- Home

- Our Stories

- Hitters continue to chase .400

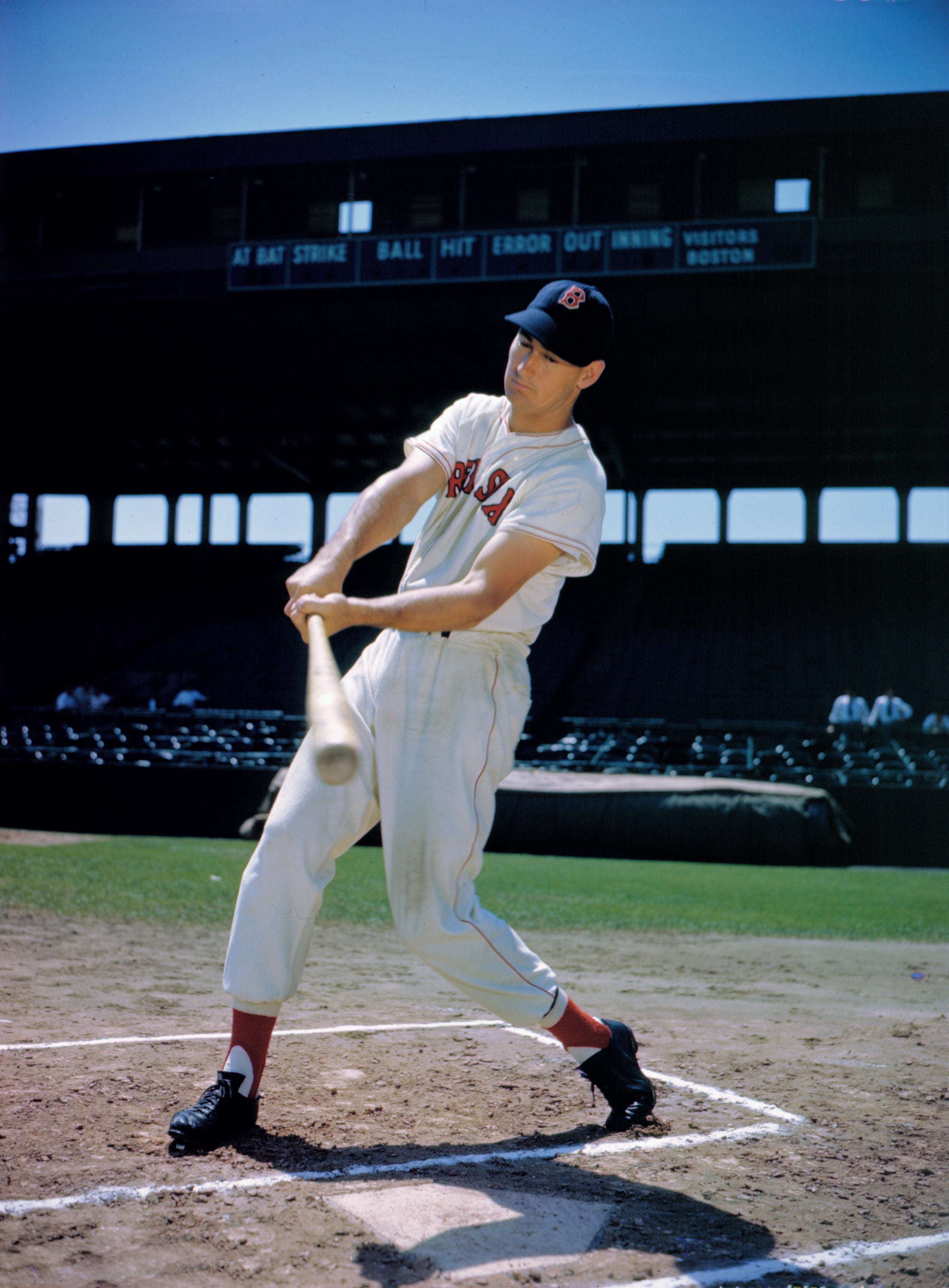

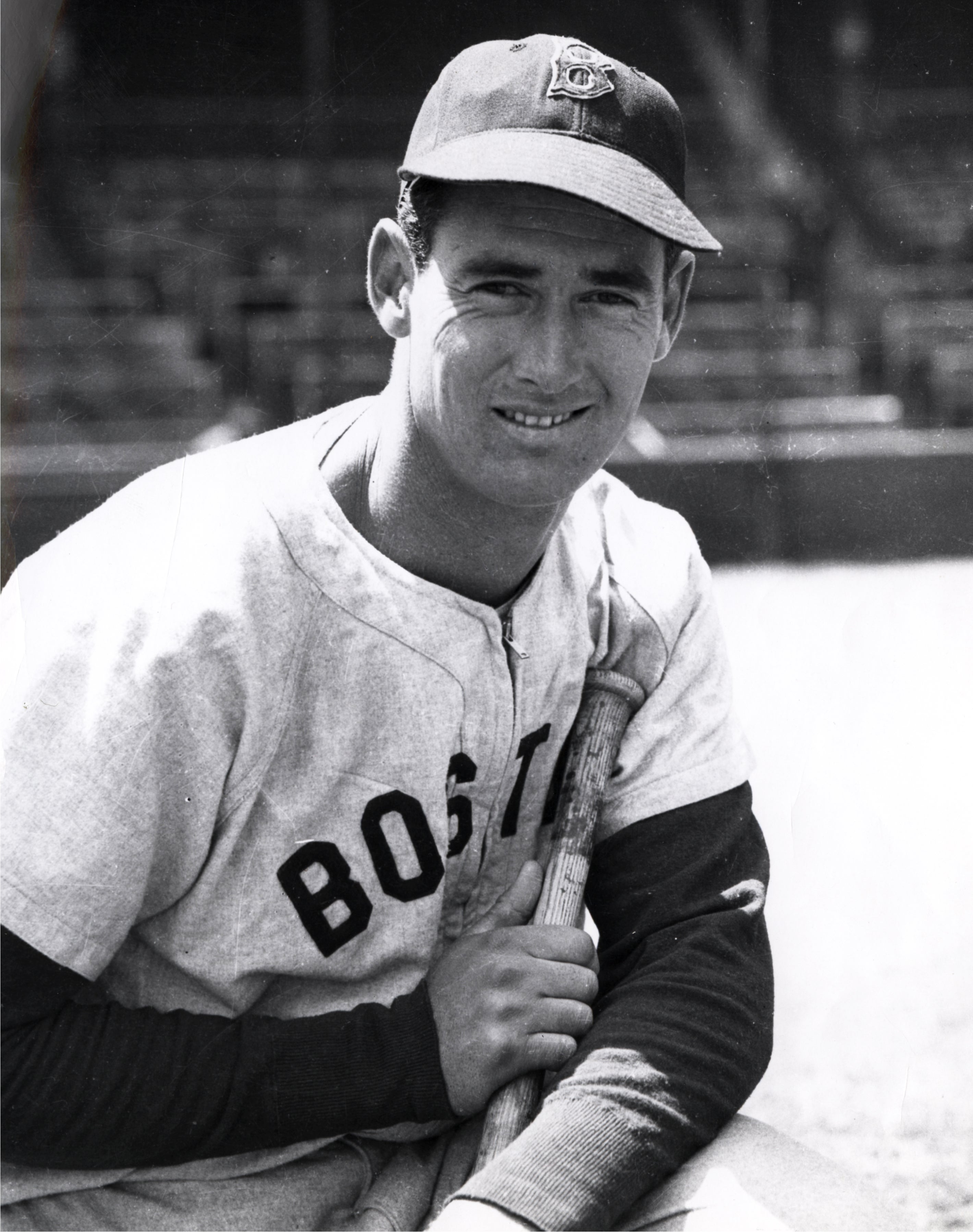

Hitters continue to chase .400

Impressive as it was, the number – at the time – seemed something less than an enduring standard.

But today, any player that comes within 30 points of Ted Williams' magic .406 – even as early as June – becomes an instant celebrity.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

It's a testament to the power of numbers in baseball – and to a batting average that has not been equaled since.

"I think it can be done – and I think I would have done it if we had completed the strike-shortened season," said Hall of Famer Tony Gwynn, who was hitting .394 – the highest final average since Williams in 1941 – when the strike ended the 1994 campaign. "When Ted and I talked about (hitting .400), we figured you needed between 240 and 260 hits. That's what it's going to take, unless you can walk 180 times."

Gwynn never approached those walk totals. Williams, meanwhile, is one of only four players who ever drew more than 160 walks in a season. But in 1941, it was all about swinging the bat for the man known as Teddy Ballgame.

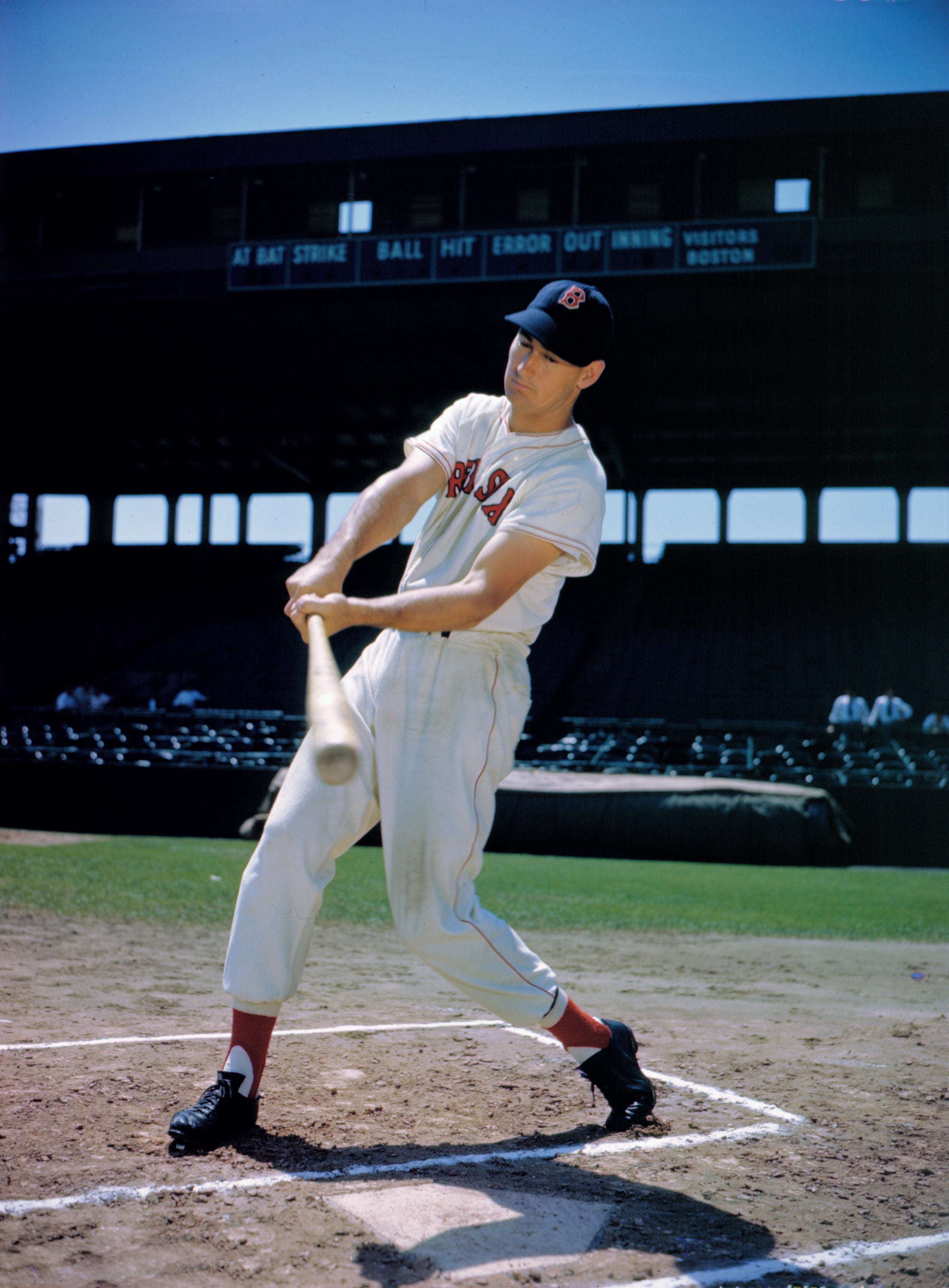

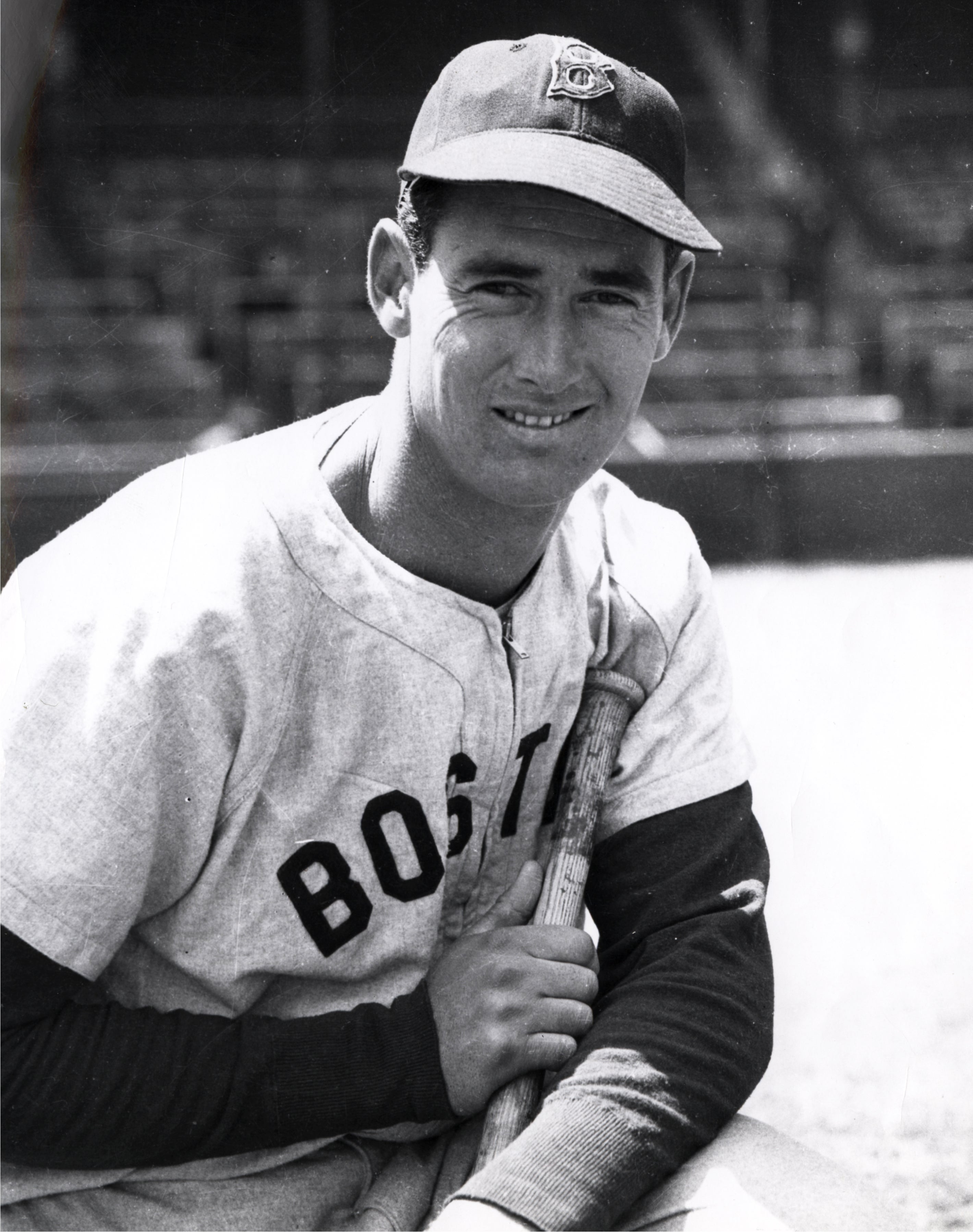

In just his third big league season, the Red Sox's left fielder had already developed a reputation as one of the game's best pure hitters. He led the major leagues in RBI as a rookie in 1939 and in runs scored in 1940, then began the 1941 season on a 6-for-11 tear that saw him standing at .429 at the end of May. In June he had his worst month of the season – hitting just .372 – but he hit .429 in July and .402 in August to leave him with a .407 batting average as September dawned.

The Yankees, who bolted out to the American League lead over the summer on the strength of Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hitting streak, had the pennant all but wrapped up en route to a 17-game final cushion over the Red Sox. But the season dripped with drama as Williams chased .400.

Heading into the last days of the season, Williams stood at .3995 – which would be rounded up to .400 – with two games yet to be played against the Athletics in Philadelphia. Tales have lived for decades that Red Sox manager Joe Cronin – himself a future Hall of Famer – suggested to Williams that he could it out the final games to reach the mark.

"I'll play," Williams told Cronin. "Hitting .3995 ain't hitting .400. If I'm going to be a .400 hitter, I want more than my toenails on the line."

Cronin later denied offering Williams the chance to sit out, saying: "We had an agreement made a week before that Ted would play every game no matter what happened. I never offered to let him sit any games out to protect his average."

But whatever the circumstances, the results were the same. Williams and the Red Sox were scheduled to play a season-ending doubleheader against the A's on Sept. 28. As Williams stepped in for his first plate appearance against Philadelphia's Dick Fowler, A's catcher Frankie Hayes relayed to the Splendid Splinter what Hall of Fame manager Connie Mack had told his team:

"Mr. Mack told us he'd run us all out of baseball if we let up on you,” Hayes said. “You're going to have to earn it."

Williams began his day with a single to right. His next at-bat produced a home run. Porter Vaughan faced Williams in his third at-bat and surrendered another single. Another single followed against Vaughan in the seventh inning before Williams reached on an error in his last at-bat. His 4-for-5 day left him standing at .4039.

Amazingly, Williams appeared in the starting lineup for Game 2 – despite the fact that an 0-for-5 would have left him right back at .3995. But his 2-for-3 performance put him at .4057 – and forever in the country's sporting conscience. The 23-year-old slugger was well on his way to his goal: Becoming the greatest hitter who ever lived.

The press celebrated Williams' achievement, but it was not considered a once-in-a-lifetime moment – for good reason. Just 11 years earlier, Bill Terry of the Giants hit .401 – the eighth different season of .400-or-better in the 11-season span between 1920 and 1930. Williams' .400 mark was the 13th of the modern era – beginning in 1901 – meaning that on average a .400 hitter appeared in about one out of every three seasons.

But following World War II, .400 hitters became extinct. In the seasons since Williams' jewel, just four players have qualified for their league's batting title with better than a .380 average.

The first was Williams himself, who hit .388 in 1957 at the age of 38. After hitting .343 before the All-Star break, Williams hit an incredible .453 in the second half with 78 hits in just 60 games. In his final 12 games of the season, Williams hit .632 – enough to close in on .390 but without enough time to approach .400. His average climbed as high as .393 on Aug. 17, but he never reached the .400 mark after June 5.

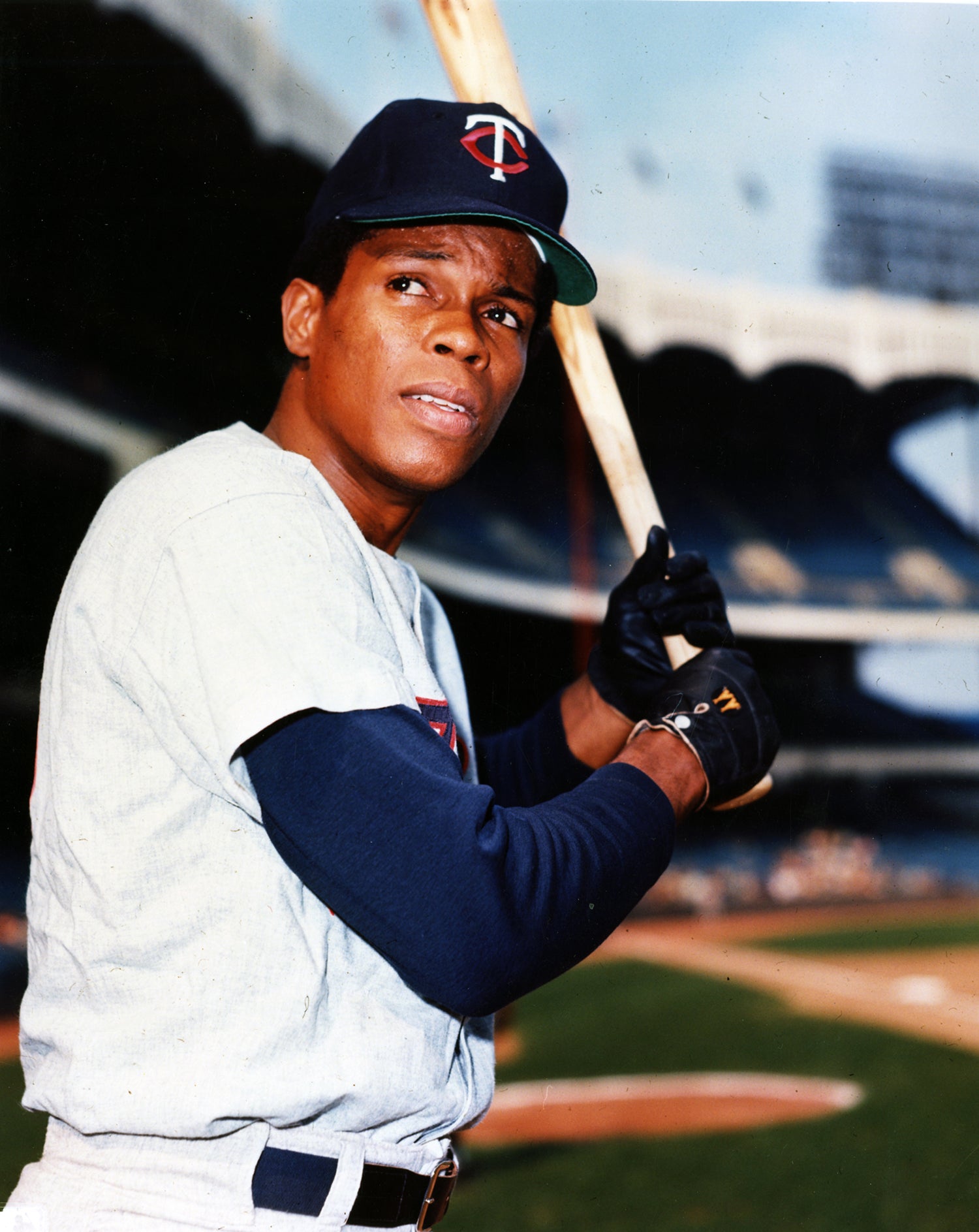

The next challenge came from Rod Carew, who virtually owned the American League batting crown throughout the 1970s en route to the Hall of Fame. Entering the 1977 season, the Twins' first baseman had won five AL batting titles and missed out on a sixth in 1976 by .002 points. But in 1977, Carew left no doubt about the title – hitting .388 en route to the American League Most Valuable Player Award.

Carew's run at .400 began early in the season. By July, he had pushed his average to .411 and found himself on the cover of Time Magazine in July as the nation became captivated with his hitting skills. But Carew dropped below .400 by July 11 and down below .380 by the end of August, with a late-season push returning him to .388.

"He has the best chance," said legendary hitting instructor Charley Lau of Carew's quest for .400. "That's if anybody can do it."

Three years later, the Royals' George Brett – a Lau disciple – came even closer. Brett, who edged out Carew for his first batting title in 1976, was hitting .337 on June 10 a right ankle injury sidelined him for a month. When he returned, a torrid month of July left him at .390 (he hit .494 in July), and he kept up the pace until he topped the .400 mark on Aug. 17. He peaked at .407 with a 5-for-5 performance on Aug. 26 and stood at .400 after the games of Sept. 19 – the latest anyone has been at .400 since Williams in 1941.

"I sure hope he does it," Williams said at the time. "Because I'm sick of people calling me every time someone gets close."

But in his final 13 games of the season, Brett was a mortal 14-for-46 (.304), knocking him down to .390. It was the greatest season of his Hall of Fame career.

In 1994, a third future Hall of Famer – Gwynn – made his run at Williams.

The Padres' right fielder was a four-time National League batting champion heading into the 1994 campaign, but hadn't won a crown in four seasons. But that year, Gwynn kept his average in the high .380/low .390 range throughout June and July. He appeared ready to make a run at .400 before the strike stopped the season Aug. 12 with Gwynn at .394. However, Gwynn wasn't above .400 after May 15.

"The media attention now might make it impossible to do," Brett said. "But despite the media that was there for me, I really thought I was going to do it. If you get close, you're not going to back down."

Since 1994, only one player – Hall of Famer Larry Walker in 1999, who hit .379 – has topped the .375 mark. But the quest for .400 continues. Meanwhile, Williams has ascended into the pantheon of great hitters.

It was his destiny after that monumental weekend in Philadelphia.

"All I want out of life," Williams famously said, "is that when I walk down the street folks will say, 'There goes the greatest hitter who ever lived.'"

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

Ted Williams goes 6-for-8 in doubleheader to finish season at .406

The Royals’ George Brett goes 4-for-4 to raise his average to .401

Ted Williams draws 2,000th career walk

Ted Williams goes 6-for-8 in doubleheader to finish season at .406

The Royals’ George Brett goes 4-for-4 to raise his average to .401