I just want to get them out, not talk any garbage or tick anybody off. I don’t want anybody wanting to come back and kick my butt the next day.

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1993 Fleer Steve Farr

#CardCorner: 1993 Fleer Steve Farr

Hall of Fame staffers are also baseball fans and love to share their stories. Here is a fan's perspective from Cooperstown.

Yes, Virginia, the New York Yankees did have closers in the days before Mariano Rivera.

Before the great Mariano took over the ninth inning role for Joe Torre in 1997, the Yankees did feature some fairly good relief pitchers who were more than capable of protecting a lead. During their world championship season of 1996, John Wetteland filled the role – and quite effectively. Wetteland was not as good in 1995, when he temporarily lost the closer’s job during the Division Series against the Seattle Mariners, but his tenure in pinstripes generally produced good results.

In 1994, the late Steve Howe shared the closing role with two other relievers, Bob Wickman and Xavier Hernandez. None of the three were as good as Wetteland, but Howe pitched surprisingly well given his longstanding off-the-field problems, while Wickman also fared capably before eventually moving into a fulltime role as a very effective middle inning reliever.

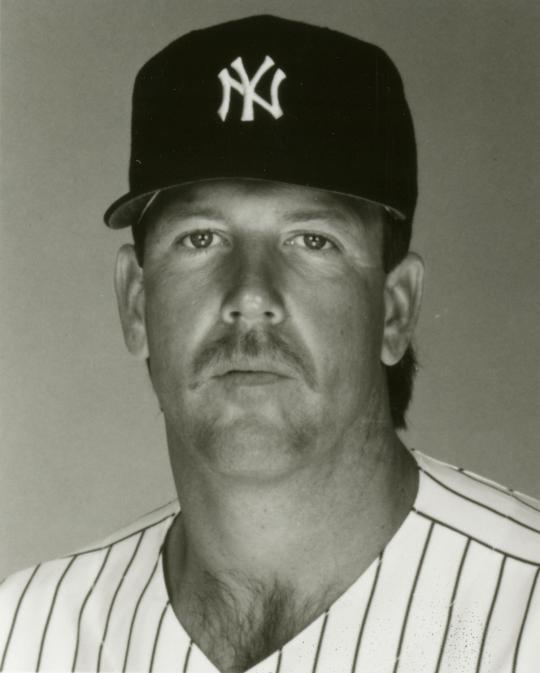

From 1991 to 1993, the Yankees used a now forgotten right-handed reliever as their closer. His name is rarely spoken these days; it’s a name that younger Yankees fans might not be familiar with. He had the misfortune of pitching for the franchise during a down time, just before the latest dynasty, also known as the Joe Torre years, arrived in full force. Yet, for two years, this man pitched exceedingly well as the Yankees’ primary relief ace. During that time, he gained the respect of this writer, to the point that he became one of my favorite Yankees. It’s long past due to put pen to paper in offering some praise for “The Burglar,” Steve Farr.

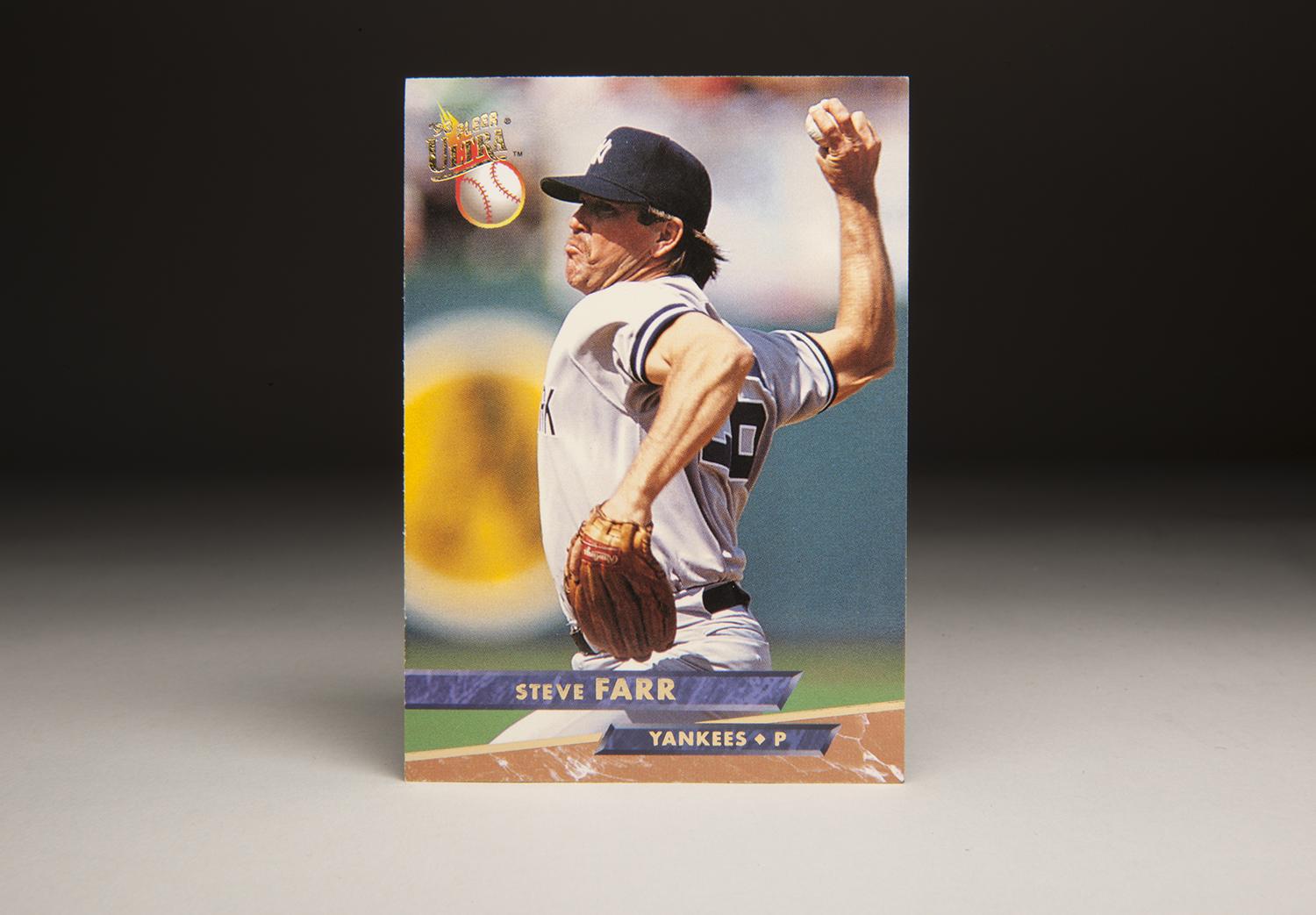

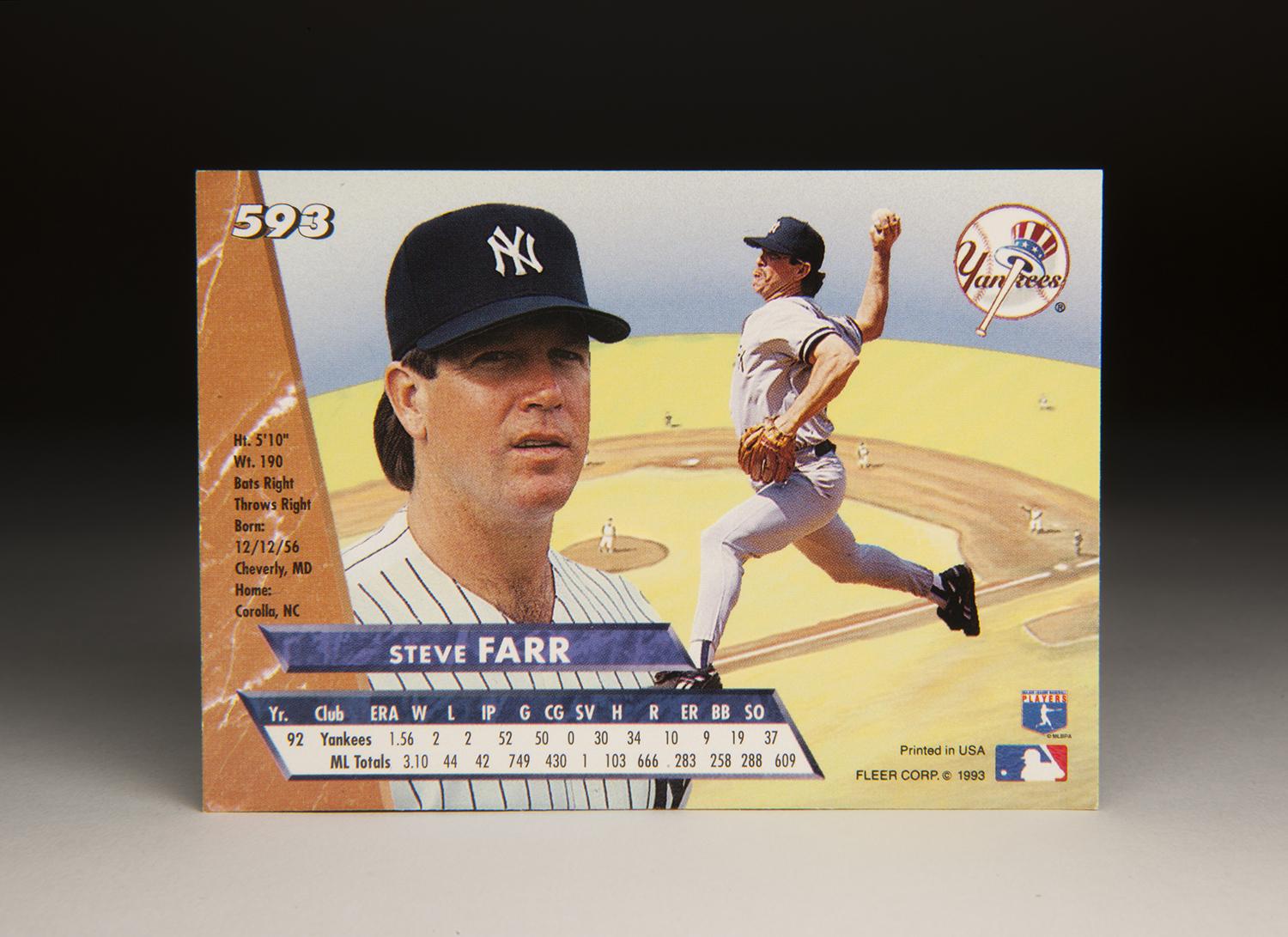

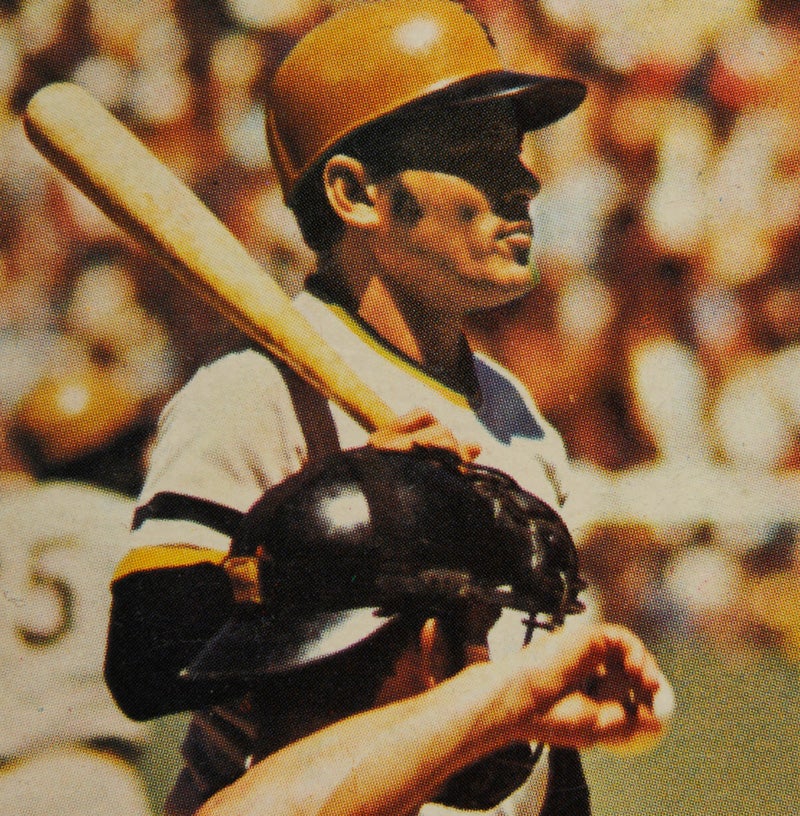

Although he pitched for only three seasons in New York, Farr appeared on a few baseball cards as a member of the Yankees. Well, he appeared on more than a few given how many card companies were making cards in the early 1990s. (Let’s see, there was Fleer, Donruss, Upper Deck, Leaf, Pinnacle, Collector’s Choice, Cracker Jack, and Topps, among others.) Amidst all of the choices, I believe the best card of Farr is this one, a 1993 Fleer Ultra card.

Like all of the Fleer Ultras, the card has no defining border, but rather the postcard look that came into vogue in the 1990s. It also features crisp photography and colorful graphics, including gold-plated lettering.

The Farr card is an excellent close-up action shot, showing the upper half of the veteran right-hander’s body as he delivers a pitch in a road game. The photography is crystal clear, so sharp that we can see the muscles tensing on both his left and right arms, along with the two-fingered grip on his fastball.

Beyond the details on his arms and his pitching hand, we can also see the expression on Farr’s face, which is full of the strain that comes with throwing pitches in a major league game. This is just the way that I remember Farr: An absolute gamer who always pitched to his fullest effort. Whether Farr was able to protect a lead or not, he always gave Yankee fans the impressions that he had given it his all. It was just another reason to like Steve Farr.

Farr’s road to New York was one of complexity, not to mention many fits and starts. It was a professional career that began way back in the Bicentennial year of 1976. Undrafted by the 24 major league teams, Farr settled for signing a free agent contract with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Starting out his career with Niagara Falls of the NY-Penn League, he would spend the next seven and a half seasons plotting a bumpy course that included stops at just about every affiliate in the Pirates’ system.

Farr didn’t make it to Triple-A until 1981, and then pitched so poorly at that level that the Pirates backed him down to Double-A Buffalo the following summer. For the most part, Farr’s minor league record was spotty. To complicate matters, he was only 5-foot-10 and lacked a bigtime fastball that scouts prefer to see in minor league prospects. Short, soft-tossing right-handers are not usually in demand by major league teams, a fact of life that Farr came to realize.

By 1983, Farr’s stay in the Pittsburgh farm system had run its course. In the middle of the season, the Bucs dealt him to the Cleveland Indians for minor league catcher John Malkin. The Indians assigned Farr to Double-A and saw him pitch brilliantly for their affiliate at Buffalo. Putting up an ERA of 1.61, Farr won 13 of 14 decisions. Bumped up to Triple-A Maine the following spring, Farr continued to pitch well and forced the Indians to take a closer look. On May 16, 1984, eight years after signing his first pro contract, Farr finally made his major league debut.

Farr did not exactly make himself a Rookie of the Year candidate. Splitting his time between starting and relieving, he posted an ERA of 4.58. He won three games and lost 11. Granted, the Indians did not have a good team in 1984, but no pitcher wants a winning percentage of .214 at season’s end. To put it mildly, Farr’s long awaited rookie season had gone miserably.

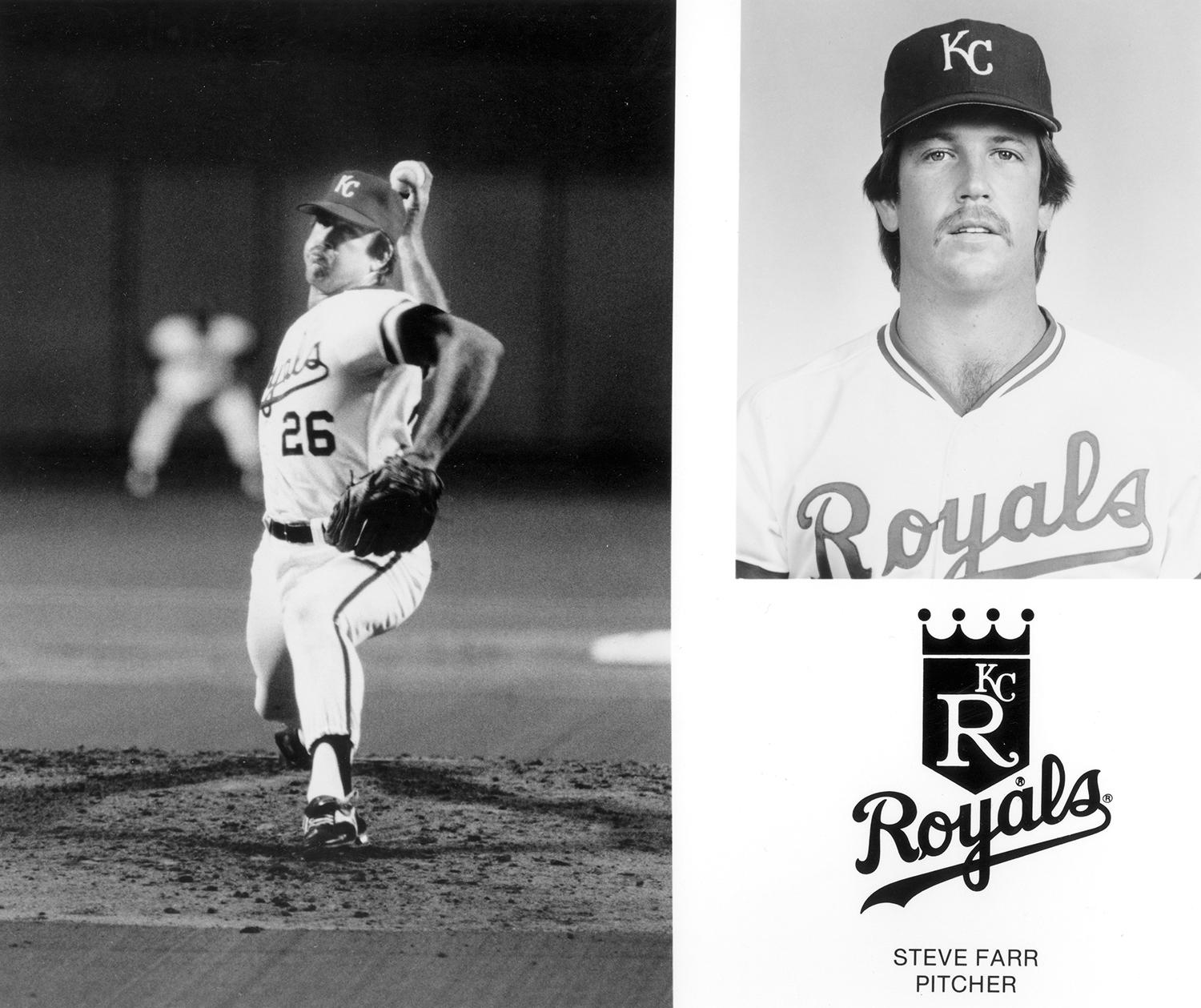

The Indians brought Farr back for Spring Training in 1985, but didn’t like what they saw of the finesse right-hander. On March 31, just before the start of the regular season, the Indians released Farr. Now 28 years old, he remained out of work for a month and a half, his career at the crossroads. In May, one team expressed interest. The Kansas City Royals offered him a minor league contract. Farr took the deal.

Continuing to use Farr as a starter, the Royals watched as the journeyman thrived at Triple-A Omaha. By August, the Royals were ready to move him up.

Royals manager Dick Howser placed Farr in the bullpen, using him in a middle and long relief role. Farr struggled with his control, but otherwise pitched efficiently, striking out a batter per inning and lowering his ERA to 3.11. By season’s end, Farr had become the Royals’ the most effective set-up reliever in front of All-Star closer Dan Quisenberry.

Farr’s arrival as a consistent reliever coincided with the Royals’ pennant-winning run. Farr made two appearances in the Championship Series against Toronto, pitching effectively while picking up a win. Howser chose not to use Farr in the World Series, but that didn’t stop the well-traveled right-hander from earning a World Series ring.

Farr and Quisenberry formed one of the best relief tandems in the game. Farr remained in the set-up role for the next two seasons; he pitched well in 1986, but saw his ERA rise above 4.00 in 1987. Then came an opportunity. Early in 1988, the Royals traded Quisenberry to the St. Louis Cardinals. That created an opening for a new closer. The Royals tapped on Farr’s right shoulder.

Now 31, Farr delivered in a way that must have shocked the talent evaluators in Pittsburgh and Cleveland. Emerging as a workhorse for Kansas City, he appeared in 62 games, logged 82 innings, and saved 20 games. He wasn’t quite Quisenberry, but he was now an above-average closer on a respectable Royals team.

In filling his role as closer, Farr refused to rely on the demonstrative antics that became trademarks of other high-statured relievers. He didn’t stomp around the mound, or fire imaginary arrows into the air. “I don’t like guys like that,” Farr would say several years later in an interview with Jack Curry of the New York Times. “Nine years in the minors taught me enough about being humble.”

Farr also felt that any kind of on-field demonstration might serve as unnecessary fuel to the opposing hitter. “I just want to get them out, not talk any garbage or tick anybody off,” Farr said. “I don’t want anybody wanting to come back and kick my butt the next day.”

Despite his humility, Farr’s pitching took a downturn in 1989. He lost the closer’s role to young right-hander Jeff Montgomery. With Montgomery now entrenched in the late innings, manager John Wathan decided to use Farr in a kind of super-utility role in 1990, pitching him as a set-up man, long reliever, and spot starter.

Farr’s season debut did not go well. He surrendered a mammoth game-tying, three-run home run to Baltimore’s Sam Horn, leading to a crushing loss on Opening Day. It seemed like the struggles of 1989 would carry over to the new season.

Farr’s outing on Opening Day turned out to be an aberration. He would become the most valuable pitcher on Wathan’s staff, logging a career-high 120 innings, winning 13 games, and sporting a 1.98 ERA. Although he finished the season with exactly one save, his performance ranked as the best of his career. Some observers felt that Farr should have received some support for the American League Cy Young Award, but overlooked as always, he did not pick up a single vote.

One of the benefits to his season was the timing. The 1990 season marked Farr’s “walk” year. He was now a free agent, able to take his services to the highest bidder. As a small market team, the Royals tended not to spend much on free agents. Farr received several offers, before ultimately signing with the Yankees. He picked up a three-year deal worth over $6 million, a far cry from his days earning minimum wage playing in the minor leagues.

The Yankees, concerned that they would lose Dave Righetti to free agency, brought in Farr as a hedge against the loss of their established closer. When Righetti signed with San Francisco, Farr became the new Yankees’ relief ace. In his first year with the Bombers, Farr outpitched Righetti. Farr struck out 60 batters in 70 innings, walked only 20, and pitched to a 2.19 ERA. With the Yankees in the midst of a dismal season, there weren’t many opportunities for saves, but Farr came up with 23, rarely blowing games in the eighth or ninth inning.

Unlike many closers who rely on high-octane fastballs, Farr featured a different style. He led with his curveball, at times a devastating pitch. He also threw a decent fastball, one that he was not afraid to use in brushing back batters who became too aggressive. Perhaps most importantly, he had pinpoint control, seemingly able to dot the edges of the strike zone at will.

Once again employing that repertoire, Farr pitched even better in 1992. He lowered his ERA to 1.56 and saved 30 games. He became a ninth inning lock, drawing praise from the media for his unflappable nature and his gritty determination, which was evident both on the mound and in the clubhouse. I remember listening to one of the Yankees games on the radio and hearing John Sterling describe Farr as having “the guts of a burglar.” That line stuck with me. A burglar. For me, that became Farr’s nickname: “The Burglar.” No one else caught onto it; it was my own pet name for one of my new favorite Yankees. Steve Farr was The Burglar – at least in my mind.

Another nickname caught on more popularly with Farr. He became known to teammates and the media as “The Beast,” a testament to the tenacity that he showed when pitching in critical game situations. Farr took his job so seriously, showed so much intensity during a typical game, that it became difficult for him to relax once the game had ended. “I’m wired for two hours after every game I pitch,” Farr told the New York Times.

I loved Farr’s attitude. If he blew the game, he offered no excuses, just carried the blame himself. The consummate gamer, he took the ball whenever manager Buck Showalter asked him to. Farr’s attitude seemed to be: “Give me the ball, and I’ll give you everything I’ve got.” He did that 50 times that summer, never wavering, no matter how much pressure the game situation created.

Even as Farr struggled with bone chips in his elbow during his final season with the Yankees, he retained that same gritty attitude. That’s why I felt bad when the Yankees did not re-sign him for the 1994 season. Even if he could no longer close games, it would have been nice to see him wearing Yankee pinstripes while pitching long relief. Instead, the Yankees took a pass, allowing him to sign with the Cleveland Indians, but he wasn’t the same after undergoing surgery to remove the bone chips. He struggled in Cleveland and then in Boston, finishing his career with 11 forgettable appearances out of the Red Sox’ bullpen.

Farr is out of Organized Baseball now. He lives in the Outer Banks, a group of barrier islands off the coast of North Carolina, where he built his own home and owns his own trucking company. His only connection to baseball remains through the Outer Banks Babe Ruth League, where he lends his expertise to youngsters as a coach. That’s where he teaches baseball – the old school way.

No one in the media covering the Yankees today talks about Farr any more. That’s too bad, because Farr was a good one. All these years later, I hope that Steve Farr realizes at least a few Yankee fans have not forgotten about the good work of The Burglar.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

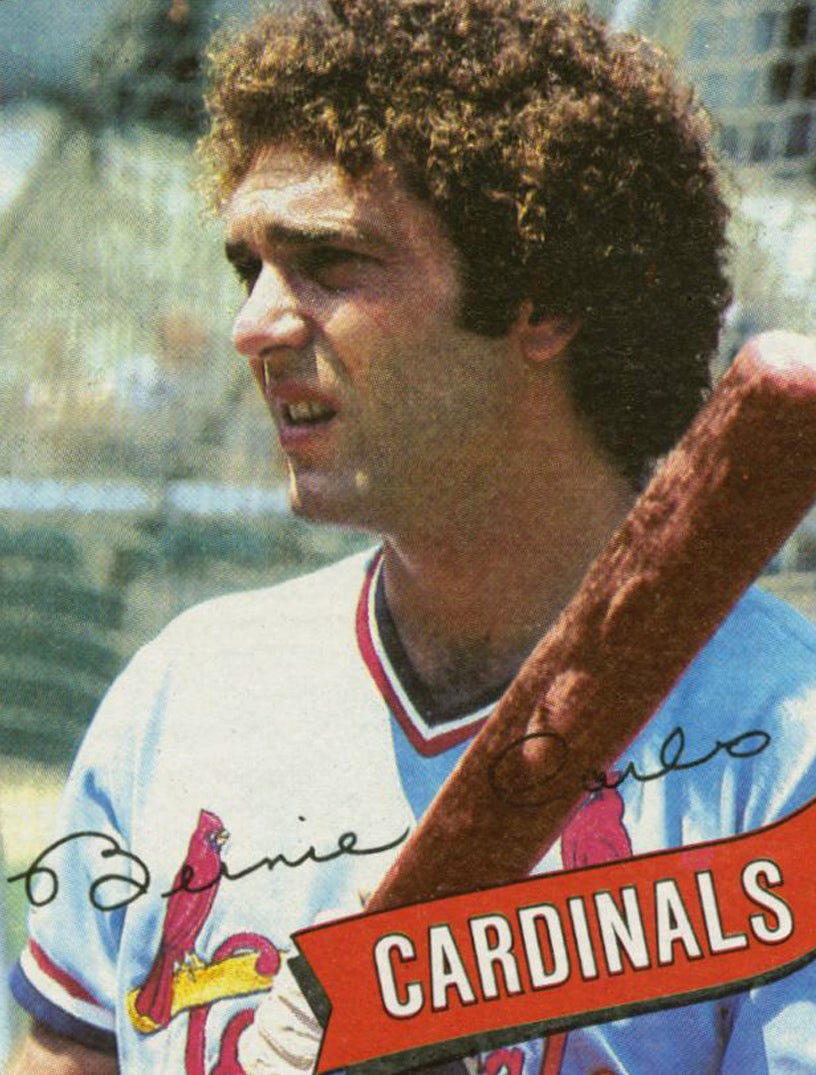

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills