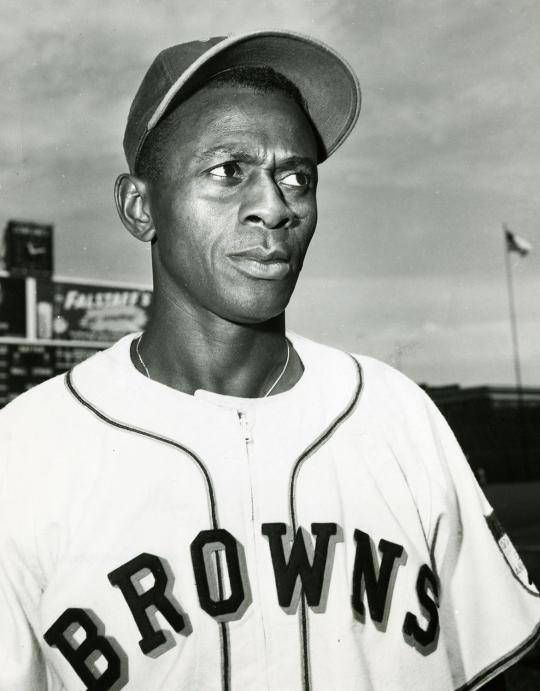

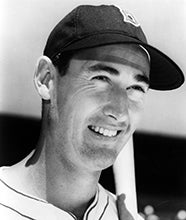

Satchel Paige pitched in six big league seasons, including the 1952 and 1953 campaigns when he was an All-Star with the St. Louis Browns. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Share this image:

Writers from African-American newspapers had long lobbied for Paige’s inclusion, but the campaign among the mainstream, white media didn’t really start until 1952 when Sport magazine’s Ed Fitzgerald publicly championed the cause. It would be another decade before the movement gained steam. According to Donald Spivey’s biography, “If You Were Only White”, a “Paige For Hall of Fame Committee” was formed in Connecticut in 1961, with founder John Henry Norton collecting letters of support.

Not surprisingly, Veeck became an ardent supporter, telling reporters: “If Paige had been brought up to the majors in his prime, today’s Cy Young Award would be known as the Satchel Paige Award.” Feller, who had waged mound duels with Paige in front of overflowing crowds, also jumped on board, calling Satchel’s exclusion from the Hall “patently unfair.”

The greatest impetus, though, would come from Ted Williams during his 1966 Hall of Fame induction speech. His unexpected comments pushing for the enshrinement of Paige, Gibson and other Negro Leaguers prompted organized baseball to take action. Two years later, a special 10-man committee was formed to recommend which Black pioneers should be inducted. That Paige would be the unanimous first choice was not surprising, given his crossover popularity and achievements. In addition to his barnstorming tours, he had helped Cleveland win a pennant and World Series title, and was the first African-American pitcher to start a game in the white big leagues and pitch in a Fall Classic. By tossing three scoreless innings in a 1965 game for the Kansas City Athletics at age 59, Paige made good on another one of his adages: “Age is a matter of mind over matter. If you don’t mind, it don’t matter.”

His pithy sayings and humorous names for his array of pitches (“Bat Dodger,” “Bee Ball,” “Hesitation Ball”) contributed to the larger-than-life persona he had created, but the slapstick occasionally muddied the argument that he was the greatest pitcher of all-time.

Though records are sketchy, the best information available suggests Paige had an overall Negro Leagues record of 146-64 with 1,620 strikeouts and just 316 bases on balls, and a American League record of 28-31, with a 3.29 earned run average and 33 saves. Paige argued those stats significantly short-changed him. He claimed he pitched in more than 2,500 games, winning roughly 2,000 of them, with 55 no-hitters and somewhere between 250-330 shutouts.

Numerous Hall of Famers vouched for his greatness. Dean said his fastball looked like a change-up compared “to that little pistol bullet Satchel shoots up to the plate.” Joe DiMaggio said Paige was the best and fastest pitcher he faced. Slugger Hack Wilson claimed Satchel made baseballs look as small as marbles to batters struggling to see and hit them.

The announcement of Paige’s unanimous election at a packed press conference in Manhattan on Feb. 9, 1971 was supposed to be a crowning moment for him and for baseball. But the festivities took a sour turn when it was revealed his plaque would hang in a different room than previous inductees. Though Paige publicly accepted this “separate but unequal” decision – “I’m proud to be wherever they put me” – the media did not.

“The notion of Jim Crow in Baseball’s Heaven is appalling,’’ columnist Jim Murray wrote in the Los Angeles Times. “What is this – 1840? Either let him in the front of the Hall – or move the damn thing to Mississippi.”

Jackie Robinson suggested Paige boycott the induction.

Privately, Satchel seethed, telling friends, “The only change is that baseball has turned Paige from a second-class citizen to a second-class immortal.”

On July 7 – Satch’s 65th birthday – saner heads prevailed and MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn and Hall President Paul Kerr announced Paige’s plaque would hang in the main hall. “I guess they finally found out I was really worthy,’’ Paige told reporters. “I appreciate it to the highest.”

Following his induction, he spoke frankly with reporters on a variety of topics, including his candidacy to become MLB’s first Black manager. “I could manage easy – I’ve been in baseball 40 years,’’ he said. “And I would want to manage.” But he also offered a reason why it wouldn’t happen. “I don’t think the white is ready to listen to the colored yet,’’ he said. “That’s why they’re afraid to get a Black manager. They’re afraid everybody won’t take orders from him. You know there are plenty of qualified guys around.”

Among them was Frank Robinson, who would topple that racial barrier four years later when he was hired to manage the Indians. Paige’s comments had set the wheels in motion.

It was all part of his remarkable, trailblazing journey – a journey that saw him bust open some doors in Cooperstown 50 summers ago, clearing a path for Black pioneers to finally feel at home in the home of baseball.

Scott Pitoniak is a freelance writer from Penfield, N.Y.

Related Stories

Satchel Paige, at 46, fires shutout

Satchel Paige pitches for A’s at age 59

Paige debuts with Indians at 42

Feller, Paige teamed up for 1946 barnstorming tour

Related Stories

Satchel Paige, at 46, fires shutout

Satchel Paige pitches for A’s at age 59

Paige debuts with Indians at 42