- Home

- Our Stories

- Humbled Kaat joins greatest team

Humbled Kaat joins greatest team

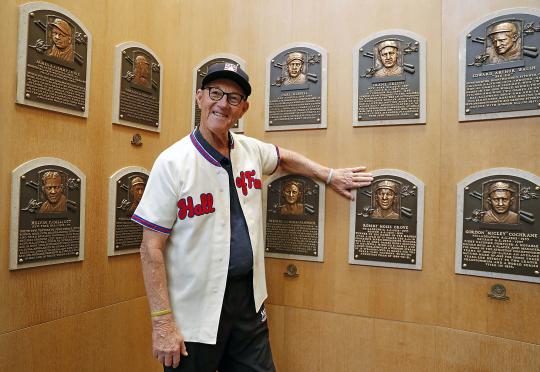

Jim Kaat, sitting in the Hall of Fame’s Plaque Gallery surrounded by the bronze images of his new teammates, had finally reached the sport’s pinnacle after eight decades in the game.

The emotions flowed easily.

“This is humbling,” is how Kaat described his feelings. “There are different levels of the Hall of Fame, and I would never be naive enough to put myself in a class with Sandy (Koufax) and Gibby (Bob Gibson) and Seaver and Marichal, but I’m honored to be here as a representative of longevity and maybe dependability, accountability. I’m happy about that.”

Be A Part of Something Greater

There are a few ways our supporters stay involved, from membership and mission support to golf and donor experiences. The greatest moments in baseball history can’t be preserved without your help. Join us today.

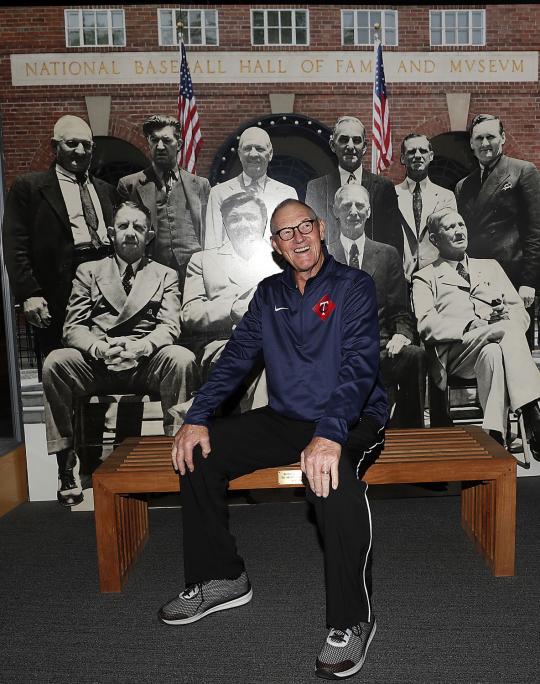

Kaat, along with his wife Margie, were at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum on May 10, taking part in an Orientation Visit afforded all recent electees in order to prepare for the upcoming Induction Ceremony.

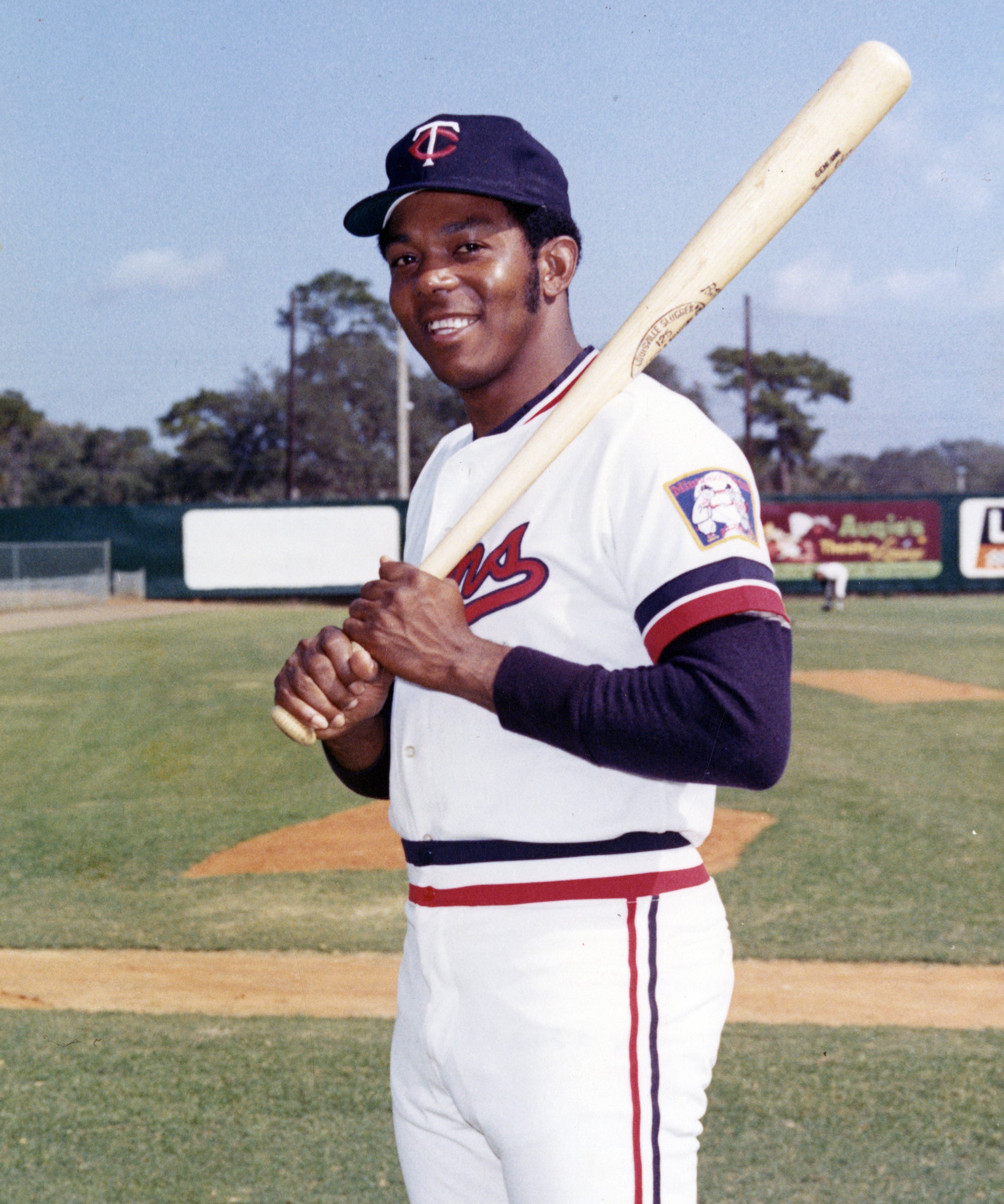

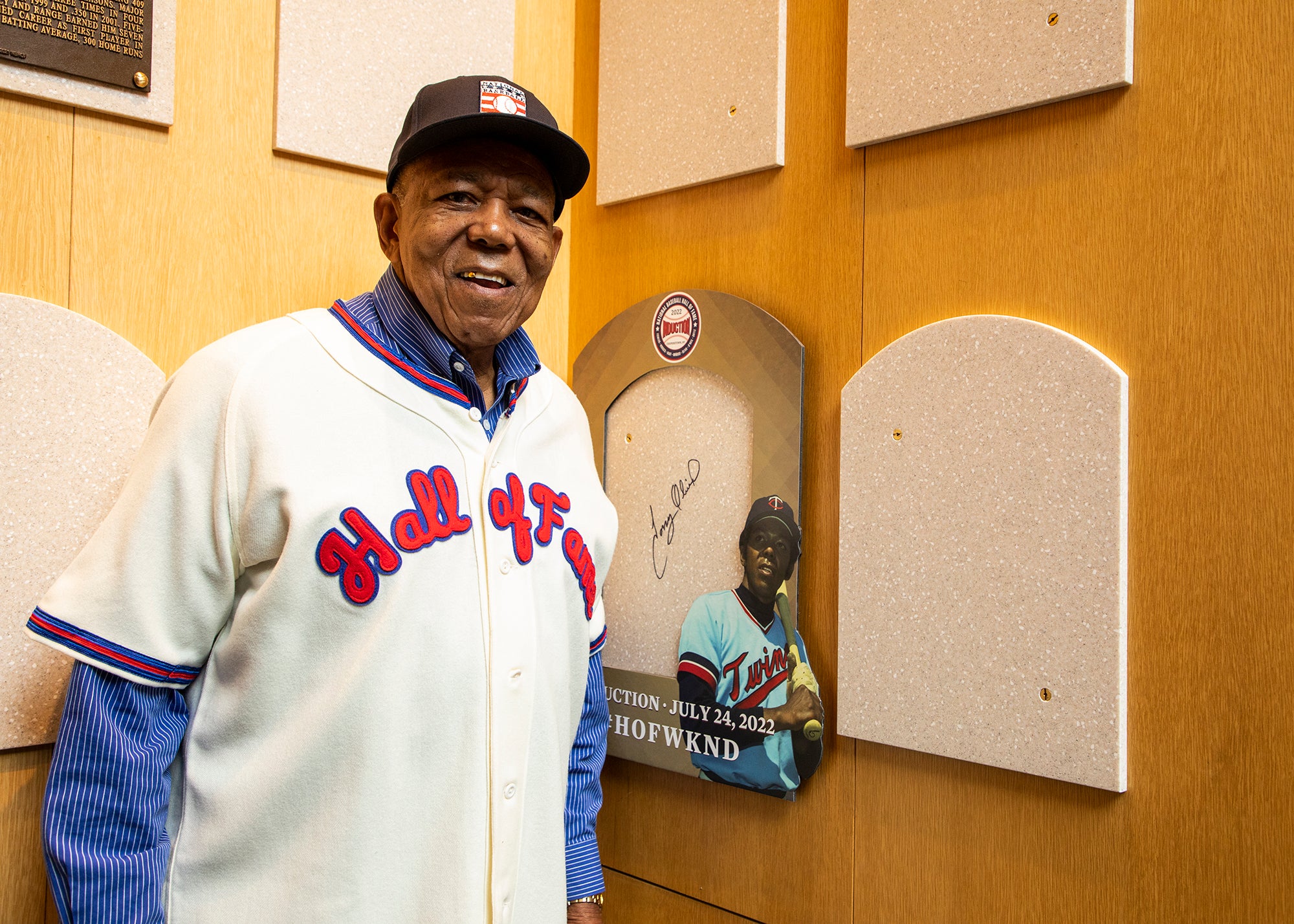

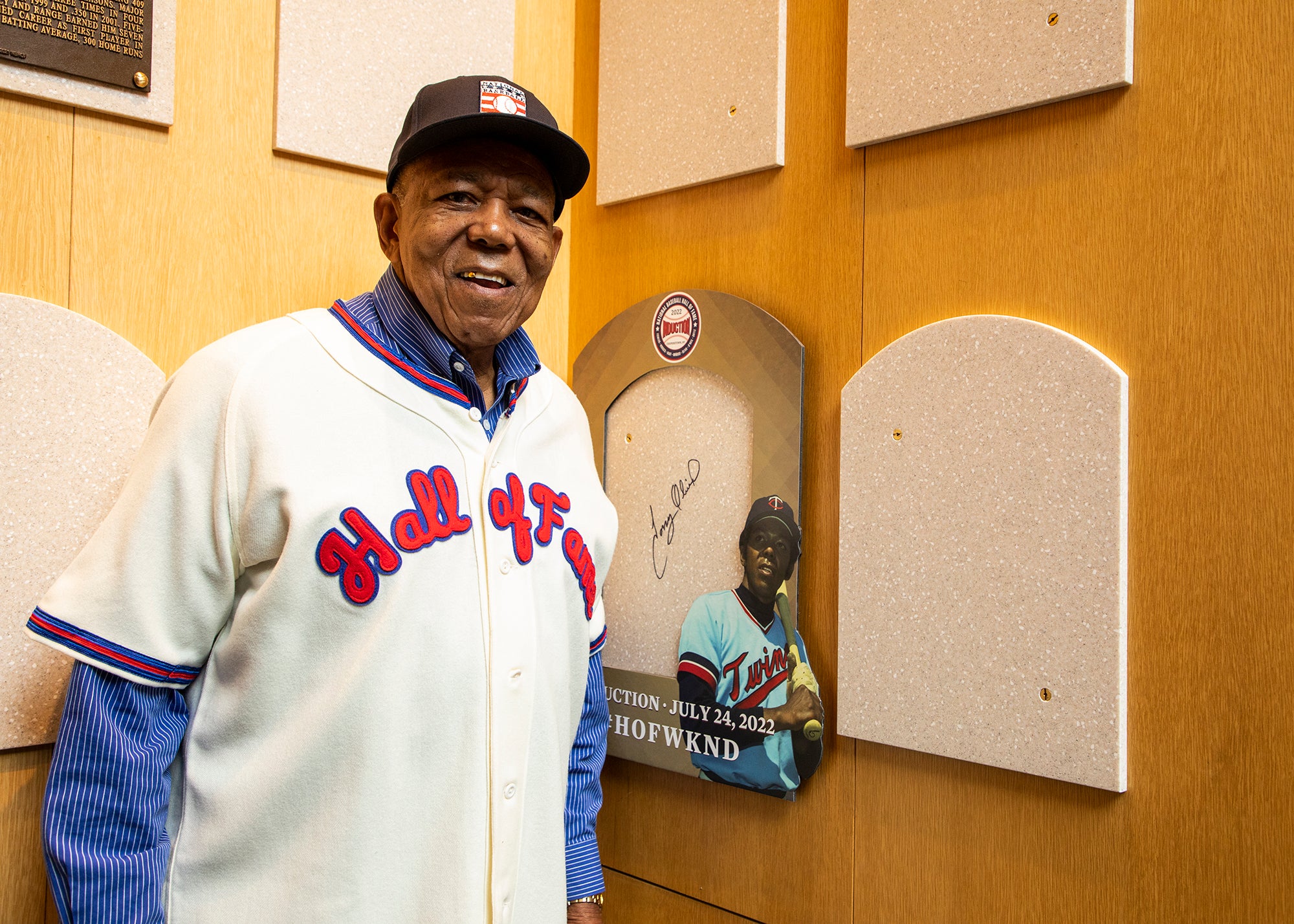

The Hall of Fame Class of 2022 member was elected via the Golden Days Era Committee, along with former Minnesota Twins teammate Tony Oliva, Gil Hodges and Minnie Miñoso, on Dec. 5. The entire seven-member class also includes Early Baseball Era Committee electees Bud Fowler and Buck O’Neil, as well as Baseball Writers’ Association of America electee David Ortiz.

The Class of 2022 will be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame at 1:30 p.m. ET on Sunday, July 24 on the grounds of the Clark Sports Center in Cooperstown.

“When I got the call from Jane (Hall of Fame Chairman Jane Forbes Clark), as soon as you hear those words, ‘This is Jane Clark’ … I know they don’t call with bad news,” Kaat said with a laugh. “And then Tony La Russa called and said, ‘You know your life changes forever.’ And I think the deeper I get into the process, the more humbling it is because I recognize how we didn’t earn anything through the ability to play baseball, we were gifted. It is a gift. I’m glad I was able to make the most of that.”

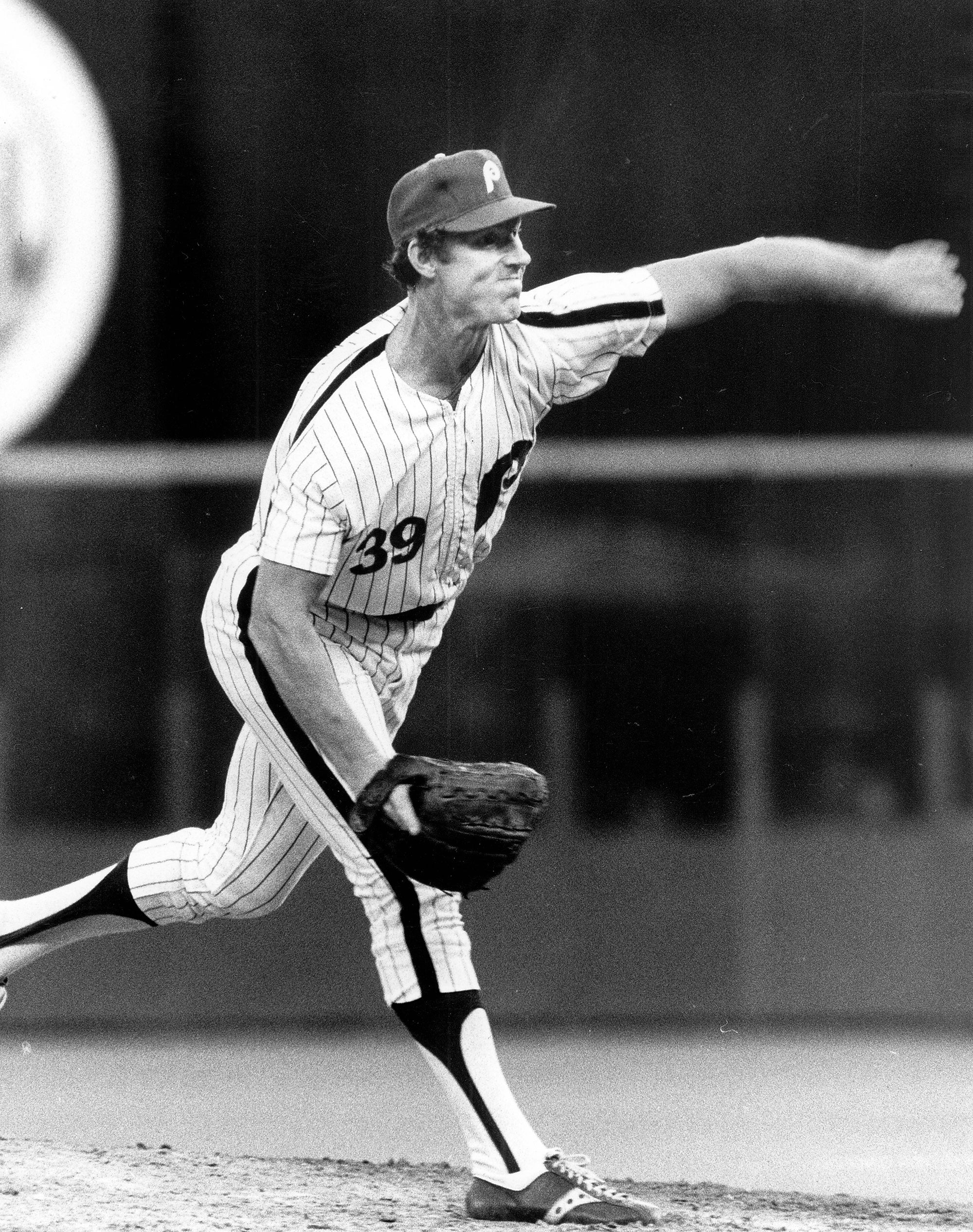

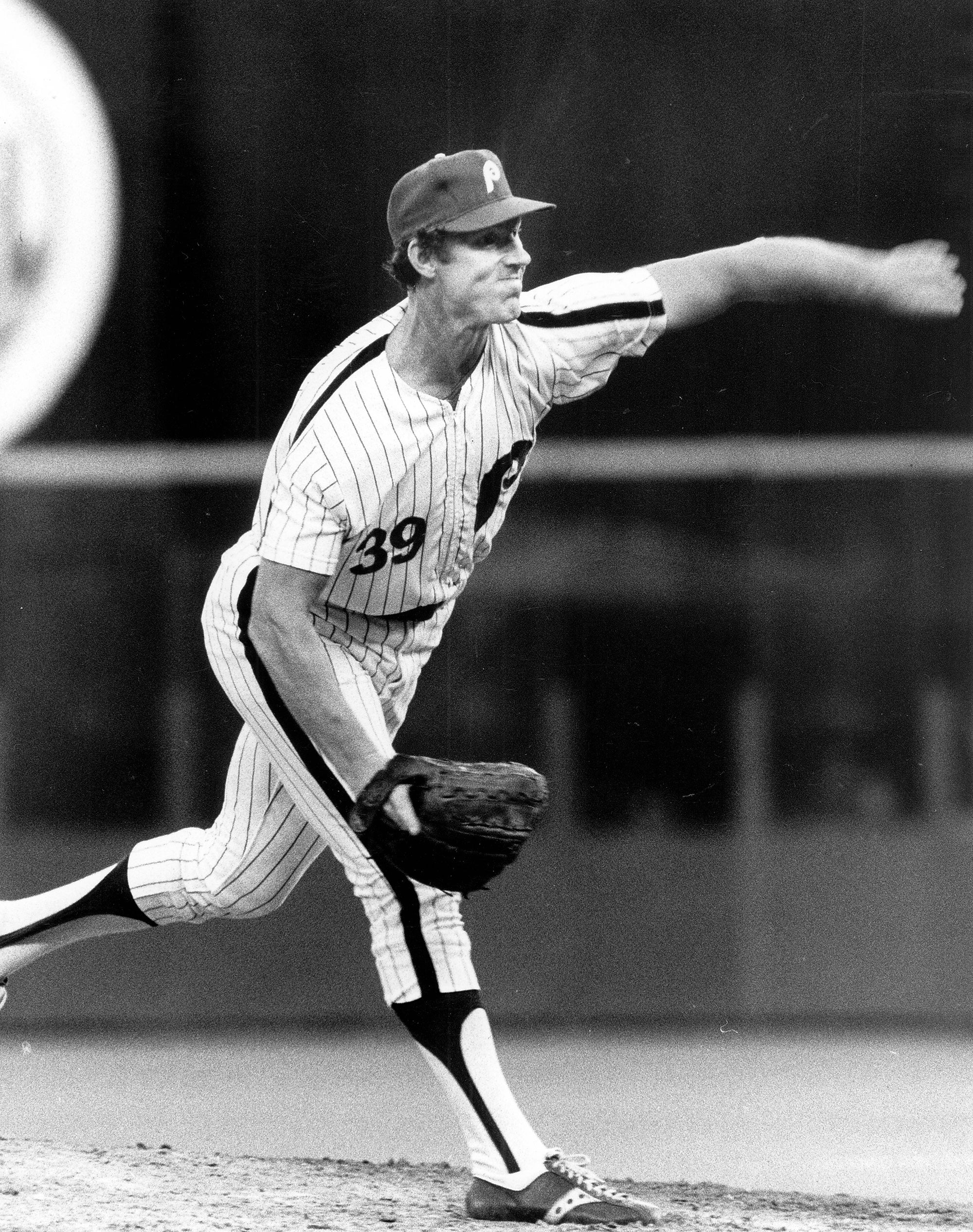

Kaat, 83, who made his big league debut at the age of 20 and tossed his last pitch at 44, was a 6-foot-4 southpaw who towered on a major league mound for 25 seasons with the Senators, Twins, White Sox, Phillies, Yankees and Cardinals, winning 283 games. A three-time 20-game winner, three-time All-Star and 16-time Gold Glove Award winner, Kaat’s 625 career games started ranks 17th all-time and his 4,530.1 innings pitched rank 25th. His 16 Gold Glove Awards is tied with Brooks Robinson for second most all-time, behind fellow pitcher Greg Maddux (18).

The Twins recently announced the franchise will formally retire Kaat’s uniform No. 36 on July 16. He is the club’s all-time leader in wins (189), games started (422) and innings pitched (2,959 1/3).

Kaat, as a stalwart starting pitcher, not only helped the Twins win the 1965 American League pennant and 1969-70 AL West titles – and the Phillies win National League East titles from 1976-78 – but late in his career transitioned to a key relief ace and was a key member of manager Whitey Herzog’s bullpen crew as the Cardinals captured the 1982 World Series.

His career has also included a 1984-85 stint as a coach with the Reds, a Twins broadcaster from 1988-93, a Yankees broadcaster from 1995 to 2006, and an MLB Network broadcaster from 2009 to the present.

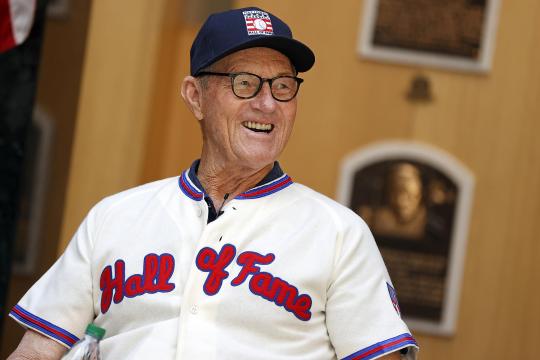

After a two-hour tour of the Museum, where he received a crash course of the game’s history dating back to the 19th century up through the present, Kaat ended the morning in the Plaque Gallery. It was there that he donned a Hall of Fame jersey and cap, signed the backer at the spot his plaque will arrive this summer, and took questions from a media contingent.

“We welcome Jim to the Museum, to the Hall of Fame, to Cooperstown, and to probably the best team he’s ever been on,” said Clark in introducing Kaat to the crowd.

“No question,” Kaat responded.

Asked how to describe his day, Kaat referred to its start watching the Generations of the Game film in the Museum’s Grandstand Theater.

“I think that every organization should have every player in their organization see that video. And when I saw that video, my first thought was, ‘I don’t belong.’ I mean, there’s so many great players there, but I’m truly humbled,” Kaat said. “As I’ve told Jane and many people, my dad drove here in 1947 to see Lefty Grove inducted. So I have known about the Hall of Fame and visited here many, many times. I know how special it is to be honored, particularly in my case, by players you played against, played with, executives who saw you play.”

Kaat would later make a point of posing next to Grove’s plaque before he left the Gallery.

With Kaat’s induction speech complete – except for some possible minor tweaking – he admitted without giving too much away that the role his father played in his life will be a major component.

“Sandy Koufax, in his words to me, said, ‘Make your speech short. I have so many people to thank, but I respect the fact that there are several speakers that day and you need to be respectful of everybody’s time,” Kaat said. “The person that will get the most time from me will be my dad. He was such a baseball fan. June 26, 1946, is when I fell in love with baseball. He took me to a doubleheader, Red Sox-Tigers. I saw Ted Williams, Bobby Doerr, Hank Greenberg, Hal Newhouser, all future Hall of Famers.

“When I walked up the ramp to find our seats in that dark green cathedral called Briggs Stadium I saw the greenest green, the uniforms were the whitest white. I think my little seven-year-old brain said I want to be one of those guys.”

Kaat would later explain it was his father that helped him stay away from the travails of being a “bonus baby.”

“In 1957, if you got more than $4,000 to sign, you’d have to occupy a seat on the major league roster for two years. The only two that I can think that overcame that were Sandy Koufax and Harmon Killebrew. My dad followed that because he read the Sporting News every week,” Kaat said. “So Dick Wiencek, the Washington scout, offered me $4,000. In the meantime a scout from Chicago called and said he thought he could get his son $25,000. That meant I’d go and sit on the bench for two years. And so my dad said, ‘Thanks, but Jim’s gonna take the $4,000 and go to the minor leagues and learn to play the game right.’”

In the collection of the Hall of Fame is an April 1957 Washington Senators scouting report on the 18-year-old Kaat, raised in Zeeland, Mich., while he was attending nearby Hope College in Holland, Mich.

The scout, Dick Wiencek, in his comments, wrote, “This boy can really fire. He throws bullets. A topnotch prospect.”

Wiencek would ultimately sign 72 players – including Kaat and fellow Hall of Famer Bert Blyleven – the most in baseball history.

A witness to a number of Hall of Fame Induction Ceremonies over the years, dating back to 1966 when the Twins faced the Cardinals in the Hall of Fame Game at Doubleday Field, he also saw longtime Twins teammate Harmon Killebrew’s 1984 induction, and the 2018 induction the year his longtime broadcast partner Bob Costas was honored with the Ford C. Frick Award, among others.

Admitting with a chuckle that he’s probably signed his name 3,000 times since he was elected, Kaat talked about how the news affected others.

“I guess an example of that would be, I think it was two days after I got ‘the call’ I see a number on my phone. I don’t recognize it. The voice said, ‘Is this Jim?’ And I said, ‘Yes. Who’s this?’ It was Al Kober, someone I toured the Hall of Fame with in 1956. He was my roommate at Hope College. He was right-handed pitcher and I was a left-handed pitcher. Our schedule was 12 games – six doubleheaders – he pitched six and I pitched six. He said that he had just reserved three rooms in Utica (45 miles from Cooperstown). And I don’t think we’ve seen each other in 40 years. And he’s got his family coming. So I think it’s moments like that, that you realize how special this is.”

It can be said that the hallmark of Kaat’s career was his longevity, a trait that he learned early on would have to be accounted for every spring.

“I had coaches early on like Eddie Lopat, who was very successful for the Yankees. His best fastball couldn’t black your eye from 60 feet, but he knew how to pitch and he taught me the art of pitching,” Kaat explained. “So I think that being able to adjust every year. As Eddie told me after my first really kind of coming out year in ‘62, he said, ‘Now you know you’re gonna have to be twice as good next year to be as good as you were this year.’ So I’m scratching my head like what does that mean?

“What it really told me is you don’t just sit back and say, ‘Well, I’m here. I’m gonna stay here.’ You have to keep on trying to improve. I think that’s what drove me every year to go to spring training like I got to earn my spot and then you kind of adjust with the times.”

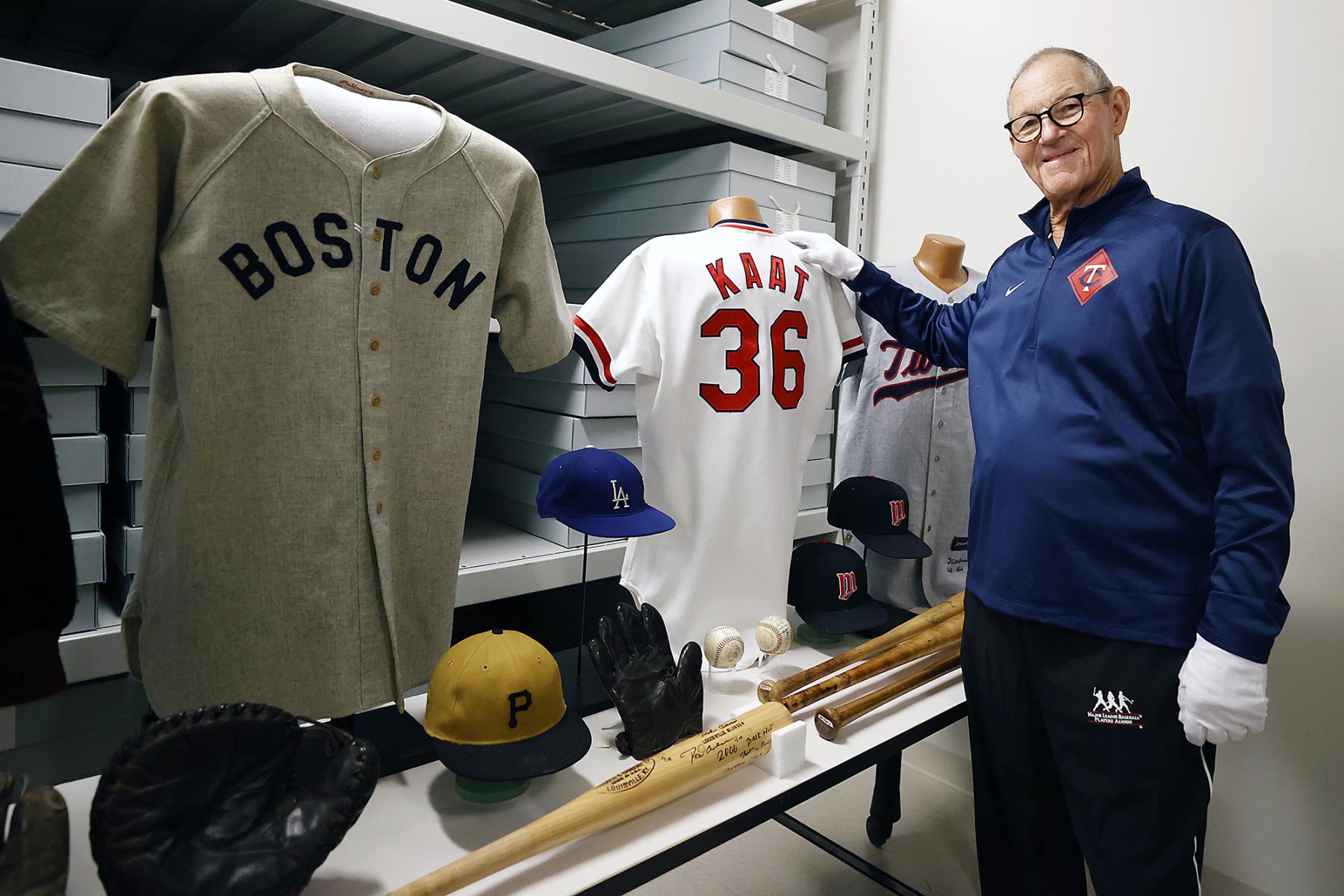

Kaat’s tour through the Museum not only included reconnecting with a 1983 Cardinals home uniform jersey he donated, marking his 25th consecutive year of pitching in the majors, but also checking out a seamless baseball from the 19th century (“Probably why they started using slippery elm.”), looking at a picture of Ty Cobb sliding spikes high (“I remember seeing that as a kid”), remembering having coffee with Joe Medwick in Spring Training, and marveling at Ted Williams at the plate (“I looked at that stance a few times from the mound.”)

While in Collections, the longtime pitcher swung a bat once used by Babe Ruth, the one Ted Williams hit his 521st and final round-tripper, and the club Killebrew used to club his 500th homer.

“The magnitude of the attention by being a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame,” Kaat reflected toward the end of the day, “is so much different than being, ‘Oh, he had a nice career. He played for 25 years.’”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Kaat's career lengthened with transition to bullpen

Oliva’s Orientation Visit brings back memories from a lifetime in baseball

Ortiz overwhelmed by visit to Hall of Fame

Walker gets history lesson in visit to Hall of Fame

Kaat's career lengthened with transition to bullpen

Oliva’s Orientation Visit brings back memories from a lifetime in baseball