- Home

- Our Stories

- #GoingDeep: Gardella’s lawsuit pushed baseball’s labor boundaries

#GoingDeep: Gardella’s lawsuit pushed baseball’s labor boundaries

For as long as Major League Baseball has been around, people have wrestled with how to treat it in a legal setting.

Two of the most monumental pieces of U.S. legislation were the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 and the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914, which outlawed activities that inhibit interstate commerce and competition. These acts were at the center of lawsuits throughout the 1900s that attempted to define how antitrust laws applied to baseball.

In the 1940s, the actions of Danny Gardella and 21 other MLB players who jumped to the Mexican League spotlighted this relationship between MLB and antitrust laws, helping to move the needle on players’ autonomy and negotiating power.

The story of Gardella’s battle with baseball is told through documents preserved in the Hall of Fame Library.

Official Hall of Fame Merchandise

Hall of Fame Members receive 10% off and FREE standard shipping on all Hall of Fame online store purchases.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

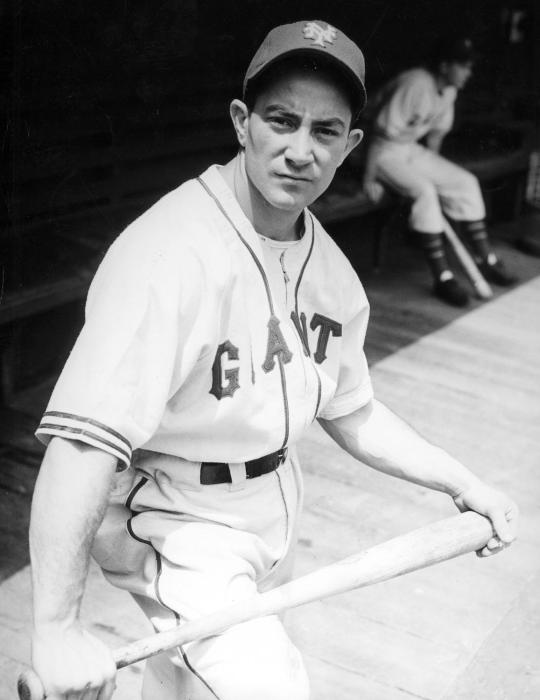

Born in the Bronx, N.Y., in 1920, Gardella began playing for minor league clubs after he was signed by the Detroit Tigers in 1938. After bouncing around the minors, Gardella quit professional baseball in 1940 and returned to New York, where he took on odd jobs and played in a shipyard baseball league. The New York Giants soon took notice of Gardella’s ability and signed him in 1944, and he debuted in the big leagues later that year.

Gardella broke out in 1945, socking 18 homers and driving in 71 runs while batting .272. He appeared to have developed into a bona fide Major Leaguer, but there was one problem – many of the game’s biggest stars were fighting in World War II, including Giants first baseman and future Hall of Famer Johnny Mize.

“It seems like nothing went right after all the good players, Willard Marshall and Sid Gordon and Johnny Mize, came back from the service,” said Gardella in a 1980 interview.

With Mize reclaiming his old position in Spring Training of 1946, Gardella was looking at a probable minor league assignment. He had also tried and failed to get a raise for 1946; he felt that his 18 home runs in 1945 established him as a power hitter worth more than a $5,000 salary, but the Giants did not oblige him.

“I feel that had things gone better politically, I would have done much better on the Giants,” Gardella said. “But there seemed to be a force pulling me in the other direction. There was an unpeacefulness ... There was a great lack of communication in the Giants’ front office. It was with everyone. It was as though they were afraid to communicate, because they knew basically that you work for them and you wanted something.”

A new opportunity soon presented itself to Gardella. At that time, the Mexican League was led by powerful businessman Jorge Pasquel, who wanted to increase the league’s popularity by wooing major leaguers to Mexico with promises of higher salaries than they were making in MLB. Frustrated with the Giants, Gardella contacted Pasquel, who offered him a salary nearly double his MLB earnings, and went to play in Mexico in 1946.

MLB Commissioner Happy Chandler was not pleased by the Mexican League poaching players from the big leagues. In June 1946, he banned any MLB players who had gone to play in Mexico from returning to the major leagues for five years. Chandler’s ban cited the reserve clause, which stated that players signed by an MLB team were contractually bound to their clubs until they were traded, released or retired.

Even with this ban, Gardella enjoyed life in Mexico and playing non-MLB ball. In 1947, while he was playing in Staten Island for the semipro Gulf Oilers, a telegram from the Commissioner was read over the loudspeaker stating that anyone caught playing with Gardella or any other Mexican League jumpers would never be allowed to play baseball in the major leagues. This proclamation accompanied resentment among Mexican players that the former MLB players received much higher salaries than they did.

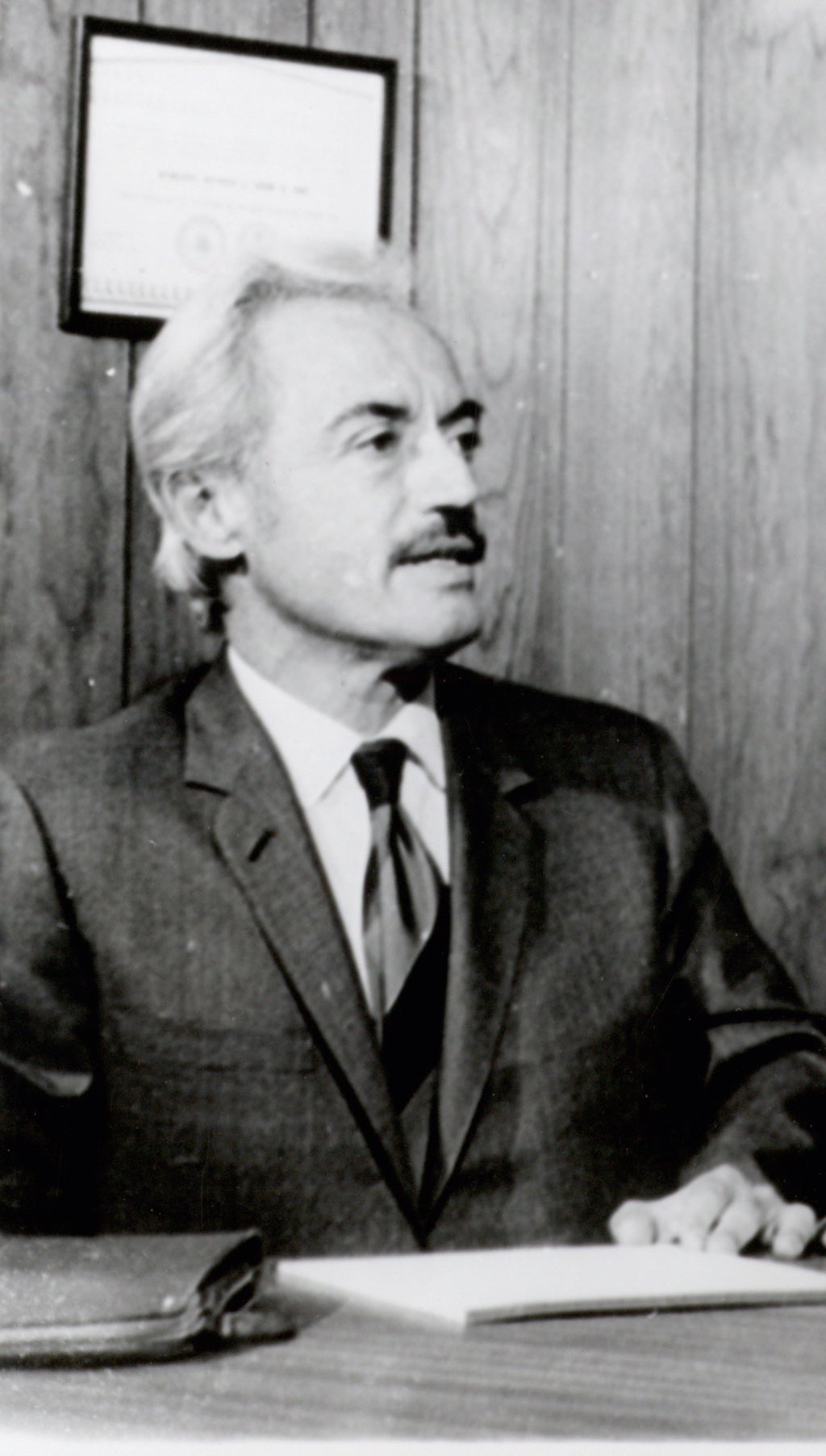

Soon afterward, Gardella hired a lawyer, Frederic Johnson, and sued MLB for $300,000, claiming they had deprived him of his livelihood and were illegally restricting trade by banning him and the other 21 MLB-turned-Mexican Leaguers from the major leagues via the reserve clause. Along with the reserve clause, this lawsuit questioned other then-standard aspects of player contracts, including player service rights, contract renewals and the club’s right of termination.

Initially, it appeared as if Gardella’s case might be over quickly. A federal judge ruled against Gardella, citing a 1922 United States Supreme Court ruling regarding the already-defunct Federal League which had ruled that “organized baseball” was not interstate commerce and therefore not subject to antitrust laws.

This case, which was the standard for the Gardella lawsuit and several subsequent lawsuits concerning MLB’s labor practices, stated that what made baseball “interstate” was teams’ travel between states, which was not part of the sport’s inherent nature and was an “incident” of baseball rather than the thing itself. It also based its ruling on insurance cases that, at the time of their ruling, deemed that insurance was not interstate commerce.

However, a lot had changed in the world of both baseball and interstate commerce between 1922 and 1947. Radio and television broadcasts, both of which generated significant revenue for MLB and traveled across state lines, were widespread by this time. Several of the insurance lawsuits cited in the 1922 case had been overruled, making the basis for the 1922 ruling essentially null and void. Additionally, cases such as Ring vs. Spina in 1945, which ruled that traveling theater shows were interstate commerce, further narrowed the gap between the rustic image of “America’s Pastime” and a powerful corporate conglomerate.

These differences between 1922 and 1947 suggested that the definition of “interstate commerce” might have changed over time, and those following Gardella’s case agreed. In February 1949, a federal appeals court ordered a full jury trial to revisit the issue. This did not please baseball executives; Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey said that players who opposed baseball’s antitrust exemption “leaned to Communism.”

MLB dropped the five-year ban in June 1949, and several players who had jumped to Mexico returned to their major league careers. Max Lanier played five more big league seasons and went on to manage in the minors. Fred Martin lasted two more seasons in the majors with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1949 and 1950 before retiring.

Gardella and his lawyer continued to hold out, and he did not return to MLB that season. Finally, in October 1949, Gardella dropped his lawsuit in exchange for a cash payment of $60,000 – about $700,000 in 2021 dollars.

At the time, the settlement effectively made Gardella one of the highest-paid players for any one year in baseball history.

“I think [my lawyer] Johnson was wise enough to realize that if we didn’t settle, baseball would have been considered such a darling that we never could have won,” Gardella told the Los Angeles Times in 1994.

Gardella returned to the majors in 1950, joining Martin on the Cardinals, and had one more MLB at-bat on April 20 in a game that also featured Martin pitching in relief. Gardella flied out to right in the eighth inning, was sent to the minors for the rest of the season and announced his retirement in October 1950.

“When I got on the Giants and played those two years, it seemed as though those two war years were the thing that I lived for: Baseball,” Gardella said in 1980. “I had felt that a culmination in my own life had occurred … I had gotten that little bit of honey, the culmination of baseball fame that I had sought and dreamed of as a child. So in a sense, my dream had come true.

“It was fulfilling and proper that I should have been just a wartime player, because that was the role, apparently, fate had fitted me for.”

While Gardella’s days fighting for players’ rights were over, he briefly pursued a vaudeville career, continuing his lifelong love of singing, before settling into a series of blue collar jobs.

But the scrutiny of MLB’s labor practices continued. The same year that Gardella retired, minor league pitcher George Toolson filed an antitrust action against MLB.

Toolson’s lawsuit stemmed from the 1949 season, when he was dropped from a Triple-A MiLB team to a Class A team after some reshuffling in the New York Yankees’ minor league system. He refused to report to the Class A Eastern League and was placed on the ineligible list, preventing him from signing with MLB-affiliated teams. In 1953, Toolson’s case made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, which dismissed it on the grounds that organized baseball was not subject to antitrust laws due to its “unique and anomalous characteristics.”

At the time of this ruling, many players and executives still felt that the reserve clause was necessary for traditional baseball to survive, and several players who testified before a Congressional committee in 1952 expressed this sentiment. Though the Toolson case did not eliminate the reserve clause, it highlighted another issue: MLB had not expanded into any new geographic areas for 50 years.

Soon afterward, five teams changed cities from 1953 to 1957, bringing MLB’s presence into Kansas City, Milwaukee, Baltimore, Los Angeles and San Francisco.

The Toolson ruling also reflected the desire of Congress and the Supreme Court to keep the minor leagues, which had been declining in scope and attendance throughout the 1950s, intact. The strength of Minor League Baseball and its affiliation with MLB differentiated MLB from other sports leagues who sought antitrust exemptions, such as the NFL.

In 1957, the Radovich vs. National Football League case made it to the Supreme Court, which declined to extend baseball’s antitrust exemption to football. The following year, the House passed an amendment to antitrust laws that extended baseball’s antitrust exemption to football, basketball and hockey, but that bill died in the Senate.

Gardella’s playing career may have been curtailed by jumping to the Mexican League and his subsequent lawsuit, but he lived to see the sport implement massive changes to its labor structure that were rooted in his battles. In 1969, Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood sued MLB after refusing to accept a trade to Philadelphia, challenging the reserve clause once again. While the Supreme Court ruled against him in 1970, it affirmed that baseball had changed significantly since the 1922 Federal League case and that this issue would have to be solved in Congress, not the Supreme Court.

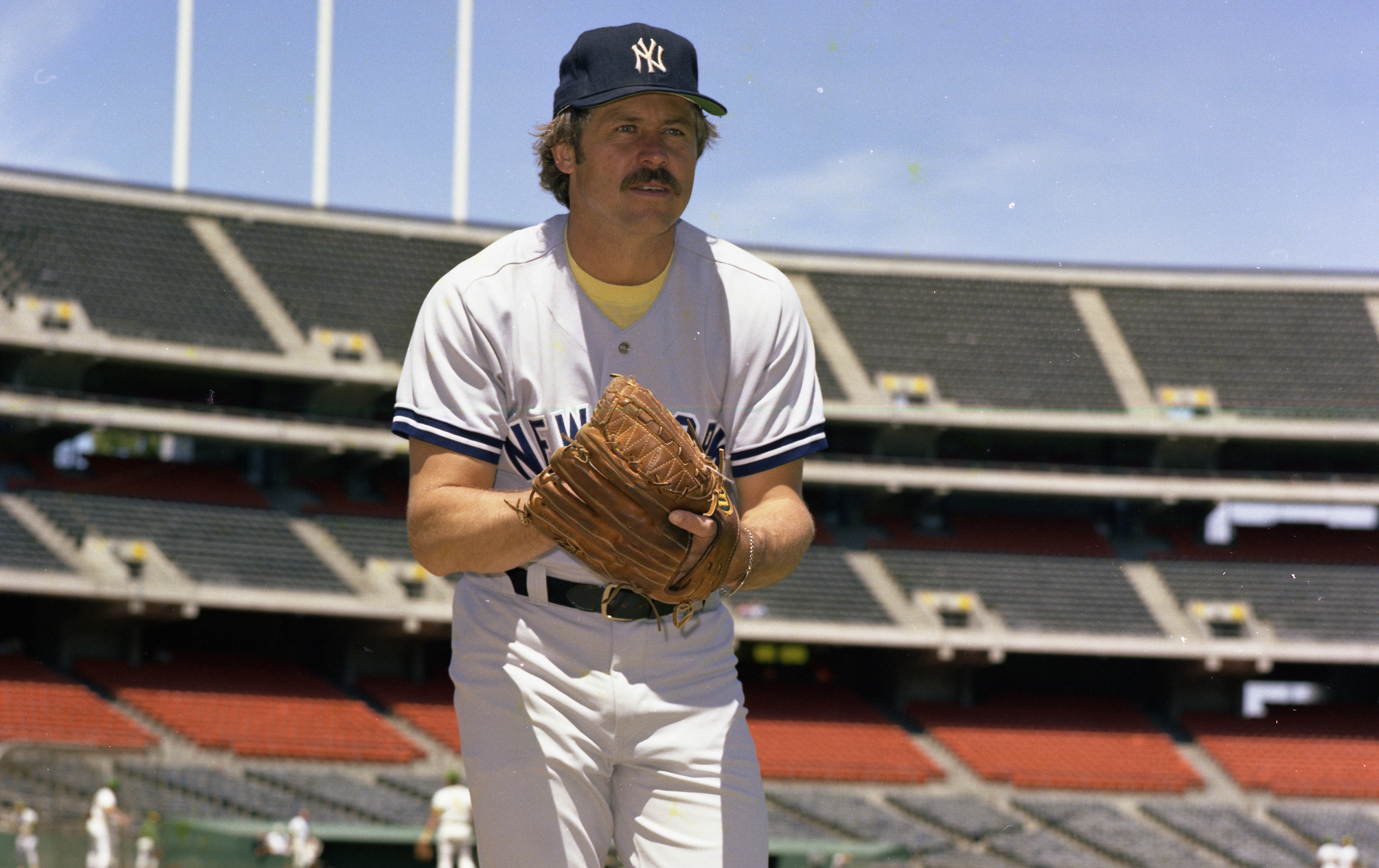

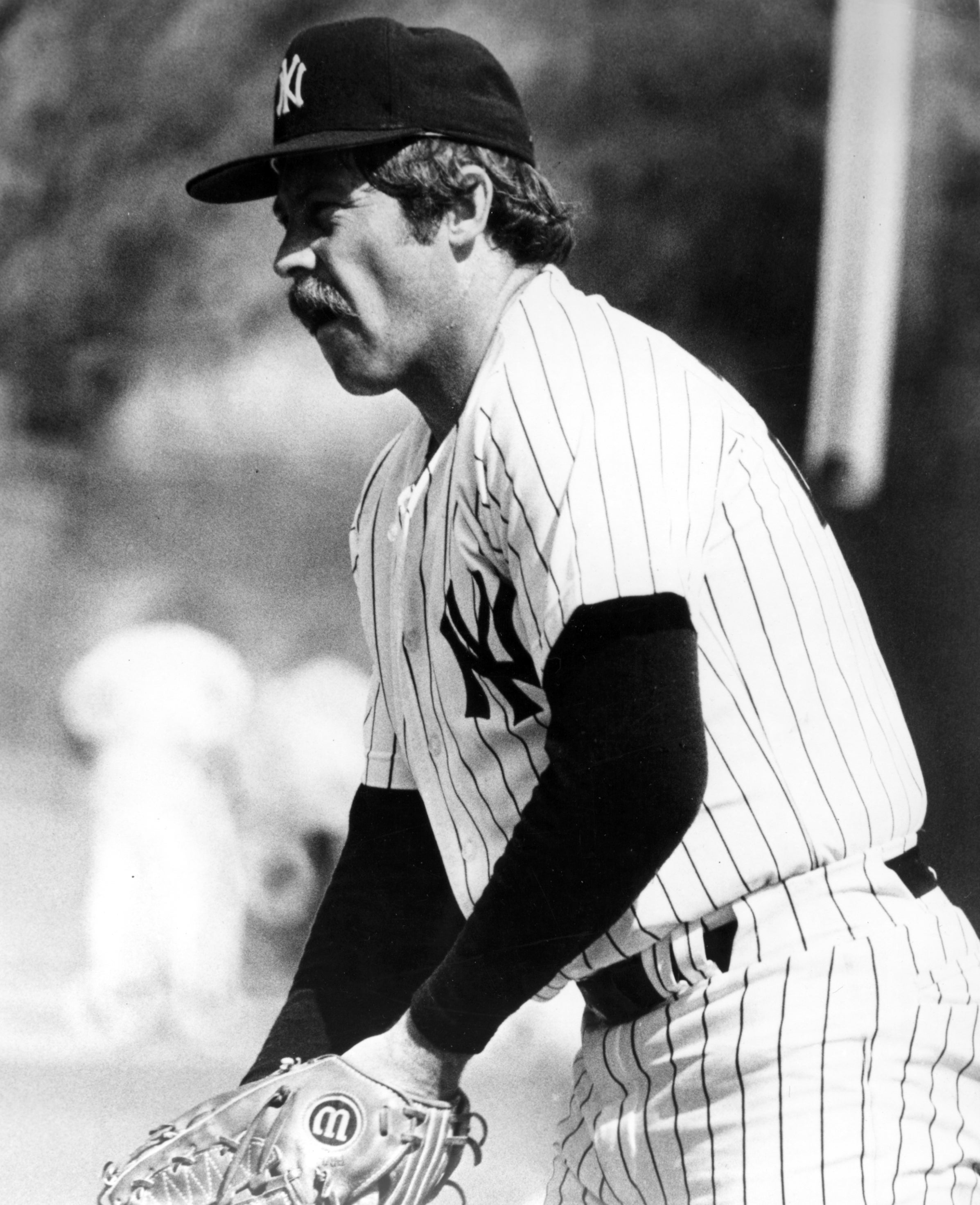

Gradually, negotiations between the MLB Players’ Association, led by Marvin Miller, and the owners chipped away at the reserve clause. In 1975, the labor landscape dramatically shifted after Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally were granted free agency by an independent arbitrator, Peter Seitz. He ruled that since neither player signed a new contract after their clubs picked up their options for 1975, those teams could not renew their contracts in perpetuity and both players were now “free agents.” This broke a tradition in which owners assumed that the reserve clause meant that teams could continually renew contracts for one year at a time.

In 1976, MLB and the MLBPA agreed that players with six years of Major League experience could become free agents. In 1998, a year after Flood passed away, Congress passed the Curt Flood Act. It revoked baseball’s antitrust exemption for MLB labor practices and officially abolished the reserve clause for players with over six years of MLB service time.

Gardella passed away in 2005 at age 85. Though he never reaped the benefits from the labor battles that he spearheaded in the '40s, he helped dismantle baseball’s reserve clause and usher in higher player salaries, free agency and greater negotiating power for the MLBPA.

“All of these things strangely tied in together to form a strange magic carpet of destiny, which I rode into the arena of having to sue [MLB],” Gardella said in 1980. “It was as though steps were leading up to it.

“It had a sort of Alexandrian, or you might say, a destiny-marked epoch, like Napoleonic. I’m not trying to really say that I’m a man of destiny, but it was very coincidental that certain things happened. It’s very strange really.”

Elizabeth Muratore was a membership intern in the Hall of Fame’s Frank and Peggy Steele Internship Program for Youth Leadership Development. She currently works for MLB and has written for MLB.com, Rising Apple, Girl at the Game and the IBWAA.

Related Stories

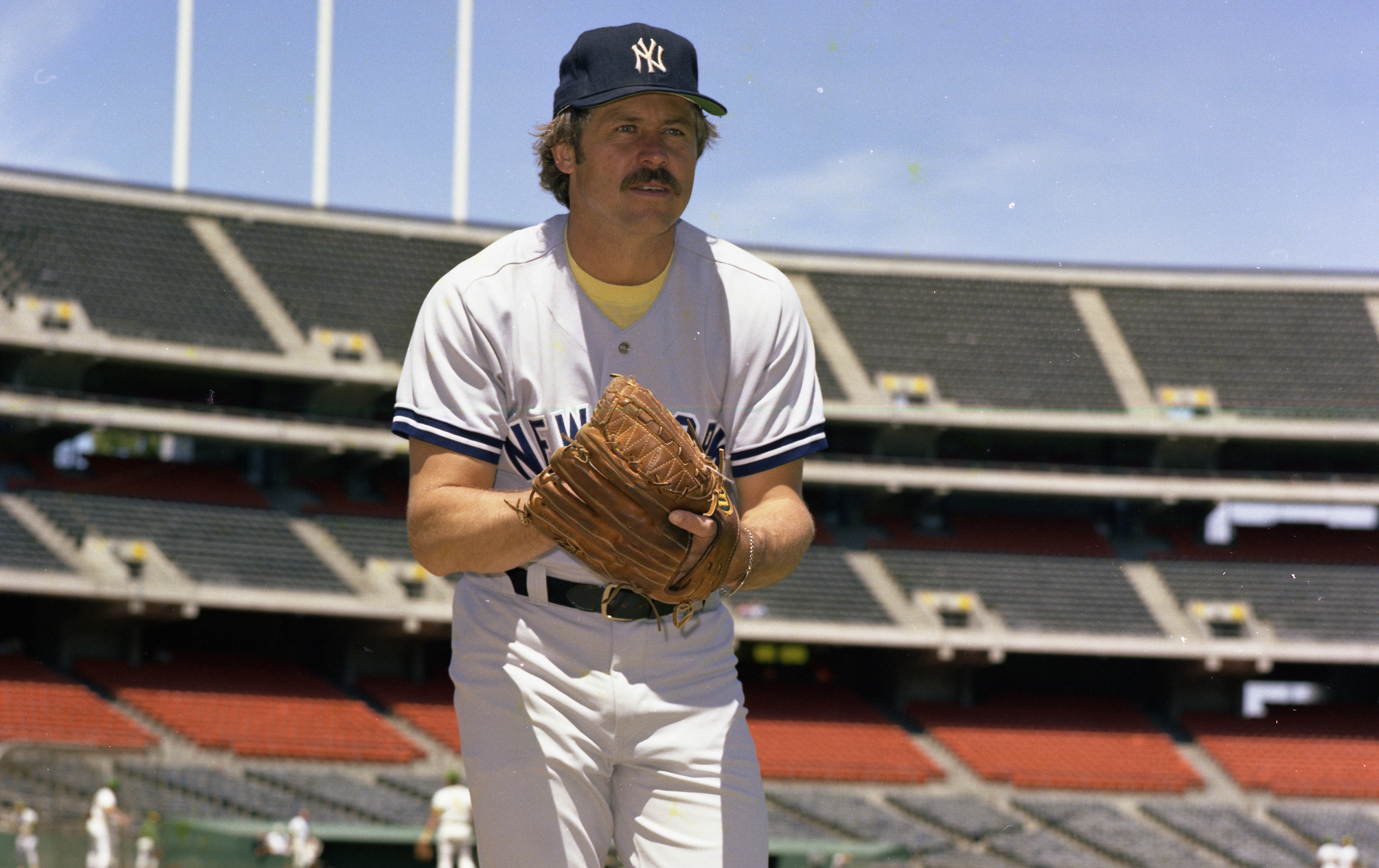

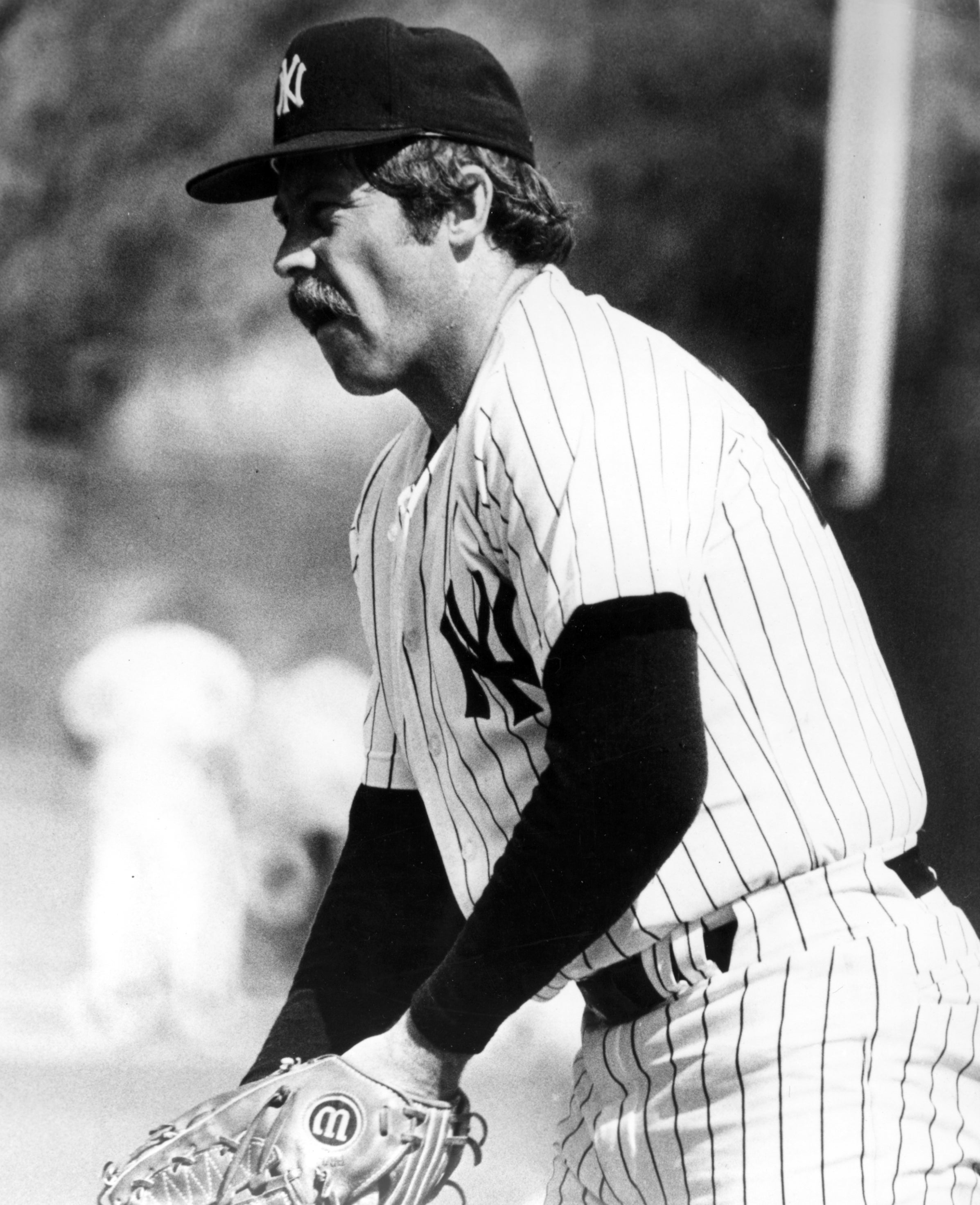

Hunter helped usher in free agency era

Catfish Hunter signs free agent contract with New York Yankees

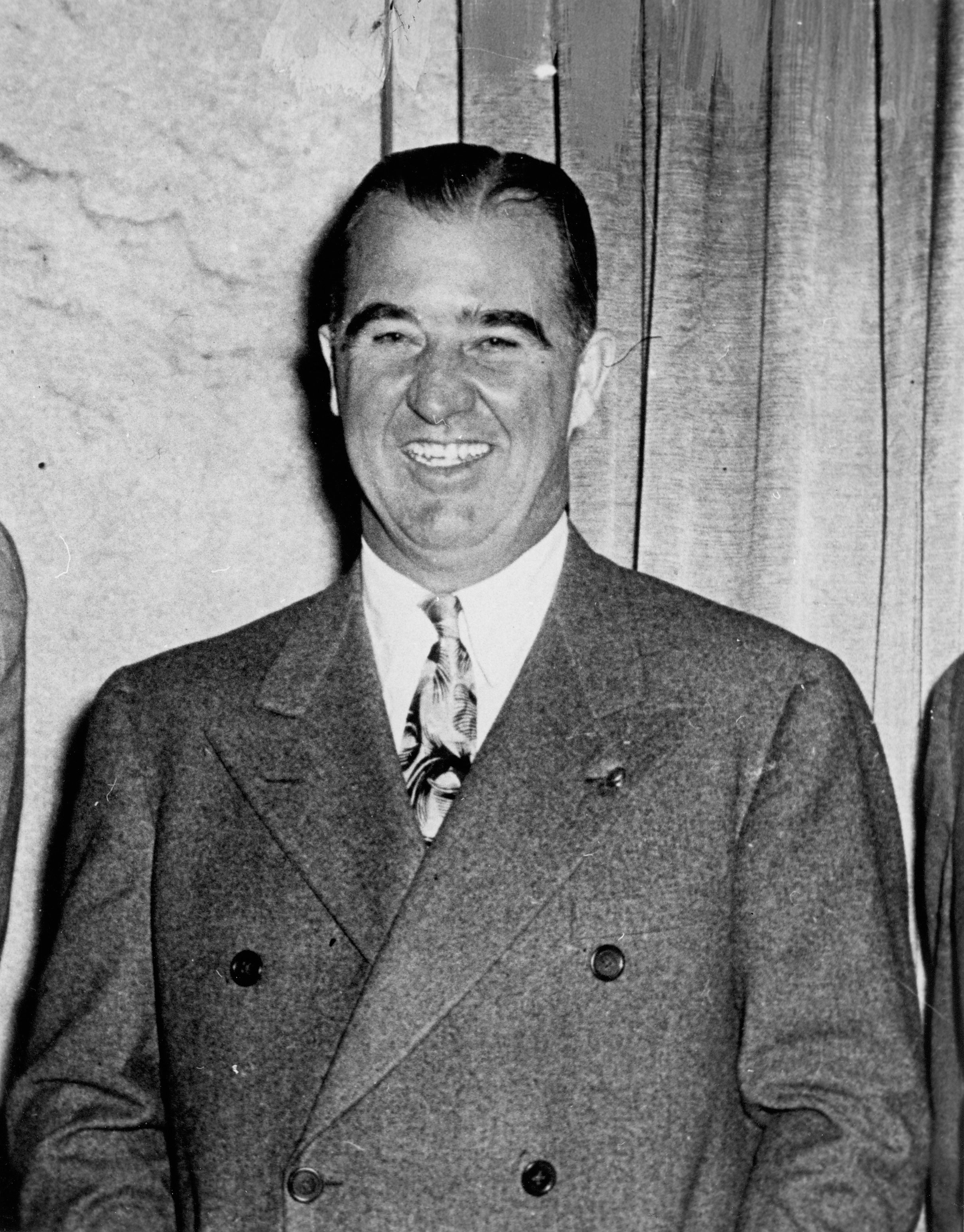

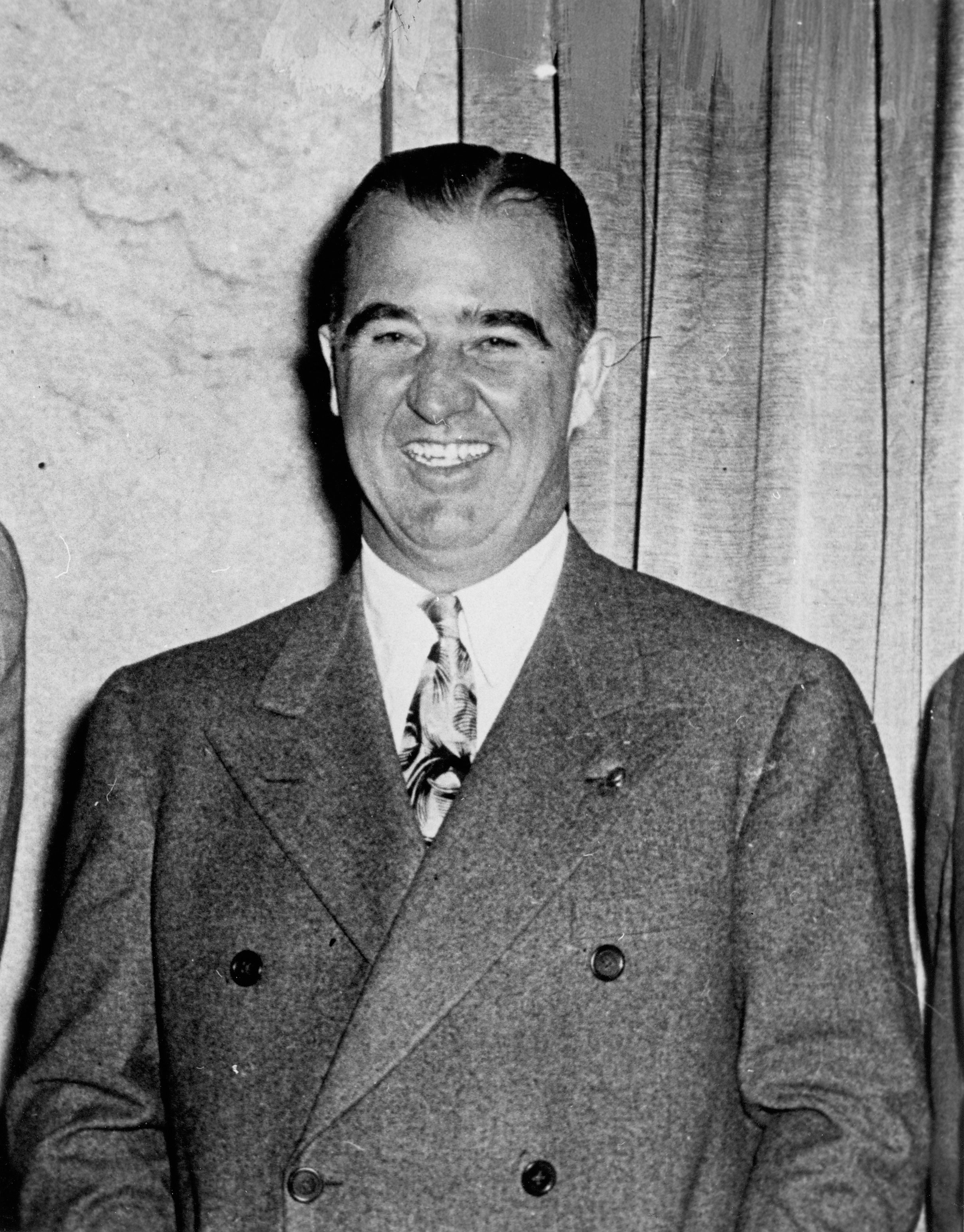

Chandler’s election changes future of baseball

Class of 1982 brought Aaron, Robinson, Jackson and Chandler to Hall

Hunter helped usher in free agency era

Catfish Hunter signs free agent contract with New York Yankees

Chandler’s election changes future of baseball