The thing Al is most proud of is that in Vietnam, he never lost a man.

- Home

- Our Stories

- #CardCorner: 1982 Fleer Al Bumbry

#CardCorner: 1982 Fleer Al Bumbry

The 1982 Fleer set has never received its full due. Nor has Al Bumbry, ballplayer and war veteran. They both deserve more recognition.

Perhaps the lack of love for 1982 Fleer stems from the early struggles that both the Fleer and Donruss companies faced in the early 1980s. Having just won the right to produce full sets of cards, Donruss and Fleer rushed out sets in 1981, making some mistakes in content and accuracy along the way. The companies were also relatively new at making cards; Fleer last produced a set of baseball cards in the early 1960s, and those were limited sets featuring players like Ted Williams and Maury Wills. With very few of their creative staff members having much of a history of producing cards, it was inevitable that Fleer would go through some growing pains, just as Donruss did with its sets in the early 80s.

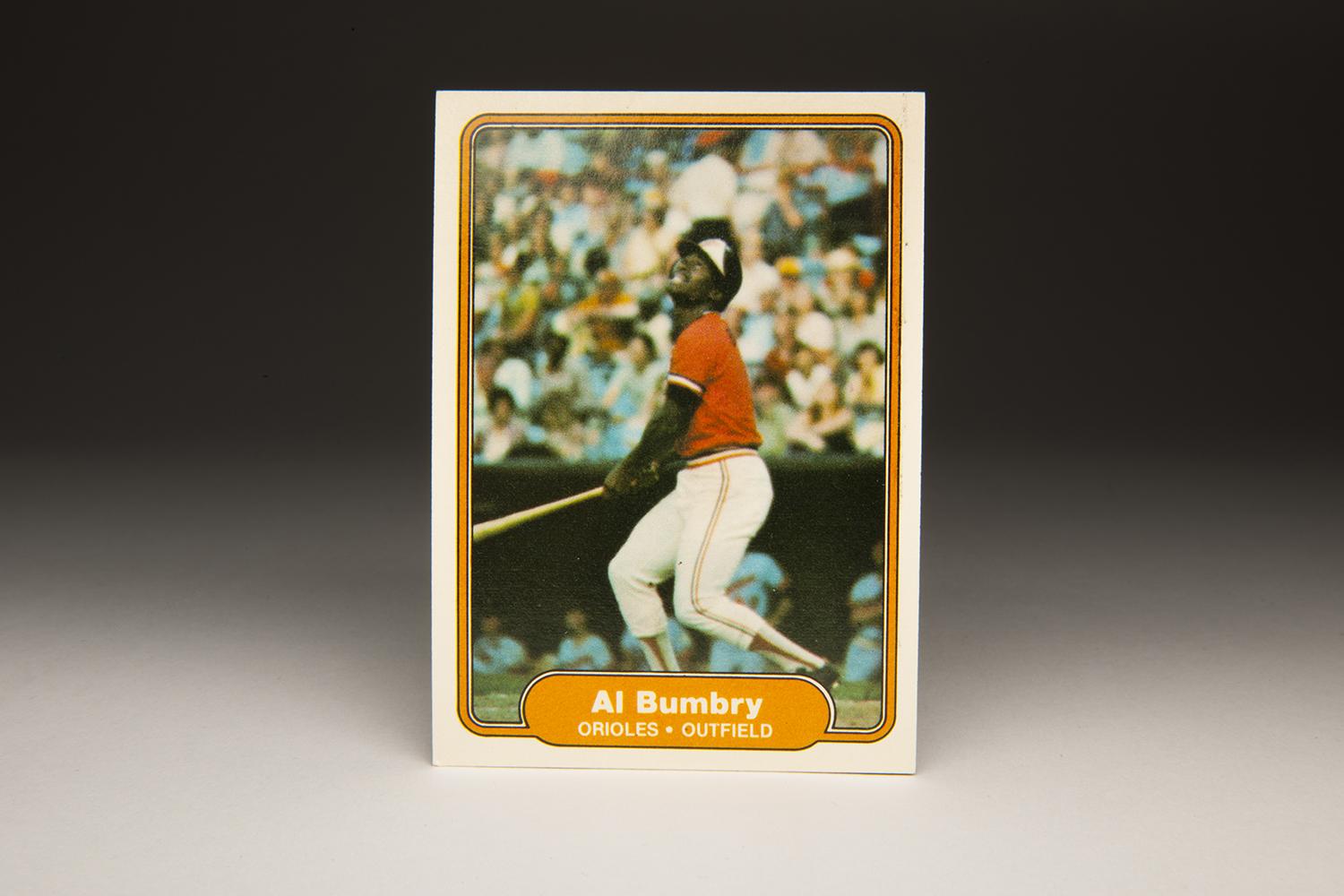

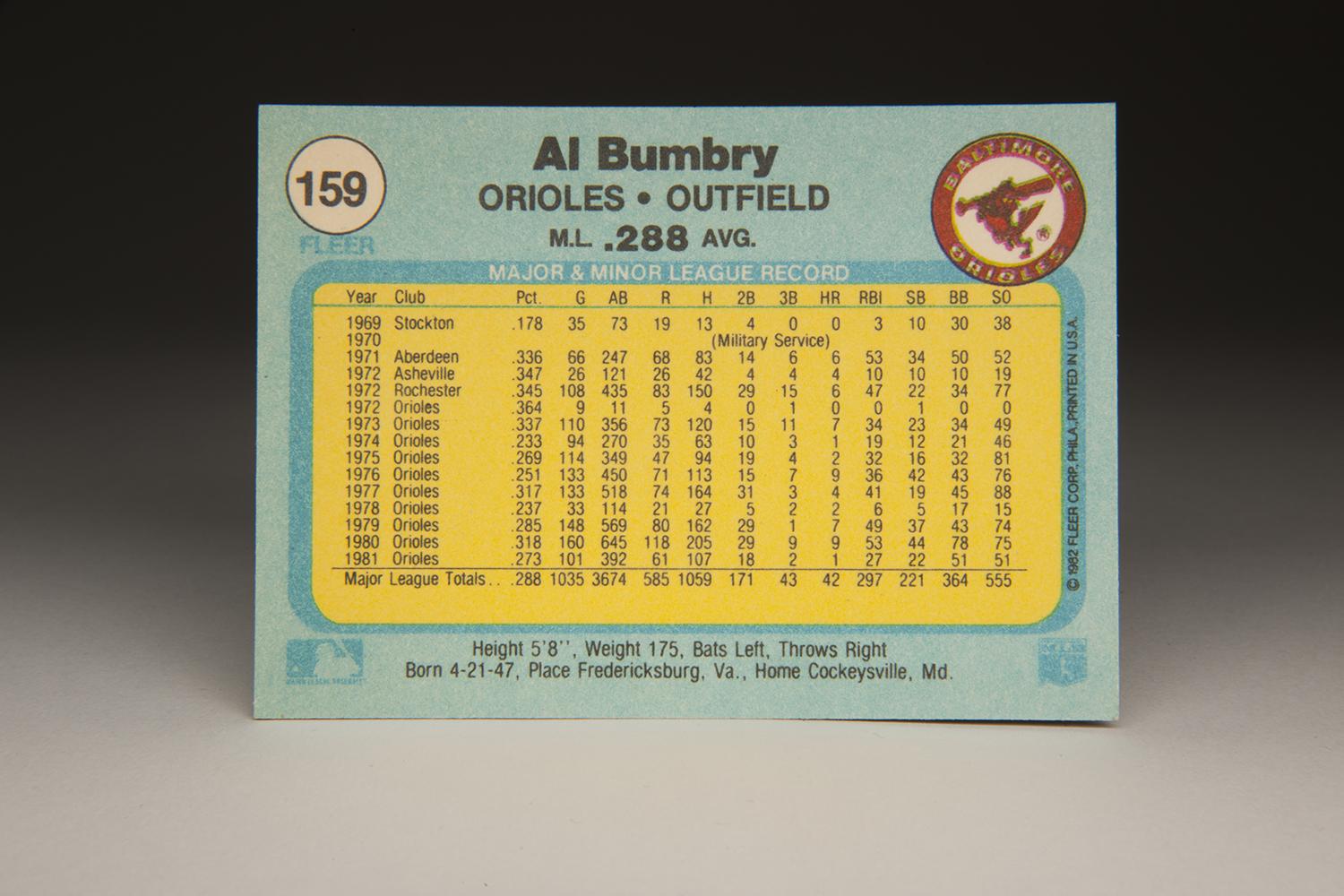

Yet, the 1982 Fleer set has always stood out as a quietly excellent set. First off, Fleer produced cards on thick stock, which helped them hold up better. The backs of the cards are presented in light colors, making it easier to read the statistical information and the accompanying biographies. Most importantly, the fronts of the cards feature such a basic, simple, minimalist design that it allows the photography to take up most of the physical space on the card. Other than a thin, framing line around the edges of the card, the only design is a small name plate at the bottom, shaped like a military dog tag. It gives us the player’s name, position, and team – and that’s it. It’s so simple as to be stunning.

Allowed to shine here, the photography in 1982 Fleer is generally well above average, with many more crisp shots than the occasional blurry one. There is a good mix of action, portrait, and posed photographs, so we never get tired of seeing the same kinds of cards over and over. Fleer used some creativity, too, by showing players in unusual poses or settings. The card of New York Mets pitcher Pete Falcone shows him sitting at his locker, a smile on his face as he holds up one of his own baseball cards. There is also a card of Montreal Expos infielder Brad Mills sitting in the dugout while blowing an enormous bubble, reminiscent of Kurt Bevacqua’s 1977 Topps card. Fleer gives us a card of Nolan Ryan throwing, not on an actual mound, but while warming up in an unknown bullpen.

In one of my favorite cards of all-time, we actually see a player, Dan Quisenberry, taking part in Spring Training calisthenics. I can’t ever remember seeing a player photographed in the middle of morning workouts the way that Fleer did with the late Quisenberry. It gave us a new definition of an “action” photograph.

Among the many action shots is an attractive card of Al Bumbry, the veteran outfielder for the Baltimore Orioles. On a sun-soaked day at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore, we see Bumbry wearing the Orioles’ alternate orange jersey, as opposed to their traditional home whites or road grays. Photographed moments after his swing, with the bat extended from his waist, Bumbry appears to have lofted a foul ball down the left field line. He is letting out a bit of a grimace, a sign that he missed a pitch he felt he should have smashed, while carefully watching the ball’s trajectory down the left field line. Clearly, this is not the result that Bumbry wanted, but he does show some good form here; his body looks balanced at the completion of his follow-through. The balance gives the card some artistry, as does the way that we see Bumbry transposed against the visiting players in the dugout and the fans who are packed into the box seats along the first base line.

It’s a memorable card for a player who deserves to be better remembered. As a student at Virginia State, a young Al Bumbry showed interest in becoming a high school teacher. He also became a star on the basketball team, but didn’t play baseball until his senior year.

Bumbry’s interest in teaching eventually lessened, while he became more passionate about baseball. In the summer of ’69, he was drafted by the Baltimore Orioles in the 11th round and assigned to Stockton, a Class A team in the California League. Bumbry knew that his time with Stockton would be brief. In attending Virginia State, he had paid for his tuition through an ROTC (Reserve Officers Training Corps) scholarship. As a result, he was committed to service in the U.S. Army. After only 35 games with Stockton, Bumbry made his way to a training facility and then to Vietnam. He would miss the rest of the 1969 season and all of 1970 while stationed near Saigon.

Of all the major leaguers to serve during the Vietnam War, Bumbry had one of the most distinguished tenures. As an infantry platoon leader stationed in the countryside near Saigon, he earned the Bronze Star for heroism before receiving his honorable discharge. None of Bumbry’s men lost their lives while under his leadership. As his longtime Orioles manager Earl Weaver said, “The thing Al is most proud of is that in Vietnam, he never lost a man.”

Even without direct casualties, Bumbry’s time in Vietnam left its scars. In 1978, his Orioles teammates planned a trip to a local theater to see The Deer Hunter, a critically acclaimed, Academy Award-winning film that starred Roberto DeNiro, Meryl Streep and the late John Cazale. The film was based on the Vietnam War, and more specifically the difficulties faced by three Pennsylvania steel workers who enlisted in the Army. The three men became prisoners of war, forced to participate in “games” of Russian roulette against one another.

A powerful film, The Deer Hunter would win Best Picture for 1978, but Bumbry wanted no part of seeing it. For him, the memories of serving in Vietnam were still too close, too scarring, for him to want to relive the experience in a theater. Understandably, Bumbry declined the offer from his teammates.

For most of his career, Bumbry talked little about his experiences in Vietnam. It was not until 1991 that he opened up publicly about his military duty during the war. “I’m proud I served in the Army,” Bumbry told sportswriter David Cataneo of the Boston Herald. “As far as being proud of being in a war, I can’t say I’m particularly proud of that. I don’t think anyone who goes to war is happy to go to war.”

Bumbry served 11 months in Vietnam, and while it had a lasting impact on him emotionally, it did not affect his considerable athletic skills. Returning to baseball in the middle of the 1971 season, Bumbry batted .336 for Aberdeen of the Northern League. Given his absence of a year and a half, Bumbry’s performance ranked as remarkable.

Bumbry continued to move up through the O’s chain in 1972, hitting .347 in the Double-A Southern League and batting .345 at Triple-A Rochester. He also earned the nickname “Bumblebee,” a tribute to the speed and quickness that the 5-foot-8 Bumbry showed on the basepaths. Having mastered the art of hitting and stealing bases at the minor league level, Bumbry was obviously ready for a late-season call-up in 1972. The O’s brought him to town in September and watched him collect four hits in 11 at-bats, rounding out a terrific season at three different levels.

With Don Baylor, Paul Blair, and Merv Rettenmund already established in the outfield, there was no room for Bumbry in Baltimore’s Opening Day starting lineup in 1973. But the Orioles made sure to include him on the roster, using him as a late-inning defensive caddy over the early weeks of the season. By May, Bumbry could be held back no more. He emerged as a platoon outfielder, seeing time in both left field and right field. Even though he played in only 110 games, he led the American League in triples, batted .337 and slugged .500, and won Rookie of the Year honors in a runaway. Bumbry teamed with Rich Coggins, another rookie speedster who batted .319, and veteran Don Baylor to give the Orioles the kind of basestealing capacity they had not previously possessed under Weaver.

Bumbry’s speed and hitting seemed likely to cement his status as the Orioles’ leadoff man, at least against right-handed pitching. Yet, Bumbry faced struggles. Like many former rookies, he did not hit as well as a sophomore. In 1974, his batting average fell off to .233 and he lost playing time to Coggins. He fared better in 1975 and ’76, eventually regaining a regular place in the lineup, but he failed to duplicate the numbers he had posted as a rookie.

In 1977, Bumbry flashed some of his rookie year talent by hitting .317 and winning the team’s center field job, becoming the fulltime successor to Paul Blair. Bumbry didn’t have much of a throwing arm, but his speed and range helped him become a capable defender in center field. Then came another bump. In May of 1978, Bumbry fractured and dislocated his ankle. The severe leg injury ruined his season, limiting him to 33 games and a .237 batting average.

His contract expired, Bumbry became a free agent, but teams showed limited interest in him because of concerns over his ankle. So he returned to the Orioles in 1979, signing a three-year contract. Bumbry’s rollercoaster ride continued, but this time on the upward swing. Working hard to make a comeback from the ankle dislocation, Bumbry hit .285 with 37 stolen bases, emerging as a key player on a pennant-winning team. The lone true basestealing threat on an Orioles club loaded with power, Bumbry advanced to the World Series for the first time in his career.

In 1980, Bumbry put together his best season since his rookie campaign. Appearing in a career-high 160 games, he batted .318 with 78 walks and 44 stolen bases. For the first time in his career, he made the All-Star team and also earned some votes in the MVP balloting.

Bumbry would never again put up such numbers, but he remained an effective platoon player for most of the next four seasons, making his second World Series appearance in 1983. This time the Orioles won it all, allowing Bumbry to claim his first World Series ring.

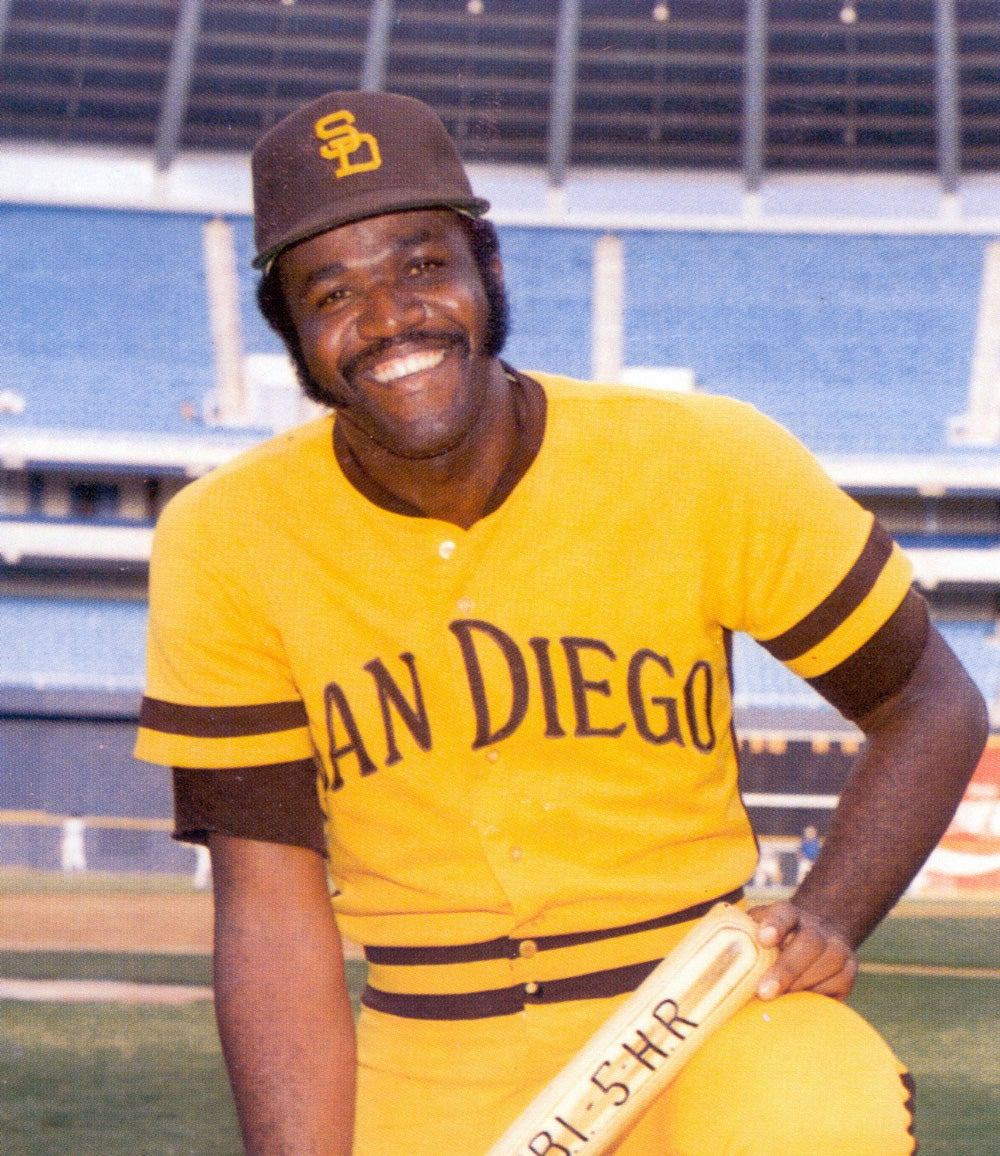

The following year, Bumbry lost the center field job to young John “T-Bone” Shelby. With Shelby representing the future, Bumbry left the Orioles as a free agent and signed a contract with the San Diego Padres, the defending National League champions. Employed as a backup outfielder, he struggled with the Padres and called it quits after the 1985 season.

After a two-year separation from the game, Bumbry became a coach, first with the Boston Red Sox and then the Cleveland Indians. He later joined the staff of the Colorado Silver Bullets, the women’s teams of 1990s vintage. It was during his Red Sox coaching tenure that I became reacquainted with Bumbry. It happened at the 1989 Hall of Fame Game, scheduled to take place in Cooperstown between the Red Sox and the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds ran into problems with their connecting flight in Montreal and couldn’t make it to Cooperstown in time for the 2 p.m. start. So the Red Sox improvised, putting on an intrasquad game between two teams, the “Red Sox” and the “Yaz Sox.” Needing players to fill out the two rosters, Bumbry agreed to suit up and play. He looked fit, just as he had during his days in Baltimore, and played well in the exhibition game at Doubleday Field.

Of course, for a guy who endured the horrors of Vietnam, I imagine that suiting up to play a ballgame a few years after retirement was a relatively easy task. After all, this was a man who saw his sergeant killed during the war, a man who saw things that most of us cannot fully comprehend, unless we have been in battle ourselves. For a true hero like Al Bumbry, playing ball, as difficult as that can be at the major league level, must have been the easy part.

Bruce Markusen is the manager of digital and outreach learning at the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Related Stories

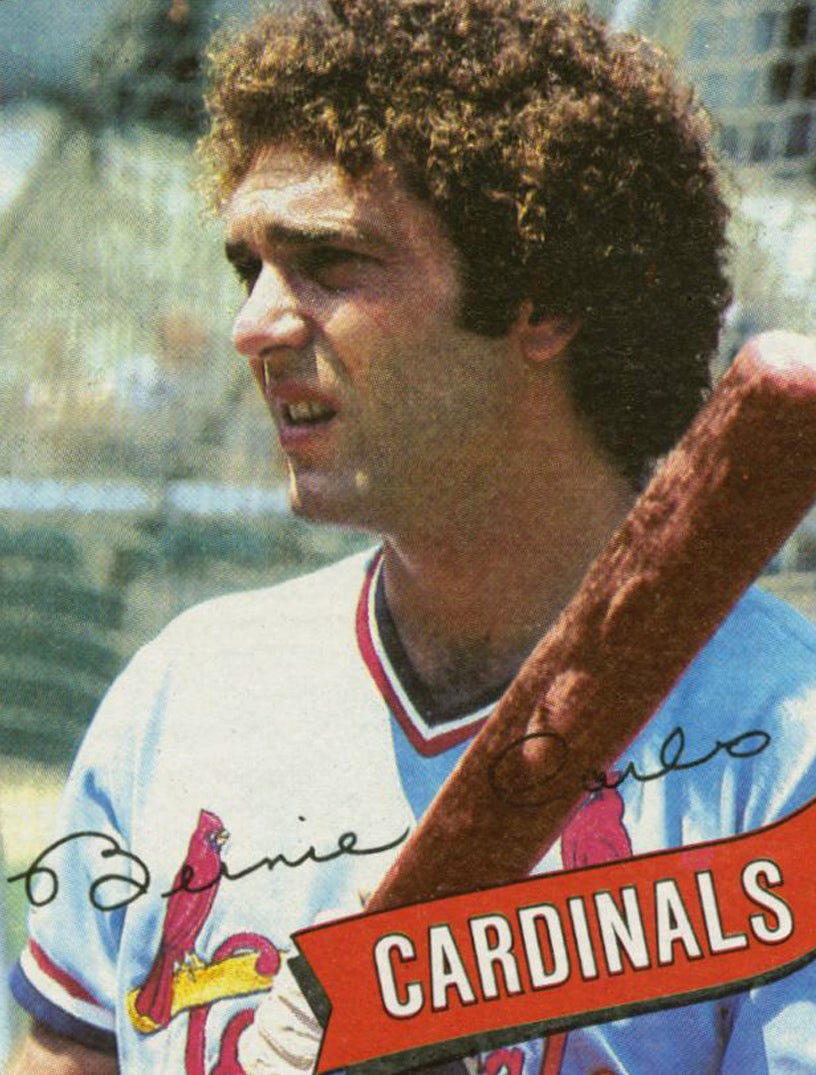

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

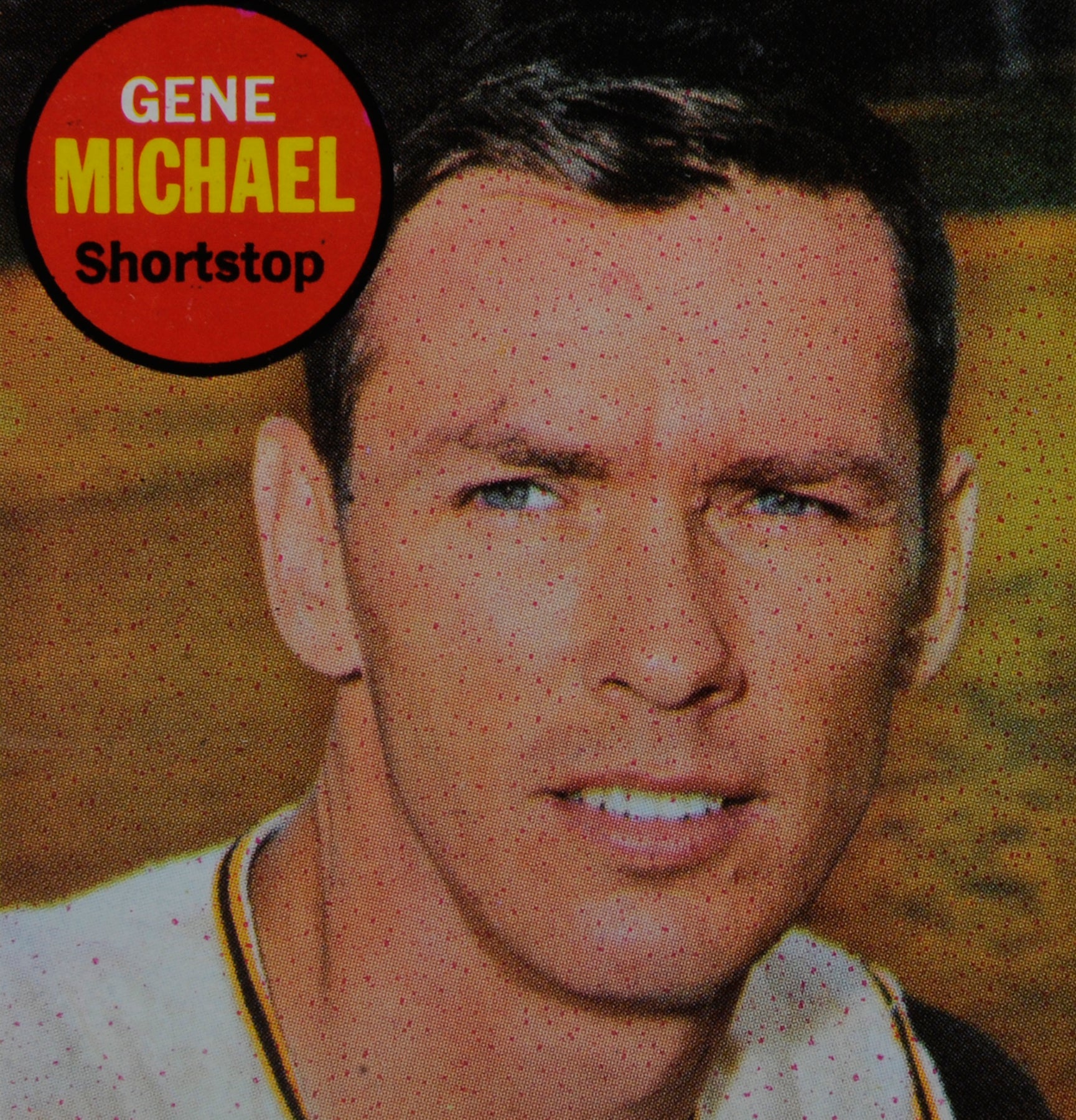

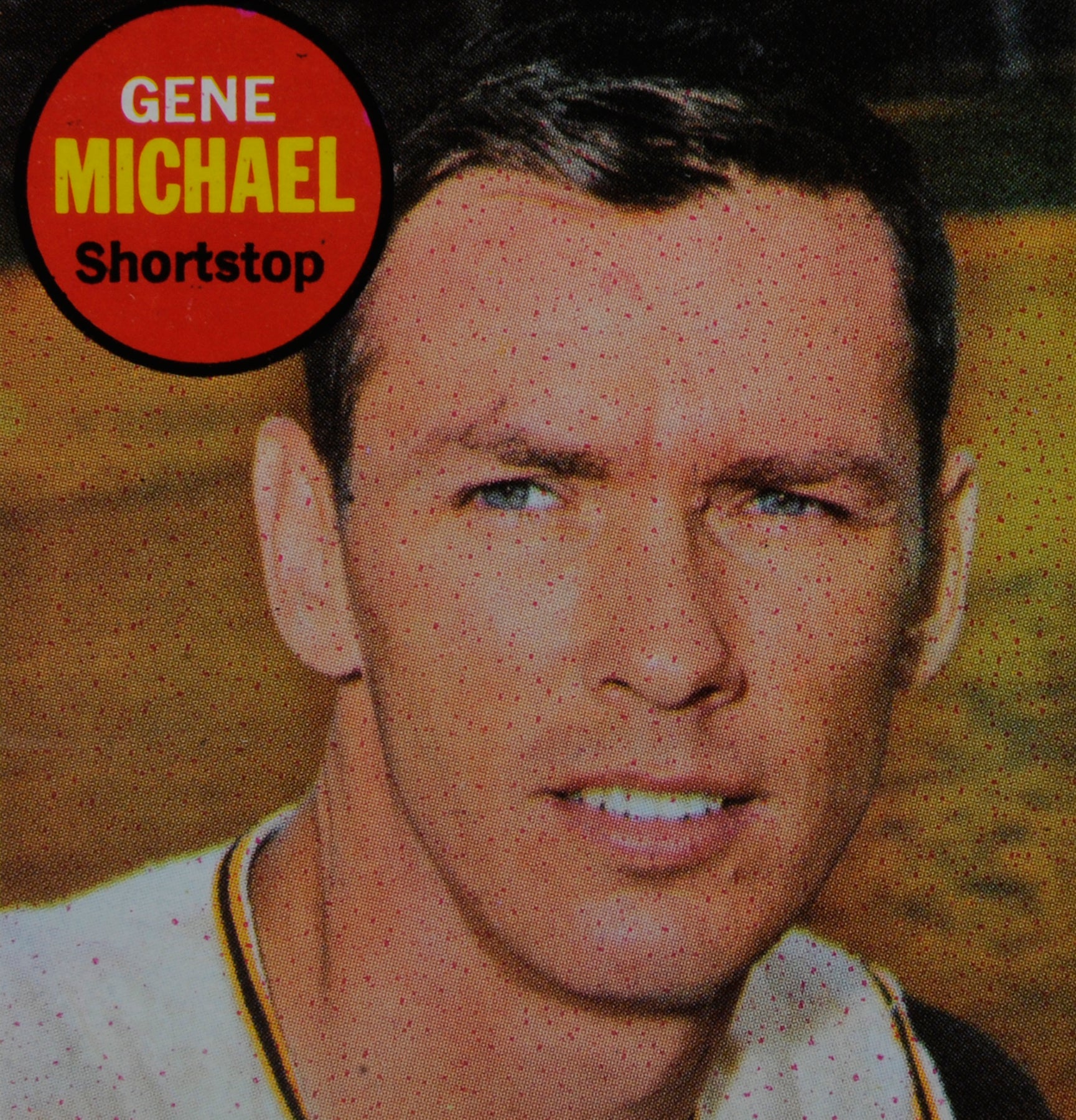

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

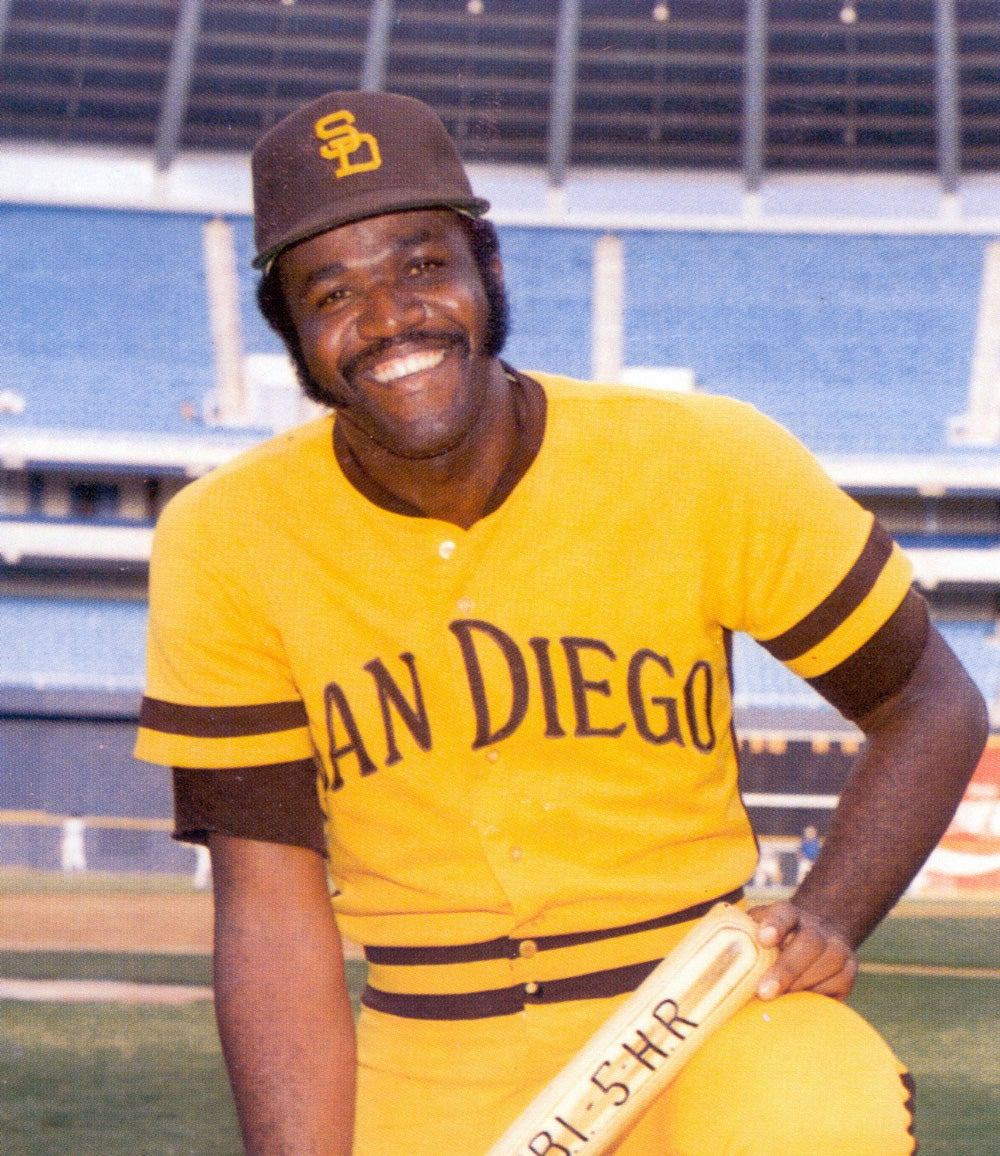

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert

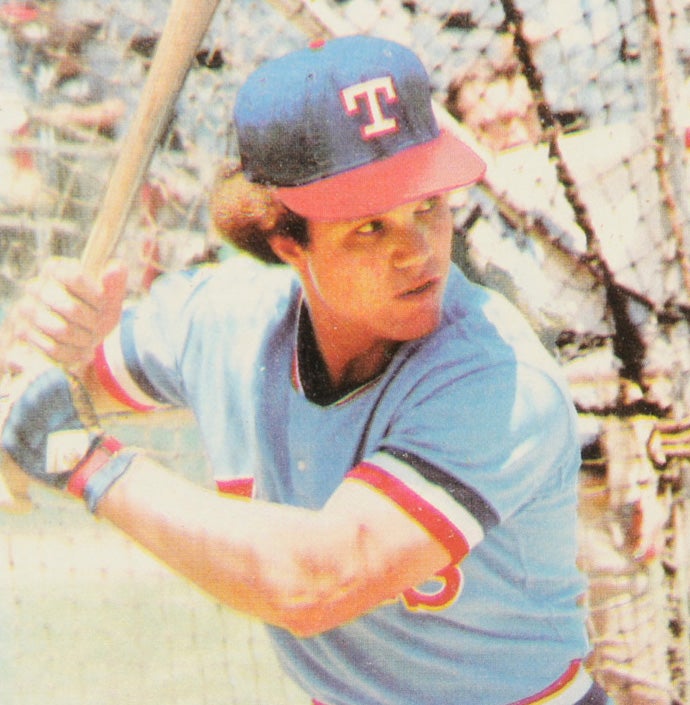

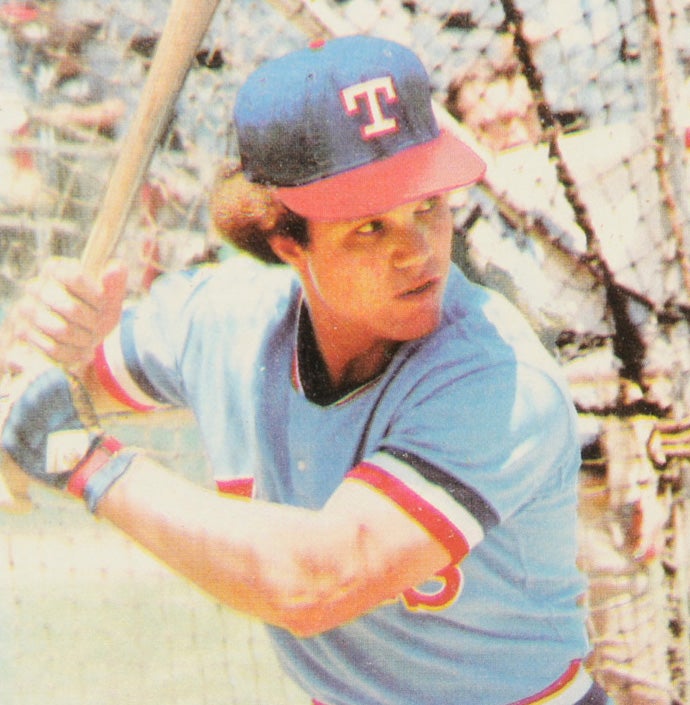

#CardCorner: 1979 Topps Bump Wills

#CardCorner: 1980 Topps Bernie Carbo

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Gene Michael

#CardCorner: 1969 Topps Nate Colbert