- Home

- Our Stories

- Harry M. Stevens created the modern ballpark experience

Harry M. Stevens created the modern ballpark experience

Harry M. Stevens was called during his lifetime the “world’s greatest sporting caterer,” “the man who parlayed a bag of peanuts into a million dollars” and “a true pioneer in the field of gastronomy.”

Despite his hardscrabble start in America at the dawn of the 20th century, this British-born former steel mill worker became a true American success story as a renowned purveyor of hot dogs, pop and cigars to the sports world – forever changing the way fans experience the game.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

When Stevens passed away in 1934 at the age of 78, the concessionaire, whose fame approached that of the players in the ballparks and arenas that he stocked with refreshments, was remembered in newspapers across the country.

“In his passing, one of the great personalities of the game fades out,” wrote Spink Award-winner Grantland Rice. “Harry Stevens was something more than the man who gave fame to the hot dog, the sandwich and the peanut. Administering to the needs or desires of many millions, he held the affection and the admiration of all who knew him.

“Above all, he had the striking type of personality that caught instant attention – the vital human spark that so few ever hold. He had brains and character and courage, and the green mound can shelter little more.”

Born in London, the son of a lawyer, Stevens came to the United States with his young family in 1882. After living in New York City for a short while, they soon settled in Niles, Ohio, where his wife had friends. Employment as an iron puddler, in highway construction and as a door-to-door bookseller followed, but it was when he attended a minor league baseball game and saw the need for a new-and-improved scorecard that his fortunes began to change.

“After the book game I hit upon the idea of selling scorecards in the Tri-State League. Gee, but I was some barker. It makes me laugh to look back upon those days,” Stevens recalled in a 1915 interview. “I went through the stands shouting at the top of my voice. I can make myself heard now, but in those days – well, can you imagine?

“But my real hit was made in the world’s series between St. Louis and Detroit (1887). I took up the scorecard game in that series at the request of good old Chris von der Ahe (St. Louis owner). Year after year I added to my circuit.”

After adding such big league venues as Pittsburgh and Washington, a chance meeting with New York Giants shortstop and future Hall of Famer John Montgomery Ward led Stevens to expand his scorecard business to the Polo Grounds in 1894. Later that year, he got the concession contract for Madison Square Garden, where his first jobs included a six-day bicycle race and the Westminster Kennel Club show.

This was a turning point for Stevens’ business, as his concessions soon dotted the sporting landscape at contests involving baseball, football, wrestling, boxing, polo matches and horse racing, to name a few. And the caterer, with his ever-expanding livelihood based most often on collecting nickels and dimes, would soon develop his own philosophy when it came to feeding sports fans.

“The races at the various tracks are called early in the afternoon,” Stevens said. “The patrons usually go out an hour or so before the first race is called to look over the track and make their bets, and usually count on getting their lunch on the scene. That means they want something substantial in the way of a meal.

“The baseball games begin in the middle of the afternoon as a general rule, and that means the spectator has had his lunch,” he added. “The crisp air sharpens his appetite and he wants something to eat to satisfy this craving before he goes home to dinner. He has no time to leave his seat between innings, so he wants something he can eat while watching the game. Baseball crowds are great consumers of hot dogs, peanuts and bottled drinks, while heavier food is popular at racetracks.

“Prizefight crowds go in for mineral waters, near-beer and hot dogs. A boxing crowd also is a great cigar consuming crowd,” he continued. “Chocolate goes well in spring and fall, but the hot dog is the all-year-round best seller.”

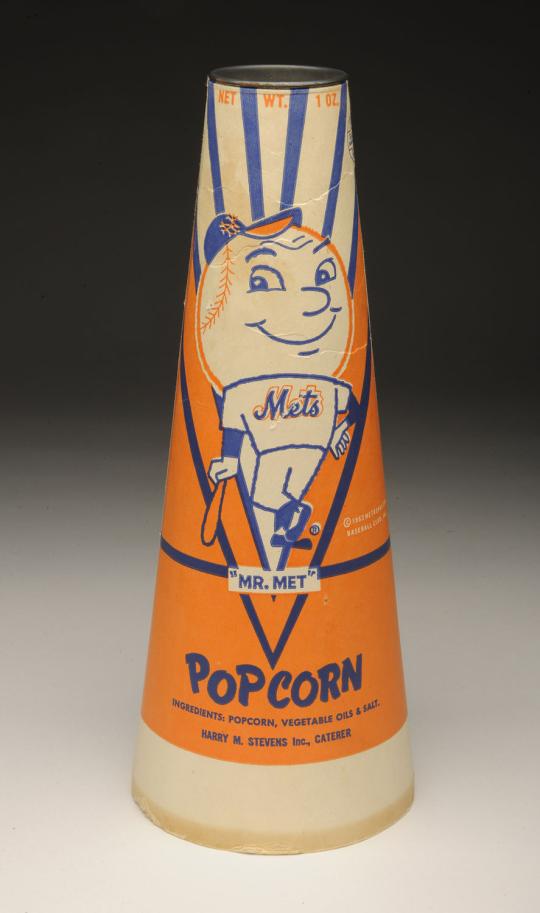

Having originated the modern scorecard, Stevens also lays claim to introducing his so-called “double-jointed peanuts” to fans, growing them in Virginia and shipping by the carload. He is also sometimes given credit for inventing the great American hot dog (a claim most historians disagree with). The story goes that on a cold spring day in 1901, a Polo Grounds crowd turned their noses up at the usually fare until Stevens had his workers place warm sausages, with mustard and relish, inside warm rolls. Originally called “dachshund sandwiches,” a sports cartoonist with trouble spelling instead dubbed them “hot dogs.”

“Ham and cheese sandwiches had things to themselves for the first 15 years of my time at the ballparks,” said Stevens in a 1931 interview. “If I were poetic I would say that one touch of the frankfurter made the whole world kin. At the counters in the rear of the Polo Grounds, you would find a prominent banker eating a frankfurter and drinking a glass of beer, and beside him would be a truck driver doing precisely the same thing. Both had hurried out to the game, and this was their lunch.

“The excitement and the fresh air of the ballgame appear to sharpen the appetites even of dyspeptics. When the desire for refreshment meets up with a tempting-looking frankfurter it is good-bye for the latter.”

Soon, Stevens’ business letterhead described him as publisher and caterer – “From the Hudson to the Rio Grande,” referring to his work at the Polo Grounds and a racetrack in Juarez, Mexico. Over the years, he also obtained concessions at, among many other locations, Yankee Stadium, Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field, and Braves Field and Fenway Park in Boston. It was said of his staff that it catered to as many as 250,000 persons at various ballparks and racetracks on a summer afternoon.

An eyewitness to thousands of sporting events, Stevens’ vast affection toward the game of baseball remained throughout his adult life. He often said his greatest thrill came when his son, Joe, playing for the Yale baseball team at the Polo Grounds, came up in ninth inning and knocked in the winning run that defeated Princeton.

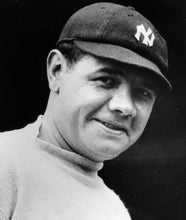

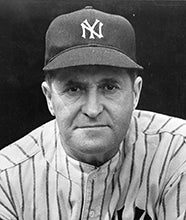

After Stevens’ death in New York City, his funeral service was attended by more than 500 people from the world of sports, including from baseball Babe Ruth, Yankees manager Joe McCarthy, National League President John Heydler, New York Giants President Charles Stoneham, Brooklyn Dodgers President Stephen McKeever, Boston Braves President Emil Fuchs, the widows of John McGraw and Christy Mathewson, and big league umpires Red Ormsby, George Hildebrand and Lou Kolls.

In 1994, Aramark, the food-service provider, acquired Harry M. Stevens Inc., founded in 1887, which still operated food and drink concessions at some of the nation’s biggest ballparks and arenas.

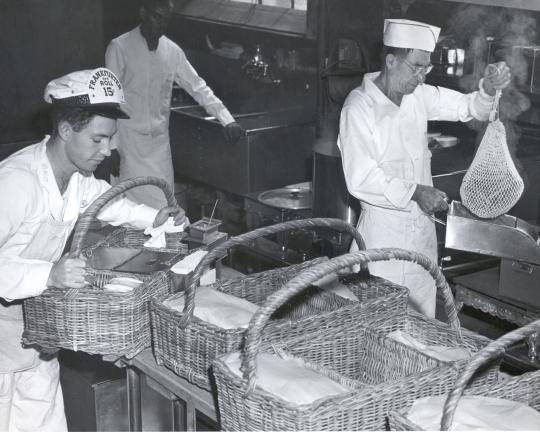

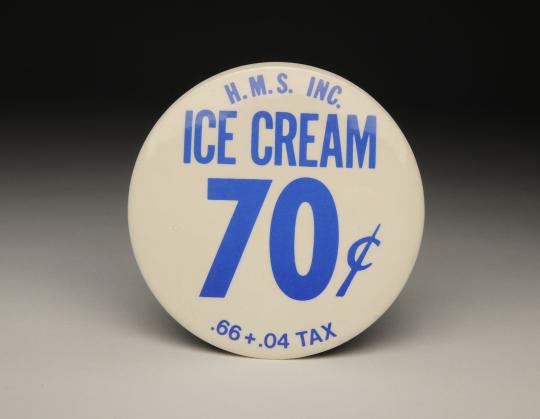

The Hall of Fame's collection contains many scorecards and concessions from Harry M. Stevens, Inc., documenting his impact on the ballpark experience.

Late in his life, Stevens, the highly successful businessman, Shakespearean scholar, friend of those in politics, finance, art, literature and on the stage, and creator of a new industry, summed up his years:

“What more could any man ask for?” he said. “A wonderful family, a host of friends, a big business, plenty of money … and not a dishonest dollar in the lot!”

Bill Francis is the senior research and writing specialist at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

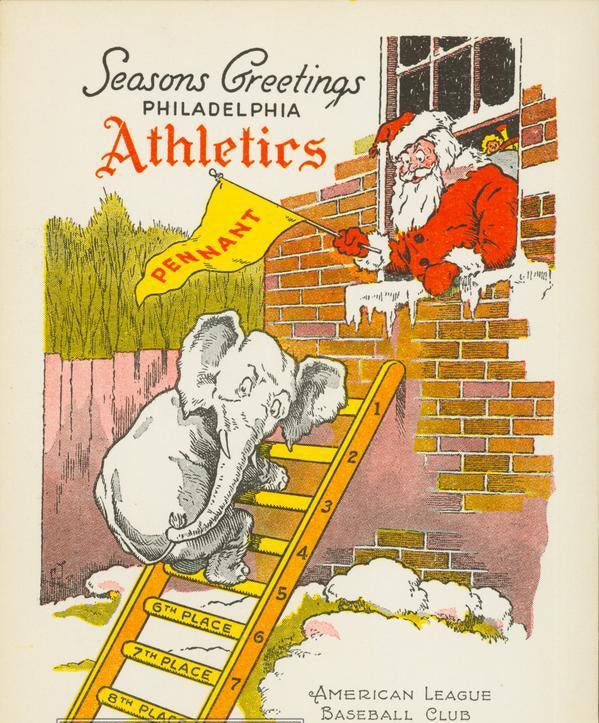

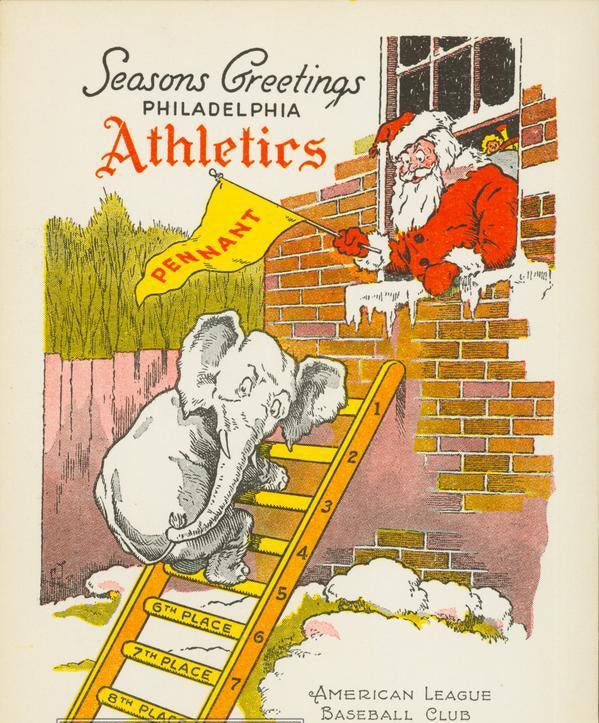

#Shortstops: Holiday wishes, Philadelphia style

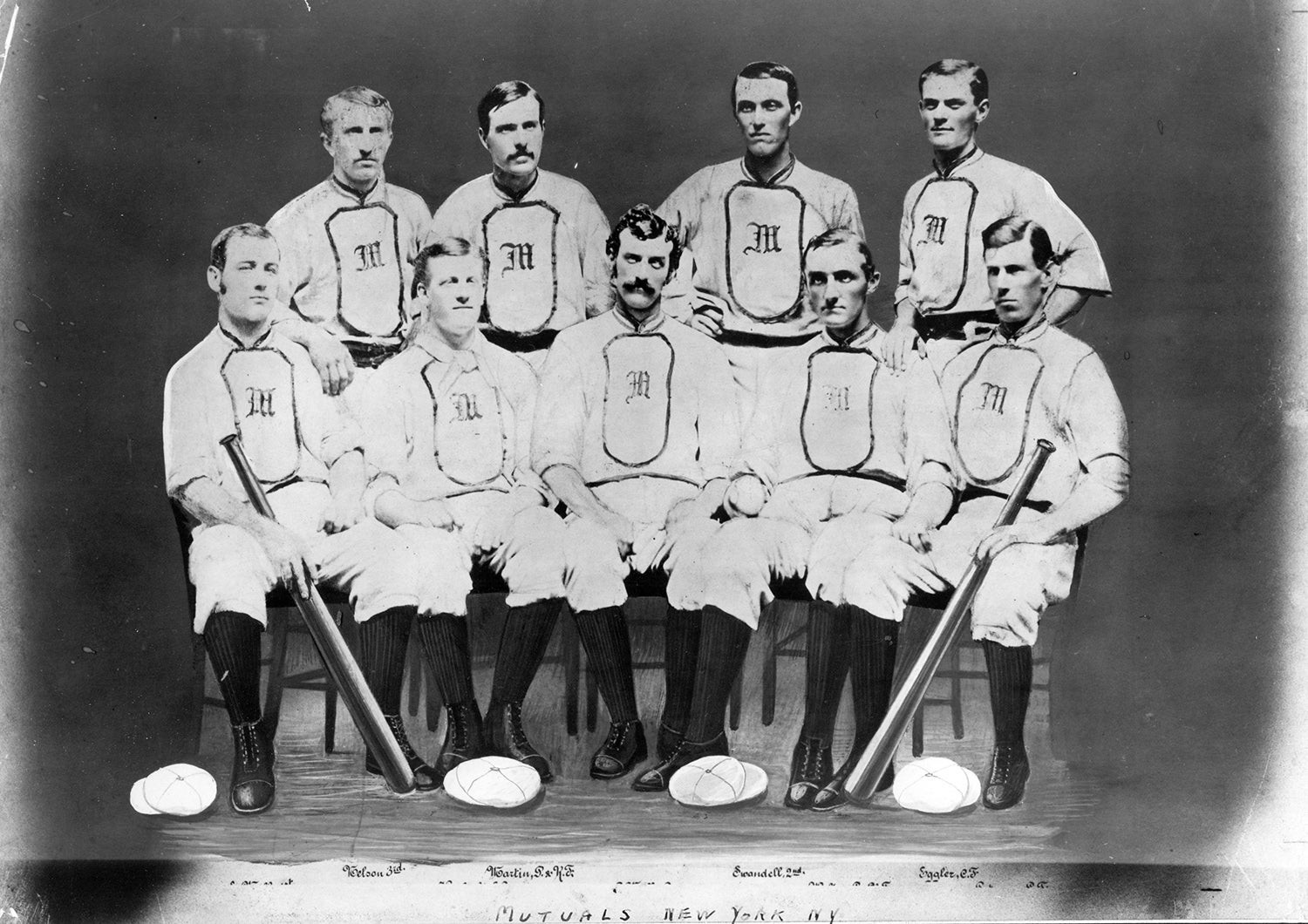

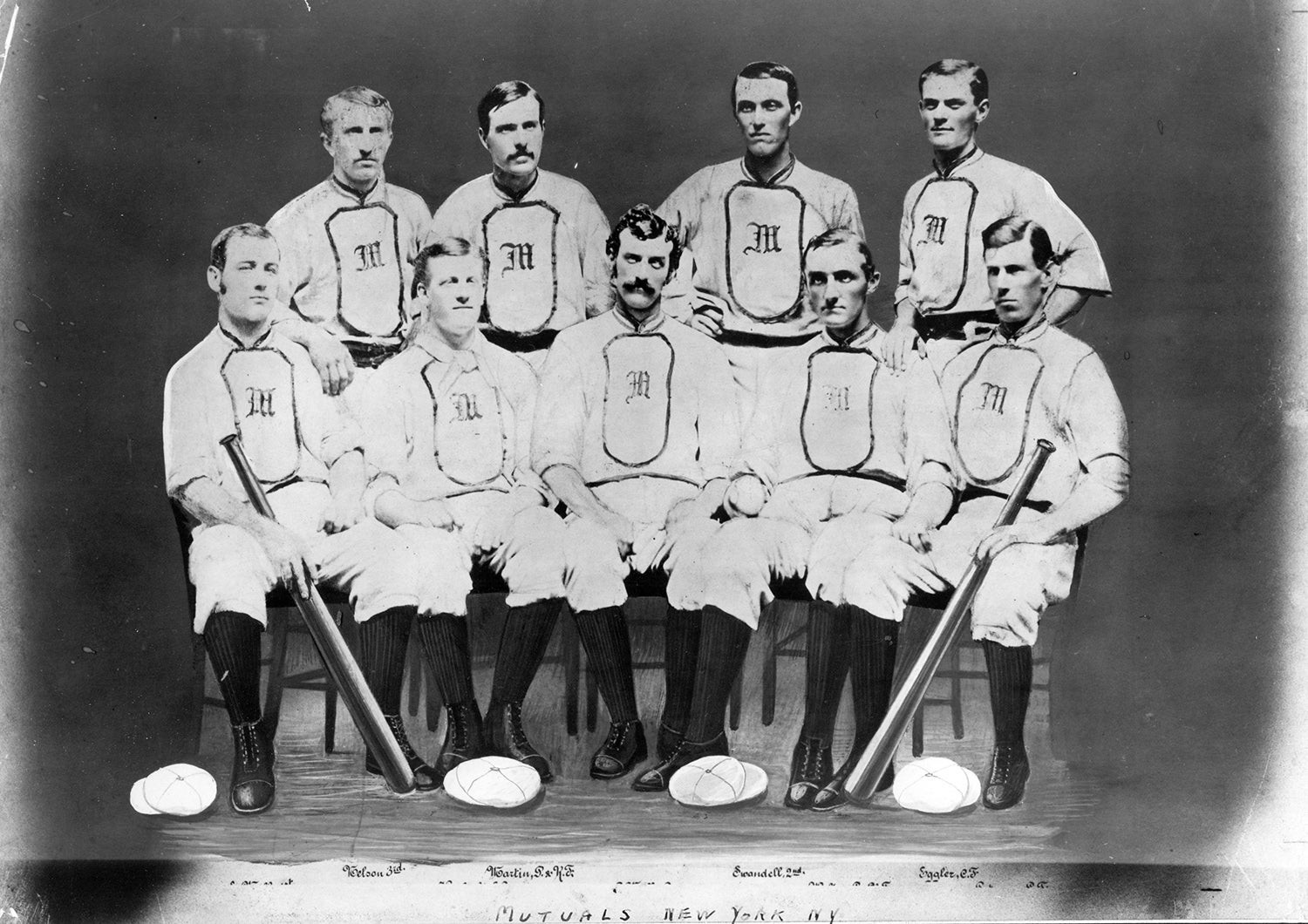

#Shortstops: Keeping score 19th century-style

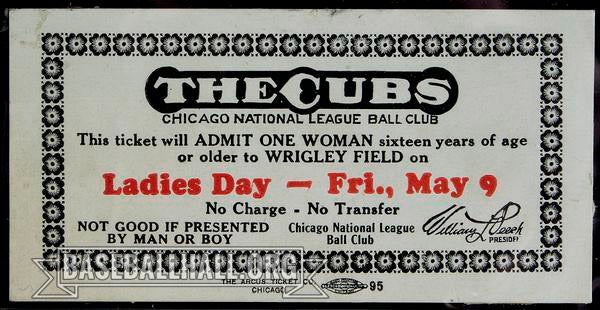

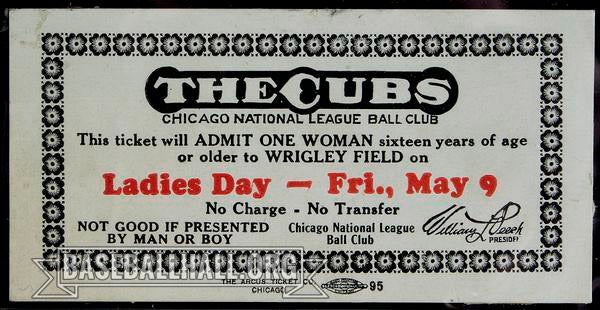

#Shortstops: Ladies Day promotions gave women the chance to cheer

#Shortstops: Printed history

#Shortstops: Holiday wishes, Philadelphia style

#Shortstops: Keeping score 19th century-style

#Shortstops: Ladies Day promotions gave women the chance to cheer