- Home

- Our Stories

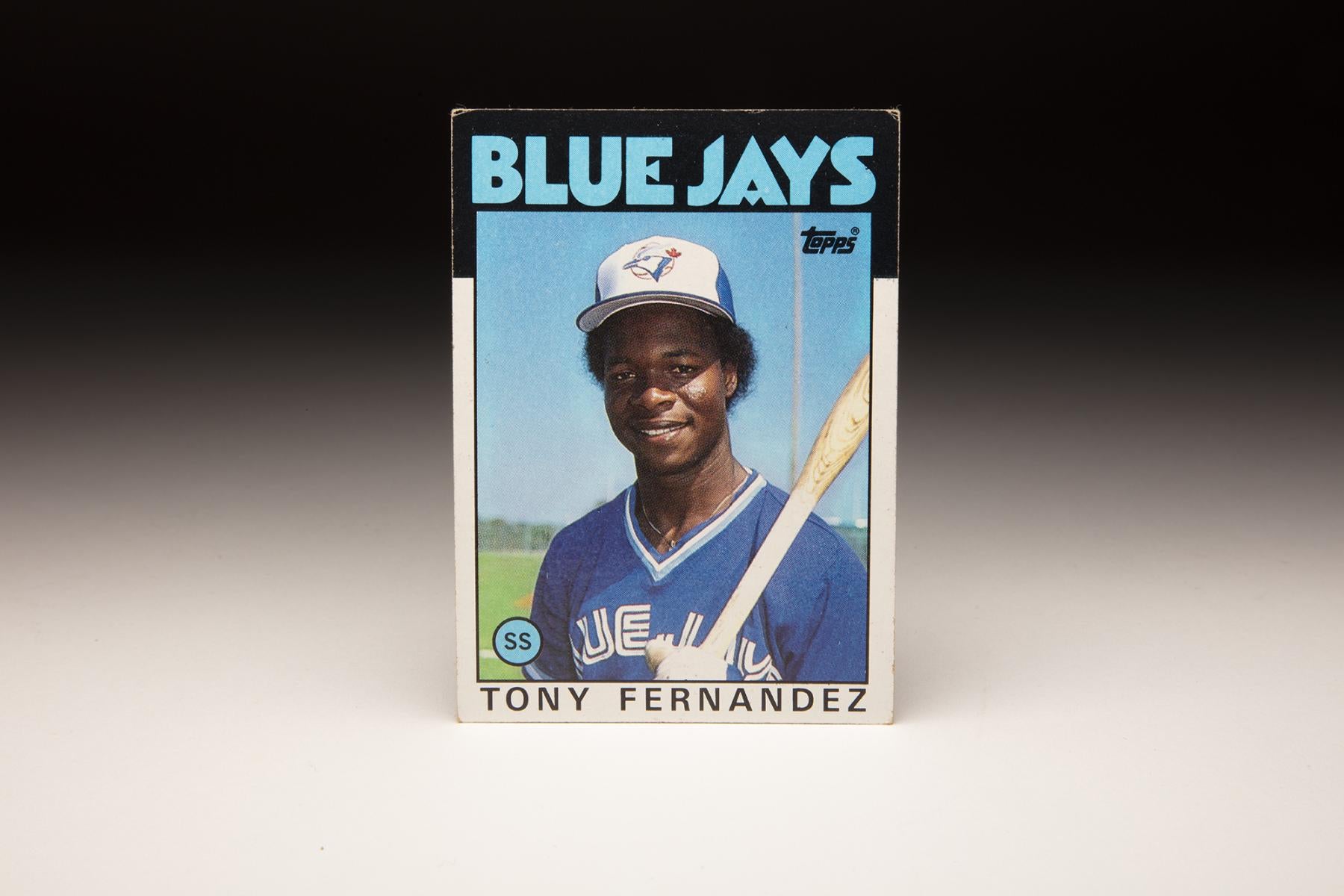

- #CardCorner: 1986 Topps Tony Fernández

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Tony Fernández

In 17 big league seasons, Tony Fernández became a magnet for big moments – some in his favor, others not as much.

But what was undeniably his was a talent for the game that – for a time – made him the prototype for big league shortstops.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

Official Hall of Fame Apparel

Proceeds from online store purchases help support our mission to preserve baseball history. Thank you!

Born June 30, 1962 in a town he helped make famous – San Pedro de Macoris, Dominican Republic – Fernández discovered baseball as a youngster. It was a path that would lead him out of the sugar cane fields and onto the world’s biggest stage.

“It’s no accident,” Blue Jays general manager and future Hall of Famer Pat Gillick told The New York Times in 1984 about the number of star players who came from San Pedro de Macoris. “In (the late 1950s), the Dominican government built three stadiums to the exact specifications of the Miami Stadium, where the Baltimore Orioles train. One was in Santo Domingo, the capital. Another in Santiago. The third in San Pedro.”

Fernández – like so many other children – spent his youth in that stadium.

“Tony was born in a house just past right field in the ballpark,” Blue Jays manager Bobby Cox said in 1984. “He was probably chasing a baseball when he was two years old.

“He’s already as good defensively as anybody in the big leagues.”

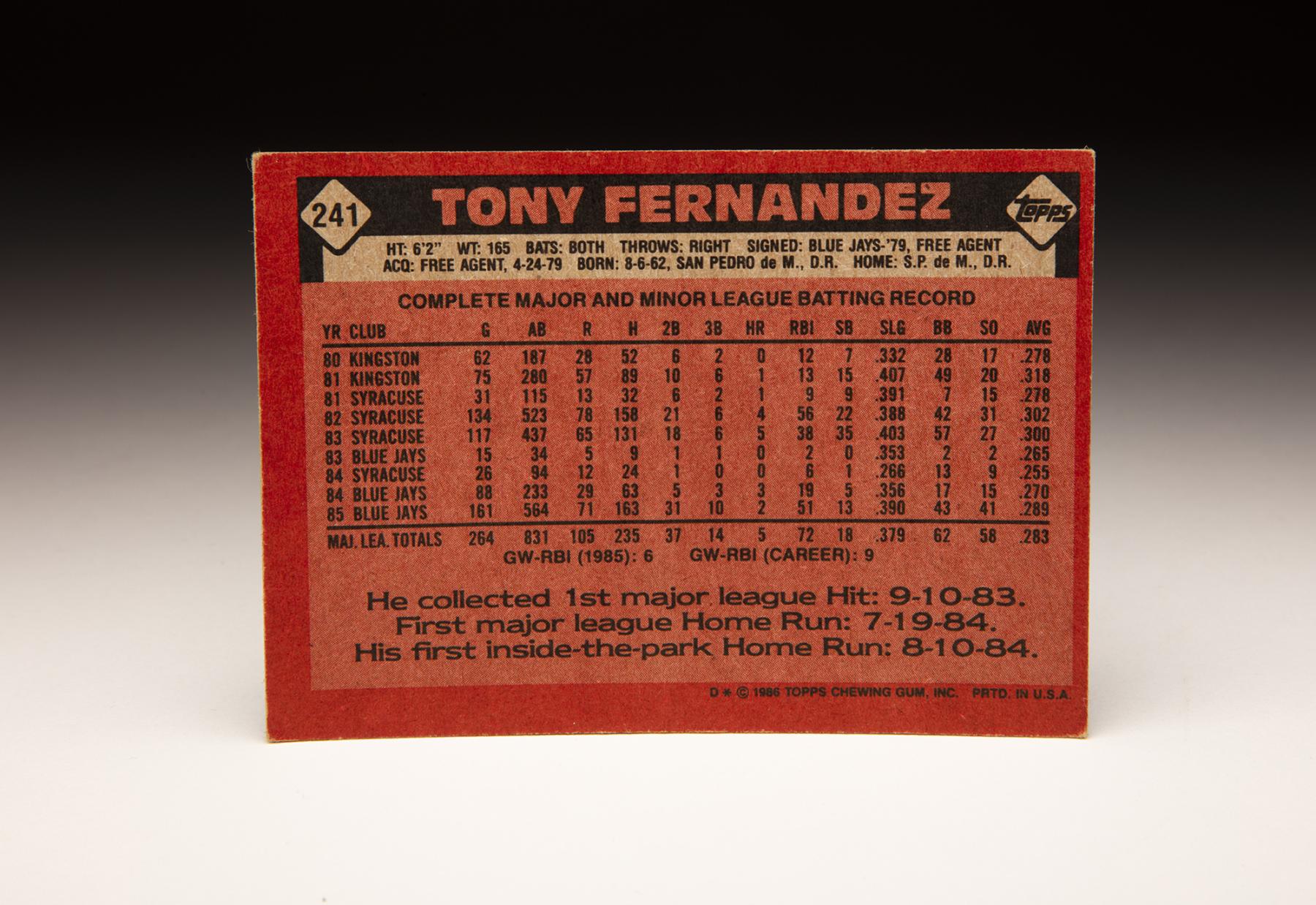

At just 16 years of age, Fernández signed with the Blue Jays on April 24, 1979. By 1982, the slender Fernández – generously listed at 165 pounds on his 6-foot-2 frame – was hitting .302 for the Blue Jays’ Triple-A affiliate in Syracuse. The next season, Fernández was named the International League’s Most Valuable Player.

Bobby Doerr, the Blue Jays big league hitting coach from 1977-81, called Fernández a future Hall of Famer before he ever got to the majors.

Debuting with the Jays in the final month of the 1983 season, Fernández was ticketed for stardom. But a broken left hand delayed the start of his 1984 season, limiting him to just 88 games.

The next season, the Blue Jays put it all together to win the AL East title, with Fernandez hitting .289 in 161 games. It was a near-perfect predictor for his career, where the switch-hitting Fernandez hit .288 – .289 as a lefty and .286 as a right-hander.

By 1986, Fernández was widely regarded as the game’s best young shortstop. He hit .310 that year with 213 hits, 33 doubles and 25 stolen bases, earning his first All-Star Game selection and first Gold Glove Award. He hit .322 in 1987, finishing a career-best eighth in the AL Most Valuable Player voting. The Blue Jays won another AL East title in 1989, capping a five-year stretch where Fernández won four Gold Glove Awards and was named to three All-Star Games.

Fernández led the majors with 17 triples in 1990, but the Blue Jays failed to make the playoffs. And after six seasons of high expectations but no postseason success, Gillick – known throughout the game as “Stand Pat” for his patience with his young players – decided to make a blockbuster deal.

The Blue Jays sent Fernández and Fred McGriff to the Padres in exchange for Roberto Alomar and Joe Carter on Dec. 5, 1990, rocking the baseball world. For Gillick, it meant parting with a franchise cornerstone – Fernández – who had come to symbolize the team’s commitment to player development.

“We tried to win with that group and we should have won and we didn’t,” Gillick told writer Tracy Ringolsby. “So it is time for a change.”

Gillick proved to be right when the Blue Jays – led by Alomar and Carter – won back-to-back World Series titles in 1992 and 1993. But at the time of the trade, many thought the Padres – who by getting Fernández had acquired one of the game’s best all-around shortstops – won the deal.

Fernández spent two productive seasons in San Diego, hitting .274 with an All-Star Game selection but failing to help the Padres advance to the postseason. On Oct. 26, 1992, the Padres sent Fernández to the New York Mets in exchange for Raúl Casanova, D.J. Dozier and Wally Whitehurst.

Fernández struggled with the Mets, but found a new beginning when New York traded him back to the Blue Jays on June 11, 1993, in exchange for Darrin Jackson.

“I don’t think you saw me play at my best,” Fernández told Gannett News Service following the trade.

Hitting just .225 in 48 games at the time of the deal, Fernández took over the shortstop role for the Blue Jays and hit .306 with 50 RBI in 94 games, helping Toronto claim its second World Series title. In 12 postseason games in 1993, Fernández hit .326. In the World Series alone, Fernández totaled nine RBI in just six games.

But with his contract expiring following the season, the 31-year-old Fernández found few offers in free agency. On March 8, 1994, he signed a minor league deal with the Reds and earned the job as Cincinnati’s third baseman, hitting .279 with 50 RBI in 104 games in that strike-shortened season.

With the strike still ongoing, Fernández signed a two-year deal with the Yankees on Dec. 15, 1994, agreeing to return to shortstop while prospect Derek Jeter got more seasoning in the minors.

“We didn’t want to rush Jeter and maybe hurt him,” Yankees general manager Gene Michael told The Journal News in White Plains, N.Y., indicating that Jeter might not be ready for full-time duty until 1997.

Fernández hit .245 in 108 games in 1995. But in the spring of 1996, Fernández fractured his elbow, sidelining him for the entire season. Jeter won the AL Rookie of the Year Award while leading the Yankees to the World Series title.

Fernández, however, still had a World Series in his future. He signed with the Indians on Dec. 28, 1996, moving to second base to form a formidable double play combination with shortstop Omar Vizquel. Fernández hit .286 in 120 games in 1997, tying his career-high with 11 home runs.

In the ALCS vs. the Orioles, Fernández got the start at second base in Game 6 when late-season pickup Bip Roberts injured his left thumb in batting practice…on a ball hit by Fernández.

With the game scoreless in the top of the 11th inning, Fernández homered of Armando Benítez to give Cleveland a 1-0 win and the series victory.

“When Tony hit it…I couldn’t believe it,” Roberts told Gannett News Service. “Divine Intervention, there’s no way around it.”

In the World Series against the Marlins, Fernández hit .471 with eight hits and four RBI in five games. His two-run single in the third inning of Game 7 put the Indians in front 2-0.

But in the bottom of the 11th with the score tied at 2, Fernández’s error on Craig Counsell’s grounder turned a potential inning-ending double play into a first-and-third situation. Three batters later, Edgar Rentería singled to center to give the Marlins the world championship.

Fernández joined the Blue Jays for the third time prior to the 1998 season, appearing in 280 games over two seasons as a second baseman and third baseman while hitting .324 and earning his fifth All-Star Game selection in 1999.

Fernández spent the 2000 season with the Seibu Lions of the Japan Pacific League, hitting .327. He returned to the United States in 2001 and hit .293 with the Brewers and the Blue Jays – his fourth stop in Toronto – before retiring at age 39.

In 2,158 big league games, Fernández totaled 2,276 hits, 1,057 runs and 246 stolen bases. He led all AL shortstops in fielding percentage in 1986 and 1989 while leading NL third basemen in the same category in 1994.

His .980 career fielding percentage at shortstop remains in the Top 20 all-time.

Fernández, always open about his religious beliefs while a player, became an ordained minister in retirement but battled polycystic kidney disease for years. He passed away on Feb. 16, 2020, and was laid to rest in his hometown of San Pedro de Macoris.

A bridge between the days of light-hitting shortstops and the generation of larger infielders that followed, Fernández was an inspiration to thousands of his fellow Dominicans.

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Buddy Bell

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Vince Coleman

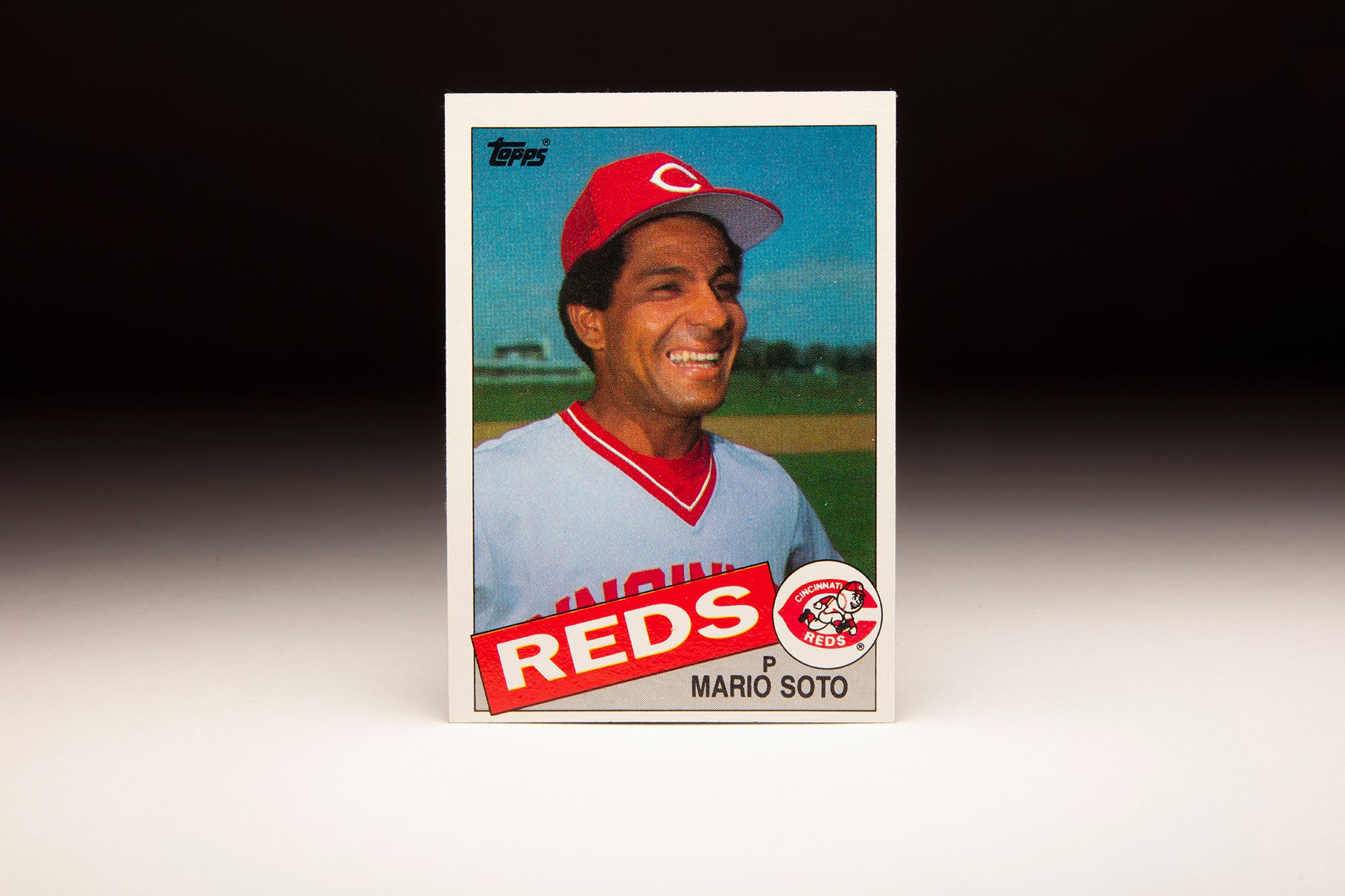

#CardCorner: 1985 Topps Mario Soto

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Buddy Bell

#CardCorner: 1986 Topps Vince Coleman