- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1983 Topps Sparky Lyle

#CardCorner: 1983 Topps Sparky Lyle

When a 1980 court decision determined that Topps could no longer continue its monopoly of baseball cards, the judgment turned out to be a boon for card collectors. It paved the way for two other companies, Donruss and Fleer, to start producing full sets of cards in 1981. Collectors and fans now had additional choices when it came to which cards they could purchase.

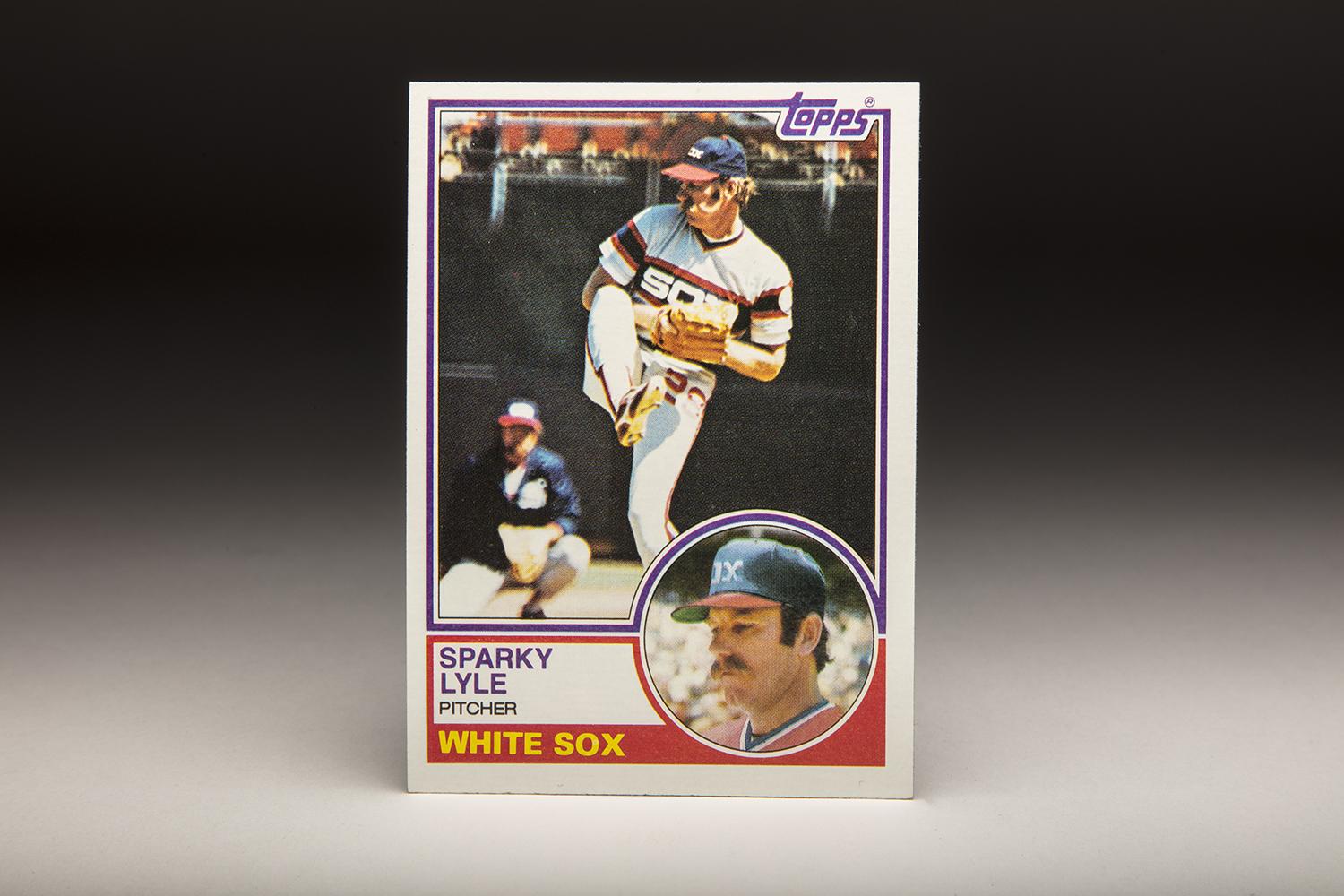

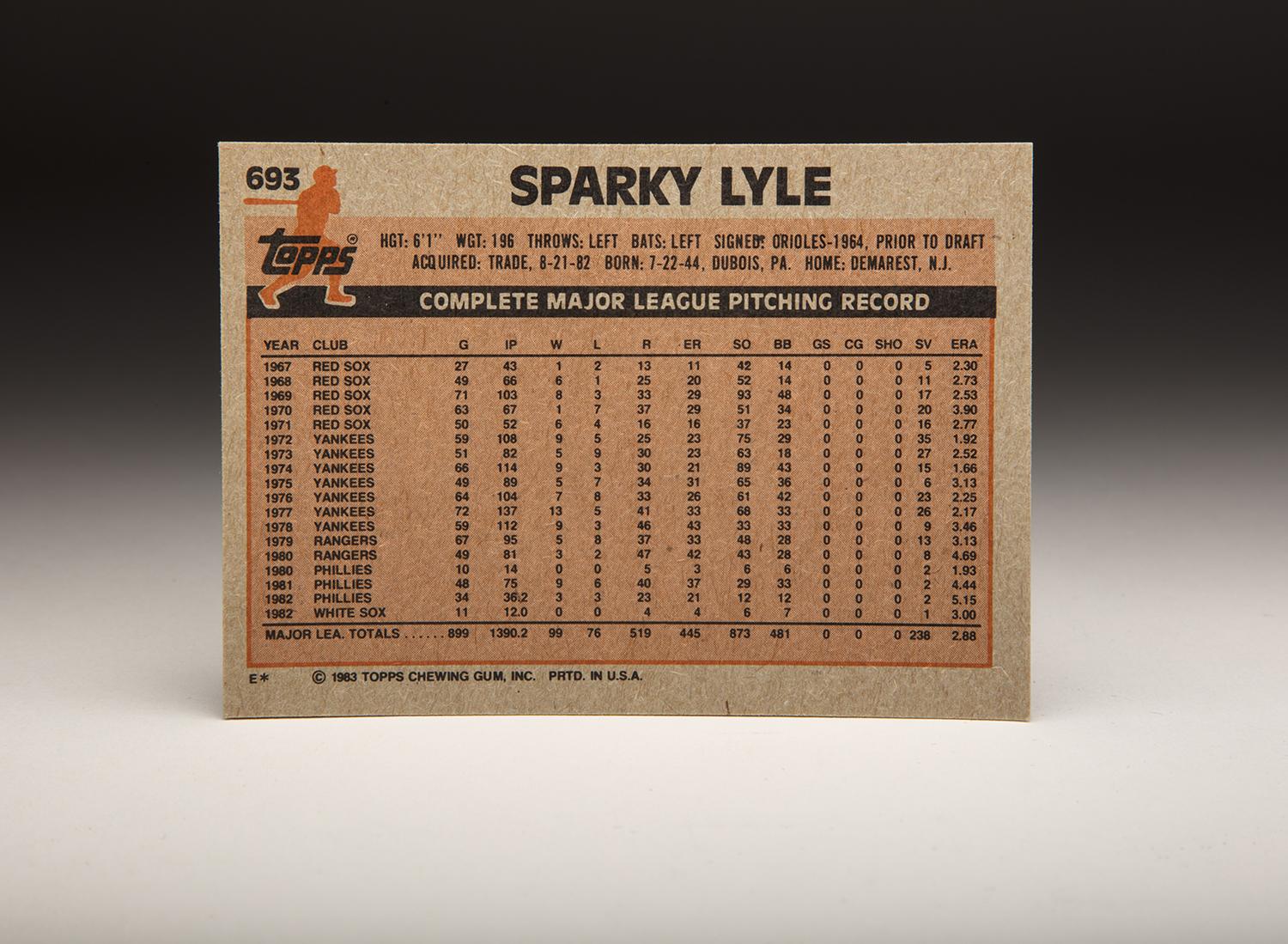

The end of the monopoly also forced Topps to improve its product. Those improvements became evident with the publication of the 1983 set, one of Topps’ best sets of the 1980s. Each player card now featured two photographs on the front: a larger, base photograph, and a smaller, inset photo in the lower left or right-hand corner. Topps also stepped up the number of action shots that it included. In fact, most of the player cards featured action shots as the base photograph, while the smaller photo gave us an up-close look at the player’s face.

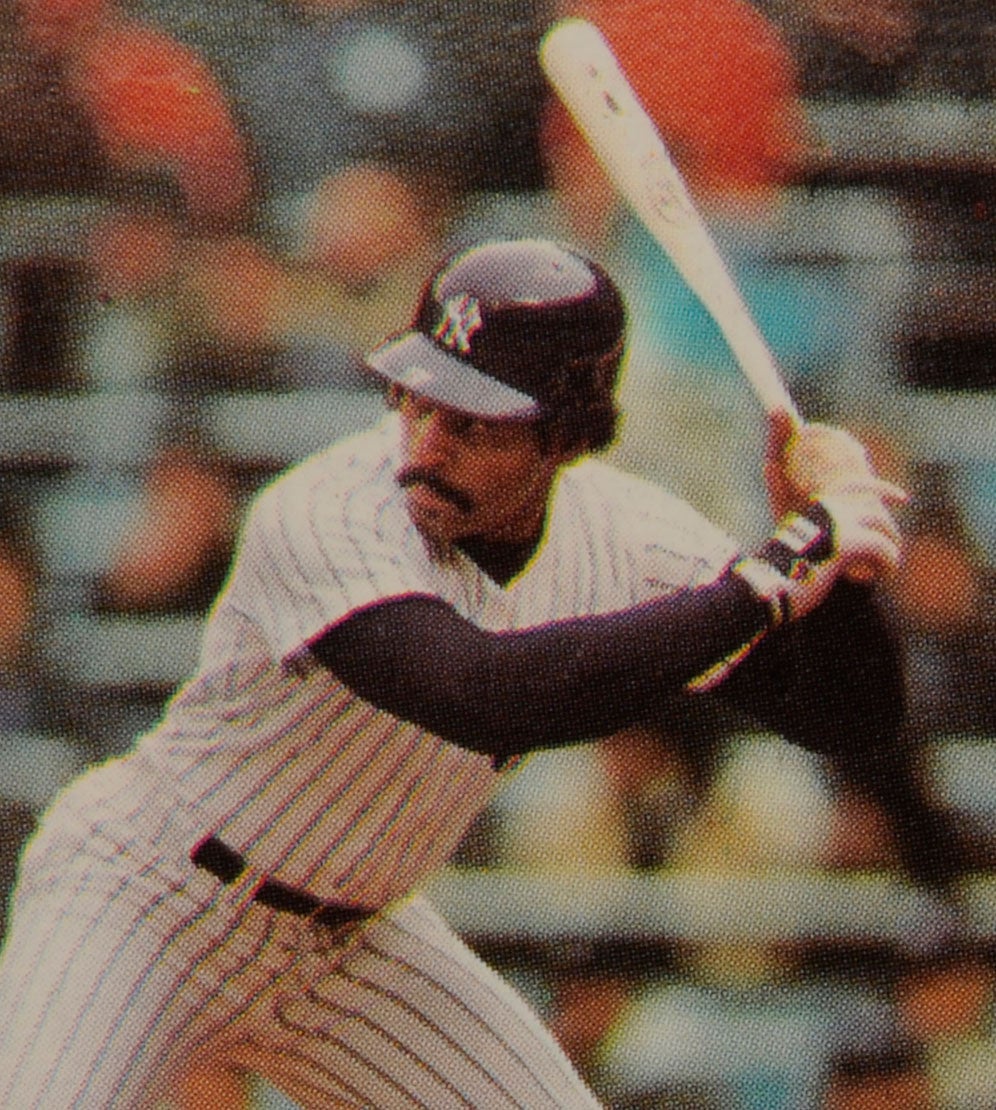

One of my favorites in the ’83 set is Sparky Lyle’s card. It’s intriguing for a couple of reasons. First, it’s an unusual action shot in that it is not taken from an actual game, but rather from a Lyle warm-up session, as he prepares for the possibility of pitching in relief. (The catcher, by the way, is Marc “Booter” Hill, who spent a good part of the 1982 season warming up pitchers in the Sox’s bullpen. Like Lyle, Hill was noted for his practical joking.) I also like the card because it shows Lyle wearing an unfamiliar uniform, that of the Chicago White Sox, the final team for which he pitched.

Hall of Fame Membership

There is no simpler, and more essential, way to demonstrate your support than to sign on as a Museum Member.

The card also gives us a glimpse of Lyle’s distinctive delivery. Notice his high leg kick and how he turns his back completely away from the catcher before releasing the pitch. That means that Lyle somehow has to pick up the target from his catcher, just a tick before releasing the pitch. Given the unusual nature of the pitching motion, it’s amazing that Lyle threw strikes as often as he did.

As baseball fans, we tend to remember Lyle pitching for the New York Yankees. A few older fans might recall Lyle’s early major league days with the rival Boston Red Sox. But how many of us realize that he was originally linked to another team now in the American League East? I certainly didn’t, at least until I looked up Lyle’s entry on his Baseball-Reference.com page. It was actually the Baltimore Orioles, thanks to the efforts of scout George Staller, who signed him as an amateur pitcher in 1964. Lyle spent one season pitching in the lower reaches of the Baltimore farm system, but never again returned to the organization. That’s because the Orioles did not place Lyle on their 40-man roster after the season, thereby making him eligible for the old first-year player draft.

The Red Sox took advantage of the oversight, drafting Lyle that winter and making the critical decision to convert him from starting pitcher to reliever. The Red Sox felt that it was the perfect place for the inexhaustible youngster, who had been nicknamed “Sparky” by his father because of his seemingly unending reserve of energy. Believing that Sparky could better channel his energies pitching frequently out of the bullpen, the Red Sox made the decision that would change the fortunes of the young left-hander’s career.

Lyle struggled with his control in 1965, but would turn the corner in 1966. During Spring Training, he met Ted Williams, who was in Red Sox camp as a preseason instructor. Williams encouraged Lyle to develop and throw a slider, a pitch that the “Splendid Splinter” considered the most difficult for hitters, including himself, to handle. “Ted Williams told me that I’d never make the big leagues unless I came up with a slider,” Lyle recalled in an interview many years later. “I threw the pitch so it would come straight at the batter until it got to within three feet of the plate. Then it would break down.” Taking the advice from the great Williams, Lyle developed and refined what would become one of the most devastating sliders of the 1960s and 70s.

Equipped with his new out pitch, Lyle pitched well as a minor leaguer in 1966 and the first half of 1967. Duly impressed, the Red Sox brought him to Boston in midseason. He became an important part of the Red Sox’ bullpen at just the right time; the Sox were engaged in a frantic pennant race. On a team with so many high-profile players, from Carl Yastrzemski to Reggie Smith to Jim Lonborg, it’s easy to overlook just how important Lyle became during the stretch run; in 27 late-season appearances, he pitched to an ERA of 2.28, struck out 42 batters in 43 games, and saved five games. Lyle’s stunning performance as a rookie reliever helped the Red Sox achieve their “Impossible Dream” of winning the pennant, as they beat out the Chicago White Sox, Detroit Tigers, and Minnesota Twins during a frenzied race. Without Lyle’s second-half efforts, the Red Sox might have fallen short of a World Series berth.

As well as Lyle pitched down the stretch, he also developed soreness in his left arm. That’s why the Red Sox did not include him on their World Series roster. So he watched from the sidelines, as the Sox battled hard, before eventually losing to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven tough games.

Over the next four seasons, Lyle continued to pitch well for the Sox. At first, he shared fireman duties with Lee Stange and Gary Waslewski but eventually took on the bulk of the role as Boston’s bullpen stopper. Lyle’s success made the developments of Spring Training in 1972 all the more surprising. In late March, the Red Sox traded Lyle, sending him to the Yankees for first baseman Danny Cater and a player to be named later (which turned out to be shortstop Mario Guerrero).

So why did the Red Sox make the trade? According to some, the Red Sox felt that Lyle’s fastball had lost velocity over the last season. Former Red Sox pitcher Bill Lee came up with another explanation, saying that Lyle had run afoul of team owner Tom Yawkey. The consummate practical joker, Lyle liked to have fun by sitting down on birthday cakes. Supposedly, Lyle sat on one of Yawkey’s birthday cakes, upsetting the owner. According to Lee, Yawkey demanded that Red Sox general manager Dick O’Connell trade Lyle as soon as possible.

Whatever the actual reason, the trade would become one of the most one-sided transactions of the 1970s. In fact, it would have an impact on future relations between the two teams. Due to that trade, the Red Sox and Yankees, arguably the two fiercest rivals in the game, became reluctant to make trades, the unofficial moratorium continuing for a number of years.

Yankees manager Ralph Houk quickly took a liking to Lyle. “He’s a throwback to the old-time ballplayers,” Houk told the Associated Press in July of 1972. “He likes the game, knows what his job is, and he has that inbred confidence which a ballplayer needs.”

Confident in Lyle himself, Houk turned to the left-hander as his workhorse out of the bullpen. Houk called on Lyle 59 times, allowing him to pile up 107 innings. Using his slider to great effectiveness, while complementing it with an above-average fastball and a fine curve, Lyle justified the confidence of his manager by spinning an ERA of 1.92 and collecting 35 saves, an impressive number at the time and one that helped him qualify for Fireman of the Year honors. Lyle also earned heavy consideration for both the MVP Award (finishing third) and the Cy Young Award (finishing seventh).

Lyle’s entrances in games at Yankee Stadium became a spectacle. Marty Appel, the Yankees’ assistant public relations director at the time, devised the idea of playing “Pomp and Circumstance” over the organ at Yankee Stadium as Lyle made his way toward the infield in the bullpen car. Lyle then stepped out of the car, flung his warmup jacket over his shoulder, and dramatically slammed the door shut.

In 1973, Lyle did not pitch quite as well, but still managed to save 27 games and made the All-Star team. In 1974, Lyle added a mustache to his facial repertoire – the mustache would become a trademark for him – but far more importantly, turned his pitching from merely good to positively brilliant. His ERA checked in at a near spotless 1.66, even though he was used less often in save situations and more often in high-leverage opportunities that helped the Yankees win games. By season’s end, he had piled up 114 innings, an enormous total for a late-inning reliever.

Injuries limited Lyle to 49 appearances in 1975, but he bounced back in both 1976 and ’77, coinciding with the Yankees’ return to postseason glory. He save a combined 49 games over that two-year span, culminating with a Cy Young Award-winning performance in 1977. Logging 137 innings, Lyle completely dominated the end of games. He led the league with 72 appearances, lowered his ERA to 2.17, and won 13 games while pitching exclusively out of Billy Martin’s bullpen. In winning the Cy Young, Lyle made history; no American League pitcher had previously won the award.

As good as his regular season was, Lyle’s value reached a high point in Game 4 of the American League Championship Series. With starter Ed Figueroa knocked out early and Dick Tidrow struggling in an abbreviated relief appearance, Martin turned to Lyle in the fourth inning. Martin would need no other pitchers that afternoon. Over the next five and a third innings, Lyle completely shut down the Kansas City Royals, allowing no runs and only two hits. Lyle maintained a slim lead for the Yankees, on the way to a critical 6-4 win over the Royals. Not only did Lyle stave off elimination for the Yankees, but he also cleared a path for another terrific relief performance in Game 5, as the Yankees took the pennant, three games to two. Lyle would continue his run of brilliance in the World Series, helping the Yankees win their first world championship since 1964.

Not only did Lyle emerge as one of the game’s most dominant relievers with the Yankees, he also compiled a list of practical jokes that would have made him a candidate to join the cast of Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In. Here are just a few examples of Lyle’s handiwork:

*In one of his most famous stunts, Lyle decided to have some fun at the expense of another Yankee pitcher. Somehow, he secured the waterbed that belonged to fellow left-hander Mike Kekich, who apparently carried the bed (free of water) with him on road trips. Lyle took the waterbed, climbed the scoreboard at Milwaukee’s County Stadium, and hung the bed from the scoreboard. As the Yankees played the Brewers that day, fans and players alike watched in amazement as the water bed dangled in the wind.

*As the Yankees flew on one of their charter flights, Lyle targeted team broadcaster Phil Rizzuto, who was known for being particularly squeamish. Rizzuto did not like snakes, or bolts of lightning, or generally anything else that suddenly might cause his heart to race. As Rizzuto slept on the team flight, Lyle snuck up on him while wearing the mask of the Wolf Man, the famed Universal Studios monster who was played by Lon Chaney, Jr. Rizzuto suddenly woke, saw the face of the Wolf Man just inches away, and let out a loud scream. The plane erupted in laughter, as Rizzuto did his best to catch his breath.

*Lyle also pulled pranks at his home base of Yankee Stadium. On one occasion, he arranged to have a funeral home deliver a casket to the clubhouse. Waiting for the opportune moment, Lyle climbed into the casket. As manager Bill Virdon began to speak to his players during a team meeting, the casket started to creak open. Lyle slowly sat upright, looked at Virdon and his teammates, and began delivering his best imitation of Bela Lugosi. “How do you pitch to Brooks Robinson?” Lyle asked cryptically, to the stunned amazement of Virdon and his coaches. It’s believed that this prank earned Lyle his nickname of “The Count.”

*Lyle’s trademark prank became his treatment of birthday cakes. In celebration of a player’s birthday, the Yankees typically arranged for a large birthday cake to be delivered to the ballpark. When Lyle saw the delivery man place the cake on a table, he pulled down his pants, ran over to the cake, jumped in the air, and firmly planted himself on top of the cake. Lyle’s antics left the cake destroyed, and completely inedible. Even Topps paid homage to Lyle and his cake habit. As the back of his 1974 Topps card states, “Sparky enjoys birthday cakes.”

In 1978, Lyle’s mood became less playful, largely because of his diminished role in the Yankees’ bullpen. Even though he had signed a three-year contract in 1977, his role would soon diminish. With the addition of Hall of Famer Goose Gossage and Rawly Eastwick as much heralded free agents, the Yankees relegated Lyle to a set-up role. Lyle felt betrayed; he had won the Cy Young Award in 1977, only to have his fireman role taken away from him. As teammate Graig Nettles would say in 1978: “From Cy Young to sayonara.”

Lyle’s pitching suffered that summer, perhaps the result of being pressed into middle relief. Unhappy, he asked for a trade. The Yankees accommodated him over the winter, sending him and four minor league prospects to the Texas Rangers in a blockbuster deal that brought a young Dave Righetti to the Bronx.

Lyle’s departure from the Bronx did not come without some controversy. As he prepared for his first season in Texas, his new book, The Bronx Zoo, hit bookstores. Co-authored by noted writer Peter Golenbock, the book essentially served as a diary of the winter of 1977 and the entire 1978 season, complete with raucous accounts of behind-the-scenes escapades. The book became a bestseller and received much critical acclaim, especially for its humorous look at the game, but its no-holds-barred approach also irritated some within the Yankee organization, including team owner George Steinbrenner.

On the field, the Rangers expected Lyle to bolster the back end of their bullpen, but he ended up playing second fiddle to Jim Kern, another wintertime acquisition. In Texas, the writers referred to Lyle and Kern as the “Million Dollar Bullpen.” The two shared the fireman role, but Kern’s prolonged effectiveness made him the No. 1 reliever in the pecking order. Much like his final season in New York, Lyle had to settle for a secondary role.

Lyle returned to the Rangers in 1980, but he was less effective than he had been in 1979. In September, the Rangers decided to unload Lyle, sending him to a contending team. Lyle joined the Philadelphia Phillies, pitching well in 10 late-season appearances. Unfortunately, he was not eligible for postseason play, forcing him to watch from the sidelines as the Phillies won their first world championship.

Remaining in Philly for the better part of the next two seasons, Lyle continued to pitch in middle relief. Late in 1982, the Phillies designated Lyle for assignment and then sold him to the White Sox. He finished out the ’82 season in the Windy City, but then drew his release in October. Having already produced a card for Lyle and perhaps figuring that someone else would pick him up, Topps decided to include him in the 1983 set. But Lyle never found a home for 1983. He opted for retirement, making his Topps card out-of-date before the new season even began.

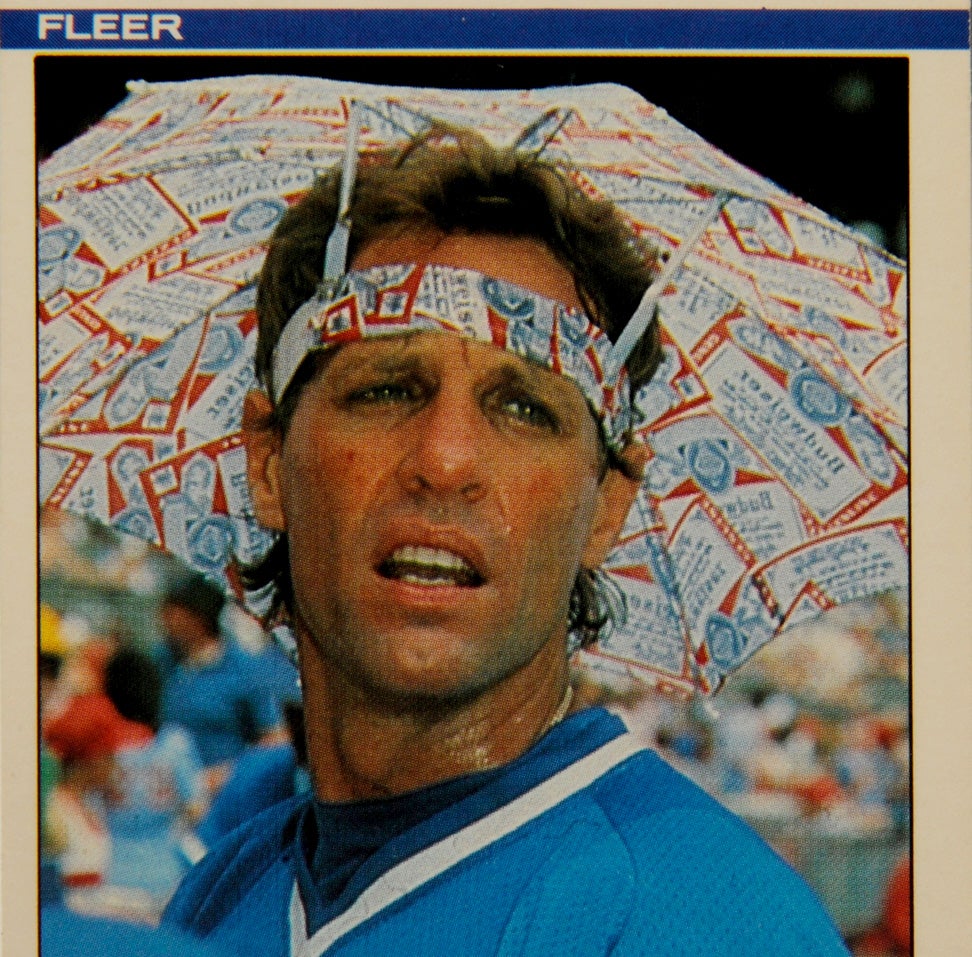

At first, Lyle stepped away from baseball completely. He did some work as a greeter at a casino and also made memorable appearances on TV pitching Miller Lite beer.

After a 16-year absence, Lyle finally returned to baseball. Given his habit of joking and pranking, it might come as a surprise that Lyle became a minor league manager, but he was a highly competitive player who yearned to compete in other ways. Lyle joined the Somerset Patriots, a team in the independent Atlantic League. As the skipper of the Patriots, Lyle led the team to Atlantic League titles in 2001, 2003, and 2005. Lyle then retired from managing in 2012.

Lyle never seemed consumed with the idea of managing in the major leagues, though I am sure he would not have turned down the opportunity if it had come up. And how much fun would that have been? Could you imagine the manager calling a team meeting and then emerging from a casket, in a vampire-like state, to address the troops?

For the first time ever, the major leagues might have had a manager who pulled more practical jokes than his players. And knowing Sparky Lyle, he would have loved every minute of it.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan

#CardCorner: 1987 Topps Mike Easler

#CardCorner: 1972 Topps Jose Pagan