- Home

- Our Stories

- Dugout Trailblazer

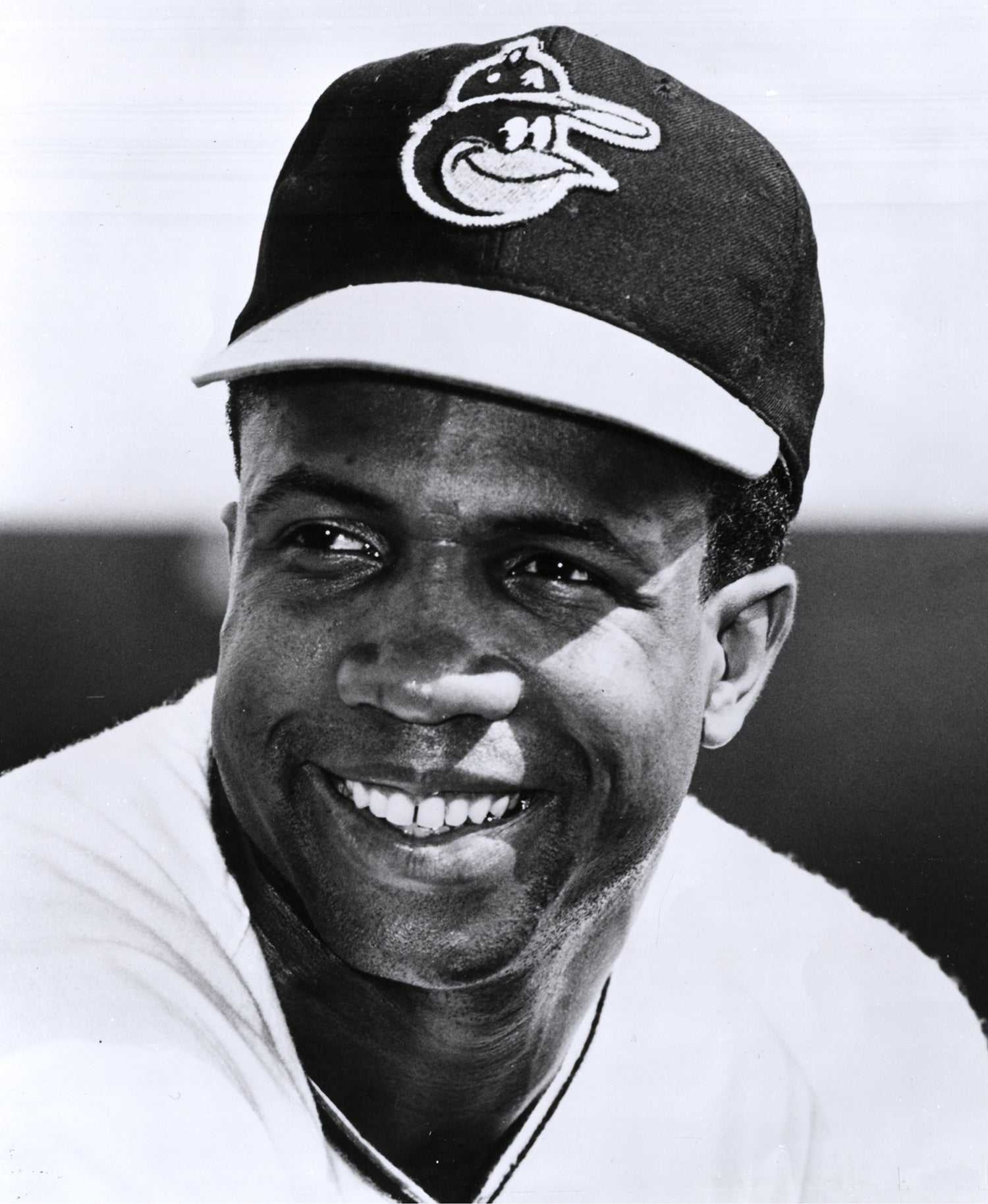

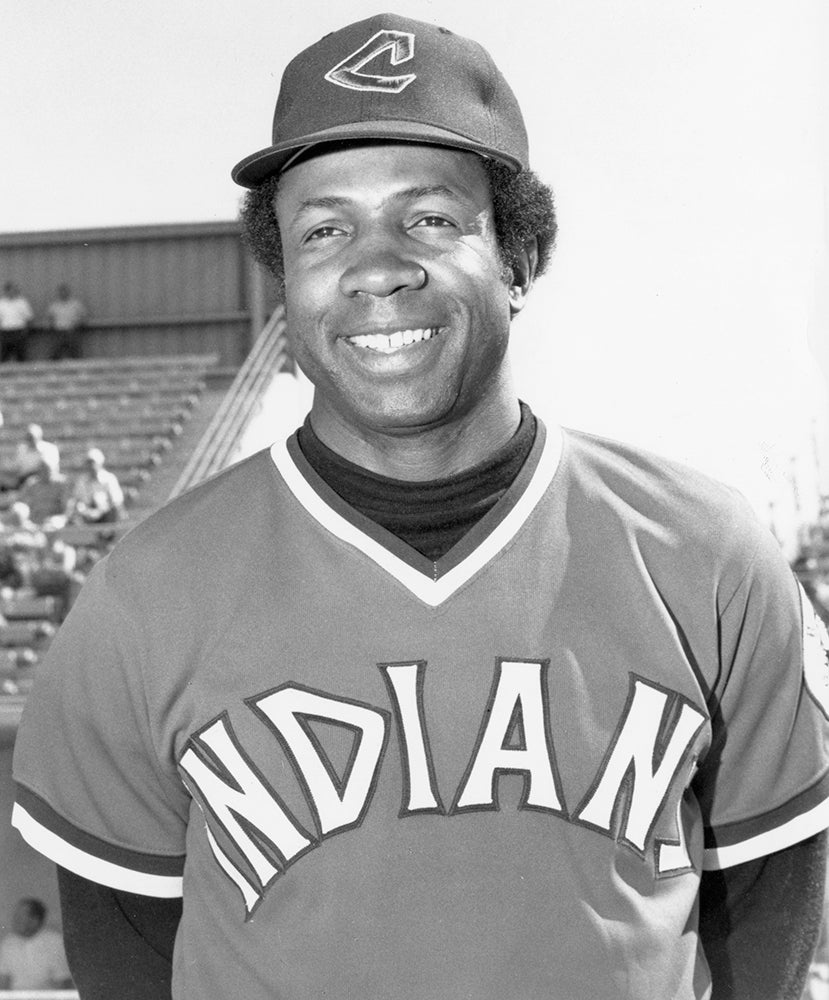

Dugout Trailblazer

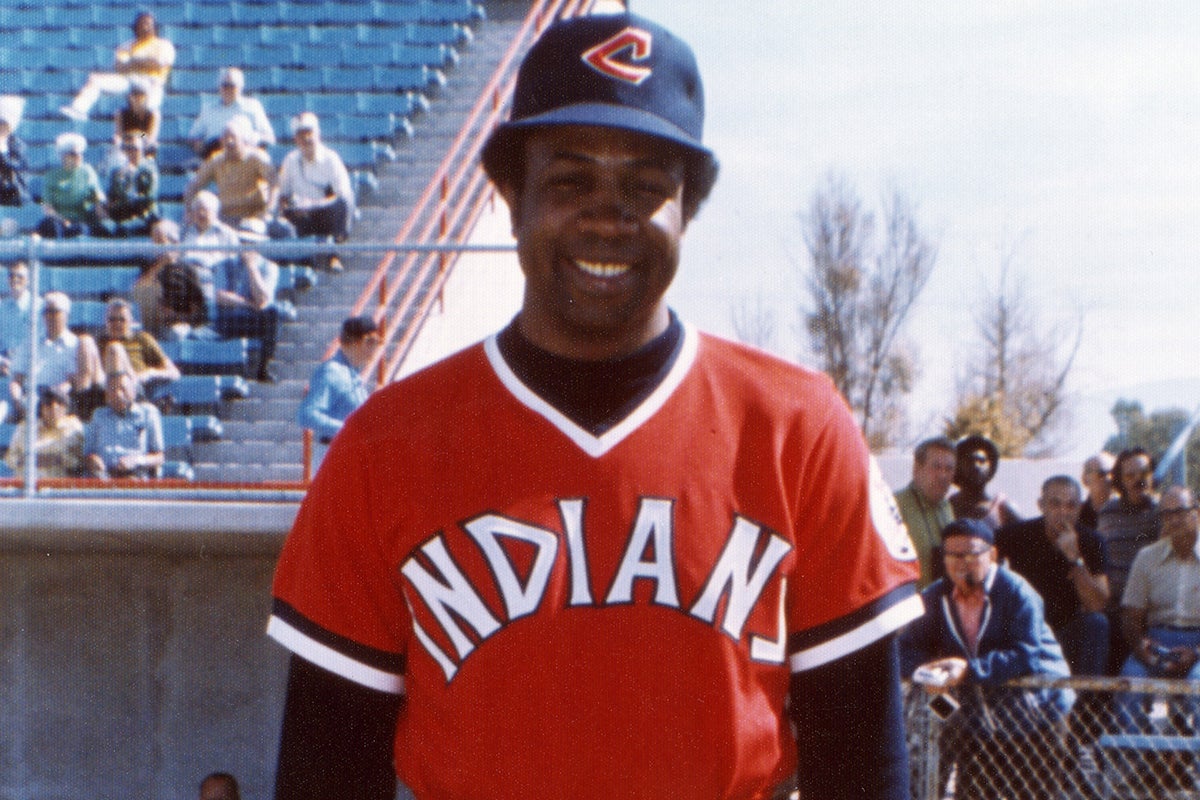

It’s difficult to fathom the pressure that Frank Robinson felt 50 years ago, as he prepared to become the first Black manager in the history of the American League. The emotional burden was enormous, given the game’s conservative nature and the continuing presence of a few old-line naysayers who still questioned whether a Black man could capably guide a major league team.

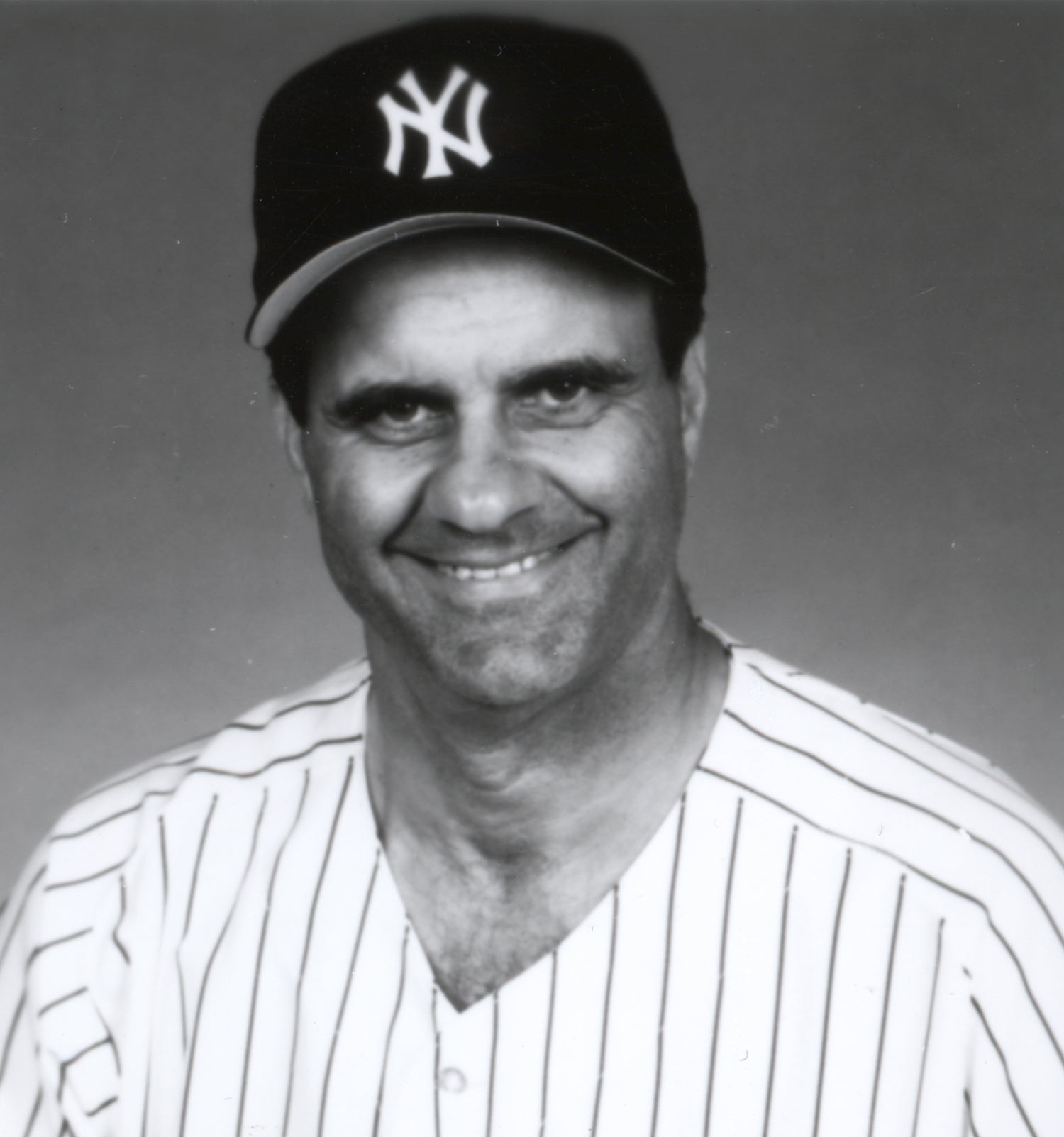

As if that atmosphere of stress and anxiety was not enough, Robinson also faced the added burden of being a player. Having officially been named manager at a press conference on Oct. 3, 1974, Robinson was not just set to serve the Cleveland Indians as their manager in 1975; he had also had another prominent role to fill as the team’s part-time designated hitter. By 1975, player/managers had become virtually extinct within the game. There were no other player/managers at the time, and the next player/manager would not arrive until 1977, when Joe Torre took on the dual role with the New York Mets.

Without question, Robinson faced a huge task, one that was made more difficult by Cleveland’s mediocrity on the field. In 1974, the Indians had finished with a record of 77-85, placing them a distant fourth in the American League East. And in a division featuring veteran teams in Baltimore, New York, and Boston, there seemed to be little hope of the Indians emerging as a strong contender in 1975.

On the other hand, Robinson was well prepared for his first managerial go-round in the American League. As a player, he had long been regarded as one of the game’s smartest and toughest competitors, as well as a clubhouse leader. He had also managed several seasons in Winter League ball, where he honed his managerial skills while guiding both veteran players and younger prospects.

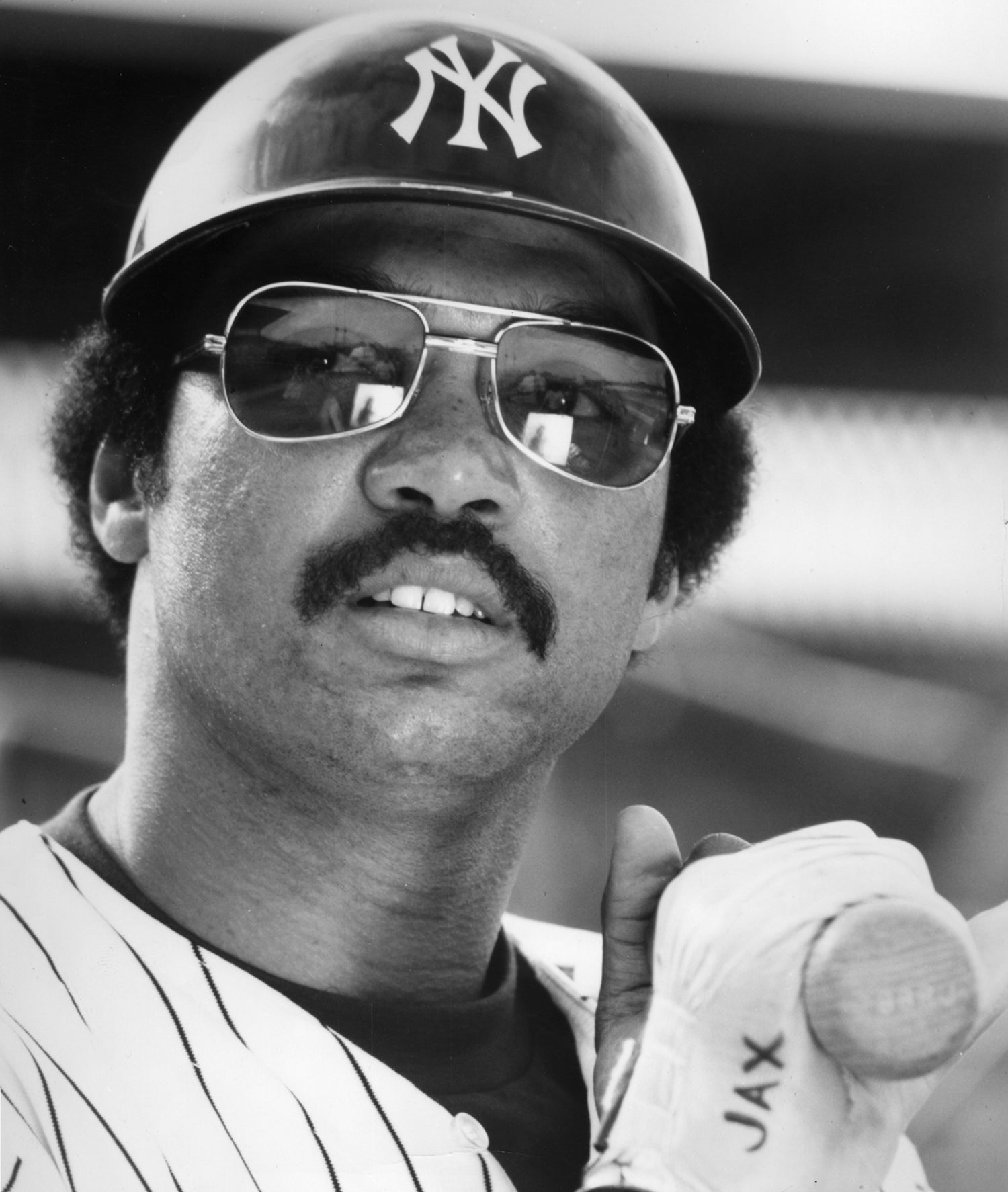

As a Winter League manager, Robinson drew praise for his toughness and his general approach to the game. One of his players in the Puerto Rican Winter League, a young Reggie Jackson, raved about Robinson’s calming, reasoned approach. Another Robinson quality, his ability to teach the game and its fundamentals, also drew positive reviews. That quality figured to help him in his first season at the helm of the Indians, a young team that would feature only two players in their 30s (Rico Carty and the newly acquired Boog Powell) as part of their everyday lineup.

Settling into Spring Training in Tucson, Ariz., Robinson announced a few changes in managerial policy, including the elimination of a curfew for his players, in contrast to past Indians practice. But he also made it clear that he had no interest in becoming a buddy to his players. Even though he was still just 39 years and a contemporary to the players (and still technically their teammate), he believed that he needed to draw a line of separation. Robinson was not “one of the guys.” He was the boss, and his decisions would need to be respected.

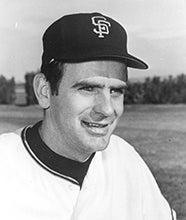

One of the players who did not always agree with Robinson’s methods was Gaylord Perry, the team’s ace and 21-game winner in 1974. During the spring, Robinson implemented a tougher conditioning program that emphasized running and stretching as a way of cutting down on injuries. He believed that all of his players needed to follow the regimen. One day, Robinson noticed Perry taking some shortcuts during his running routine. So he called the veteran pitcher into his office and questioned whether anything was bothering him. When Perry said there was nothing wrong, Robinson admonished his star pitcher, telling Perry that he didn’t appreciate his attitude. Robinson urged Perry, his most recognizable player, to set a better example for the younger players.

Perry later met privately with Indians general manager Phil Seghi to request a trade, but the GM instead arranged for a meeting involving himself, Perry and Robinson. The one-hour sit-down allowed the manager and pitcher to clear the air, at least for the rest of Spring Training.

After the blow-up with Perry, Robinson’s first Spring Training as manager proceeded without any other major incidents, setting the stage for the regular season. Robinson and the Indians made their way to Cleveland for their Opening Day game against the New York Yankees. Despite less-than-ideal weather conditions that included 36-degree temperatures, a large crowd of 56,715 fans gathered at Municipal Stadium on April 8 to see the historic debut of Robinson as manager. Those hardy fans also received a bonus, as Robinson penciled his own name into the lineup as the Indians’ DH.

Prior to the cold-but-sunny afternoon game, Robinson met with Seghi. According to Robinson, Seghi offered the following recommendation to him: “Phil suggested to me this morning, ‘Why don’t you hit a homer the first time you go to the plate?’”

In response, Robinson said, “You’ve got to be kidding.” Seghi almost certainly was joking, but his words would prove far more prophetic than anyone could have thought.

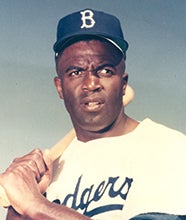

While Robinson’s immediate task at hand included both playing and managing, there were also reminders that placed the nature of this Opening Day in a larger perspective. To mark Robinson’s managerial debut, the Indians staged a 30-minute pregame ceremony. Several dignitaries attended, including Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. For Robinson, he was especially pleased that the ceremony included Rachel Robinson, the widow of Jackie Robinson, who had called for baseball to hire a Black manager just before his death in 1972.

According to Cleveland’s newly installed manager, Rachel’s presence at the ballpark kept his mind from straying. “I was very proud that (Rachel) would make the trip over there,” Robinson said. “I hoped and wished that Jackie could have been there. The next best thing was having her there.”

Earlier in the day, Robinson had focused on the task of filling out his first lineup card. In a manner contrary to many managers of that era, Robinson stacked the top of his batting order with his best power hitters, putting Oscar Gamble in the leadoff role, himself second, and the trio of George Hendrick, Charlie Spikes, and Boog Powell in the third, fourth, and fifth spots.

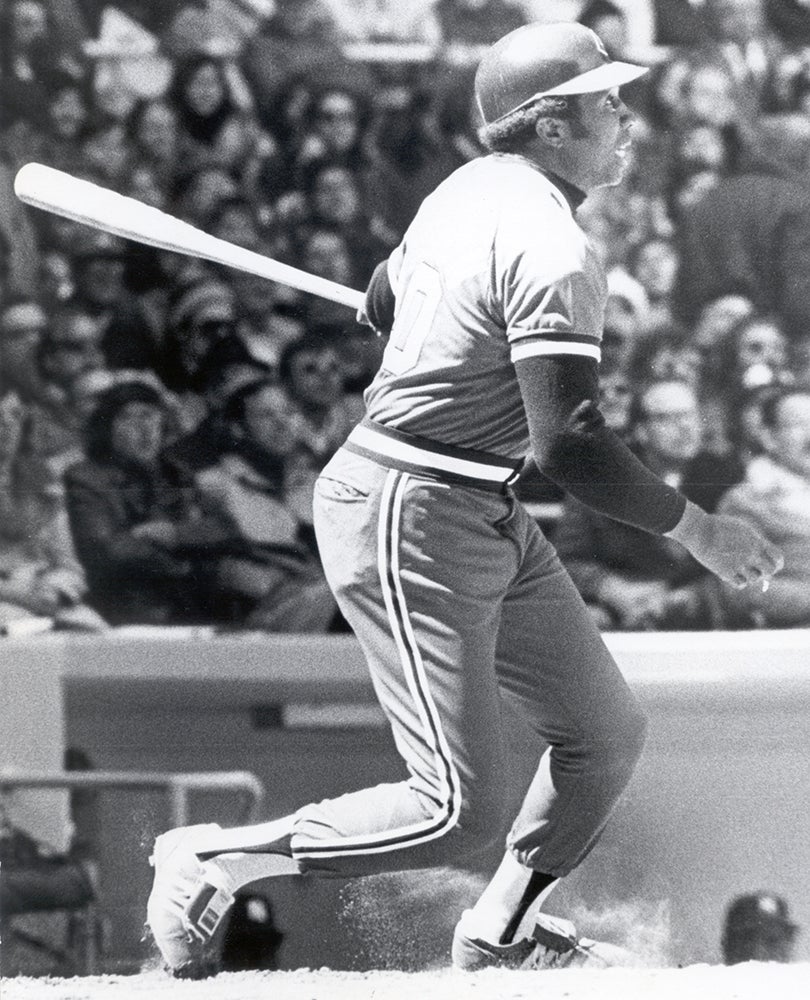

After Gamble started the bottom of the first with a foul pop to third base, Robinson stepped in to face Yankees right-hander George “Doc” Medich. Robinson fouled off three pitches in working the count to 2-and-2 before seeing a fastball low and away. It was not a bad pitch by Medich, but Robinson managed to pull it toward left field. Yankees outfielder Lou Piniella ran back to the wall and leapt, but the ball eluded his grasp and sailed into the seats. In storybook fashion, Robinson had managed to hit a home run in the first at-bat of his managerial debut – and make his general manager seem like a prophet.

As Robinson approached home plate, the fans at Municipal Stadium rewarded him with a roaring cheer. After tipping his cap to the crowd, he was immediately greeted by Gaylord Perry, Cleveland’s Opening Day starter and the man who had drawn Robinson’s ire during Spring Training.

“Any home run is a thrill,” said Robinson to a flock of reporters after the game, “but I’ve got to admit, this one was a bigger thrill.”

Robinson’s blast gave the Indians an early 1-0 lead, but it did not last long, as the Yankees responded with three runs against Perry in the top of the second. Those runs would prove to be the extent of the offense against Perry, who settled down and finished off a complete game effort. In the meantime, the Indians rallied behind the bats of the slugging Powell, who went 3-for-3 with a home run, and Jack Brohamer, who added two hits and two RBI. The Indians won, 5-3, making Robinson the victor in his debut.

The crowd at Municipal Stadium responded to the Opening Day win as if the Indians had clinched the pennant. In the top of the ninth inning, as Perry faced the Yankees’ Thurman Munson with two outs and a runner on first base, Robinson fought back some nervousness for only the second time that day (The first bout of nerves had come during the national anthem).

As the Municipal Stadium fans roared with each pitch, Munson battled Perry before hitting a routine tapper back to the mound. That resulted in the game’s final out – and a large commotion in the stands. As Russell Schneider wrote in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, the fans “gave the Indians a spinetingling ovation.”

The fans in Cleveland seemed to appreciate the significance of the game. It was not just an Opening Day win; it was a most fitting way to make history, with the first Black manager in the American League contributing both with his decision-making and his bat.

For Robinson, the day’s events had unfolded like a perfect script. “I couldn’t think of any better way to start my new career,” Robinson told the Associated Press. “I was extremely pleased by the way we won. It was a team effort. The guys came from behind and played together, and that’s what you have to do to be successful.”

As a team, the Indians would find more success in 1975 than they had in 1974, though it did not come easily. Robinson guided the Indians to a respectable record of 79-80, an improvement of three and a half games. It was also a tumultuous season, marked by frequent disagreements. In addition to the Spring Training incident with Perry, who would end up being traded in June, Robinson encountered dust-ups with Rico Carty and John Ellis. There were also many confrontations with umpires. Robinson brought his typical intensity and fire to managing, resulting in numerous on-field arguments and three ejections in 1975.

In later years, Robinson would calm his emotions, remaining old school in approach, but learning to curb his temper and select his battles more judiciously. Those adjustments helped him last for 16 seasons as a manager. In an era without wild card teams, Robinson would never lead a team to the postseason, but did earn two second-place finishes and took home American League Manager of the Year honors with Baltimore in 1989.

More significantly, in taking on the pioneering task of managing, Robinson served as a trailblazer for other Black managers. Those later managers would include Larry Doby, Maury Wills, Felipe Alou, Cito Gaston, Dusty Baker, and Dave Roberts, among others.

But for all of them, it was Frank Robinson who cleared the path.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Memories and Dreams

This story previously appeared in Memories and Dreams</em>, the award-winning bimonthly magazine exclusively available to supporters of the Museum's Membership Program.