- Home

- Our Stories

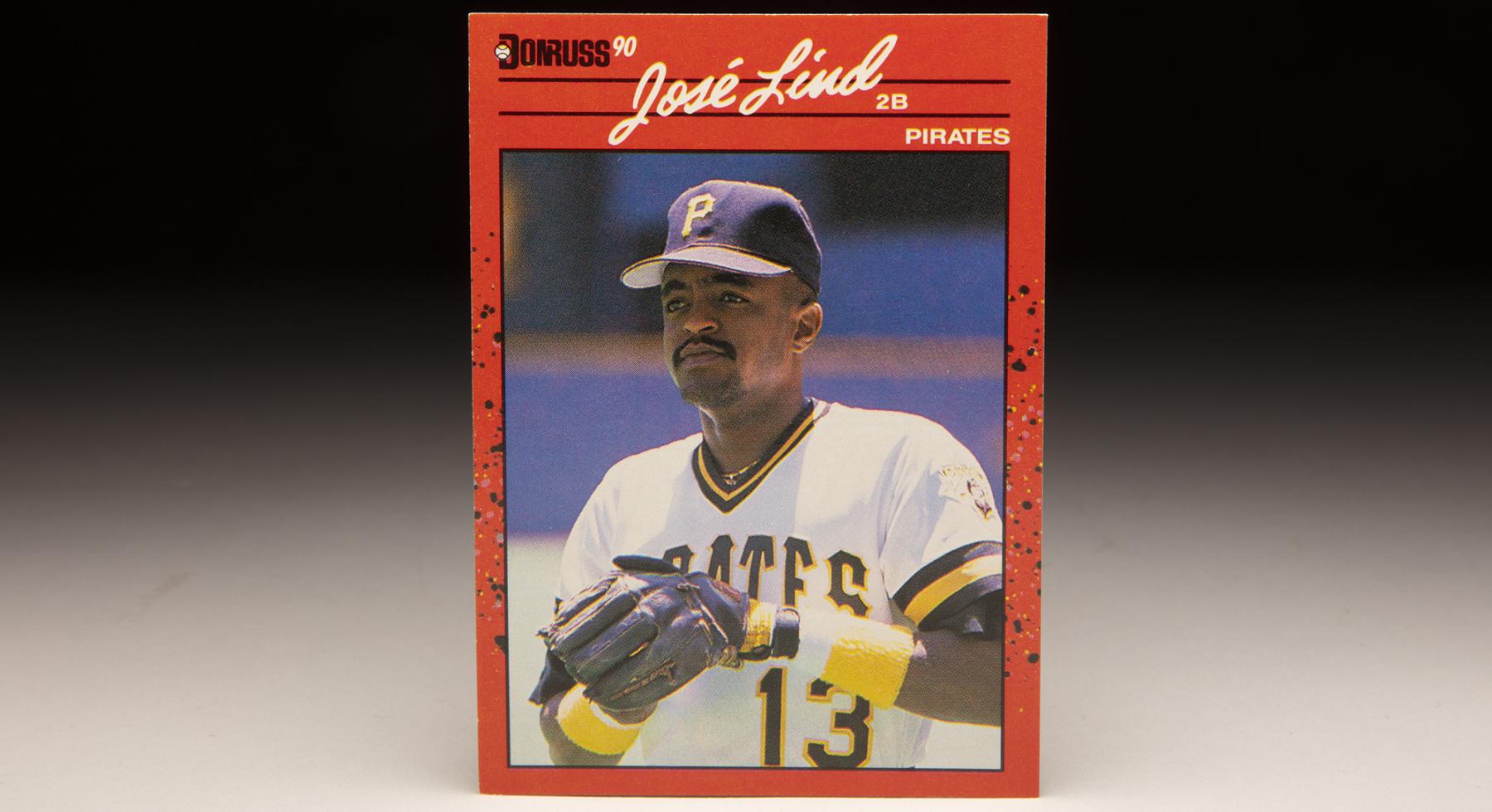

- #CardCorner: 1990 Donruss José Lind

#CardCorner: 1990 Donruss José Lind

With Terry Pendleton on second base and no outs in the bottom of the ninth inning, the Pittsburgh Pirates clung to a 2-0 lead over the Atlanta Braves in Game 7 of the 1992 National League Championship Series.

Pirates ace Doug Drabek, who had baffled the Braves for eight innings, now faced David Justice. On an 0-1 curveball, Justice grounded to the right of Pirates second baseman José Lind, who took three steps before reaching across his body to field the ball.

As one of the best fielding second basemen in the big leagues, Lind had made this play hundreds of times. But on this occasion, the ball slid under his glove for an error – allowing Justice to reach safely and Pendleton to advance to third.

Five batters later, Francisco Cabrera’s single scored Justice and Sid Bream to give the Braves a 3-2 and the National League pennant. And Lind would never again play for the Pirates.

It was an unlikely end to a Pittsburgh career that saw Lind help the Pirates win three straight National League East titles.

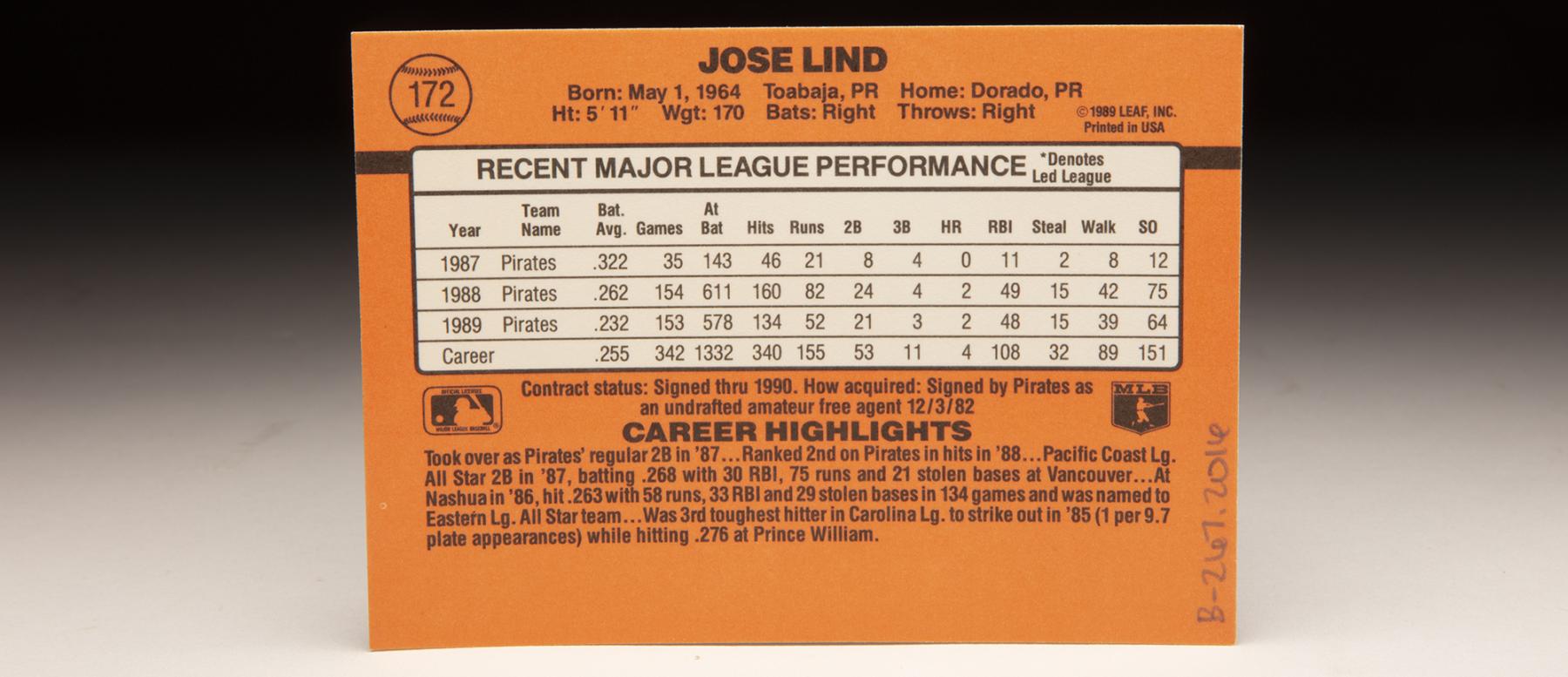

Born May 1, 1964, in Toabaja, Puerto Rico – just to the west of San Juan on the northern side of the island – Lind was a four-sport star in high school, once clearing 6-foot-9½ in the high jump as a 17 year old. The Pirates signed him as an amateur free agent on Dec. 3, 1982, and sent him to the Gulf Coast League in 1983, where he hit .301 in 45 games and displayed his remarkable athleticism.

Lind worked his way through the Pirates’ system the next few years, establishing himself as a prospect by hitting .276 with Class A Prince William in 1985 while making only three errors at second base. In the spring of 1986, new Pirates general manager Syd Thrift explored a trade that would have sent Lind to the Phillies in exchange for infielder Rick Schu – but the Phillies nixed the deal.

That summer, Lind hit .263 with 29 stolen bases for Class A Nashua, leading all Eastern League second basemen with a .982 fielding percentage while also pacing the league in chances, putouts, assists and double plays. He impressed the Pirates enough in Spring Training of 1987 that they assigned him a low number – 13 – and then held off from giving it to any other players when Lind was sent to Triple-A Vancouver for that season.

During Spring Training, Lind became legendary for his leaping ability. He regularly leapt over teammates with only a one or two step start.

“That’s nothing,” Pirates infielder Sammy Khalifa told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “He jumped over my car once.”

In fact, Lind claimed he could jump over some cars from one end to the other.

“I’ve jumped over VWs end-to-end, just for fun,” Lind said.

Lind hoped to leap over Triple-A in 1987, but the Pirates had veteran Johnny Ray at second base. Manager Jim Leyland kept Ray at second during the season as the Pirates continued through a rebuild, and Lind batted .268 and flashed his usual defensive skills at Vancouver.

When Lind was summoned to the big leagues on Aug. 27, the Pirates gave Lind back his No. 13. Two days later, Pittsburgh traded Ray to the Angels for two prospects.

“You can only play one player at a position at a time, and we were going to play José Lind,” Thrift told the Associated Press. “We know he’s one of the best fielders in the major leagues. We know he’s our best-fielding second baseman since Bill Mazeroski. He can turn the double play like few players can. He had to play.”

Lind made Thrift look good in September, batting .322 in 35 games to end the season while committing just one error in 193 chances and compiling a remarkable 1.4 defensive WAR in a little more than one month of play. No player in history has totaled a defensive WAR of at least 1.4 in a season where they appeared in 40-or-fewer games.

Many observers thought Lind – who quickly was tagged with the nickname “Chico” – was a future batting champion, and some believed he would be a perennial All-Star.

In 1988, Lind had what turned out to be the best offensive season of his nine-year big league career. In 154 games, he hit .262 with 160 hits. 49 RBI, 15 stolen bases and 82 runs scored. Defensively, he finished second in the NL with 473 assists and 333 putouts. But with future Hall of Famer Ryne Sandberg in the middle of a streak of nine straight Gold Glove Awards at second base, Lind was shut out during awards season.

“I’ve never seen a second baseman with his range,” Pirates manager Jim Leyland told the Associated Press. “And it would take me a long time to think of anybody who does compare. He has great quickness, but it’s not so much his speed but that he has a real sense of where the ball is going.

“He seems to know where the ball is going before it is hit. And most of the time he’s right.”

Lind showed off his leaping ability to a national television audience during this era when – during pregame interviews on NBC’s Game of the Week – he vaulted over Joe Garagiola, coming up on the future Ford C. Frick Award winner from behind and straddling Garagiola’s head before landing on the artificial turf at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium.

Lind slumped to a .232 batting average and 18 errors in the field during his second full season in 1989, but rebounded in 1990 with a .261 batting average – moving to the eighth spot in the Pirates’ order after batting in the No. 2 hole for 1988 and most of 1989 – while committing just seven errors and leading NL second basemen in putouts with 330.

The Pirates won their first NL East title in 11 seasons that year, and Lind’s RBI triple in Game 1 of the NLCS sparked a Pittsburgh rally that saw the Pirates recover from a 3-0 deficit to defeat the Reds 4-3. Lind’s fifth-inning homer off Tom Browning in Game 2 tied the contest at 1, but Cincinnati won 2-1 and eventually captured the series in six games.

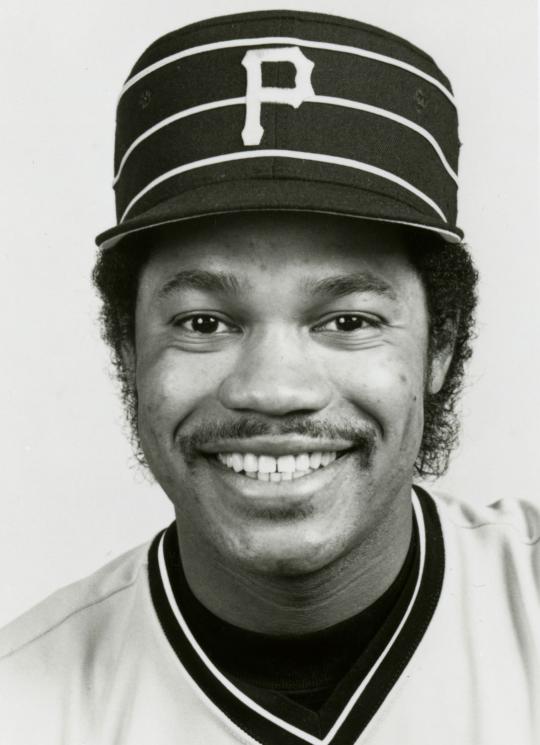

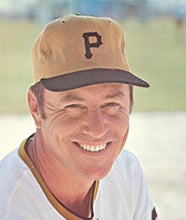

Pirates manager Jim Leyland, shown discussing a play with umpire Charlie Williams, moved José Lind into his starting lineup in 1987. Lind's defense at second base helped Pittsburgh win three straight National League East titles from 1990-92. (National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum)

Lind became eligible for arbitration in 1991 and asked for $950,000, but arbitrator Raymond Goetz sided with the Pirates’ offer of $575,000. Lind turned in a virtual duplicate of his 1990 campaign, hitting .265 and leading NL second basemen with 349 putouts.

The Pirates repeated as NL East champions but this time lost to the Braves in seven games as Lind hit .160.

In the spring of 1992, Lind went back to arbitration and this time won his case, receiving a $2 million salary – the 11th-highest total ever awarded through the process at that time. He proved to be worth the money defensively, snapping Sandberg’s nine-year run by winning the NL Gold Glove Award after leading the league in fielding percentage with a mark of .992.

Offensively, however, Lind’s average dropped to .235, pushing his overall Wins Above Replacement figure to -1.7. Among position players, only Billy Hatcher and Kurt Stillwell had lower marks that season.

In the NLCS, the Pirates met the Braves again – and Lind fared much better than the year before, hitting a solo home run in Game 1 and driving in two runs apiece in Game 2 and Game 6.

But his Game 7 error would be remembered as a play that opened the door to the Braves’ historic rally.

“That was a tough one,” Lind told the Lancaster New Era in 2005. “That one is going to be in my mind forever.”

Following the season – just a week after being named the NL Gold Glove Award winner – Lind was traded to the Royals for pitching prospects Joel Johnston and Dennis Moeller in a move that was widely seen as a salary dump. The Pirates left Lind exposed in the Expansion Draft prior to the trade, but the Rockies and Marlins both passed on him.

“We’ve got to protect as many of our kids as possible,” Pirates general manager Ted Simmons told the Associated Press. “To do that, we have to make some room.

“Inexpensive, young, enthusiastic, aggressive kids, dying to get to the big leagues and busting their butts off – these are the most desirable assets.”

Lind, meanwhile, quickly sold his house in Pittsburgh and went to work learning a new league and adjusting to new teammates.

“I don’t think it will be a problem,” Lind told the Orlando Sentinel about adjusting to new double play partner Greg Gagne. “We’re almost there. It should only take a couple of weeks.”

Lind led all AL second basemen with a .994 fielding percentage in 1993 but continued to struggle at the plate, hitting .248 with a .271 on-base percentage and .288 slugging percentage. He was popular with his teammates though his relationship with the media – which often asked about the NLCS error – soured.

Late in the season, Lind agreed to a two-year, $5.2 million contract extension that would keep him in Kansas City through 1995.

“He keeps everybody loose,” said Royals infielder Curtis Wilkerson, who played with Lind in Pittsburgh.

Lind hit .269 in 85 games during the strike-interrupted 1994 season but battled injuries and lost playing time to prospect Terry Shumpert. Then in 1995, Lind walked off the team on June 2 during a time he told the Royals that he was battling depression after his wife filed for divorce. The Royals released Lind on July 13 after he appeared in just 44 games that season, hitting .236.

“He hasn’t handled this well,” Royals general manager Herk Robinson told the Wichita Eagle.

The Angels signed Lind on July 25, but after batting .163 in 15 games he was released on Aug. 31. He would not appear in a big league game again.

On July 26, 1996, Lind was arrested in Leawood, Kan., for assaulting his ex-wife and drug possession. After another brush with the law in 1997 and serving time in jail, Lind resurfaced in 1999 with the Bridgeport Bluefish of the independent Atlantic League. He appeared in games with the Bluefish in four seasons – hitting .301 in 2000 – before being named manager in 2003. He led the team to winning records in 2003 and 2004 before his final season of 2005.

“I have a good time with the kids,” Lind told the New Era. “I’ve always had fun.”

Over nine big league seasons, Lind hit .254 with 935 hits, 145 doubles and 368 runs scored. In a career filled with his share of lows, it was the highs – with his team in the NLCS or in the air leaping over teammates and automobiles – that Lind proudly recalled.

“I am lucky,” Lind told the Associated Press, “that I have ability you cannot teach.”

Craig Muder is the director of communications for the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

Related Hall of Famers

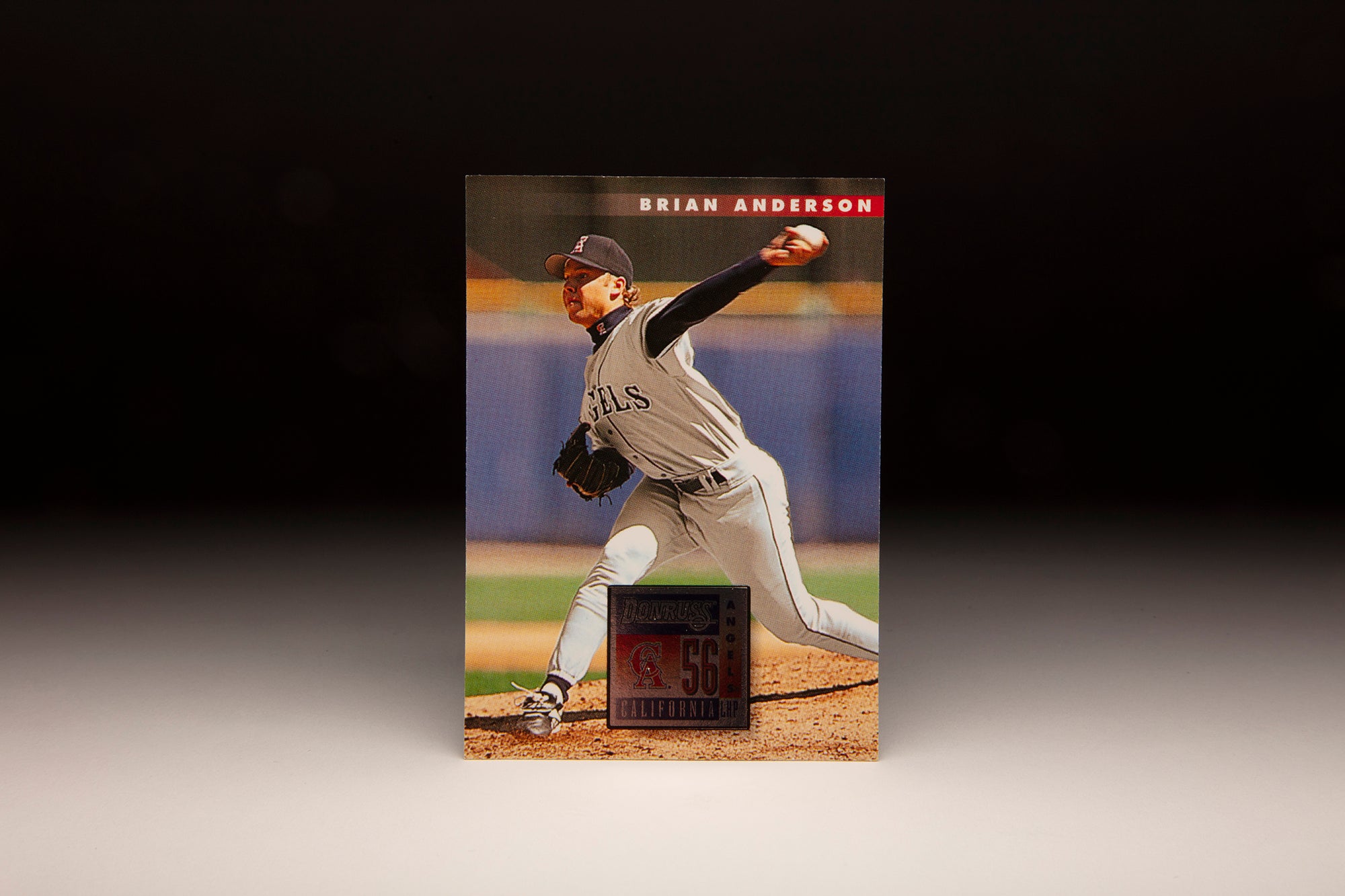

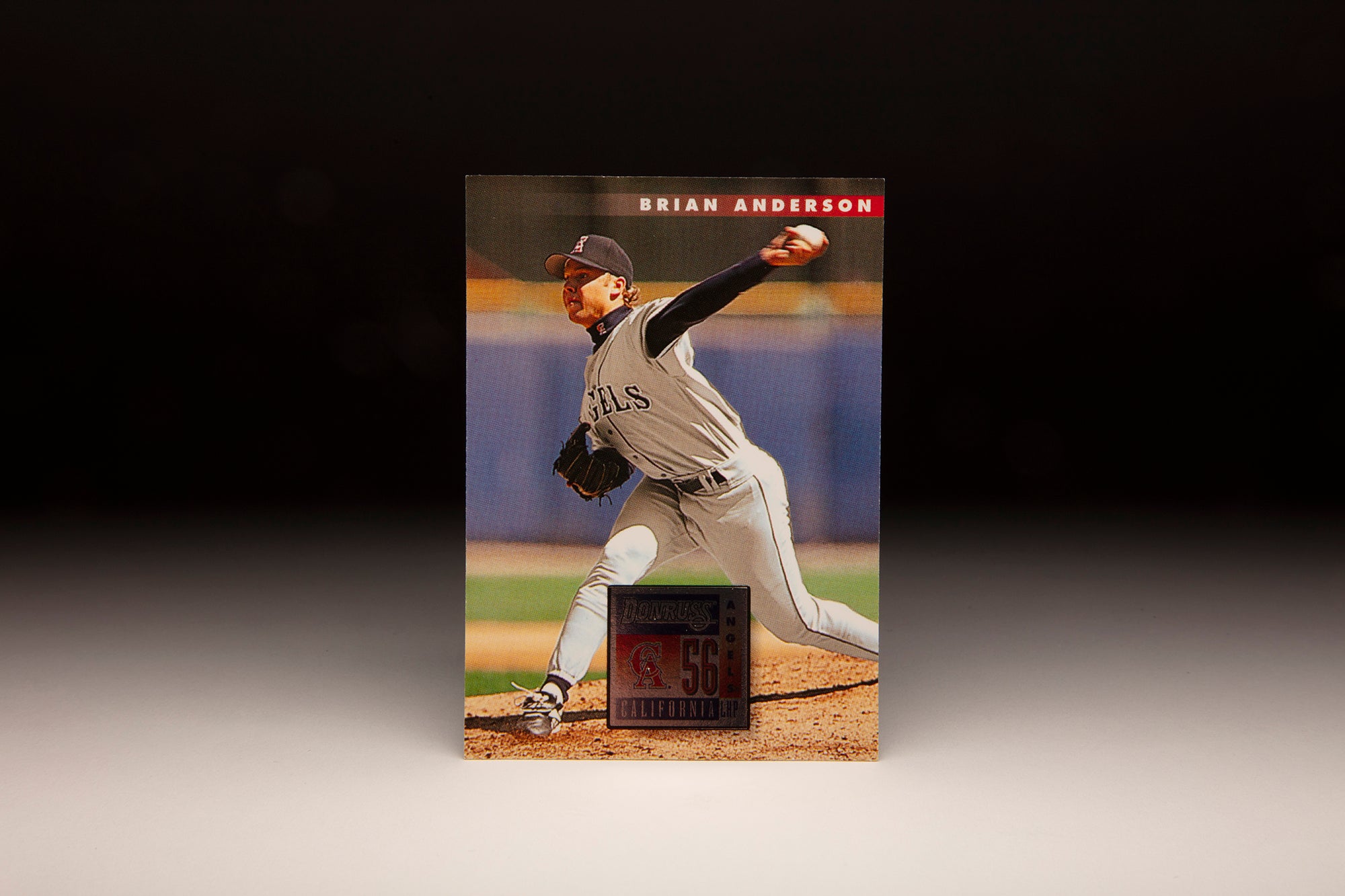

#CardCorner: 1996 Donruss Brian Anderson

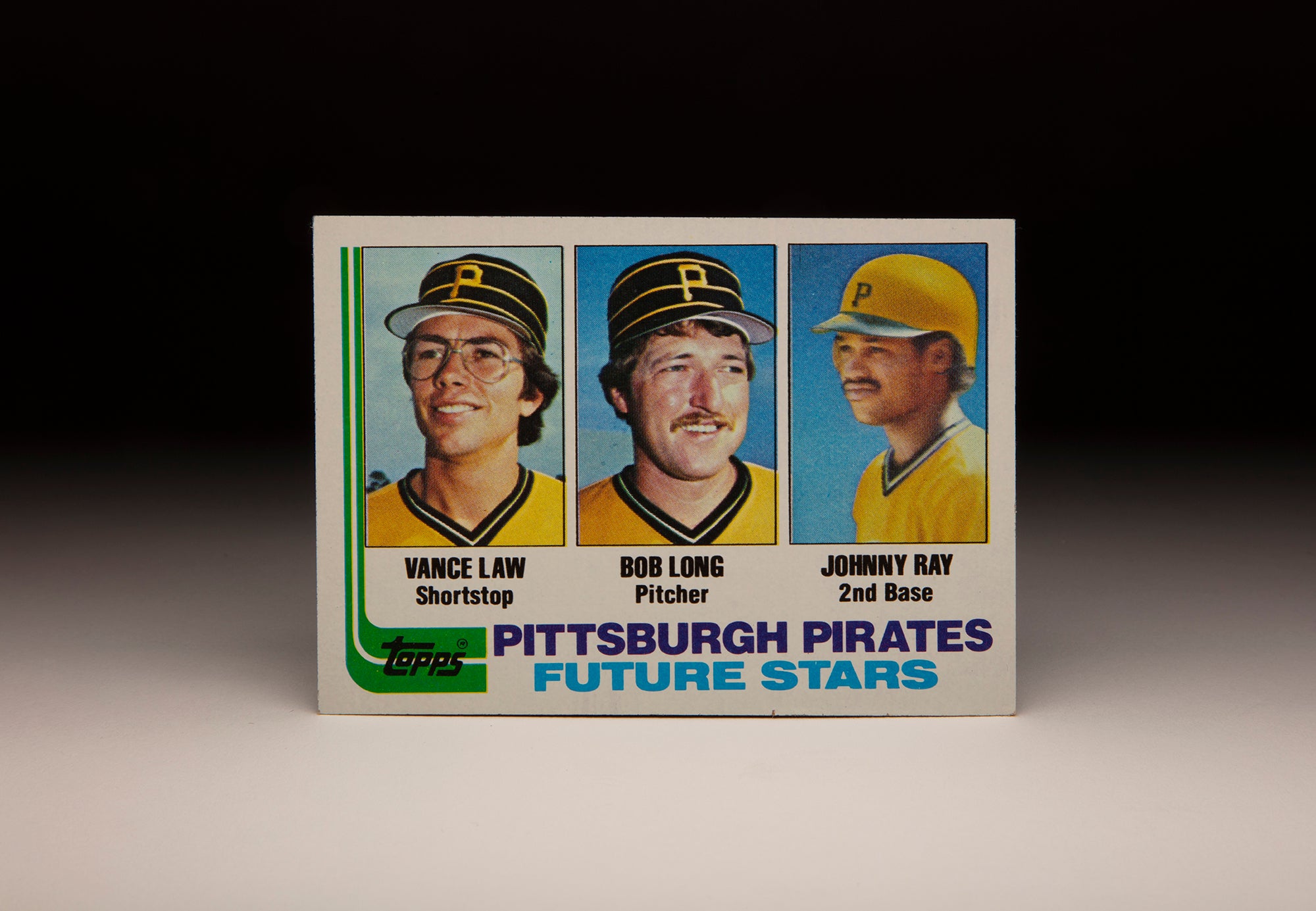

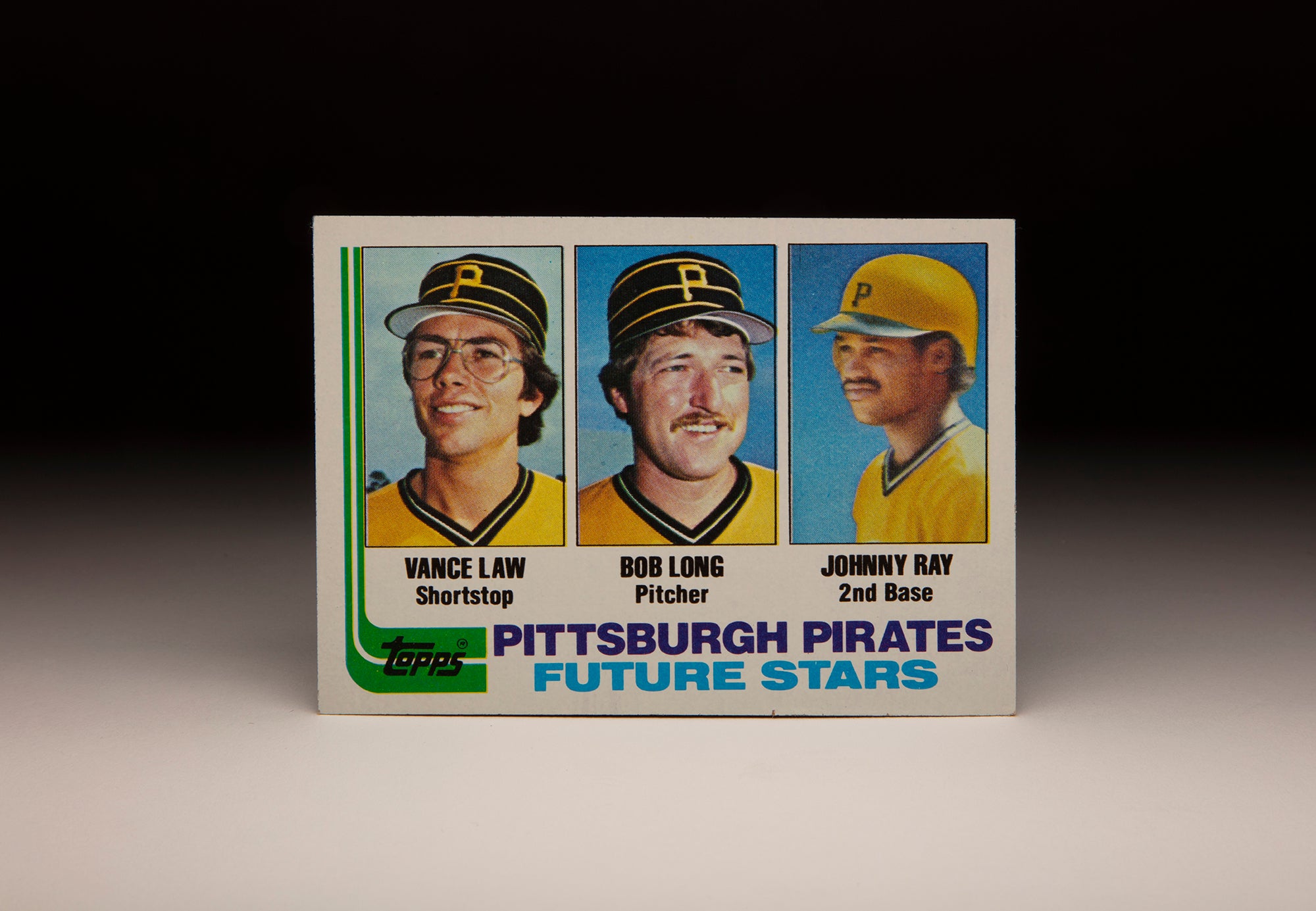

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Johnny Ray

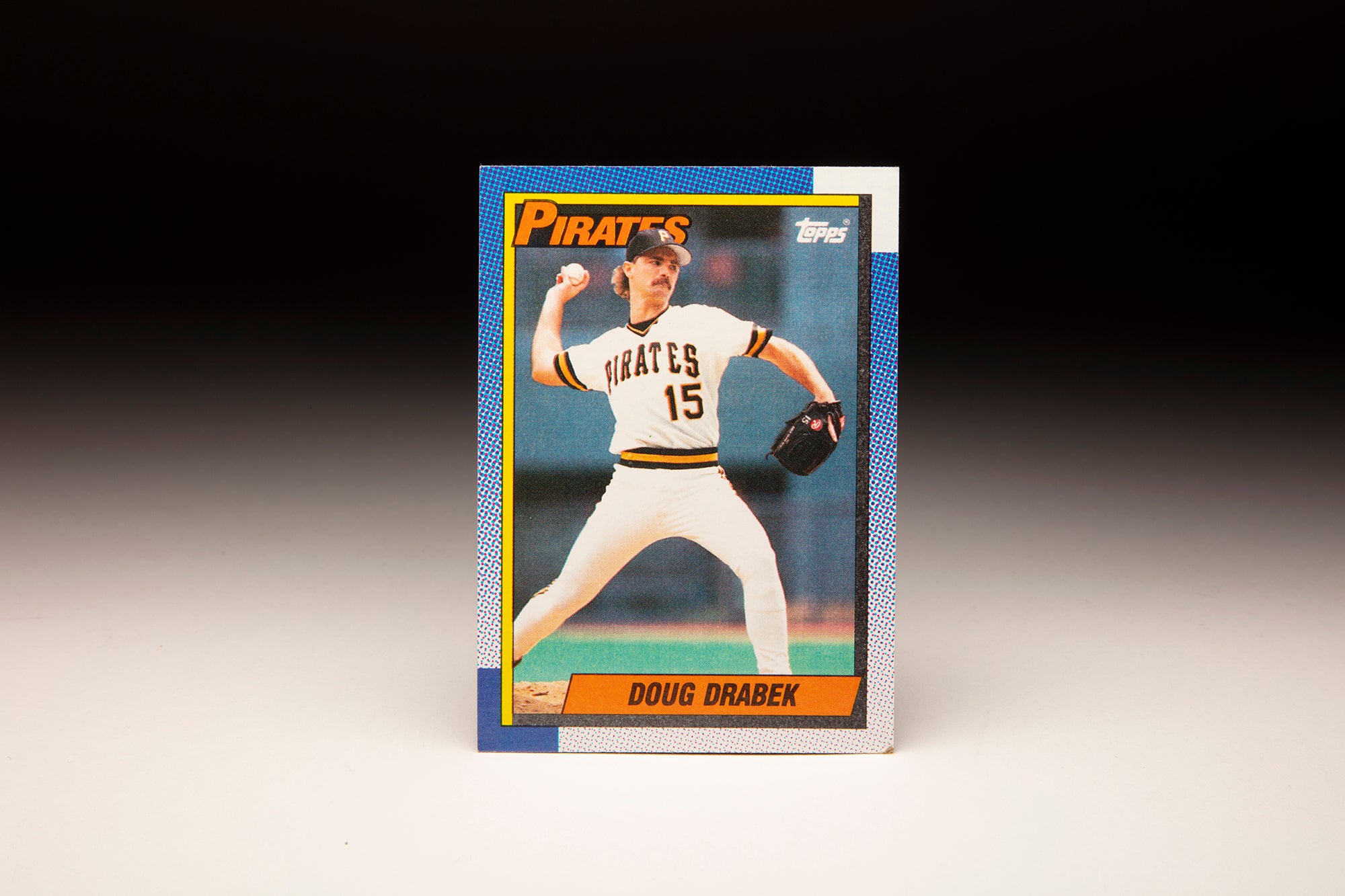

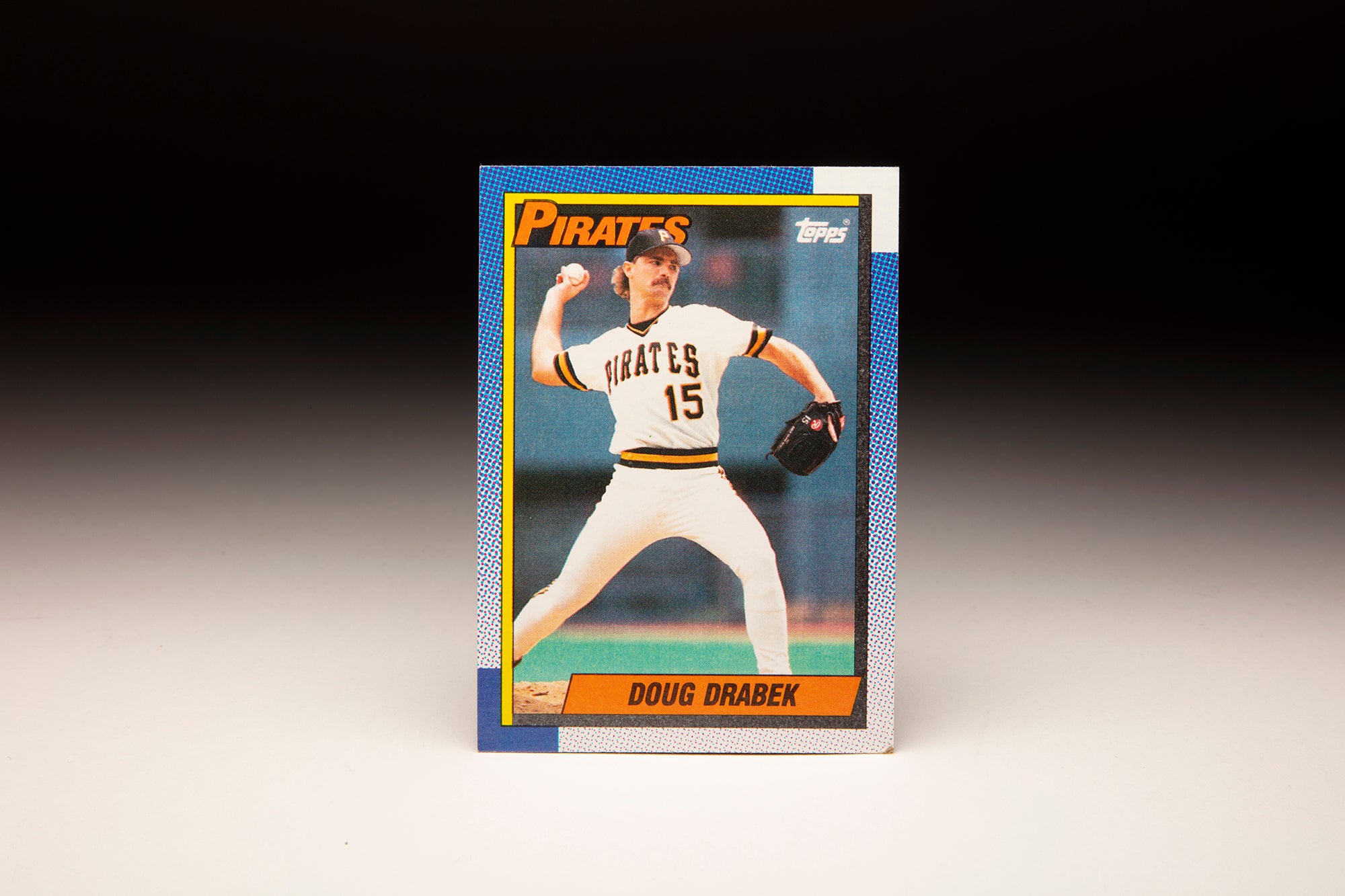

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Doug Drabek

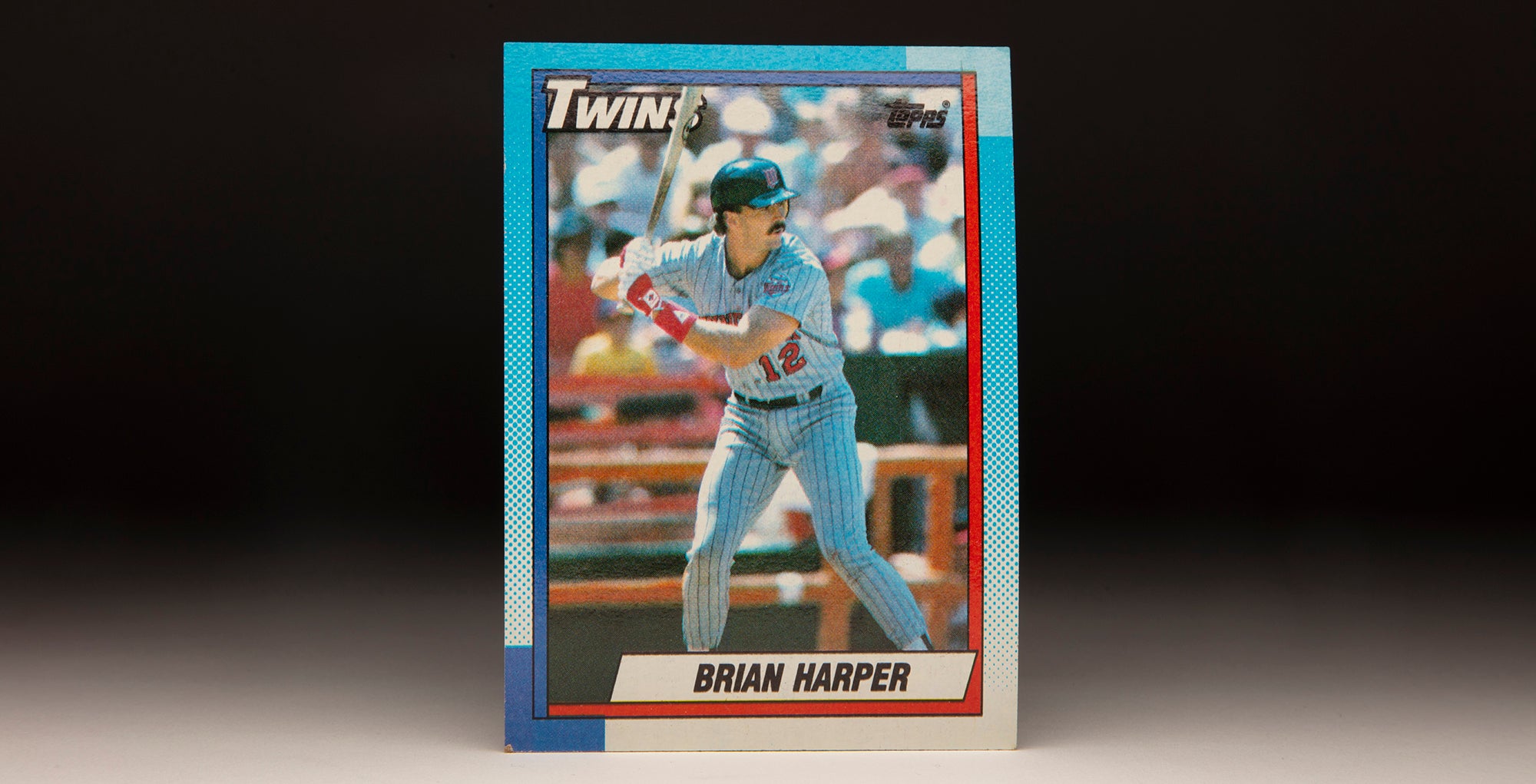

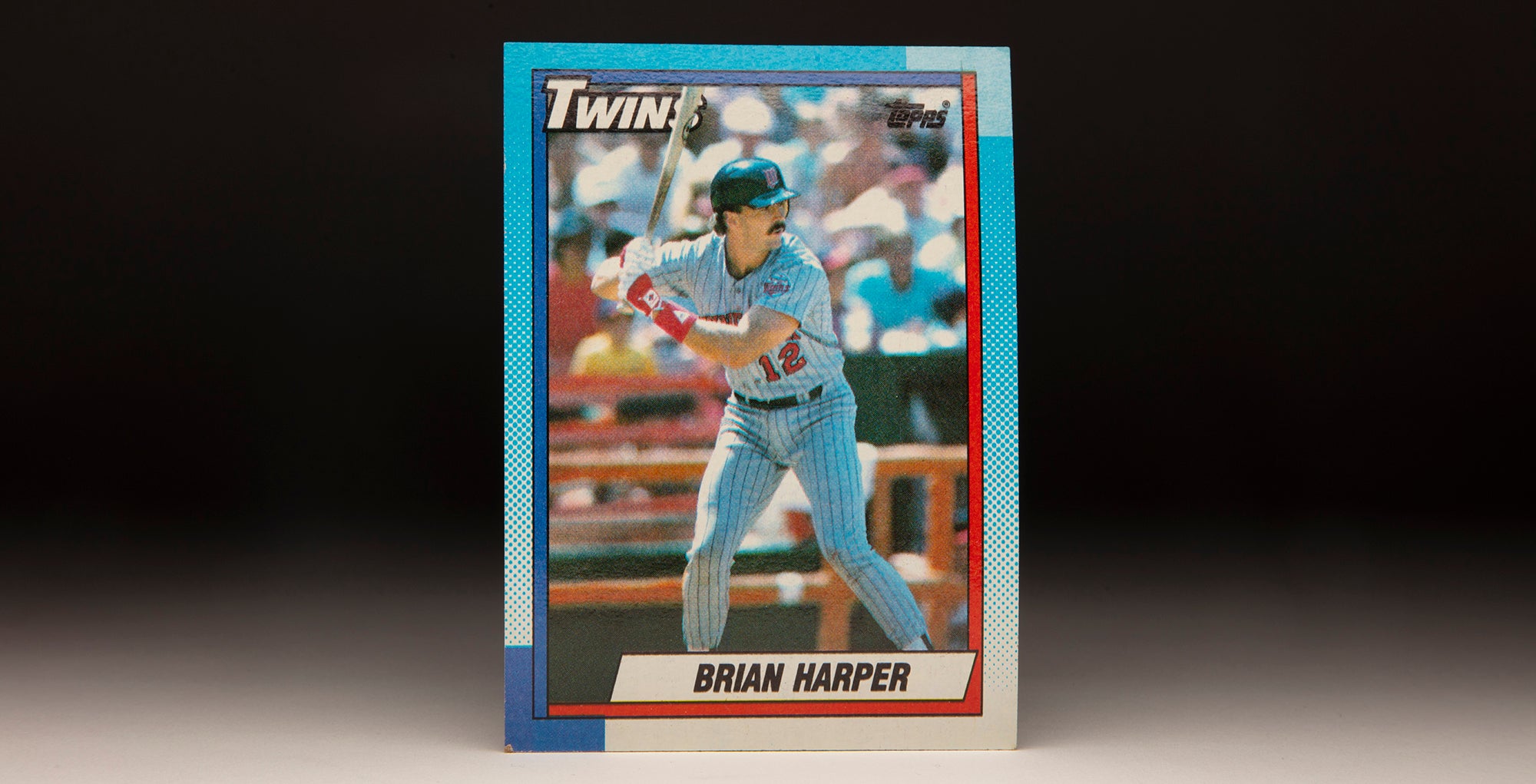

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Brian Harper

#CardCorner: 1996 Donruss Brian Anderson

#CardCorner: 1982 Topps Johnny Ray

#CardCorner: 1990 Topps Doug Drabek